It’s about a decade ago when a friend in Istanbul took me to the Aziz Nesin cultural center for a cup of tea. He is a fast walker, a theater maker and an intellectual with all the proper leftist credentials. We were just passing Istiklal street when a few young guys stopped him to sell him a local communist paper, which he bought after a short discussion.

“They’re idiots, ten euros! I told them no artists or anyone from the working class will afford their paper”

“So you’re an Iranian refugee, now tell me, are you a liberal or a communist?”

I knew he was speaking about himself. In the previous days he had shown me the art of eating delicious but simple meals for very little money, going to Istanbul’s little hidden eateries

“You bought it though, why?”

“Because they still have their ideals, I don’t want them to lose hope”.

In the cultural center he ordered two fincans of tea and introduced me to the waiter as an artist who had fled Iran as a young kid. The stern waiter never smiled, but had a question ready for me:

“So you’re an Iranian refugee, now tell me, are you a liberal or a communist?”

“My father was a communist!” I told the guy. “That’s how we escaped, with his Kurdish communist contacts smuggling us over the mountains, from Iran to Turkey”

“He’s a tricky one” the waiter told my friend. “I asked him if he’s a communist, and he deflects by talking about his father!”

I wasn’t ashamed for not being able to answer his question, but I did feel like a fraud sitting in the Aziz Nesin center without having read his books. A few years before I had tried to find his books in the central library of Amsterdam. The computer told me they were available in Turkish, Persian and, curiously, in Portuguese. Not finding his work in a language I was comfortable reading, I had postponed being introduced to the works of a writer my father often talked about.

“My father was a communist!” I told the guy. “That’s how we escaped, with his Kurdish communist contacts smuggling us over the mountains, from Iran to Turkey”

Last Friday at closing time my own cultural center Mezrab was almost empty. Two young Turkish men had a beer with me at the bar. I asked them if they had heard the news.

“What news?”

Sadly it seems the fatwas of the religious fanatics live on after their deaths too.

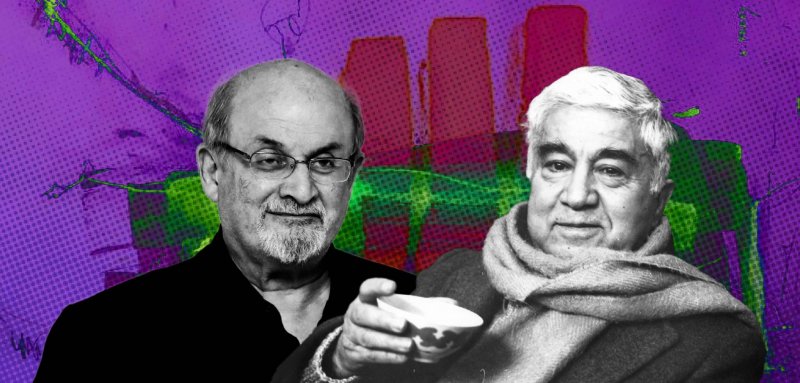

“Salman Rushdie being attacked and almost killed on stage in New York”.

The guys were young leftists, like the ones who would sell papers on Istiklal street or serve strong cups of tea in cultural centers. But they were also too young to remember Rushdie's Satanic Verses or the fatwa the Iranian Ayatollah Khomeini had spoken over him in the last year of his life.

Then I asked them if they knew who Aziz Nesin was and how he was almost killed. Of course! they replied, our most important writer. Hated for being a communist, an intellectual, an atheist, an Alevi. It was in 1993 when a frenzied crowd left the mosque in the city of Sivas to go to the hotel in which Aziz Nesin and other artists, most of the Alevi, had gathered for an event. They attacked the hotel for eight hours without the police intervening, finally managing to burn it. Thirty seven people died in the fire. Aziz Nesin, an old man then, escaped by climbing a ladder, but even when he did so the firemen who were supposed to help him recognized him and attacked him.

Rushdie hopefully will survive the barbarous attack of last weekend, even if thousands of other intellectuals in my native Iran did get killed by the same Ayatollah who issued a fatwa against him.

All that was true, but there was some context the young men didn’t know. The final cause of the anger of the religious mob towards an intellectual like Aziz Nesin had been his wish to translate and publish Rushdie’s Satanic verses in Turkish.

Aziz Nesin survived the attack, even if thirty seven others died. Rushdie hopefully will survive the barbarous attack of last weekend, even if thousands of other intellectuals in my native Iran did get killed by the same Ayatollah who issued a fatwa against him. And when one day, hopefully in old age, Rushdie dies, his complex and irreverent literature will live on, just like today the subtle poetry of Nesin does. Sadly it seems the fatwas of the religious fanatics live on after their deaths too.

رصيف22 منظمة غير ربحية. الأموال التي نجمعها من ناس رصيف، والتمويل المؤسسي، يذهبان مباشرةً إلى دعم عملنا الصحافي. نحن لا نحصل على تمويل من الشركات الكبرى، أو تمويل سياسي، ولا ننشر محتوى مدفوعاً.

لدعم صحافتنا المعنية بالشأن العام أولاً، ولتبقى صفحاتنا متاحةً لكل القرّاء، انقر هنا.