Bold, defiant, yet direct, without the depth that the important and complex issue that Jordanian director Amjad al-Rasheed chose to venture into in his first feature film, deserves. The film "Inshallah A Boy", or "Inshallah Walad", which delivers a critique of Jordan’s structural oppression of women and girls, is competing in the Critics' Week section of the 76th Cannes Film Festival (May 16-27, 2023).

This marks the first-ever participation of Jordanian cinema in the prestigious festival, with a film that addresses several issues including women's rights to inheritance and custody of children. It also crosses red lines that Arab society forbids discussing, such as the headscarf, extramarital sex, maternal instincts, abortion rights, divorce among Christians, and other issues that we could not have imagined would be directly addressed in an Arab film. Thus, "Inshallah A Boy" came as a surprise to the festival audience.

From the opening scene, young director Amjad al-Rasheed chooses to be direct and quite urgent in presenting multiple intertwined situations, whether meticulously detailed or deliberately compressed, with a tone of elevated dialogue and impassioned performances.

Bold, defiant, yet direct and without the depth that such an important and complex issue deserves, Jordanian director Amjad al-Rasheed's first feature film, "Inshallah A Boy", delves into heavy themes such as Jordan’s structural oppression of women and girls

The film, which the director co-wrote with Mona Nasser and Delphine Augte – perhaps adopting a direct approach to easily reach the audience – begins with a tense wife trying to reach a bra that has fallen onto her neighbor's laundry lines below. She fumbles with it and it then falls onto the street, and she leaves it there for passersby in embarrassment, as if it were a disgrace that must be evaded!

She gazes at her own reflection in the broken bathroom mirror, and her image seems incomplete, just like it is perceived by society. She enters the bedroom exhausted, then quickly dolls herself up, and approaches her husband on the bed. Her indifferent husband barely notices her, appearing cold and emotionless, turning his back under the pretext of being exhausted. Disheartened, she falls asleep feeling frustrated, and the day ends.

With the arrival of a new morning, the film's events begin to unfold. The wife is active inside the house, preparing what her daughter needs to go to school, and calling for her husband but receiving no response. Quietly, we realize that he has died, and so the tragedy begins.

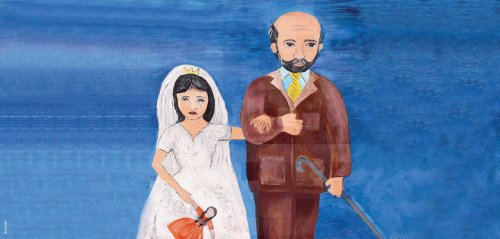

In the funeral, the voice of a woman wearing the niqab rises above the voice of the Quran, urging the wife – now a dazed, grieving widow – not to leave the house during the Iddah (waiting period for women following death of a husband or divorce). Everyone disperses, leaving her to face life alone. She returns to her job in the house of a Christian family, caring for an elderly woman with Alzheimer's. In the first appearance of her husband's brother, her brother-in-law demands that she must repay a debt of her husband's that she was never informed about. She objects, asking how can she come up with the money to repay the debt when he left her with nothing, and all the money she makes is spent on the house? He gets angry and asks her to sell the house so he can take his share (half of the inheritance) and use it to repay half of the debt, despite knowing that she had contributed her own money and all her jewelry to this small house, the only shelter for her and her daughter.

The film crosses red lines that Arab society forbids discussing, such as the hijab, women's rights to inheritance, extramarital sex, abortion, divorce among Christians, and other issues that we couldn't imagine would be directly addressed in an Arab film

In Islamic countries, particularly among Sunni Muslims, the inheritance law based on Islamic Sharia is applied in accordance with the interpretation of scholars of verses in the Quran addressing inheritance. The interpretations differ between the Shia and Sunni scholars. While a daughter can withhold the entire inheritance from others among the Shia, according to the Sunnis, an only daughter can only inherit half of the estate or inheritance, and the other half goes to her father's relatives who are not obliged by law to support her, pay for her education, or cover her marriage expenses and so on. Sometimes, she may not even see them again after the distribution of the inheritance, and society is filled with shocking and painful stories of girls who have lost financial security after the death of their father, and they may be thrown onto the streets mercilessly after they had been living in the comfort of their inherited wealth, and were betrayed by her own relatives.

From the beginning, and at a fast pace, the film puts us in front of a law according to which the uncle insists on selling the only residence that shelters his niece and his widowed sister-in-law, Nawal, in order to divide the inheritance "legally and according to religious law". He doesn't care about Nawal's fear and distress, and neither he nor her negative brother answer her legitimate questions... Where will she go with her daughter? And if she had a son, would he have the right to evict them from the house?

The film shocks the viewer with questions that have no humane answers, in a time that has undergone many changes without a corresponding change in mentalities to suit the logic of life nowadays, and not in the prophetic era.

Interestingly enough, the young director's film is devoid of any positive male model; as all the male characters in it are negative and have twisted mentalities, driven by greed and lust

The brother-in-law corners her, pressuring her to settle the debt, and during this time, another issue erupts when Lauren, the daughter of the bourgeois family for whom Nawal works, discovers that she is pregnant. Lauren, who does not want this pregnancy from her unfaithful husband, doesn't want to become a mother at all. She doesn't feel that motherly instinct (and this is another issue that many fear approaching, as not all women – as we were taught before – possess the instinct of motherhood).

Nawal naively asks Lauren, "Then why did you get married?" to which the other simply responds, "For sex". Nawal doesn't dwell on the response for long because, to her and others like her, these sensations have become an unattainable luxury. However, she gets an idea from the current predicament: Why not pretend to be "pregnant" and thus halt the distribution of her daughter's inheritance until she supposedly gives birth to her child? Who knows, maybe it will be a male child, securing her position and guaranteeing her home! Thus, Nawal needs a male to confront the oppression of her unjust, male-dominated society. She stands in solidarity with Lauren and tries to help her with the abortion, but she fails and loses her job with the family who punishes her for this action.

The film explodes like gunpowder, fueling the events with a momentum of important topics and themes that quickly unfold, reaching the depth they deserve. It continues to boldly address what some consider taboo, and the talented director is credited for his support of women against the gender discrimination that continues to mercilessly be practiced upon them.

What's strange is that the young director's film is devoid of any positive male model; as all the male characters in it are negative and have twisted mentalities, driven by greed and lust: the brother-in-law, the brother, the Christian husband, the work colleague, even the doctor. However, the director defends his male characters, saying, "They are not negative or psychologically twisted. Circumstances have placed them in situations that force them to act this way, and I see their behavior as a normal reaction given the difficult events and their harsh financial conditions, as well as the laws that grant them rights, which they then act upon."

Two years ago, I watched the Jordanian film "Daughters of Abdul-Rahman", directed by Zaid Abu Hamdan. Both films revolve around the suffering of women in Arab societies, and their directors are men. However, there is no single positive male figure in either film, except for the old, sick father who left and never came back! It is astonishing that the film also belongs to the loud and theatrical performance style, and this direct, loud approach seems to be a characteristic of Jordanian cinema, which is now taking significant and promising strides, and gaining noticeable presence in international festivals after decades of being limited to local screenings.

The Jordanian film critic, Najeh Hassan, documents in his book "Jordanian Cinema... Spectra and Dreams" the beginning of cinema in his country with the film, "Sera' fi Jerash" (Struggle in Jerash) in 1957. The film "Theeb", directed by Naji Abu Nowar in 2014, won the Best Director Award at the 71st Venice Film Festival and is considered by Najeh Hassan a significant milestone in Jordanian cinema history. After that, a generation of young directors has presented a number of ambitious films.

The film explodes like gunpowder in the conservative society, and boldly addresses what some consider taboo, and the talented director is credited for his support of women against the gender discrimination that continues to mercilessly be practiced upon them

Perhaps the most important contribution of Jordanian cinema in recent years, in my opinion, is the film "Farha" by Darin Sallam. The film represented Jordan in the competition for the Best Foreign Language Film category at the 2022 Academy Awards. It demonstrated a high level of maturity and depth, even though it did not have much luck in representing Jordanian cinema in international festivals compared to "Daughters of Abdul-Rahman", which toured Arab and foreign festivals.

The film "Inshallah A Boy" stars Mouna Hawa, Haitham Omari, Yumna Marwan, Mohammad Al Jizawi, and Eslam al-Awadi. It was filmed last year in the Jordanian capital after receiving production funding from the Jordan Film Fund, under the Royal Film Commission – Jordan (RFC). The film received a great reception after its screening at the current Cannes Film Festival. But I was surprised by the cautious statements made by the director to Variety Magazine, where he said, “I can’t predict people’s reactions, but I am going to be honest: there are already plenty of negative comments out there. I don’t know why, but there is this feeling that we, Jordanians, don’t make good films – even when they go to Cannes. Or that they are too scandalous”, noting that at the end of the day, he just wants to open a conversation.

However, director Amjad al-Rasheed confirmed in a brief interview with me that these statements were made days before the screening and he believes that his words were misunderstood.

The talented director, known for his progressive thinking, affirms that he did not encounter any problems or censorship obstacles regarding this bold scenario. Instead, he found unlimited support from the Royal Film Commission – Jordan (RFC).

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!

Join the Conversation

ماجد حسن -

16 hours agoيقول إيريك فروم: الحبُّ فعلٌ من أفعال الإيمان، فمن كان قليلَ الإيمان، كان أيضًا قليل الحب..

Toge Mahran -

1 week agoاكتر مقال حبيته وأثر فيا جدا♥️

Tayma Shrit -

1 week agoكوميديا سوداء تليق بمكانة ذاك المجرم، شكرا على هذا الخيال!

Europe in Arabic-Tarek Saad أوروبا بالعربي -

1 week agoالمقال بيلقى الضوء على ظاهرة موجوده فعلا فى مصر ولكن اختلط الامر عليك فى تعريف الفرق بين...

Anonymous user -

1 week agoاحمد الفخرناني من الناس المحترمة و اللي بتفهم و للاسف عرفته متاخر بسبب تضييق الدولة علي اي حد بيفهم

Europe in Arabic-Tarek Saad أوروبا بالعربي -

1 week agoمقال رائع..