Yasmine, a housewife, discovered her husband’s infidelity after he cheated on her with her only friend, which prompted her to ask him for a divorce after a marriage that lasted for about 20 years. The husband, Rafaat, agreed to the divorce, on the condition that he only gives her the deferred dower (only part of the dowry), which was only a thousand Egyptian pounds, leaving the 40-year-old woman out on the street after she left her only home, with no shelter or livelihood that would spare her the embarrassment and humiliation she underwent and ensure her some semblance of safety.

This is one of the stories that was featured on the TV series “Ella Ana”, which focuses on presenting various social issues in Egyptian reality, especially those that women encounter in their daily struggle. It provides a reflection of the conditions of thousands of Egyptian women who limit themselves to the role of a housewife without an independent source of income, and then suddenly find themselves without income or shelter when a divorce takes place.

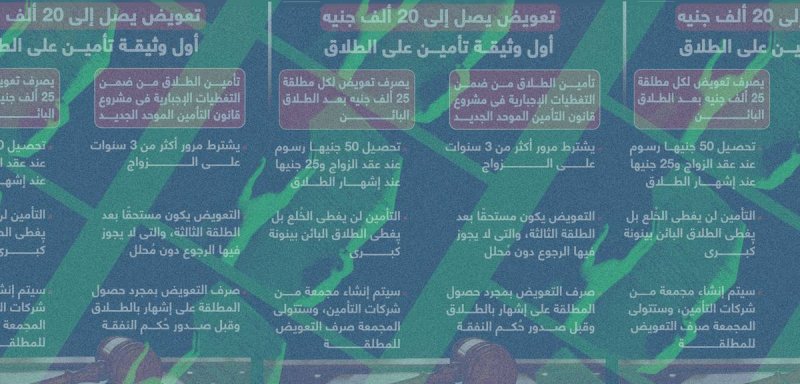

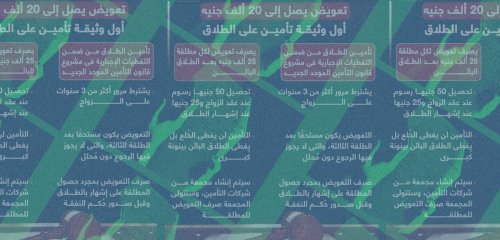

The recurrence of such cases in the absence of any legal texts that guarantee women a decent life after divorce — especially if they had a divorce after having missed out on job opportunities and the ability to gain experience, in a limited labor market that suffers from crises and inequality — have all prompted Egyptian feminist voices to call for the establishment of a law that secures women’s lives upon divorce. In accordance with these demands, the Financial Regulatory Authority prepared a preliminary study on Article 39 of the new unified insurance draft bill. According to the bill, (if Parliament approves it), a divorce insurance policy will be issued, under which women will be given 25 thousand Egyptian pounds (1,370 dollars) in the event of divorce.

The law does not guarantee women a decent life after divorce, especially if they had a divorce having missed out on job opportunities, in Egypt’s tight labor market

In the wind

Yasmine’s story is but a real example of women who suddenly found themselves without any income or life opportunities after divorce. Some of them had gotten married and left work, while others had to yield to their husbands’ stipulation that they leave work after marriage.

Shorouk Hussein is one of these women. She tells Raseef22 that before they got married, her ex-husband stipulated that she not work, but after the divorce, good job opportunities were very limited, if any were even found. Her current salary does not even begin to meet the costs of the basic needs of her and her daughter. “It was a very difficult period without any income or any work,” she says. “I decided to enroll in English language courses that would pave the way for me towards hope at a time when I had no skills.”

In light of the escalation of human rights demands to share wealth between spouses in the event of divorce, Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb, the Grand Imam of al-Azhar, revealed what’s called “the right of toil and pursuit”, which would give the Egyptian woman a share in her husband’s wealth, provided that she has contributed to the formation of that wealth through direct work with the husband and by participating in his trade or business. This comes in line with long-established societal considerations that do not view domestic work done by women as a “job” or “work” that is worth pay, and do not consider it within the conventional distribution of gender roles as a contribution to the development of the family’s wealth, by exempting the husband from domestic tasks and raising the children in return for spending his energy in making money.

Shorouk Hussein is one of thousands of women whose husband stipulated before they got married that they not work. But after the divorce, good job opportunities were limited; her salary does not even begin to meet her basic needs

According to a study by Alternative Policy Solutions (an independent research project in economic and social policies), Egyptian women spend 34.3 hours per week on housework. And if they are employed workers, they work another 36.4 hours per week outside their homes on top of these hours. This makes the number of hours of unpaid domestic work (pure physical labour) equal to the total number of hours of paid work outside the home.

After the divorce, Shorouk Hussein suddenly found herself without any income or savings because her husband had prevented her from working. She believes that the financial value of the insurance policy within the draft law is “very weak in light of the economic burdens that we live in today, and the cost of living can come to this amount within two or three months.” Hussein suggests that the state should pay more attention to rehabilitating divorced women for the labor market, and helping them find job opportunities without any fees.

Among the conditions of the policy: the marriage lasted 3 years, and that divorce had been done twice by an authorized person during the marriage. In addition, a divorced woman is not entitled to the premium if she initiated the divorce

“I didn’t have enough money for transportation to go back to my parents’ house.” With this phrase, Mona Darwish began her story, recounting to Raseef22 her first moments after the divorce. The very first thought that came to her mind was: ‘How can I find a job that guarantees me and my son a decent life without having any experience?’.

Darwish was lucky enough to find a job close to her family’s home, “Actually, the job position had been for my sister, but she told me, ‘the priority is to you, go in my place’.” However, the work only offered a modest wage that does not ensure her son the future she dreams of for him, but it does cover their basic needs.

Darwish does not see that the document’s value is enough to help divorced women start over, especially with many husbands evading their responsibilities to provide financial support for their children after divorce, while divorced women end up bearing the costs alone in many cases. She believes that divorced women need a strict law that punishes fathers who shirk their responsibilities towards their children and child support, leaving the wife stuck in the vortex of litigation, attempting to provide proof of the husband’s income in order to obtain “alimony”.

The family of Samar Madbouly, the founder of an association that develops talents for economic development, refused to let her work after her divorce because of the divorce itself. “My family refused that I work because I can’t go out and work while I’m divorced, because of the way people will look at me.” With the need for a source of income, Madbouly resorted to working from home. She found her calling in making handicrafts that she would put up for sale in nearby shops.

Samar does not trust that any decision in favor of divorced women will pass through Parliament, and despite the fact that the amount within the divorce insurance policy is “modest”, she expects it to be met with strong opposition. Samar’s projections come from the broad experience she acquired while working. She decided to create opportunities for other divorced women who found themselves without any job or income after divorce, by establishing “Mawaheb for Economic Development”, an organization that trains divorced women and widows in handiwork and establishes small businesses without receiving support from any institutions, whether governmental or independent.

Egyptian women spend 34.3 hours per week on housework. If they're employed, they work another 36.4 hours per week outside their homes, making the number of hours of unpaid domestic work equal to the total number of hours of paid work outside the home

Salwa Bassiouni’s reliance on her own work has created a “great barrier” for her against the psychological and economic obstacles that many divorced women face. Bassiouni says, “I found myself suddenly fully responsible for my daughter and her expenses after the divorce, because the father is of course stubbornly refusing to spend any money or sometimes provides very little expenses that do not meet the girl’s needs.” Bassiouni believes that the value of the insurance policy against divorce is “not enough to guarantee a decent life for a divorced woman.” She clarifies, “Life is very difficult. Food, drink, clothes, medical bills, and the children’s expenses are all things that the father is always trying to use in order to put pressure on the mother. In most cases he uses them to punish her financially because she had asked for a divorce and insisted on it. An amount of 25 thousand pounds may cover these expenses for a few months, no more.”

Legal obstacles

Noha al-Sadek, a former lawyer and owner of the “Faseekh Beity” project, separated from her husband, leaving her with two young children. She relies on her work to support herself and her daughters, “I was working before the divorce, and this could be the reason that made it easier for me to make the decision to end a life I didn’t like.” Speaking to Raseef22, she says, “Living conditions have become difficult nowadays, and the amount stipulated in the divorce insurance policy cannot guarantee a decent life for a divorced woman.”

By virtue of her legal experiences, al-Sadek took note of the conditions set by the state to obtain the amount specified in the document. She criticized the conditions which stipulate that the divorce must be “a major irrevocable divorce”, meaning that the marriage lasted 3 years, and that the divorce had previously taken place twice and was done by an authorized person during the marriage period, “in addition to the fact that a divorced woman is not entitled to this grant in the event she had officially requested divorce.”

Al-Sadek believes that the draft bill includes “many legal loopholes” that prevent divorced women from benefiting from this legal document, which prompts her to ask the question: “What would a woman do if she is suffering with her husband and he refuses divorce? What would a woman do if she had only been divorced once and it was impossible for her to go back and live with her ex-husband?”

Repairing what society ruined

Writer and feminist activist Amal Ewida comments on the divorce insurance policy bill, saying that the presence of compensation for women in case of divorce is “a good step that should be encouraged and welcomed”, indicating that this draft would not have been put forward if it had not been for calls and demands made by women. She pointed out that “passing a draft like this one will take a lot of time,” and requires pressure from both the human rights and feminist communities, in addition to official demands made by female parliamentarians to push for the implementation of the bill, “so that it won’t just remain under consideration, but so that it becomes an applicable law in force.” She called on jurists to hold workshops aimed at achieving an acceptable formulation of the proposed draft, and to study it on every aspect “in light of the current economic conditions, and its future implications for the next several years since the value of 25 thousand pounds may equal very little later on. It is better to have another alternative here that guarantees a decent life for the divorced woman, such as a clause stipulating that 50% of the husband’s monthly salary be given to the wife for at least three years.”

Ewida asserts that a female’s education and work is “not a luxury” because many women separate from their husbands and end up with no income. Some men are intimidated by a woman working, especially if the work guarantees her an independent life far from their control and authority. She also believes that the drafts aiming to improve the conditions of divorced women in Egypt are an attempt to fix what society has corrupted.

Women’s lost rights

Michael Raouf, a lawyer specializing in women’s issues, and a member of the Nadeem Center for the Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence and Torture, believes that the proposed legal article for the document “needs review”. He suggests that to improve the conditions of divorced women, “special attention must be paid to Nasser Social Bank (NSB), which supervises the payment of the pensions of divorced women”. In addition, the maximum amount of expenditure must be raised from 500 pounds to at least 5,000 pounds, which, according to him, would be enough for a woman to spend on “eating and drinking only” after her divorce, especially in light of rising inflation, rising prices, and the decline of the purchasing value of the Egyptian pound. He explains, “The state can set strict laws for the implementation of expenses and can supervise the implementation process with ease.”

Amira AbulEzz, a lawyer at the High Court of Appeal and State Council, says that giving compensation to a divorced woman will benefit her at the beginning of the divorce and will help her overcome part of the suffering she is facing, but it will not guarantee her the security she needs, since it is a small amount. It is suitable for a temporary period “during which she would make a plan to follow in order to draw out a new life path for herself.” She believes that the process of closing the gaps that prevent all divorced women from benefiting from the document can be discussed and amended following the official legalization, especially since there are laws that have been amended after legislation, like what had been done with the family law.

AbulEzz calls for the necessity of implementing the division of wealth between spouses, and tied her demand to what she sees as “the suffering that the Egyptian woman is subjected to, and her sharing of financial burdens with the man,” which makes her end up spending her salary on home expenses or saving it with her husband, in addition to taking on all the household duties. And “when the separation takes place, the man takes all the wealth for himself after he has created it with his wife, and she ends up without anything.”

On the other hand, lawyer Wafaa' Alwan, a member of the Arab Lawyers Union (ALU), has fears regarding Article 39 of the Insurance Law that’s related to the document. She believes that “allowing all divorced women to benefit from this grant could be seen as something that encourages divorce.” She adds, “In my opinion, other cases that deserve (this document), even if the divorce happened once, should be limited to cases where the divorced woman is severely ill or supports a child with special needs, so that she would be able to take care of things financially.”

Alwan sees that the division of wealth between spouses in the event of divorce must be conditional on financial cooperation with the wife, so that she would have the right to take half of her husband’s wealth. At the same time, she sees that if the wife is without work and her role was limited to raising the children and carrying out marital duties, then she has no right to share wealth with the husband. As for “the right of toil and pursuit”, it is, according to Alwan, “An acknowledgment of the right of one party to the money of the other party who had assisted the first financially or through efforts and hard work to develop those funds, and the amount shouldn’t be worth half of the husband’s wealth, but rather the amount of money that the wife had added, the value of its profits, and the value of her efforts and hard work, and she may give up some or all of her possessions.”

Muhamad Hamada, a lawyer specializing in cases of violence against women, agrees with her. Speaking to Raseef22, he says that the draft of the divorce insurance policy will widen the scope of “divorce by mutual agreement between spouses,” meaning that it will open up new ways for fraud or for men to pressure women to seize the amount given to them within the divorce settlement. The lawyer asserts that “many family cases are subject to bargaining to make the divorce take place, especially when the wife is insisting on the divorce, which leads her to bear a great burden.” He stated that in one of the cases, a woman wishing to divorce her husband was forced to sign that she had received all her rights and alimony for her and her children on paper, but in reality had not received any of those funds.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!

Join the Conversation

ذوالفقار عباس -

1 hour agoا

Hossam Sami -

2 hours agoصعود "أحزاب اليمين" نتيجة طبيعية جداً لرفض البعض; وعددهم ليس بالقليل أبداً. لفكرة الإندماج بل...

Anonymous user -

1 day agoرائع و عظيم ..

جيسيكا ملو فالنتاين -

5 days agoزاوية الموضوع لطيفة وتستحق التفكير إلا أنك حجبت عن المرأة أدوارا مهمة تلعبها في العائلة والمجتمع...

Bosaina Sharba -

1 week agoحلو الAudio

شكرا لالكن

رومان حداد -

1 week agoالتحليل عميق، رغم بساطته، شفاف كروح وممتلء كعقل، سأشاهد الفيلم ولكن ما أخشاه أن يكون التحليل أعمق...