She sat just a few meters away, eating from a plastic plate while the rest of us laughed and posed for photos. No one paid her any attention. When it was time to eat, no one brought her a chair or invited her into a photo.

We were at a friend’s birthday picnic in Baghdad. The atmosphere was lively, the food abundant, and everyone seemed to be enjoying themselves, except for her. She was a young African woman, the family’s domestic worker who spent the celebration caring for a toddler. I didn’t know her name, how she was doing, where she was from, nor what languages she spoke.

Just like the others, I simply didn’t ask. This is how it is in Iraq, which has seen a meteoric rise in the number of domestic workers. The day-to-day life of domestic workers living in Iraqi households, the abuse, and systemic neglect are often-overlooked, but one disturbing Facebook page aggregates these attitudes publicly and unapologetically. What seemed to be a practical forum soon revealed the darker, disturbing attitudes in Iraq towards migrant domestic workers beneath the surface.

Iraq’s invisible workforce

Iraq has seen a rise in migrant domestic workers from 1,000 in 2007, 50,000 in 2018, to 1 million as of 2024. Only 7 percent of these workers are registered in the social security system. Approximately 90 licensed migrant domestic worker recruitment agencies operate in Iraq, while others recruit workers illegally. This surge is presumably driven by Iraq’s post-war reconstruction efforts, a growing demand for affordable household labor, and loosely regulated or porous border controls.

Despite this rapid growth, there is a lack of reliable data, official figures on the total number of workers, their roles or specializations, and their countries of origin remain incomplete, making it difficult to assess the full scale and nature of this labor trend.

For many women from Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, and other countries in the Global South, limited opportunities, high unemployment, and political or economic instability in their home countries push them to seek work abroad. These women typically pay local agents around $500 USD for contracts signed upon arrival. Many endure long hours, low wages, and harsh conditions, far from what they were originally promised.

The writing on the wall

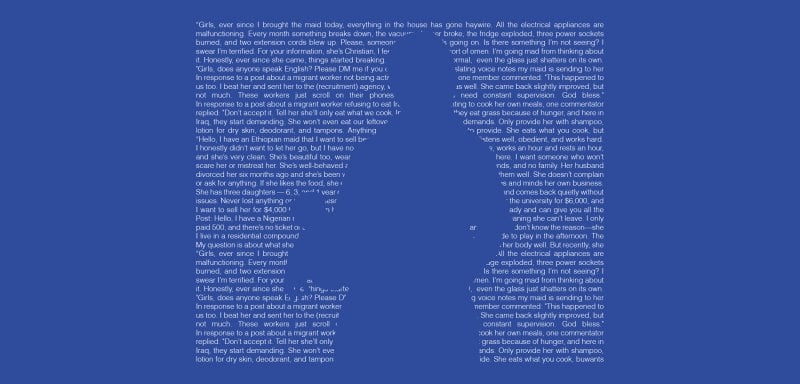

I started speaking to friends and contacts who employed migrant domestic workers, seeking their feedback. Their responses seemed rehearsed. My curiosity led me to a Facebook group based in Iraq with over 10,000 members hiring domestic workers.

The group was created in October 2023. There are four active administrators and one moderator. I reviewed more than 500 posts and approximately thousands of comments and replies, most of which were shared anonymously or under pseudonyms.

Scrolling through the posts, the tone shifts rapidly, from routine advice to control, suspicion, and mistreatment of workers.

One Facebook user shared that her domestic worker seemed “cursed” because every appliance stopped working after her arrival. Another user described deducting wages because she was “tired of the damage” the worker caused. “She broke everything in my house,” the post read, “so I started cutting her pay.”

Another user chillingly admits to confiscating her Nigerian domestic worker’s passport for six months and offering to sell her for $4,000, describing her as “healthy” and capable, but unwilling to care for children. This post, and the ones that follow, reveals a clear sign of human trafficking.

Other posts in the group include withholding wages, enforced isolation, limited phone access, and threats of deportation—all clear indicators of exploitation and control. “Common [labor] violations include passport confiscation, physical and verbal abuse, and informal ‘reselling’ of workers between households,” says Abdullah Khalid, founder of Peace and Freedom Organization (PFO), an Iraqi NGO promoting human rights, labor rights, and social justice. “Some end up homeless or trafficked into sex work.”

Few workers understand the contracts they sign, and almost none receive legal orientation, according to Khalid. “They’re unprotected from the moment they arrive,” he says.

One post blatantly reveals the degree of objectification normalized in Iraqi households: “I have an Ethiopian maid I want to sell because I have to travel,” reads the post. “She’s lively, listens well, obedient, clean, and wears makeup. Sleeps and wakes on time. Has no friends or relationships here. I bought her for $6,000 and will sell for $4,000. Message me if serious, I’ll send details and photos.”

“I have an Ethiopian maid I want to sell because I have to travel,” reads the post. “She’s lively, listens well, obedient, clean, and wears makeup. Sleeps and wakes on time. Has no friends or relationships here. I bought her for $6,000 and will sell for $4,000. Message me if serious, I’ll send details and photos.”

Israa K. al-Lami, a legal expert and a professor of law at an Iraqi university, has been researching and publishing on migrant workers’ rights in Iraq since 2014. She described the commodification of migrant domestic workers in Iraq as a “deeply rooted societal issue that reflects how normalized inequality has become.”

While coercive domestic labor and human trafficking are explicitly banned under Article 9 of Iraq’s Labour Law No. 37 of 2015, al-Lami notes that “these practices remain widespread and enforcement is rare and largely symbolic.”

Legal gaps, human costs

In January 2025, the Nigerians in Diaspora Commission (NiDCOM) revealed that over 5,000 Nigerian women are stranded in Iraq, facing unsafe and uncertain conditions after being sent to work as caregivers.

“A husband sent his wife to Iraq to work as a caregiver. She’s dead,” said NiDCOM Chairperson Abike Dabiri-Erewa.

While reports summarize the abuse, the Facebook group reveals its source: employers themselves, mocking and mistreating workers openly without consequence. Casual racism is common, especially towards African workers. Members of the group treat basic human needs like shampoo or lotion like luxuries. When one worker requested healthier food and hygiene products, her employer called her “spoiled” and “demanding,” despite admitting she was otherwise a “good worker.”

In 2011, the International Labour Organization adopted Convention 189, recognizing domestic workers’ rights. Since then, over 30 countries have legislated protections. Iraq has not. Although the country ratified the 2023 International Convention on Migrant Workers’ Rights, implementation is lacking.

“Iraq has no legal framework that allows migrant domestic workers to form unions or advocacy groups,” says Khalid. “Even existing unions don’t accept foreign workers, and the issue is often framed through a nationalistic lens, prioritizing Iraqis, rather than through a rights-based perspective.”

This legal vacuum leaves migrant workers without representation or recourse. Khalid’s assessment points to a system not just indifferent to migrants, but structurally exclusionary.

The people behind the screen

Joy, who spoke under the condition of anonymity, is a Nigerian domestic worker. She was introduced to Raseef22 through a social worker from Iraq's Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. Joy left Nigeria with the promise of a job in a spa or similar establishment in Iraq but ended up as a live-in domestic worker. In Baghdad, she spends her day caring for children, cleaning and cooking from seven in the morning until midnight. Joy isn’t allowed to cook Nigerian food for herself, because her employers claim the spices in her food would ruin the kitchen’s smell. She sleeps in the same room as the children and has not had a full day off in nine months.

“My passport was taken by Baba and Mama,” Joy says, referring to her employers. Even the use of familiar titles like "baba" and "mama" reveals the kind of respect and allegiance that is expected of domestic workers, despite the dignity they are denied. “I haven’t seen it since. They allow me to keep my phone, but I know other African domestic workers who are only allowed to use theirs for one or two hours a day.”

“My passport was taken by Baba and Mama,” Joy says, referring to her employers. Even the use of familiar titles like "baba" and "mama" reveals the kind of respect and allegiance that is expected of domestic workers, despite the dignity they are denied.

Sometimes Joy’s $250 monthly salary is reduced by money transfer fees and hygiene products that her employer purchases on her behalf, most of which are unsuitable for her hair type.

“I’m lucky,” Joy said quietly, avoiding eye contact. “My employer is better than most.” For many migrant women, survival means staying silent about their abuse.

Joy is not alone. She introduced Raseef22 to Sash, a 40-year-old widow from Zambia who also spoke under the condition of anonymity. Sash has spent the last four years working in Iraq. Her day starts at eight in the morning and ends at nine in the evening. Like Joy, Sash is barred from cooking Zambian food, her employers citing similar racist sentiment. Her employer also limits her phone use to just two hours a day, which she uses to stay in touch with her family.

Sash was initially offered a salary of $400 a month, but her employers have started withholding her wages, and she now earns only $300, all of which she sends home to support her four children.

Though she has missed milestones, like her son’s graduation and her uncle’s funeral, Sash keeps working in Iraq to support her struggling family. “This is the situation I got myself into. I’m lucky to be supporting my children and family. Most of them don’t work, so I can’t complain too much.”

Like many domestic workers, Sash and Joy have accepted abuse as part and parcel of being able to provide for her family back home, highlighting the dire economic circumstances that keep the harsh migrant labor industry thriving.

Normalizing exploitation

The Facebook group is only a reflection of a wider culture of normalized abuse and racial hierarchy inside some Iraqi homes, but this casual dehumanization does not exist in a vacuum.

All over Iraq, face-whitening creams fill beauty store windows and are often the go-to product for content creators looking to secure sponsorships or launch their own beauty lines, quietly revealing the deep-rooted colorism within the country.

Afro-Iraqis have long faced discrimination rooted in the country’s history of slavery, a legacy that still shapes perceptions of race today, despite its abolishment in 1924. Young Afro-Iraqi men are often called abed, a term historically used for enslaved people of African origin across Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula. When African women enter some Iraqi households as domestic workers, they are frequently viewed through that same lens, stripped of dignity and seen as inferior.

Women with brown complexions in Iraq are often called zarka, meaning blue-faced, or jalha, meaning dark-faced; when a dark-skinned Iraqi woman marries a lighter-skinned man, it’s often referred to as “Zarka’s luck,” implying she married above her shade.

After 2003, Iraq’s middle class grew through foreign investment, reconstruction, and more government jobs. This boosted demand for affordable household help, but Iraq’s laws and cultural awareness have not kept pace. In the Facebook group, many employers justify hiring migrant domestic workers over Iraqi women, despite the risk of cultural misunderstanding or shock. Some Iraqi employers argue that local workers are less tolerant of micromanagement or mistreatment—let alone abuse, control, and classism. Such tensions can escalate into tribal disputes requiring costly settlements. Consequently, many turn to migrant workers, whom they perceive as less protected and more easily controlled.

Some Iraqi employers argue that local workers are less tolerant of micromanagement or mistreatment—let alone abuse, control, and classism. Consequently, many turn to migrant workers, whom they perceive as less protected and more easily controlled.

Generally speaking, there has been no public reaction or Iraqi media coverage on the topic of racism and abuse towards its migrant and domestic workers. The subject remains heavily underreported, with nearly all available sources published exclusively in English.

A call for justice

The first time I saw a domestic worker being mistreated or neglected, I stayed silent. I was young, uncertain, and afraid to speak up. A personal awakening alone isn’t enough. Real change requires more Iraqis to confront what happens behind closed doors. Silence, after all, is complicity. This silence isn’t just individual, it also reflects how difficult it has been, even for committed organizations, to address an issue so often hidden behind screens and veils.

Although civil society has played a vital role in advancing human rights in Iraq, migrant domestic workers have often fallen by the wayside of mainstream advocacy. This is not due to apathy, but to a combination of limited funding, shifting donor priorities, legal uncertainty, and the complexity of working on an issue often hidden behind private doors. Still, some organizations are stepping forward.

Since 2015, the Peace and Freedom Organization has made migrant labor as part of its agenda.

“We’ve engaged with lawmakers on the long-delayed Trade Union Freedom Law,” says Khalid. “A bill that, if passed, could mark a turning point for worker protections. It would align Iraq with international labor standards, particularly ILO Conventions that guarantee the right to organize, regardless of nationality or job sector.”

Even Iraq’s 2023 Social Security Law, he notes, fails to fully cover informal and migrant workers. “We need structural reform,” he says. “Not just legal patches.”

The first time I saw a domestic worker being mistreated or neglected, I stayed silent. I was young, uncertain, and afraid to speak up. A personal awakening alone isn’t enough. Real change requires more Iraqis to confront what happens behind closed doors.

The Migrant Resource Center offers free counseling, legal guidance, and multilingual assistance. In collaboration with the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, the Center empowers migrants with information on safe migration, rights, and reintegration to help them navigate migration challenges effectively. Their website also offers guidance on obtaining legal permits for migrant housekeepers, helping ensure a safe environment for both employers and workers.

For Khalid, that means recognizing the right of migrant workers to organize, ensuring their inclusion in existing union structures, and strengthening protections within private households where most abuse remains unseen, but, coincidentally, is confidently displayed on screen.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!