A traditional house standing defiantly amid a row of glass high-rises caught my eye. Made of soft beige stone, its three stories bore the triple arcades emblematic of Beirut’s architecture.

I climbed the staircase. A door opened, and a white-bearded man in his sixties appeared, a beret on his head. Startled, he listened as I explained my curiosity.

“Come on in,” he said. “I was just going downstairs for a coffee.”

Inside, hanging on the entrance wall, Van Gogh’s face was encircled by pistols, above military boots bearing flags of Britain, the United States, Turkey, Iran, and Russia.

The man returned. “I’m Zico, from Zico House.” The painting, he explained, came from an initiative translating political statements into visual art. I wondered what statement Van Gogh made.

As Zico spoke about what the house itself had witnessed, I recalled Elias Khoury, who described culture as “a means to remain alive in moments of chaos, wars, dreams, and nightmares.” What does it mean, he asked us, for culture to be a means to remain? I wasn’t sure.

I came of age in a Lebanon shaped by sectarian structures, fused with a neoliberal economy, and reinforced by recurring geopolitical pressures, most violently Israel’s transgressions. I contested this order through sustained engagement that periodically crystallized in moments of mass mobilization in Ras Beirut—among them the #YouStink movement in 2015, the Beirut Madinati campaign that followed, and later the October 2019 uprising, when new political languages and spaces briefly opened.

Yet these openings rarely held. Mobilization surged, then dispersed—not from lack of conviction, but because we lacked the cultural and organizational infrastructures that might have sustained it. Over time, many of us slid into political despair, losing the sense of agency needed not only to press for change, but even to imagine it. In the end, we lost the imagination to remain in Beirut.

What began as a conversation about Zico House became, for me, a lesson in political practice. Zico’s stories traced a generation that weaponized culture as political leverage: building spaces, sustaining networks, and organizing collective work through which people could speak, coordinate, imagine alternatives, and pressure power during and after the civil war.

Kriza

Built in 1935 during the French Mandate, Zico House witnessed aspirations for liberation from colonial rule.

Emancipation was imagined not through imitation of the West, but through efforts to fuse contemporary ideas with local continuity taking shape across Pan-Arabism, Lebanese nationalism, and socialist anti-imperialism.

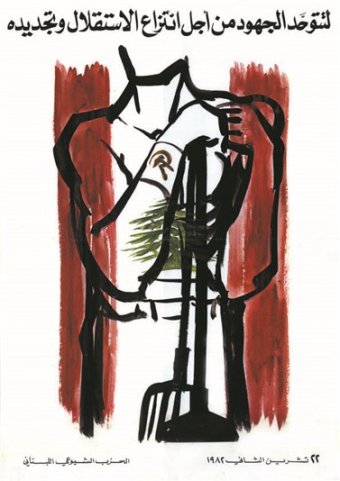

Political debates found expression in print, radio, theater, poetry, and the visual arts through figures such as playwright Edward al-Dahdah and singer Omar al-Za’ani, whose songs mocked the French authorities and cost him his post. Cultural production reached beyond elites, permeating public life, translating political critique into shared popular language, and priming collective action.

When the French arrested President Bechara El Khoury and Prime Minister Riad El Solh for seeking to remove references to the mandate from the constitution, the city erupted in major protests. The social upheaval eventually led to their release on November 22, 1943—Lebanon’s Independence Day.

Omar al-Za’ani’s lyrics in Kriza poke fun of a world in turmoil in contrast with the displays of wealth on the streets.

“It was the rare image of a country in transition that succeeded, even if just for a moment, in overcoming its differences,” wrote Samir Kassir in his seminal book on the capital, “Beirut.” Kassir, a notable Lebanese historian and public intellectual, was assassinated in 2005.

Not long after the country’s independence, the house had to resist another tide as Beirut expanded chaotically, best described by L’Orient as “a monstrous jumble of architecture.”

Over time, many of us slid into political despair, losing the sense of agency needed not only to press for change, but even to imagine it. In the end, we lost the imagination to remain in Beirut.

That tide stemmed from emancipation hardening into regimes where local elites replaced colonial authority, inaugurating a laissez-faire model that ceded urban growth to private developers and subordinated public need to profit.

I had long understood this period as divided between crisis and cultural vitality; what became clear to me at the time of writing was that these were not competing narratives. It was the crisis that ignited cultural vitality. Student protests, labor strikes, a proliferation of magazines, an oppositional press, and experimental theater turned culture into a space of dissent and imagination. Artists and activists manipulated the climate to confront political rupture and search for new horizons.

By the 1960s and 70s, when Zico came of age, Beirut was shaped less by civic vision than by market forces, its inequalities and fragile governance laid bare by the 1958 war and the shock of the 1967 defeat (Naksa). Lebanese theater turned decisively toward politics and social critique, moving beyond imitation to reflect local realities and cultivate distinct voices. Cultural producers forged a shared visual and political lexicon, one that sought to weave resistance into everyday life.

In his 1970 essay, “Towards a Revolutionary Arab Art,” Kamal Boullata, the Palestinian artist and intellectual, described this moment as one in which artists were transformed from observers into political actors.

“Artists who used to look from the window of their studio were no longer seen there because they came down to the street,” Boullata observed. “Posters were everywhere, yet their creators remained anonymous; poetry appeared on some yet the poet’s name remained unknown.”

The essay appeared in the Beirut-based journal Mawaqif, a self-funded space of questioning sustained by voluntary labor, modest subscriptions, and Beirut’s intellectual networks. Such cultural production was sustained at the grassroots through collective labor, self-organized spaces, community committees, and the infrastructures of political movements that pooled resources and volunteered time.

Zico emerged from this very ecosystem. His parents were active members of the Lebanese Communist Party—by then a major cultural and intellectual force—and he joined its youth wing, Ittihad al-Shabab al-Dimuqrati (Democratic Youth Union), when political action was a disciplined commitment shaped by political education. He considered cultural work inherent to political life.

Kassir traced this vitalized energy to a broader search for new forms of expression and an unfinished process of political renewal. He demonstrated how this appetite for change found its most vivid expression in culture, using Maroun Baghdadi’s film, “Beyrouth ya Beyrouth,” to reveal social and political realities often overlooked by conventional history.

Historian Fawwaz Traboulsi, in the documentary “Maroun Returns to Beirut,” highlighted the same film for exposing the deeper realities of its time and dismantling the myth of a “golden age,” asking pointedly: “How can a golden age lead to a civil war?”

Bennesbeh labokra chou?

Born after the Civil War and raised amid its silences, I imagined the war only as violent chaos: a city without people, sinking into dust and darkness, its civilian life collapsed. It was only years later—through conversations with Zico and while writing this piece—that I discovered that this image was incomplete: despite the violence, the impulse to resist social and political paralysis had endured.

Zico’s recollections reveal a people determined to reclaim agency amid chaos. As escalating violence and militia repression narrowed the space for direct mobilization, people turned to cultural production as a way to act: confronting the war directly, shaping how it was lived and understood, and asserting collective presence within a fragmented landscape.

Lebanese theater turned decisively toward politics and social critique, moving beyond imitation to reflect local realities and cultivate distinct voices. Cultural producers forged a shared visual and political lexicon, one that sought to weave resistance into everyday life.

Beirut’s walls and print presses teemed with posters and magazines weaving resistance into everyday life. The Hakawati Troupe, co-founded by director and playwright Roger Assaf in 1977, staged plays reflecting popular grievances and embraced crowd work, involving the audience in both content and performance.

Assaf explained that their theater was entirely collective, with members sharing responsibilities and revenues equally. Rooted in everyday life—neighborhoods, families, villages, and memory—even practical needs like lighting and venues were resolved collectively. For him, Hakawati was less about theater as art than about political commitment, grounded in the lived realities and ideologies of its time.

Hanane Hajj Ali, who joined Assaf in 1978, underscored theater’s power to restore agency at that time, writing: “[the theater] brings me back to my deepest truth, to my history, to my identity… as a force of resistance in the face of the war.”

Meanwhile, artists harnessed music and theater to challenge dominant narratives. Ziad Rahbani, Marcel Khalife, and Ahmad Kaabour turned performances into visions of solidarity and change. Filmmakers like Baghdadi, Jocelyne Saab, and Borhane Alaouié moved beyond nationalistic storytelling, common before the war, toward politically charged narratives, capturing the war’s emotional, social, and political dimensions. In a 2017 interview, Saab recalled the Israeli invasion of 1982, when she and some 70 artists chose to remain in Beirut—because staying was itself a conscious act of commitment, a decision to defend a cause.

Writers like Elias Khoury, Hassan Daoud, Rachid al-Daif, and Rabih Jaber chronicled violence through intimate narratives that reflected the everyday experiences of those living through the conflict. In 2022, Khoury observed that the war “liberated literature,” shifting it from nostalgic poetry detached from the present to “the opportunity to destroy the dominant language and open the literary scene to what I call ‘writing the present.’”

Traboulsi later underscored the value of this cultural production: “The great service that was done to any history of Lebanon was the fact that the war itself produced an enormous amount of historical, economic, political, cultural, sociological production.”

Arming ourselves with collectivism's duties

In the 1990s, Zico House survived yet another transformation.

Post-war reconstruction, driven by neoliberal logic and foreign capital, demolished historic neighborhoods and imposed a sanitized vision that erased Beirut’s architectural and cultural cores. Kassir denounced this urban amnesia, warning that it erased the imaginaries needed for collective reckoning. It was in this iteration of Beirut—where our memory was systematically overwritten—that I grew up.

Yet the erasure of our imaginaries did not go uncontested. As postwar sectarianism narrowed formal avenues for organizing, Beirut’s cultural landscape became a vibrant, if precarious, arena for contestation.

This moment, as Ziad Majed noted, called for remembering “the efforts, the joy, and the wonder it held.”

That same joy animated Zico’s voice as he recalled the period. For him, culture was not an escape from politics but a way to generate ideas, spur political engagement, and challenge dominant narratives. His commitment mirrored broader efforts to revive Beirut’s cultural life, from Théâtre de Beyrouth to al-Madina Theatre. Amid censorship, he believed in independent spaces where artists and activists could gather freely.

After his father’s passing, he opened the house to civic life: “Zico House became a hub for the birth of ideas. We nurtured them until they became associations or collectives, then let them grow.”

Groups began in a single room before expanding outward, turning the house into a space for alliances and civic struggle often absent from Lebanon’s politics. In 1997, when Paul Ashkar proposed a campaign for long-overdue municipal elections, the first since 1963, Zico opened his doors to the idea. The “Gathering for the Holding of Municipal Elections” was born, driven by grassroots energy and creative tactics like Ziad Rahbani’s “Baladi, Baldati, Baladiyati” jingle, which aired across TV and radio to rally public support. Seminars, petitions, and protests followed; over 100,000 signatures were faxed daily to the presidential palace.

“I sent twenty pages each morning from Zico House, only to find them returned by evening,” Zico laughed. But he and his comrades persisted, and within a year, the government announced municipal elections.

Culture and civic life, Zico believed, could challenge the dominance of money and model different ways of rebuilding. Revitalizing public space and embedding culture in the city were central to reclaiming Beirut from the grip of privatization. He advanced this vision by starting the Beirut Street Festival, which infuses Beirut’s neighborhoods with artistic energy and collective celebration during the summer since 2002.

By the time I entered university in the early 2010s, I was stepping into a city reshaped by reconstruction, its city center stripped of memory and devoid of any public reckoning with the civil war. What remained of these earlier efforts reached me not as a coherent movement or shared project, but as fragments. Hope, and the sense that people could still enact change, was still present.

I joined campaigns for civil personal status laws, mobilizations against the extension of Parliament’s mandate, efforts to defend historic houses like the Red House in Hamra, and initiatives supporting the families of the disappeared. It did not take long to feel how dispersed these struggles had become, and how difficult it was to sustain the collective momentum that earlier generations had worked so deliberately to build.

“Change begins with volunteering,” Zico told me. “We gave our time to achieve change.”

The postwar neoliberal model reshaped dissent. Aid poured into civil society, NGOs multiplied, and political engagement was increasingly channeled through donor-driven frameworks. Civic engagement shifted to donor-driven projects as grassroots political organizing declined. What had been collective and participatory became professionalized project-based work, as grassroots organizing thinned.

Revitalizing public space and embedding culture in the city were central to reclaiming Beirut from the grip of privatization.

“Funding created a new system. People only want to work if there’s money,” Zico said. “Now it’s mostly employees. You rarely see people protesting outside of their jobs.”

While new funding structures, such as the creation of the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) in 2007, offered support for cultural production, they also reflected the broader professionalization of collective work and civic duty.

“We didn’t have money [back then]. We had ideas that took shape through collaboration.” Cultural and civic work, he explained, “was attractive. We weren’t chasing after NGOs to earn a salary in foreign currency.”

Khoury similarly remarked how market forces, together with academic institutions, tamed their voices by commodifying their research and promoting the image of the “objective” intellectual detached from struggle. In doing so, they undermined the intellectual’s role as an agent of justice and freedom.

Kassir had already diagnosed the city’s paralysis in the early 2000s, warning that Beirut was being remade as a site of leisure for elites rather than a space of intellectual defiance and civic engagement. Both he and Khoury cautioned against a withdrawalist culture, one that watches without witnessing, describes without intervening, and submits to market logic without critique.

But Zico refused this retreat. He spoke of rebuilding networks for civil society, reviving volunteering, and creating new tools: digital platforms, magazines, and forums. These forums would recover a shared civic culture, much like Khoury’s Mulhaq al-Nahar once did.

“What matters,” he said as I left, “is to always be active,” reiterating Kassir’s prescription:

إحباط لن يزول إلا بالحركة، الحركة الواضحة التي تعيد رسم الرهانات في أولوياتها

“Frustration will not vanish except through movement—clear movement that redraws priorities.”

Beirut, my city

Looking at and living in Beirut today, I am troubled by the direction in which the city is drifting: a future increasingly shaped without those who must endure it, leaving us sidelined in determining what Beirut, and Lebanon more broadly, will become.

How do we cultivate a culture that bears witness to lived realities and gives them voice? A culture that can turn spontaneous eruptions into a coherent vision of the world from below? One that, even at the height of despair and disillusionment, insists on other possibilities and potentials and refuses domination and erasure? And what models might move us beyond NGO-ization and professionalization toward genuine grassroots collective efforts?

Lebanon in the past year grieved the loss of Elias Khoury and Ziad Rahbani, and many of us could not help but feel as though we were also mourning a time of cultural vitality, when we ascribed power to our voices, which disseminated popular grievances, validated our experiences, and challenged dominant narratives in ways that resonated profoundly and permanently.

Civic engagement shifted to donor-driven projects as grassroots political organizing declined.

For many of us, the earlier days of the 2019 Uprising revived a shared hope we thought we had lost. Yet years of depoliticization and NGO-ization had hollowed out the structures and imaginaries needed to sustain it. The histories traced through Zico House can show us how earlier generations—even when they failed to secure lasting political change—retained a sense of possibility that now feels fragile.

In 1968, when security forces banned Assaf’s play “Majdaloun” for criticizing the state’s stance toward Palestinian resistance, the troupe defied the ban by relocating the performance to the Horseshoe Café, where they continued in front of a live audience. How do we rekindle this spirit of cultural defiance today?

Searching for a response to any of the questions posed above will require Sisyphean effort from all of ust—but persistence and insistence are all we have left to keep our agency from being completely erased.

When I finally stepped back outside, surrounded by Beirut’s blue skies and neoliberalism’s glass towers, Zico House appeared less of a relic than historical evidence of something we’ve forgotten: that collective political life does not emerge spontaneously—it is made. By turning to our earlier struggles in Lebanon, we can examine how that work was once done. Otherwise, we may well lose not only our political direction, but the collective practices that once imagined and shaped our future.

Translating politics into art was only part of a much larger task: cultivating a culture grounded in people’s everyday social and material conditions—one capable of turning lived constraints into shared political consciousness and, from there, into visions of emancipation.

As Khoury once wrote: “Beirut has not died, but it is dying. We can retrieve [it] through cultural work, because such recovery carries within it the possibility of new Arab beginnings.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!