Upon arriving in Nahrawan, pillars of black smoke can be seen rising from the Brick Factory complex, cloaking the sky above in a cloud of fumes. Here, factory owners burn fuel residue to convert sand into bricks (the primary material used for construction in Iraq).

The town of Nahrawan is northeast of Baghdad, 35 km away. According to the Ministry of Environment, Nahrawan is home to over 360 brick production factories.

This investigation explores the environmental repercussions of these factories and their use of fuel and black oil residues, as well as their impact on the women working there. We also examine Iraq's commitment to certain international agreements in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Aerial footage reveals the extent of smoke and dust emanating from the chimneys of Nahrawan's brick factories

This investigation explores the environmental repercussions of these factories and their use of fuel and black oil residues, their impact on the women working there, and Iraq's commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Slowly killing workers

Amidst the factories’ smoke and toxic fumes, Khalida Atewi, 51, battles her chronic illness. After having worked in these factories for two decades, Atewi suffers from chronic respiratory inflammation, also known as asthma, and must regularly use artificial respiratory devices and seek respiratory treatment.

Before working in a brick factory, Atewi lived with her family in the rural southern area of Diwaniya, 181 km south of Baghdad, and earned her living through farming and animal husbandry. However, droughts in the area forced her and her family to migrate in search of better opportunities.

Documents confirm Umm Haidar's affliction with several respiratory diseases

Documents confirm Umm Haidar's affliction with several respiratory diseases

Documents confirm Umm Haidar's affliction with several respiratory diseases

Documents confirm Umm Haidar's affliction with several respiratory diseases

Documents confirm Umm Haidar's affliction with several respiratory diseases

Documents confirm Umm Haidar's affliction with several respiratory diseases

Documents confirm Umm Haidar's affliction with several respiratory diseases

Documents confirm Umm Haidar's affliction with several respiratory diseases

Atewi is not the only victim of these toxic pollutants. Most factory owners in the area rely on a female workforce as they demand lower wages than their male counterparts. The use of oil waste at the Nahrawan Brick Factory Complex has affected many of its female workers.

Ahlam Jassim, another worker at the Nahrawan factories, has thus far undergone 3 surgeries for her kidney failure. Yet, even that has not been enough to cure her disease caused by her daily inhalation of smoke and dust.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Medical documents proving Ahlam Jassim's kidney failure.

Inside the basic mud home built Jassim lives in with her husband and three children, she struggles to survive without access to certain basic necessities. The lack of a healthy environment induces despair, and the financial strain of her treatment presents an added burden. Her factory salary barely covers the family’s needs. She spends long hours working, engulfed in toxic dust and smoke, without any job security or health insurance. This is in contradiction to Iraqi labor laws on female employment, which we uncover during our investigation.

Ahlam Jassim, a worker at the Nahrawan factories, has undergone three surgeries for her kidney failure. Yet, even that has not been enough to cure her disease caused by her daily inhalation of smoke and dust.

During our visit to the factories of Nahrawan, we met several women, all affected by their years of long work and prolonged exposure to toxic smoke and dust. Maliha Awad, 42, is one such woman. After her skin cancer spread, a doctor advised her to amputate part of her foot. Disabled and alone facing an uncertain fate, her health gradually deteriorates. Awad’s brother checks in on her and helps with certain basic daily tasks. She and her brother blame her long years of labor in the smoke-filled factories, and the scorching temperatures, with no support or for her current state, without any support or sponsor. This is the fate of many women like Maliha Awad.

The law and women's labor

Iraqi law (Article 85 of Labor Law No. 37, instated in 2015 and published in Al-Waqā'i' al-'Irāqiyah) strictly prohibits employing women for strenuous or health-compromising labor. This law is disregarded by the Nahrawan Brick Factory Complex, where women work grueling shifts, from 6 am to 6 pm under the scorching Iraqi sun, which often exceeds 50 celsius.

Lawyer Akram Hussein Aday confirms that the practices of these brick factories are inconsistent with Iraqi labor laws. Not only is the strenuous nature of the work detrimental to women's health, but the long working hours contradict Article 67 of the Labor Law, which outlines a maximum of 8 working hours per day.

Victims of a slow death

Some activists view the plight of these factory women as an extension of how women in Iraq have suffered, and continue to suffer, throughout history. Ahrar Al-Zalzali, a journalist focused on women's issues and president of a human rights organization, describes working in the Nahrawan factories as a slow death. It is imperative that women’s rights organizations and other relevant authorities intervene.

According to Al-Zalzali, it is unreasonable for women regardless of age to engage in physically demanding work with such severe physical and psychological implications. The repercussions of exposure to these toxic conditions include the onset of disease– some with rapidly appearing symptoms, such as respiratory diseases, and others that develop over time, such as cancer and other chronic illnesses. Moreover, certain diseases can affect the health of newborns during childbirth.

Al-Zalzali condemns these inhumane working conditions as a blatant violation of women and human rights, where victims are driven to work at a toxic slaughterhouse, with no intervention from the relevant authorities to save them from their inevitable fate: a slow death.

Journalist Ahrar Al-Zalzali condemns the inhumane working conditions at the Nahrawan brick factories as a blatant violation of human rights. Victims are driven to work at a toxic slaughterhouse to face their inevitable fate: a slow death.

What are fossil fuels?

As detailed by Beatona - Our Arab Environment, a magazine specializing in environmental issues, fossil fuels cause significant pollution when burned.

Emissions from the combustion of traditional and black oil fuels in brick and asphalt factories contribute to environmental destruction. Pollutants include carbon dioxide (CO2) and carbon monoxide (CO) as well as particulate matter suspended in the air, including sulfur dioxide, CO2, nitrogen oxide NO and ozone O3.

The information outlined in Beatona aligns with the statements of Mohammed Ahmed Najmuddin, a researcher and a Master of Environmental Engineering. Najmuddin explains that air pollutants are primarily determined by the type of fuel used. Black oil is considered to be one of the most dangerous types of fuel due to its content of sulfur compounds, sulfur oxides, nitrogen oxides, and suspended particles that result from the combustion process. These are some of the most dangerous known air pollutants, they directly affect those exposed.

A number of environmental organizations claim to have submitted evidence of violations to the Ministry of Environment from some of the victims affected by these environmental breaches. However, no action has been taken to mitigate these issues to date.

Qutaiba Jawad Kadhim, a member of the Tawasul organization and director of Environmental Platform, a project monitoring environmental violations, confirms that there have been numerous complaints regarding the suffering of the Nahrawan residents and workers.

Jawad explained, “As a supervisory entity for environmental violations, we have sent reports, findings and complaints about the use of heavy traditional fuels by the factories in Nahrawan to the Ministry of Environment Citizens Affairs Department and to the Environmental Police Department. And we are making efforts to communicate with other entities tackling environmental issues, but the problem persists.”

Field verification

In order to verify some of the testimonies we received, and despite the threat of factory owners and the absence of regulatory bodies, we reached out to Hussein Jabbar, professor of Environmental Engineering at the University of Baghdad.

After presenting Jabbar with our findings, we decided to conduct a specialized scientific investigation into the pollutants from the use of fuel waste and the burning of black oil at the Nahrawan Brick Factory Complex.

We identified six points on the map for scientific measurement and determined the factory’s working hours and burning times. Modern air quality measurement devices were used to assess air quality and pollution levels.

Results on the air quality devices used indicated "unhealthy"

Results on the air quality devices used indicated "unhealthy"

Results on the air quality devices used indicated "unhealthy"

Results on the air quality devices used indicated "unhealthy"

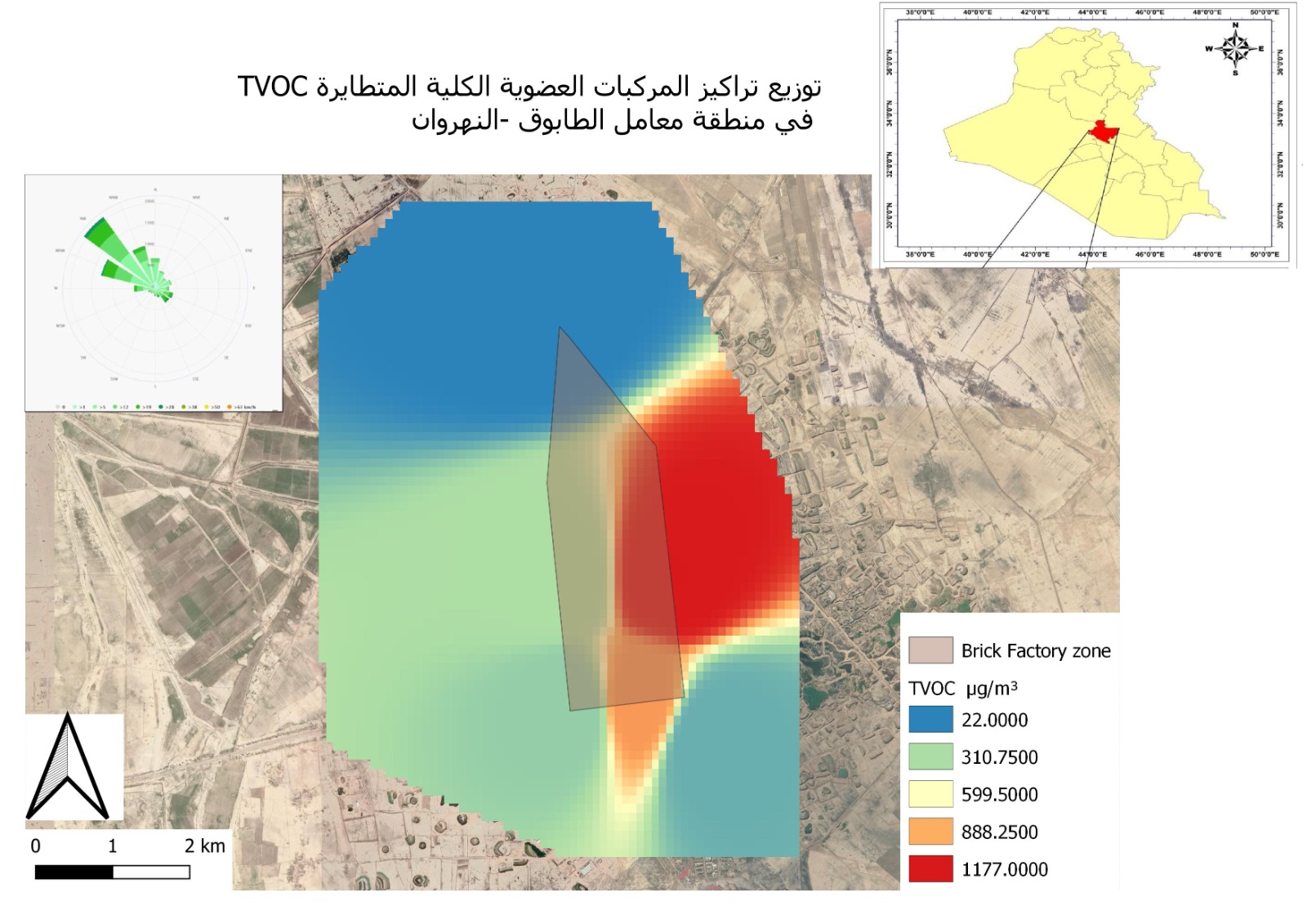

According to the results obtained, the air quality sampled and the smoke particles tested were shockingly more dangerous than local and global standards ratios. These findings, as outlined in the following diagram, confirm the validity of the testimonies we received from factory workers.

Distribution of toxic fumes in Nahrawan's factory zone

Distribution of toxic fumes in Nahrawan's factory zone

Our findings reveal that pollution from the factories of Nahrawan has spread throughout the entire vicinity. All nearby residents are thus exposed to toxins, smoke and consequently disease.

Our findings have revealed that pollution from the brick factories of Nahrawan has spread throughout the entire vicinity, and all nearby residents are exposed to toxins, smoke and consequently disease.

The young and the old, nobody is spared

Here in Nahrawan, smoke from the brick factories hangs heavy in the air and spreads disease among the young and the old alike. 16-year-old Fatima was born with a birth defect that has forced her into a life of isolation and prevented her access to education. Fatima’s father, Adnan Kamal, 44, tells his story, which began twenty years ago. At that time, he lived in a modest house between the factories, due to its close proximity to work. Kamal laments, “since then, we have suffered nothing but disease from having inhaled the smoke of the factories.” Fatima is not the only victim, he himself suffers from respiratory disease and shortness of breath. Everything he earns working in the factories is spent on his daughter’s treatment, who, in addition to her birth defect, also suffers from respiratory problems and a deformed heart valve.

Kamal and his family have no means to obtain affordable medicine apart from by seeking the attention of a local makeshift medical practitioner whose practice is a primitive room. He laments their fate, and claims that he and his family would be free of disease had they sought opportunity in a different region.

16-year-old Fatima Adnan, a resident of Nahrawan, suffers from a birth defect that forced her to be deprived of her education

16-year-old Fatima Adnan, a resident of Nahrawan, suffers from a birth defect that forced her to be deprived of her education

Several studies have confirmed that the primary cause of pollution and disease in Nahrawan is due to the local factories’ use of black oil and its subsequent combustion, according to Ahmed Sameer Naji at Al-Muthanna University.

Iraq and international treaties

In 2021, the Iraqi Cabinet approved the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) document on climate change, indicating Iraq's adherence to the Paris Agreement on climate change. The Paris Agreement, adopted by 197 countries in December 2015, aims to significantly reduce global greenhouse gas emissions and limit the increase in global temperature to well below 2 degrees Celsius, with efforts to limit it to 1.5 degrees.

According to the NDC document, Iraq aims to implement its specific contributions nationally for the period from 2021 to 2030, achieving an expected reduction of 1-2% of total emissions based on the national greenhouse gas inventory, and 15% with international financial and technical support. This aims to empower vulnerable sectors in Iraq to adapt to climate change measures.

Iraq has committed to introducing development and rehabilitation operations for certain industries, including the industrial sector.

These pledges oppose our findings from the Nahrawan brick factories, which indicate dangerously high pollution rates.

"When the alternative is available, we will become environmentally friendly"

Some owners of brick factories in Nahrawan did not deny our findings.

Safaa Abdulwahed, spokesperson for the Brick Factory Owners Association and owner of one of these factories, explains that factories are forced to use these harmful fuels due to the lack of government support and more cost-effective alternatives. The low cost of black oil forces keeps them using it, while they await government support to develop more sustainable factories, as in other countries across the world.

Abdulwahed emphasizes that this is a costly process, and one that requires government support. It is necessary to provide these factories with alternative fuel at a subsidized price, to sustain their operations which ultimately provides Baghdad with its construction material.

Black oil: The cheapest in Iraq

When asked about abandoning the use of black oil and fuel waste, Abdulwahed retorts, “When an alternative to black oil is available, we will convert our factories into environmentally friendly ones.”

Smoke from the factories hangs in the air, spreading disease among the young and the old. 16-year-old Fatima was born with a birth defect and her father suffers from a respiratory disease. His factory salary goes towards his daughter’s treatment.

The intersection of responsible authorities exacerbates the problem

Mohammed Hameed AbdulMajeed, Assistant Director-General of the Industrial Development Department at the Ministry of Industry, responsible for licensing and monitoring these these factories, blames the Ministry of Environment for abandoning its responsibility to make them more environmentally friendly, and the Ministry of Oil for not providing an alternative to black oil.

According to him, both ministries should provide the educational resources necessary to make the factories environmentally friendly.

Dr. Raghad Assad Al-Obaidi, director at the Ministry of Environment, refutes the statements of the Industrial Development Department. She claims that “the role of the Ministry of Environment is supervisory and regulatory. We have contacted the Ministry of Industry Department of Industrial Development in regards to providing factories with modern incineration machinery, but they have not acted. The incineration mechanisms at the factories do not include filters to reduce emissions.”

Al-Obaidi added that the surrounding land is also polluted and unsuitable for agriculture, and urged the Ministry of Agriculture to cover the land with plants.

According to Al-Obaidi, the Ministry of Oil has not responded to requests to provide factories with lower-sulfur fuels.

The cross-over and blaming between responsible government entities further complicates the situation in Nahrawan, despite all parties acknowledging the validity of our findings and the emission of toxic pollution from the local brick factories. Amir Al-Hassoum, a spokesperson for the Ministry of Environment, explains that the Ministry limits itself to issuing warnings to owners of violating factories. These warnings come as a result of dense emissions from the use of black oil, the failure to plant trees around the factories, and the use of old production methods.

However, these warnings will not restore the health of the women in the factories, which has been robbed of them. Many of these women now reside in dilapidated shelters and mud rooms, facing incurable diseases and enduring slow, agonizing deaths.

This report was produced as part of the Aswatouna (Our Voices) project implemented by Internews

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!