In a modest home in the village of Al Bitran (southern Iraq), Zainab Raed, 12, sits crouched with her amputated right leg, which her family has fitted with a plastic bottle because they could not afford a prosthetic limb.

“Zainab was injured in a landmine explosion while on her way to school in 2024. She lost her eyesight and her right leg as a result,” her 62-year-old father told Raseef22.

What pains Zainab and her family the most is that she loved school and studying, yet she is now unable to continue her education or leave home on her own. Her dreams collapsed when she lost her leg and sight in the explosion, which her father blamed on “government negligence.”

Zainab’s father speaking about her suffering

Many Iraqis are subject to the same fate because of landmines and war remnants, a problem successive governments have failed to resolve.

In April 2022, around the same time as the park explosion, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) revealed that 8.5 million Iraqis live amidst landmines and deadly unexploded war remnants. These “deadly remnants continue to claim lives and cause devastating injuries,” stated the ICRC’s 2025 report. A total of 78 victims were reported as either killed or injured between 2023 and 2024. Three students also lost their lives in the explosion of a war remnant in the Abu Khaseib district of Basra in early 2025.

Shortly after, in May 2022, while several Iraqi families were spending time at the Al Seeba recreational park, an unfamiliar object obstructed a group of children from their playing, and they asked a municipal worker to remove it. The man tried to clear it away, but the object suddenly exploded; it turned out to be a landmine, taking his left leg. In the same year, two workers from the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS) were also killed, and a third was injured in an incident at a mine-clearance site.

In Al Bitran, mines and war remnants have reshaped both the land and the village’s identity. Once officially known as “Jurf al-Milh” (Salt Cliff), it is now called “the village of the amputees (Bitran)” due to repeated explosions and resulting disabilities, causing a sharp population decline.

Iraq’s Directorate of Mine Affairs (DMA) reported that the areas contaminated with mines and unexploded ordnance across the country’s central, southern, and western governorates amount to nearly 1,500 square kilometers. Basra accounts for the largest share at 46 percent, followed by Maysan governorate at 14 percent. The directorate announced in May 2025 an initiative to clear 200 square kilometers in Basra governorate.

After Raseef22 parsed through multiple reports, the evidence suggests a government shrouded in suspicions of corruption and negligence. Two dangerous factors were revealed as an explanation to the persistence of the crisis and the obstruction to any resolution; namely transference and selective clearance. Our investigation also highlights the experience of the village of Al Bitran, whose reality has been shaped by landmines and war remnants to the point that their traces cling to its very name — the amputees.

Who clears the mines?

Since 2012, three main entities have been responsible for Iraq’s mine clearance. These entities include the government effort represented by the Ministry of Defense, the engineering support and civil defense teams affiliated with the Ministry of Interior, and later the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) teams. There are foreign and local international organizations — over 50 — that rely on international grants as well as commercial companies, according to Nebras al-Tamimi, director of the Regional Center for Mine Action in the southern region.

The Iraqi Observatory for Human Rights (IOHR), a non-governmental organization that monitors human rights violations in Iraq, said Iraqi authorities “have received hundreds of millions of dollars in aid from countries and international organizations” since 2014, intended for mine and explosives clearance efforts, but support has declined over the years. The observatory believes this occurs for several reasons, including donors’ concerns that the funds were not reaching their intended destination due to government corruption. Raseef22 contacted the observatory, which said its assessment is based on an analysis of interviews with staff at international organizations and other data, without providing further details. The Directorate of Mine Affairs at Iraq’s Ministry of Environment did not respond to a request for comment on this or other allegations raised in the investigation as of the time of publication.

Al-Tamimi, for his part, confirms the decline in work for organizations specializing in mine clearance, adding that “the reduction of financial support from international donor agencies has led to the suspension of many organizations’ activities, while some international and local organizations continue their work despite limited funding.”

After Raseef22 parsed through multiple reports, the evidence suggests a government shrouded in suspicions of corruption and negligence.

Iraqi parliamentarians have also spoken about corruption and theft in the management of international support and financial allocations for clearing mines and war remnants. At the end of 2022, former MP and Secretary General of the Kafa Movement, Rahim al-Daraji, called on the Iraqi government to present detailed statistics from the Ministry of Oil. He requested information on the volume of funds “stolen” under the guise of delayed penalties resulting from the failure to deliver land cleared of mines and unexploded ordnance to oil companies participating in licensing rounds. These matters are overseen by the Directorate of Mine Affairs at the Ministry of Environment.

Al-Daraji explained that, depending on the contracts, these penalties range from $50,000 to $500,000 per day, and that fines for just two companies reached $1.2 billion in a single year. These financial penalties are imposed by Iraq’s Ministry of Oil when there is a delay in handing over land allocated to oil companies under licensing rounds because it has not been cleared of mines and unexploded ordnance on time. Oil companies require safe, mine-free land to operate. If the responsible authorities fail to clean and deliver the land as scheduled, they incur delay penalties because this disrupts the companies’ work and delays contract implementation.

Al-Daraji also pointed to corruption surrounding mine-removal contracts at the expense of Iraqi citizens. We contacted the former MP for further clarification, but he did not respond to our inquiries.

MP Alia Nassif also accused a former director general of the Directorate of Mine Affairs of involvement in “dozens of corruption cases,” noting that “corrupt political parties are manipulating the lives of Iraqis and taking their money behind the scenes and providing protection.”

Criticism of organizations’ work in mine clearance has not been limited to the country’s southern regions. In 2023, Abdallah al-Jughifi, a leader in the Anbar Alliance, called on the relevant authorities to open a corruption file on a foreign company specializing in mine clearance in western Iraq. He stated that “the Norwegian company has not completed its tasks despite its presence in Anbar for six years, because influential parties prevent holding that company accountable or allow any action against it,” and that “the company’s staff is small and does not match the huge quantities of unexploded war remnants in the western Anbar desert.”

“The working mechanism of the company in question is tainted by financial corruption, and the relevant authorities must open corruption files into the company’s work,” al-Jughifi explained, “which has led to the killing and injury of a number of police, army, and Popular Mobilization Forces personnel who were carrying out security duties” in the area.

Mehdi Al-Tamimi, director of the High Commission for Human Rights office in Basra, confirmed what he described as “mine transference,” saying some companies contaminate clean areas with mines to secure additional donor funding amid weak government oversight.

Are authorities a hindrance to the solution?

Mustafa Hamid Majeed, director of media at the Department of Mine Affairs of Iraq’s Ministry of Environment, recently shared, in a press interview at the end of February 2025, that the loss of maps related to minefields planted during the Iran–Iraq war represents a major obstacle and challenge to clearance operations.

According to Majeed, these maps were kept by the Ministry of Defense before 2003, when the US invasion of Iraq took place, the Iraqi army was dissolved, and the maps were lost. Iraqi Ministry of Environment advisor Jamal Atta reiterated the same concern in July 2025.

Additional challenges, according to Majeed, include the “difficulty of securing funding, the impact of the war with ISIS, and floods and erosion that caused what is known as ‘mine migration,’ where minefields move as a result of these floods and landslides.”

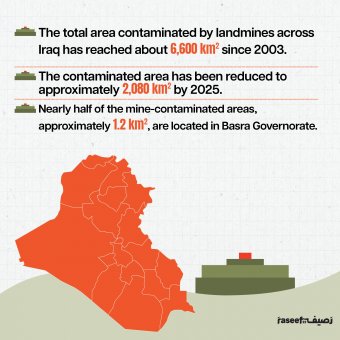

Official estimates of the extent of mine contamination in Iraq, both past and present, vary.

Reports indicate that it once exceeded 6,000 square kilometers and now stands at over 2,000 square kilometers.

According to Iraq’s Ministry of Environment, the total contaminated area discovered across the country since 2003 was around 6,600 square kilometers.

By 2025, that figure had been reduced to 2,080 square kilometers.

Al-Tamimi told Raseef22 that mine-contaminated areas in Basra amount to 1.2 square kilometers.

Meanwhile, the clearance effort relies on teams whose work cannot even cover 10 percent of the contaminated area, according to an estimate by the Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (IHCHR) in Basra — an independent body established in 2008. The Ministry of Justice is currently the authority temporarily responsible for managing its operations.

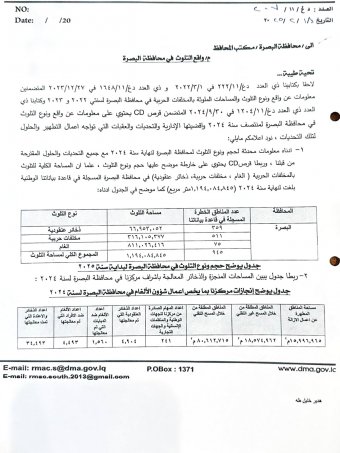

Type and scale of mine contamination in Basra at the beginning of 2025, according to the Southern Regional Center (RMAC South)

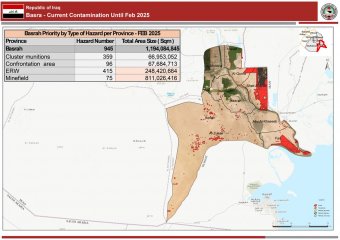

Map of mine contamination in Basra in 2025 | Source: Regional Mine Action Center (RMAC) - South

The deteriorating situation in Basra prompted its governor to call on the Ministry of Environment to clear the Shatt al-Arab District of war remnants to allow displaced residents to return and rehabilitate the agricultural land.

Transference – The mess of movement

During this investigation, we encountered statistics that revealed a clear discrepancy: mine-contaminated areas are increasing in some regions despite ongoing clearance efforts.

Some of our sources attribute this to what is known as transference: the transfer of mines from a contaminated area to another area that is mine-free, or that had previously been cleared..

A mechanical operator for a foreign organization in mine-clearance told Raseef22, on the condition of anonymity, that following the Al Seeba park incident and the site’s clearance in February 2025, he watched “workers in the organization transport mines from the Al Tannumah area (south of Basra) and replant them near the park again shortly before the incident occurred.”

The same source confirmed that these mines were transported in a private vehicle over a distance of 70 km to reach the Al Seeba area, where the village of Al Bitran is located.

The operator believes the intent behind this was to “expand the scope of work to continue receiving financial support, especially since the park is not monitored by security forces due to its distance from populated areas.”

Raseef22 is withholding the organization’s name as we were unable to independently verify the evidence provided by the source regarding his statement.

The same source said this was not an isolated incident. At the beginning of his work, he removed five to six cluster bombs per day and then moved about five kilometers away from the site. However, he noticed that vehicles transporting the mines would remain parked for long hours, although they were supposed to move immediately in case of emergency. When the team returned the next day, the number of mines in the secured container had dropped from five to one, in what he described as a suspicious pattern.

He added that transporters sometimes dug pits to bury cluster bombs, recorded the coordinates, and referred to the site as a “cemetery.” According to him, these locations functioned as storage sites for mines later retrieved and replanted elsewhere.

The source said he personally witnessed colleagues planting cluster bombs in cleared land in Basra to sabotage others and embarrass them before managers. He also claimed relocation operations did not follow safety procedures. In July 2025, a vehicle caught fire while someone was preparing food nearby; the incident was later described publicly as accidental.

Raseef22 contacted the organization, which said the judicial investigation was ongoing and that an internal review had led to measures to improve employee safety.

RMAC – South responded after the deadline for comment.

The source said that between 2021 and 2025, he repeatedly observed mine “transference,” including alleged theft. He said the Southern Regional Mine Action Center (RMAC – South) and security forces were informed but that investigations yielded no results. He also alleged he received threats from management after discovering the operations. Raseef22 was unable to independently verify these claims.

Mehdi Al-Tamimi, director of the High Commission for Human Rights office in Basra, confirmed what he described as “mine transference,” saying some companies contaminate clean areas to secure additional donor funding. He attributed the phenomenon to weak government oversight and declined to share evidence, citing witness protection. He said the issue was raised in a letter to the Basra Provincial Council in August 2025.

Al-Tamimi cited Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA) as an example. NPA obtained its Iraqi license in 2022 after meeting operational requirements and was assigned work in southern Iraq, including Shatt al-Arab District. The organization says it has worked in Iraq since 1995 and is currently the only international NGO supporting the government in mine clearance in southern Iraq.

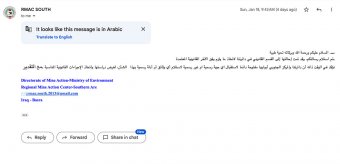

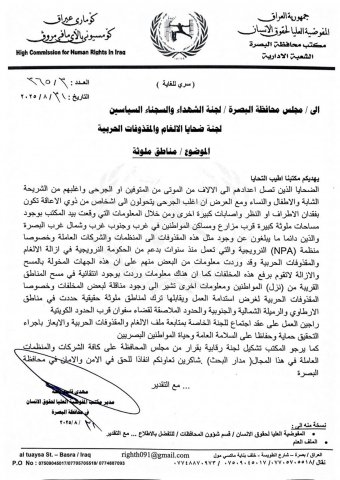

Official document by the High Commission for Human Rights in Iraq, citing reports of mine transference by certain organizations such as the NPA

In response to the allegations, NPA said no official complaint had been filed with RMAC – South. It stated it takes such claims seriously and would investigate if credible evidence were submitted. It also said it had contacted the Basra human rights office and was awaiting documentation.

The former employee said transferring cluster bombs by vehicle could be deadly and alleged that large clearance areas are assigned to expand work and secure grants. His account echoes remarks by former MP al-Daraji, who alleged in a television interview that corrupt officials and companies plant mines, photograph them, and secure contracts worth up to $60 million, completely disregarding civilian safety for profit.

Selective clearance

Al-Tamimi pointed out that many contaminated areas are near people’s homes and farms, west, southwest, and northwest of Basra. Residents often report the presence of these munitions to the organizations and companies operating there, seeking help in removing them so they can live and work safely.

“We have information confirming that the bodies authorized to survey and remove these remnants do not clear them,” al-Tamimi told Raseef22.

According to him, there is selectivity in which areas are surveyed. Typically, the relevant organizations and companies working, “especially the Norwegian organization,” operate in areas nearby residential homes. The projects are framed as more urgent, and therefore attract more financial support from donors.

Al-Tamimi believes this selectivity leads to repeated accidents among families, particularly among young people, children, and women, who go out during the spring into contaminated areas, resulting in casualties.

“The provincial council needs to seriously follow-up about the unsurveyed lands,” he stressed, adding that the committee for victim assistance, tasked with providing support and assistance to victims of mines, war remnants, military operations, and terrorist acts, remains limited in effectiveness, “despite cooperation with some British companies.”

“Orchards once covered Al Bitran. But the mines have bulldozed the lands and displaced hundreds. The people who lost their limbs are unable to find work, exacerbating the population’s impoverished living conditions.”

In response to accusations of “selectivity,” the NPA told Raseef22 that the distribution of tasks regarding the priority of clearing contaminated areas lies with the Directorate of Mine Affairs in Iraq, which sometimes delegates this responsibility to the Southern Regional Mine Action Center (RMAC - South). NPA also stressed that its responsibility is limited to “conducting survey and clearance activities accurately,” in accordance with the instructions of the responsible authority.

Our anonymous source, the mechanical operator, shared the unclear standards and the absence of a professional work plan at his organization.

He recounted that during his former organization’s work in South Rumaila, particularly on farmland, farmers would report mines—referring to them as a “luqma”—and ask that they be removed so they could cultivate their land. According to him, the mines were often not removed, for no clear reason, suggesting the organization ignored the farmers’ requests and chose clearance areas based on its own priorities.

Death traps surround “Al Bitran”

In Al Bitran, mines and war remnants have reshaped both the land and the village’s identity. Once officially known as “Jurf al-Milh” (Salt Cliff), it is now called “the village of the amputees” due to repeated explosions and resulting disabilities. The village, covering about 2.5 km², has seen a sharp population decline. Many residents were displaced, first during the escalation of the Iran-Iraq war in 1982 and later due to ongoing mine incidents. Only a small number remain, according to village mukhtar Jaafar Mohammed, 69.

Located along the former Iraqi-Iranian front lines, the area became heavily mined, contaminating 4.5 km² within the Shatt al-Arab District. Disabilities are visible in daily life: vendors in the market use wheelchairs, and some residents rely on crutches. The mukhtar Jaafar said mines remain scattered among homes, and children grow up playing near them, accustomed to the danger.

“Orchards once covered Al Bitran,” Jaafar said. “But the mines have bulldozed the lands and displaced hundreds. The people who lost their limbs are unable to find work, exacerbating the population’s impoverished living conditions.”

One resident, Karrar Haidar, 21, lost his left leg in August 2023 when a landmine exploded as he was heading to work near the Shalamcheh border crossing, about 30 km from Basra. He said mines are clearly visible in the area and criticized what he described as a lack of serious removal efforts by authorities and clearance organizations.

“Anyone who visits the Shalamcheh border crossing can clearly see the mines. The same is true in the Shatt al-Arab District, where these areas still suffer from the presence of war remnants,” Haidar told Raseef22. Haidar warned that residents face constant danger near border crossings, sometimes without warning signs, despite the presence of multiple clearance organizations working with the Directorate of Mine Affairs (DMA).

Karrar Haidar, 21, lost his leg when a landmine exploded as he was on his way to work

The village mukhtar confirmed that warning signs once existed but were removed by clearance organizations. He said no adequate replacements or awareness campaigns were introduced, leaving residents without clear safety guidance.

Saif al-Salmi, 36, another resident, said there are no signs indicating mined areas, except occasional markings after an explosion. He added that an acquaintance was recently killed in a blast in the absence of warning signs.

A video documents the presence of mines without warning signs

Women and girls of Al Bitran: Silenced victims by force

Our field visit to the village of Al Bitran revealed the discrimination and violence faced by girls and women with disabilities as a result of mine and war-remnant incidents, compared with male victims of these incidents, including limited job opportunities and the right to marriage and childbearing.

Zainab Hamid, 18, fought back her tears as she told Raseef22 how her life had changed “in an instant” after a landmine exploded near their family home in March 2020. Hamid lost her sight while her brother was left with a permanent disability.

Zainab Hamid speaking about her dreams

Zainab was forced to leave school during her final year at elementary school to support the family by helping her mother gather wild herbs and sell them to earn a living.

“We knocked on the doors of doctors across Iraq to no avail,” her father, Hamid Jaber, 69, told Raseef22,. “All I hope for today is that Zainab might regain her sight, even just a glimmer of it. But what stands between us and this dream is sums of money beyond our means.”

Zainab also complained that the appropriate healthcare is nonexistent in the village, and that women with disabilities face difficulty moving around freely, especially at night, to access health services or receive necessary medical care, as compared to men. This problem is compounded by personal safety concerns, such as fear of assault and harassment, in addition to the lack of transportation suited to their needs.

“Even the most basic necessities of life, such as medicine, food, and healthcare services, are not available to us,” she said. “Patients, especially women, wait for days, and the hospitals, which are far from the village, cannot meet their needs, as if misery has become part of their lives.”

During our meeting, sorrow was clearly visible on Zahra’s face, who, like other women with disabilities in the village, has been affected by gender and ableist discrimination. In comparison, men, who are seen as the family’s breadwinner, with disabilities may receive more communal support and consideration for work, marriage, and children.

Mukhtar Jaafar also noted that the village lacks health centers capable of meeting the needs of people with disabilities. He explained that the specialized health services available are limited to the Al-Ashar area in the city center, about 35 to 45 kilometers from Al Bitran — a long distance that creates additional challenges for people with disabilities in the village, especially women, given the social and economic restrictions on their movement even when seeking treatment. Jaafar noted that most residents received nothing more than a welfare salary (roughly USD $154 per month), which hardly covers a family’s basic needs.

Zahra, 49, lost her sight in a landmine explosion while harvesting her crops.

“I woke up after three days of being unconscious to strange voices, and then realized they were the voices of doctors and police officers,” she told Raseef22.

The incident occurred on the outskirts of Al Bitran in 1997, when Zahra was a young woman. She lost her sight, suffered severe wounds and fractures to her hands and left leg, which doctors tried to repair with platinum. Zahra later learned her sight could be restored if she were granted financial assistance from the government to undergo the necessary operation.

During our meeting, sorrow was clearly visible on Zahra’s face, who, like other women with disabilities in the village, has been affected by gender and ableist discrimination. In comparison, men, who are seen as the family’s breadwinner, with disabilities may receive more communal support and consideration for work, marriage, and children.

There are no accurate statistics in Iraq on the prevailing stereotypes and social constraints imposed on disabled women, a reflection of how Iraqi women’s struggles linger in the shadows, away from official records and public data.

“Women with disabilities face double discrimination, as they are viewed with prejudice twice,” said Lodia Raymond, an Iraqi feminist and activist. “Once because they are women, and again because of their disability.”

Returning to Raed, the father of 12-year-old Zainab, he bitterly explained to Raseef22 how his daughter was deprived of her right to education.

“I had to keep her at home because there is no suitable transportation adapted to her health condition. Even nearby schools lack special chairs and facilities for people with disabilities, which makes enrollment very difficult,” he said. There is one private school for people with disabilities, but he could not afford the tuition, illustrating how the absence of government support leaves children like Zainab out of school despite their strong desire to learn.

“She deserves an education, and a prosthetic limb that would allow her to rely on herself more and live a normal life,” he said.

Sundus Ne’ma, 40, a Basra-based journalist and activist, documented the suffering of women with disabilities in Al Bitran and other areas in Basra.

“Women with disabilities face clear discrimination due to the stereotype that society imposes on them, which makes them feel inadequate and incapable despite their abilities,” Ne’ma told Raseef22.

As a result, disabled women suffer severe marginalization in accessing job opportunities, due to the absence of policies that support their integration into the labor market, in addition to the lack of marriage prospects because of false perceptions that see disability as an obstacle to married and family life.

Dr. Awatif al-Mustafa, director of the Al-Taqwa Association for Women’s and Children’s Rights, explained that the association has carried out awareness campaigns and provided social integration sessions. It also launched the campaign “Women with Disabilities Are Iraqis Too,” through which they were able to provide plots of land to a number of women with disabilities and secure an annual employment quota of 5 percent for them, in addition to providing special facilities in government offices and offering them priority without having to stand in lines.

“Women with disabilities face double discrimination, as they are viewed with prejudice twice,” said Lodia Raymond, an Iraqi feminist and activist. “Once because they are women, and again because of their disability.”

Victims on the rise, solutions absent

According to the director of the Southern Regional Mine Action Center (RMAC - South), Nebras al-Tamimi, “the number of registered victims in the village of Al Bitran due to mines is estimated at 123 people, including deaths and injuries.”

Meanwhile, in the Basra governorate, the world’s highest mine-contaminated city, there are more than 5,300 registered victims, and the figure is expected to rise (in the second phase of the field survey) to 10,000 victims.

While Nebras acknowledges that Al Bitran is one of the villages devastated by mines in Iraq, he also praised the government's efforts in clearing high risk areas and promoting risk-awareness campaigns in recent years.

“After restrictions were imposed on the work of international organizations in Iraq, such as the suspension of grants from international donors, especially those from the United States, our work was greatly affected,” he said. “We are facing slow progress, and there are planned areas we must adhere to. A single team in a minefield can only clear a maximum of 200 square meters per day.” Mohannad Hussein, assistant director of media at the Popular Mobilization Forces, shared that the cost of clearing war remnants in Iraq ranges between one and five dollars per square meter.

“Even the most basic necessities of life, such as medicine, food, and healthcare services, are not available to us. Patients, especially women, wait for days, and the hospitals, which are far from the village, cannot meet their needs, as if misery has become part of their lives.”

Since 2015, the Government of Denmark has contributed more than $41 million to the United Nations Mine Action Service program in Iraq. The European Union also provided a financial grant of 5 million euros (approx. $6 million) dedicated to mine-removal operations on agricultural land in Basra Governorate, with the aim of rehabilitating land and supporting local farmers’ livelihoods. Germany funded and supported mine-removal projects in Iraq with more than $100 million between 2016 and 2023, making it one of the largest donors.

Documentation by the Research Department of the Iraqi Parliament on violations in the work of agencies responsible for clearing mines and explosive war remnants between 2020 and 2023 indicates an increase in contaminated areas that have not yet been addressed, particularly in Diyala, Babil, and Basra. It also highlights the failure to utilize the £400 million British loan allocated to the Ministry of Environment under the Federal General Budget Law for 2023–2025, provided by UK Export Finance (UKEF) for mine-removal operations.

The parliamentary research further revealed that mine-detection equipment obtained through international grants remains stored in departments of the Directorate of Mine Affairs and unused due to the absence of executive activity. The directorate also did not supply this equipment to the Ministries of Defense and Interior or the Popular Mobilization Forces for detection and clearance operations.

What about government funding?

The Iraqi government has allocated funds to the ministries and relevant executive bodies, including the Ministries of Defense and Interior and the Popular Mobilization Forces, according to al-Tamimi.

In a recent report by the Directorate of Mine Affairs, government funding for demining operations amounted to about $81 million between 2012 and 2022. Additionally, under a plan linked to the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM), the Iraqi government allocated an amount equivalent to 20 billion Iraqi dinars (about $17 million) over three years to support the cluster-munitions clearance program.

During 2024–2025, reports indicate that funds were allocated in the Iraqi budget for “support in the south” under the munitions-removal program, but it is unclear whether the required additional national funding was fully secured.

“After restrictions were imposed on the work of international organizations in Iraq, such as the suspension of grants from international donors, especially those from the United States, our work was greatly affected. We are facing slow progress, and there are planned areas we must adhere to. A single team in a minefield can only clear a maximum of 200 square meters per day.”

Basra Provincial Council member Nawfal al-Mansouri said the governorate needs between $1 and $1.5 billion to complete clearance operations. He noted that this is only an estimate and may be lower than the actual amount, given the lack of accurate maps detailing the extent, type, and distribution of contamination.

Nebras al-Tamimi believes the government support for the Ministry of Environment’s mine-removal program is limited, with funding largely restricted to operational allocations. He stressed the need for international cooperation, including support from the United Nations and local authorities, to reduce the scale of the problem.

In August 2025, the Ministry of Environment appealed for a special budget for the Directorate of Mine Affairs to ensure logistical support and sustain land-clearance operations, indicating that current funding is insufficient.

The long-term environmental consequences

Concerns about the consequences of the slowdown and potential suspension of clearance operations due to insufficient funding are accompanied by fears of worsening environmental harm.

According to the Directorate of Mine Affairs, mines and unexploded ordnance have led to the shrinking of agricultural land use and, consequently, a decline in the production of key crops, as farmers have abandoned their villages, especially near the borders, and moved to barren desert lands unsuitable for cultivation.

Mines have also polluted the marine environment of the Shatt al-Arab and contributed to the displacement of residents from marsh and wetland areas in southern Iraq after they were dried up. Many residents have refrained from fishing in areas suspected of mine contamination. As a result, fish stocks have declined.

Meanwhile, a study by the Iraqi Parliament indicated that lands that were supposed to be cleared of danger in the 20th century were never invested in or utilized, as mine-clearance procedures were not completed, preventing the use of those lands. As a result, the total cultivated area reached about 378 square kilometers across several governorates.

“Basra still suffers from deep environmental damage left by successive wars, from the Iran–Iraq war to later internal conflicts,” environmental expert Khaled Sulaiman told Raseef22, stressing that these impacts “are no longer merely side effects of wars but have become part of a complex environmental crisis threatening the stability of the province’s natural systems.”

Sulaiman reveals that the removal and uprooting of millions of palm trees was among the most dangerous consequences of those wars, noting that the palm tree “is not merely an agricultural element, but a vital component of the local environment that helps absorb carbon, reduce temperatures, and protect the soil.” The disappearance of this vast vegetation cover has turned large areas of fertile land into barren zones that have lost their productive capacity.

Sulaiman also notes that the marine environment in the Shatt al-Arab has not been spared from deterioration, as wrecked ships and rusted military equipment are scattered there, along with oil pollutants that have directly affected marine life and natural habitats in the area.

For its part, the World Bank warned in a report on contaminated areas in Iraq and the repercussions of government shortcomings in addressing polluted land, noting that about 2.4 million hectares of arable land have been affected by war remnants, along with long-term impacts on the safety, health, and livelihoods of residents.

The report also suggested that the successive wars and military operations caused heavy losses and inflicted damage estimated at 3.5 trillion Iraqi dinars (approx. $3 billion) across the oil, agricultural, and industrial sectors.

Mines and unexploded ordnance have led to the shrinking of agricultural land use and, consequently, a decline in the production of key crops. Mines have also polluted the marine environment of the Shatt al-Arab and contributed to the displacement of residents from marsh and wetland areas in southern Iraq, resulting in declined fish stocks.

Agreements awaiting implementation

Iraq officially joined the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production, and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on Their Destruction, known as the Ottawa Treaty, on 15 August 2007, entering into force on 1 February 2008.

The Ottawa Treaty is an international convention that prohibits member states from producing, possessing, transferring, or using mines. It currently includes more than 164 state parties, making it a stable legal and moral international standard. The United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross oversee support for its implementation and monitor states’ compliance.

“Our national efforts were focused on liberation operations [from ISIS] after 2014, so the implementation of the convention was delayed,” spokesperson for the Iraqi Ministry of Environment, Luay al-Mukhtar, told Raseef22.

What currently hinders it, al-Mukhtar said, is the lack of financial support, which does not match the scale of the country’s contamination. Iraq should have eradicated mine contamination by 2023, but it requested an extension until 2028 due to increased contamination.

The current capacities and capabilities of the Iraqi government will not enable it to remove mines definitively, as clearing this quantity of mines requires decades, in addition to the fact that demining is among the most difficult, complex, and dangerous activities. At the same time, there are deviations in the implementation of the international agreements signed by Iraq regarding the ban on mines and explosive munitions. The Directorate of Mine Affairs at the Ministry of Environment indicated that this deviation is due to the very high level of mine contamination in Iraqi territory, which does not match the available capabilities, in addition to the directorate’s failure to specify implementation rates of those agreements to assess progress.

l-Tamimi insists that only unified, coordinated efforts can truly clear Iraqi land and achieve “zero contamination.” He warns that the international agreements Iraq has signed—morally and humanly binding—must be urgently and genuinely enforced, not merely upheld in name.

He calls for rigorous monitoring of both domestic and foreign clearance organizations, with strict oversight by intelligence and national security agencies, as well as provincial councils—especially those representing communities whose residents stand to lose the most if the crisis continues to be neglected.

*Given the sensitivity of this investigation’s subject matter, the ongoing danger that journalists are subject to in the region, and the security considerations of writing about Iraq while living in the country, the authors of this investigation requested anonymity. The writers are from southern Iraq, and, as such, relied on a number of local journalists to conduct their interviews on the ground or with officials. Contributing journalists also requested anonymity.

* Exchange rate: 1,300 dinars per US dollar.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!