We try to console ourselves by saying, "God will compensate," but the issue for us is that this is far more than just a pile of “rubble.” This is an existential struggle. Amid the shock and pain we endure, we are well aware that every stone and every brick carries a memory, a story, and a history of thoughts, traditions, customs, and moments—of family gatherings, conversations with neighbors, and the clinking of tea cups. They are castles that dazzled us with their beauty and ancient architecture, historical homes resembling an elderly person we wish we could meet and embrace one day. They are rocks and stones that have memorized our first steps, marked vibrant marketplaces we visited during holidays, and served as guardians of childhood memories. We grew up fearing they would change, lest we lose the memories of our childhood with them—the gatherings of everyone we knew.

What does it mean to watch our villages, markets, and neighborhoods be obliterated? It means an entire lifetime shattering into fragments and dust along with our homes. It means seeing all those images in our minds—the childhood friends, the neighbors, the image of my grandfather heading to the Nabatieh market—disintegrate. It is a pain no less than the agony of childbirth, a torment that no words can fully convey and no expressions can ease. With every burned oak and olive tree, with every destroyed stone, a lifetime is torn from the depths of our being, and a piece of our identity is stripped away as if skin were being peeled off, severing us from our ancestors and our land.

"In times of war, it’s not just the people that are killed—spaces are killed too. When we hear terms like ‘scorched earth,’ it means the erasure of all memory, time, and history. These practices do not only involve erasing physical landmarks but also destroying the collective memory of future generations."

Throughout its repeated assaults on Lebanon, Israel systematically sought to obliterate our memory and erase our identity, hoping to extinguish an entire history. The targeting of cultural, religious, and historical sites is not merely a material loss; it is an assault on the collective memory that shapes the identity of a people and their connection to their homeland and their past. How can an entire society resist the loss of its identity and history after the annihilation of the places that form its memory? And how can it adapt after being uprooted from its land and its collective memory wiped out?

Fears of our identity and memory being wiped out

In a conversation with Raseef22, sociologist Dr. May Maroun asserted that a human being is a complex network of transferred and obtained histories and memories.

During wars, when a spatial genocide occurs, individuals face a harsh equation, as the loss of land is deeply tied to the loss of a significant part of their identity. Dr. Maroun points out that when a person is uprooted from their place, a part of their self and identity is uprooted as well. This, she explains, is why the impact of wars and conflicts transcends generations, leaving deep scars in the collective memory of individuals, communities, and societies.

A man stands next to the rubble of his destroyed home in Haret Hreik in the southern suburbs of Beirut

A man stands next to the rubble of his destroyed home in Haret Hreik in the southern suburbs of Beirut

A man stands next to the rubble of his destroyed home in Haret Hreik in the southern suburbs of Beirut

Through its repeated assaults on Lebanon, Israel systematically seeks to obliterate our memory and erase our identity, aiming to extinguish an entire history. The destruction targeting cultural, religious, and historical sites is not merely a material loss; it is an assault on the collective memory that shapes the identity of a people and their connection to their past and homeland. How can an entire society resist the loss of its identity and history after the annihilation of the places that form its memory? And how can it adapt after being uprooted from its land and its collective memory wiped out?

In times of war, Maroun notes, it’s not just the people who are killed—spaces are killed too.

“When we hear terms like ‘scorched earth,’ it means the erasure of all memory, time, and history. These practices do not only involve erasing physical landmarks but also destroying the collective memory of future generations,” she said, drawing from her personal experience of displacement from eastern Saida in 1985. “I lost all the memories that connected me to that area—from ‘al-Ain’ (the spring), the hills, and the olive trees, to my school and my grandfather’s house. Even when people returned to those areas and rebuilt them, the places never regained their old spirit,” she explains.

Maroun notes that peoples who have lost their land often resist the erasure of memory by preserving their heritage and language, clinging tightly to their identity, even in the diaspora.

“Take the Armenians who were subjected to genocide in 1915—they continue to cling to their identity, rebuild their memories, maintain their language, and pass it on to future generations,” Dr. Maroun said. Speaking on whether modern technology and the presence of images can ease the pain of loss, Maroun clarifies that memories tied to war and displacement go beyond static images and visuals. They carry with them a deep sorrow that reflects suffering and loss. She references Mohammed Abi Samra’s book “Inhabitants of the Pictures,” which illustrates how tragic and traumatic memories become an integral part of both personal and collective identity, and prove difficult to recover or relive, especially when the past is steeped in loss and displacement.

Between white phosphorus and bombardment: Destroying heritage and fragmenting collective memory

Architect and researcher Abir Saksouk informed Raseef22 that “spatial genocide” in the local context refers to the systematic and deliberate destruction of areas through “premeditated” violence and prior intention. This includes the targeted and systematic obliteration of all types of environments, whether natural, cultural, or urban.

What does it mean to watch our villages, markets, and neighborhoods be obliterated? It means an entire lifetime shattering into fragments and dust along with our homes. It means seeing all those memories in our minds disintegrate. With every burned oak and olive tree, with every destroyed stone, a lifetime is torn from the depths of our being and a piece of our identity is stripped away, severing us from our ancestors and our land.

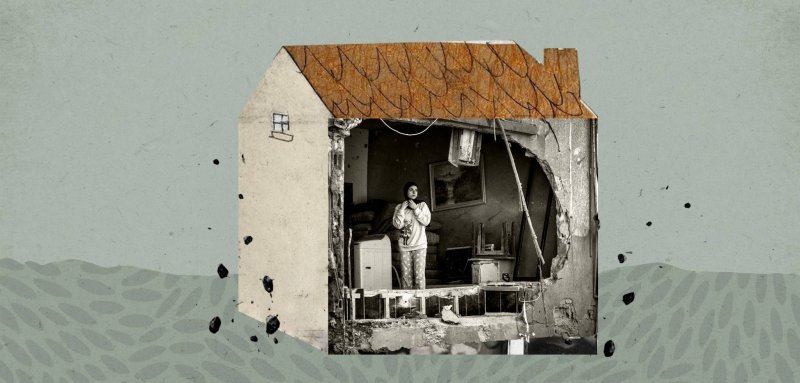

A girl looks out from a hole in the side of her home in Saida, Lebanon

A girl looks out from a hole in the side of her home in Saida, Lebanon

A girl looks out from a hole in the side of her home in Saida, Lebanon

Saksouk highlighted that spatial genocide, or “the killing of a city,” always plays a crucial role in wars. It is "part of destroying collective memory and belonging. The aim is not only to demolish and erase buildings but to obliterate both individual and collective memories. It also erases historical spatial narratives and recollections."

“This is evident in the Lebanese context," she explains, adding that the goal is not only displacement and killing but also preventing the revival and restoration of life in these areas.

Saksouk also discussed the attacks on Lebanon’s border villages between October 2023 and February 2024, which were often subjected to intense bombardment by Israel. She explains that white phosphorus strikes and incendiary shells were among the primary tools used to destroy the rural environment.

According to Saksouk, the phosphorus shelling targeted several southern villages, including Kfarkela, Ayta al-Shaab, and Khiam, leaving long-term and severe impacts on the land and agriculture. This reflects Israel's deliberate effort to destroy the foundations of life in these areas. She emphasizes that the intensity of bombardments, especially starting from September 23, targeted areas like Dahieh, which Israel claims are strategic and precise strikes. However, when examining warning maps, it becomes evident that these strikes represent clear spatial genocide and eradication due to their density.

“Let us not forget that no matter how Israel tries to justify these strikes as targeting Hezbollah-controlled neighborhoods, Dahieh is part of the city, an integral component of its economic and social fabric, and a bustling hub of activity and life—it is Beirut.”

“Spatial genocide, or the killing of a city, always plays a crucial role in wars. It is part of destroying collective memory and belonging. The aim is not merely to demolish and erase buildings but to obliterate both individual and collective memories. It also seeks to erase historical spatial narratives and recollections. This is evident in the Lebanese context.”

Saksouk clarifies that between the heavy phosphorus strikes in the South and the recent demolitions of massive areas and villages as a tactic, "we see Israel working to annihilate an entire geographic area, including its architectural infrastructure and social, cultural, and historical landmarks."

Smoke rises from the ruins of destroyed homes following an Israeli airstrike on the town of Nabatieh in South Lebanon.

Smoke rises from the ruins of destroyed homes following an Israeli airstrike on the town of Nabatieh in South Lebanon.

Smoke rises from the ruins of destroyed homes following an Israeli airstrike on the town of Nabatieh in South Lebanon.

Public Works Studio documented 11 villages where Israel employed the complete demolition of neighborhoods and villages, based on videos shared by Israeli soldiers and others. Saksouk stresses that cultural sites are not merely specific buildings but part of an integrated historical, social, and cultural fabric.

"When we talk about 11 villages documented as almost completely destroyed, it’s not just about demolishing structures but about erasing the cultural history of those areas," she explains. This includes “traveling and street markets, which are a key element of the South’s cultural heritage, such as public square markets that sustain the local economy and create social connections between villagers.” She listed popular markets in many southern regions, including Nabatieh, Hasbaya, Haris, Maarakeh, Khiam, and Odaisseh, all of which are integral to the local social and economic life.

Who holds Israel accountable?

A recent report, “Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Lebanon Due to Ongoing War,” by the Heritage Education Program and Heritage for Peace documents damage to historical landmarks in Beirut, the Bekaa, and the South caused by Israeli aggression. The report underscores the cultural and historical significance of these sites and explores the repercussions of their destruction on the environment, tourism, and the economy. Meanwhile, Public Works Studio mapped the impact of the war on Lebanese lands and people through maps entitled “What Can Be Read from Mapping Israeli Aggression on Lebanon?” The project aims to challenge dominant narratives and deepen the connection between land, geography, and people.

Saksouk also points out that over 6,000 buildings were destroyed in 25 border towns between October 2023 and late October 2024. She explains that the destruction is not restricted to homes and residential apartments but extends to natural environments and economic systems, emphasizing that these operations aim to erase the collective memory of the Lebanese people.

The Hague Convention and its Protocols of 1954 and 1999, which Lebanon has signed, emphasizes the protection of cultural and historical sites during armed conflicts. Legal expert Professor Hassan Jouni told Raseef22 that international law prohibits the destruction of cultural property due to its importance in the life of peoples. He points out that the first protocol of the Geneva Conventions prohibits targeting antiquities, monuments, and cultural property, stating that "even though Israel has not signed it, customary international humanitarian law and rules issued by the International Committee of the Red Cross still apply and are binding."

Dr. Maroun points out that when somebody is uprooted from their home, a part of their self and identity is uprooted as well. This, she explains, is why the impact of wars and conflicts transcends generations, leaving deep scars in the collective memory of individuals, communities, and societies. She highlights the profound implications of the spatial genocide that Israel is practicing in Lebanon, or what it means for a Lebanese person to witness the destruction of their villages, markets, and neighborhoods.

"Targeting these places constitutes a crime under international law and an indiscriminate attack prohibited by the Geneva Conventions, and erases the memory of people and deprive them of their right to life," emphasizing that this destruction goes beyond the military dimension and includes political objectives aimed at preventing the return of Lebanese citizens to their villages, thus facilitating the return of Israeli settlers to the north.

As for legal accountability, Jouni remarked that prosecuting Israel in an international court faces legal challenges, particularly with Lebanon’s recognition of Israel. Article 34 of the court's statute stipulates that only states can appear before it, meaning that Lebanon filing a lawsuit against Israel could be seen as an acknowledgment and recognition of Israel.

"For this reason, I don’t think Lebanon will pursue this route to avoid recognizing Israel," he added. Jouni also mentions the possibility of prosecuting Israeli officials in European courts but warns of complications related to sovereignty and immunity, given the political and legal challenges involved.

According to a statement by Mohamed Chamseddine, a researcher at Information International, the number of destroyed homes in southern Lebanon has reached 44,000, with an additional 120,000 homes having been partially damaged. He confirmed that the estimated cost to rebuild one house is $75,000, meaning the total cost for rebuilding these homes could amount to approximately $4.2 billion.

Challenges of reconstruction

There is no doubt that the imperial conflict plays a pivotal role in the suffering we are experiencing today. Countries suffering from imperial collapse and bankruptcy find no means of filling the void except through plundering and looting cultural heritage. An example of this is what the United States did during its invasion of Iraq, or what terrorist organizations, such as ISIS in Syria, destroyed to erase the footprint of antiquities. These acts are part of broader colonial and settler policies aiming to maintain the dominance of major powers.

In the context of settler colonialism, as seen in Palestine, the killing and cultural erasure of memory intersects with genocide, where Israel seeks to erase physical spaces and cultural symbols representing Palestinian memory, identity, and steadfastness.

Lebanon faces similar threats, with ongoing Israeli attacks on cultural and historical sites, from villages and heritage buildings to cemeteries and sacred sites. This systematic destruction not only targets physical structures but seeks to undermine the fabric of Lebanese history and attack Lebanese identity, contributing to a broad strategy aimed at weakening the community’s sense of belonging and continuity.

Israel's bombardment of the historic city of Tyre in South Lebanon

Israel's bombardment of the historic city of Tyre in South Lebanon

Israel's bombardment of the historic city of Tyre in South Lebanon

According to a statement by Mohamed Chamseddine, a researcher at Information International, the number of destroyed homes in southern Lebanon has reached 44,000, with an additional 120,000 homes having been partially damaged. He confirmed that the estimated cost to rebuild one house is $75,000, meaning the total cost for rebuilding these homes could amount to approximately $4.2 billion.

When examining warning maps, it becomes evident that Israel's strikes represent clear spatial genocide and eradication due to their density. “Let us not forget that no matter how Israel tries to justify its strikes as targeting Hezbollah-controlled neighborhoods, Dahieh is part of the city, an integral component of its economic and social fabric, and a bustling hub of activity and life—it is Beirut.”

Faced with these staggering numbers, alongside the threats of displacement and "spatial genocide," and the risk of disorganization in restoration and reconstruction efforts, Saksouk believes that rebuilding cannot follow traditional methods, as the current situation is far from "ordinary." Israel is employing new tools in its campaign of "spatial genocide," from violent and intense bombardment to the use of phosphorus weapons, which demands a fundamental rethinking of the tools and strategies of resistance. Saksouk poses a critical question: How can we build the future in the wake of spatial genocide and destruction?

The answer, she contends, does not lie in traditional reconstruction methods based on external funding or simply rebuilding “stone” and physical structures. Instead, it requires adopting a process of reconstruction grounded in the concept of "comprehensive recovery," which encompasses environmental, economic, social, and cultural dimensions.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!