Despite operating out of different stations in the Arabian Gulf, the hub of the Gulf’s slave trade was Oman.

In his book ‘Britain and the Persian Gulf. 1795-1880’ (translated to Arabic by Mohammad Amin Abdullah), John Kelly provides that most of the slaves imported to Oman were sold within the country, while a few ended up in the hands of pirate traders operating along the coasts of Qatar to Oman on the Arabian Gulf.

Moreover, the al-Qawasims, an established tribe in Ras al Khaimah, Sharjah and Bandar Lengeh, were prominent slave traders who bought slaves and sold them along the same coastal areas or in the markets of Persia, Iraq, Bahrain, Kuwait and Najd.

From the two ports of Muscat and Sur in Oman slaves were transported towards the ports of “Kathiawar” in Sindh (a province in present-day Pakistan) and to the Indian province of Bombay (present-day Mumbai).

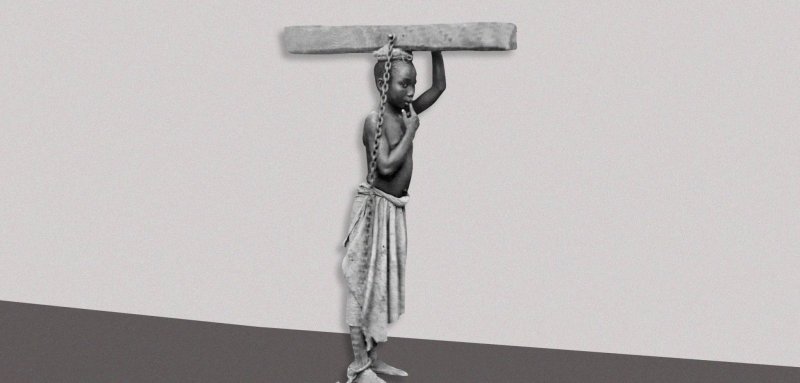

Abyssinians (‘Ḥabashīs’) In High Demand

The slave trade season often peaked around the harvest of dates in Basra. As of early June/July, ships coming from the lower Gulf area would begin their annual journey from Oman and Muscat, to the Shatt al-Arab River region in Iraq on occasion of the harvest season, stopping on a number of ports along the way to unload their shipments of slaves.

After docking, the ships would unload the enslaved ‘cargo’ in Sharjah, Ras al Khaimah, Lengeh, and the port of Bushehr, not to mention Kuwait and Bahrain’s shares of the cut. Meanwhile, slaves headed to the eastern area of the Arabian Peninsula would be delivered to the port of Al-Qatif. The accumulating profit and sums raised from these deals were generally spent on purchasing dates from Basra for consumption in the Sahel region or for selling in Muscat.

Although East Africa had long been a prime source of manpower for the slave trade, widespread exploitation of this land officially commenced in the late 17th century with Oman’s occupation of the regions of Zanzibar and the Green Island (also known as Pemba Island).

Kelly adds that under the control of the Ya'rubid dynasty (1624-1742) and later the Yemeni ruling house of Al Bu Said (1744-1964), Zanzibar transformed/turned into an established slave market - growing to become the largest center for slave trade in the East under the rule of Sayyid Said Bin Sultan (1791-1856).

Kelly notes that enslaved men and women would be rounded up from the innermost regions of east Africa: from the far west on the banks of Lake Nyasa (in present-day Malawi) in east Africa, and Tanganyika (now split among the nations of Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania and Zambia) in the center of the continent. They would then be shipped to Zanzibar to be sold there, whether to work on the plantations of Arabs residing on the island, or to slave traders heading further north.

Every year, with seasonal winds of November blowing from the northeast, Arab ships of the north begin to arrive at the port of Zanzibar to load its shipment of enslaved Africans. They promptly sail to make it back north before the peak of seasonal northwestern winds arrive to the western shores of the Indian Ocean in April or May.

During the first years of the 19th century, slaves were rarely brought to the Arabian Peninsula via the Red Sea. Ships would head out from the Yemeni ports of Hadhramaut to make their annual journey to Zanzibar, where they would stock up on slaves to sell back in the ports of al-Mukalla, Mocha and al-Hudaydah.

Slave trade in the Gulf in the 19th century was the facet of a raging colonial struggle. Along what lines was slave trade in the Arabian Gulf established? And what role did the French and the British play before the intervention of the Portuguese?

Slave traders of the Red Sea would usually set sail to Zanzibar during the fall season, making it back home before seasonal northeastern winds – or around the time Gulf slave traders would embark on their annual journeys to Zanzibar.

According to Kelly, ‘Ḥabashī’ (‘Abyssinian’ or east African) slaves were more popular and sold for higher prices compared to other Africans due to their purported intelligence and physical appeal. Most of these slaves were captured during the wars waged by the ‘Sultanate of Shewa’ (the oldest sultanate of al-Habash established by the Arab nomadic tribe of Bani Makhzum in 896, before collapsing at the hands of the Sultanate of Ifat in 1289) against the ‘Gullah’ people (ethnic tribes that converted to Islam) along the Ḥabashī borders.

Ḥabashī slaves were often sold to Gulf traders in the Somali seaport of Berbera, where an annual slave market was held between the months of October and April of the following year.

Colonial Struggle

This trade was one aspect of a raging colonial struggle among world powers hoping to gain control of the area.

In his study “British Influence and Slave Trade in the Arabian Gulf in the 19th Century”, Jasim Mohammed Shatab shows that Britain was highly protective of the area spanning the Arabian Gulf, the Arab Sea, and the Indian Ocean, considering the strategic access it offers to India. Britain was, therefore, adamant about fighting any other foreign influence in the area. It masked this presence under the guise of curtailing the slave trade the Arabs had become local suppliers of for French dealers.

One French dealer in east Africa, named Maurice, had called on his government to set up a French colony in the island of Kilwa (pertaining to present-day Tanzania). This colony would serve as a center to round up slaves and export them to work on other French colonies. Britain caught wind of Maurice’s proposition and alarm sirens went off within the corridors of the British House of Commons during the year of 1807. The debacle took a side seat in 1810, however, when France lost Mauritius to the Brits during their war against Napoleon Bonaparte. According to Shatab, this loss negatively impacted the slave trade movement from east Africa and through the Indian Ocean.

When Britain decided to abolish the slave trade in the Indian Ocean, it delegated the task to the British-Indian government in Bombay. The government took to installing anti-slave trade measures throughout the Gulf. On March 3rd, 1812, the British-Indian government of Bombay officially notified the sultan of Muscat and Zanzibar, Sayyid Said bin Sultan (1806-1856), of the new anti-slave laws, and in 1814, the ban was put into action by the British government in Mauritius. Subsequently, slavery was officially abolished from all British colonies in 1839.

The official recognition of slave trade in the Arabian Gulf came in the General Maritime Treaty signed in Ras al Khaimah in 1820. The treaty was reached following Britain’s military operations against the al Qawasim tribes in 1819

The first official recognition of slave trade in the Gulf area came in the General Maritime Treaty (the constant peace treaty) signed in Ras al Khaimah in 1820. The treaty was reached after Britain’s military operations against the al Qawasim tribes in 1819 and 1820. The 9th article of the treaty overtly stated that abducting slaves from east African shores, or from any other place, would constitute larceny and piracy. Yet, no article of the agreement outlawed the ownership, selling, or buying of slaves. Additionally, no attempts were made by the British government to specify the punishment of violating the anti-slave trade law, according to Shatab.

This was followed by a pledge imposed by British Admiral Fairfax Moresby, captain of the royal ship “Minai”, on Sayyid Said bin Sultan, Britain’s ally and sultan of Muscat and Zanzibar, in 1822, all under the instructions of Governor of Mauritius Sir Robert Farquhar.

The pledge banned subjects of the sultan from selling slaves to subjects of Christian countries. Henceforth, several treaties were adopted with the purported objective of restricting the slave trade and strengthening British hegemony over the area, without once openly outlawing the trade altogether.

Heading Further Away Towards Sur

The second half of the nineteenth century was marked by heavy French activity in search of slaves to own and trade, especially in light of the growing need for labor power in their tropical colonies. According to Shatab, these colonies, spanning the Congo River to the Sahara (now encompassing four countries: Central African Republic, Chad, Congo, and the Gabon), pit France in the face of Britain.

In 1847, a British politician residing in the Arabian Gulf and by the name of Samuel Hennell (1838-1852) drafted a new agreement with a firmer and more concise stance on slave trade than its predecessors. He obligated the ruler of Ras al Khaimah and al Sharjah Saqr bin Sultan al Qasimi, then-ruler of Dubai Sheikh Maktoum Bin Butti, the head of the Ajman province Abdelaziz bin Rashid Al Nuaimi the first, and the ruler of Umm Al Quwain Sheikh Abdullah bin Rashid, as well as then-leader of Abu Dhabi Sheikh Said bin Tahnoon to sign the treaty that officially banned slave trade and gave British vessels the right to search ships (that were) deemed in violation of this clause.

British efforts to abolish slave trade in Muscat and the Gulf’s sultanates drove slave dealers to the port of Sur (about 150 kilometers away from Muscat). Far from the prying eye of British vessels and under the radar of Sayyid Said, who ruled it remotely from faraway Zanzibar, slave trade continued in the seaside city of Sur.

According to Shatab, slaves were moved inland from Sur, reaching anywhere from the Arabian Peninsula to the sultanates of the pirates’ coast or to Bajjah.

Despite the many treaties enforced by the British, the sheikhs of the area were never serious about ending a slave trade that proved financially rewarding for them. Whether through the “transit” taxes placed on ships moving the slaves or by the financial revenue from price discrepancies in different areas, and even through the positive impact the slaves’ labor had on the economic wheel, slave trade was an important source of profit for the sheikhs. The slaves would be utilized for agricultural avenues like watering and farming, as well as in sea activities like hunting and deep diving for pearls, not to mention as fighters for military purposes.

Moreover, Britain itself was not serious about curtailing the slave trade. In an area of sparse resources, the lands’ rulers weren’t expected to abolish the slave trade if their losses for adhering to the anti-slave treaties were not reimbursed. Additionally, with only seven ships deployed to monitor and quash slave trade in the open waters spanning the coasts of east Africa to the shores of the West Indian subcontinent, passing through several gulfs and archipelagos, British efforts seem not truly committed.

Britain itself was not serious about curtailing the slave trade. In an area of sparse resources, the lands’ rulers weren’t expected to abolish the slave trade if their losses for adhering to the anti-slave treaties were not reimbursed

Furthermore, although the smaller emirates agreed to British search measures and succumbed to them, the relatively larger countries -like Persia and the Ottoman Empire- resisted British intrusion for what it carried in terms of violating the nations’ sovereignty.

Persistence of French Protection Of The Ships

Simultaneously, France was still invested in the slave trade. Not only would the French distribute their flags to and pledge protection of the ships, but they were also seasoned slave traders themselves. Under the guise of what came to be known as the “free laborers” system, over 25,000 slaves were imported to France’s equatorial colonies. The system was adopted in 1848 after France outlawed slavery in its colonies, driving Britain to intervene. The British government sent its High Commissioner in South Africa, Bartle Frere, to the slave trade central of Zanzibar in an effort to urge its ruler Barghash bin Said to outlaw the trade. The British naval seal also set an embargo around the island.

On the 14th of March 1873, Frere managed to pull an agreement out of Sultan Barghash bin Said, stating he would ban slave trading between the island and other countries. Zanzibar would shut its markets to slave dealers, especially those selling slaves from India - whose people Britain had vowed to end the exploitation of. Additionally, the agreement stipulated the confiscation of slave ships and the protection of freed slaves.

A similar treaty was also enforced on Turkey bin Said Sultan, the ruler of Muscat, in April of the same year, in exchange for a pledge of compensation of his losses from the British government. Similarly, treaties were signed with the rulers of Sharjah, Salman bin Sultan al Qasimi, and Abu Dhabi, Zayed bin Khalifah al Nahyan.

The anti-slave trade treaties were Britain’s way of combating foreign competition in the area - especially from the French. Every time French influence threatened to expand to the area, Britain would revive its anti-piracy and anti-slave trade efforts, often culminating in a renewed agreement with the sheikh or ruler. When competition subsides, British authorities would ignore the slave trade altogether or even direct it towards its territories in Africa.

Nonetheless, France did not stand idly by in the face of British anti-slave trade tactics. In the Brussels Conference of 1890, the French expressed apprehension around abolishing slave trade. The conference was specifically called on by the Ottoman Empire and Britain to discuss this issue. Meanwhile, slave shipments continued to reach the city of Sur till the last decade of the nineteenth century. From there, they would be distributed to different Gulf areas and places of the Arabian Peninsula, effectively turning Sur into a primary supply center because of the slave trade ban in other cities.

The Finishing Blow From The Portuguese

What is noteworthy in this narrative was that the final blow to this trade - under the protection of the French flags - came not from Britain, but from the Portuguese who were occupying Mozambique in 1902, when news reached them that a fleet of 12 ships had suspiciously anchored in the small Samuko Bay on the coast of Mozambique. It turned out the Gulf was a small colony of Omani sailors who worked with notable activeness to trade slaves away from British eyes, all made possible with the sheikh of Samuko Bay Vampoita Mono.

The Portuguese surprised the bay with artillery, causing many to die or flee from them, while the rest were arrested along with their simple ships and weapons and the sheikh of Samuko was brought to trial, according to John Gordon Lorimer in the book “The Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf” (translated into Arabic by the translation department in the Amiri Diwan of the State of Qatar).

According to Shatab, the Portuguese standpoint was not one out of purely humanitarian sentiment, since the Portuguese had been, until then, among the fiercest and most violent colonizers in Africa and the most supportive of the continuation of this trade. But their stance came in fear of shifting the French-British competition to their own colonies in Africa, and also in suppression of their Omani competitors in this trade.

The end of slave trade varied; In 1937, Bahrain issued a decree banning it; in 1952, Qatar announced the abolition of slavery; meanwhile Saudi Arabia issued the absolute abolition of slavery in 1962, Yemen followed the same year and in 1970, Oman followed

As for the Ottoman Empire and the Persian government, both entered two treaties with Britain in 1881, in which they pledged not to import any African slaves into their countries. The pledge also gave Britain the right to inspect their merchant ships in the Arabian Gulf, the Red Sea and the coast of Africa in search of slaves.

The two treaties entered into force in 1882, following a fierce Ottoman-British competition, alongside an intense and simultaneous Persian-British competition for the control of Bahrain and the eastern coast of the Persian Gulf that extended throughout the last quarter of the 19th century.

The Fate Of Freed Slaves

Up until 1889, it was customary to move freed slaves to Bombay if they were unwilling to remain in the Gulf. However, towards the end of that year, the Bombay government began to complain of the increasing number of enslaved people on its soil, considering them a growing disturbance, according to Lorimer.

Consequently, efforts were made to find a way out using a different course, including the Straits of Sarawak (in Malaysia), Fiji in the south Pacific, and the island of Borneo (divided between Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei), but the governments of these regions responded unwillingly and negatively to receiving any liberated Africans.

Things remained the same until 1897, when the government of India itself began to oppose the import of freed slaves to its soil, suggesting sending them to East Africa instead, which is actually what happened. According to Lorimer, they were sent to work on the plantations of the Sultan of Zanzibar.

It seems this trade had not completely stopped by the beginning of the 20th century. On November 5, 1926, the ‘Daily News’ newspaper reported that the British government signed a pact with 30 governments in Geneva in September of that year to cut off this trade for good. This came following reports of its practice among the pilgrims going to and returning from Mecca, as pilgrims would return to their countries with a number of slaves, as mentioned by Shatab.

Shatab says that Britain fought the slave trade through the ships it monitored in the Gulf. It transported them to various parts of the world throughout the 19th century, while not paying any attention to the liberation of the local slaves native to the region or their rehabilitation after they were laid off work on diving ships following the collapse of the pearling industry during the thirties of the 20th century. They suddenly found themselves without work or families to shelter them, while the presence of slaves remained rampant in the region until the sixties of the 20th century.

The time of the end of slave trade in the Gulf varied from one country to another. In 1937, the ruler of Bahrain Hamad bin Isa bin Ali Al Khalifa issued a decree punishing those who practiced slave trade. Nine years later, that is, in 1945, what came to be known as a "manumission certificate" was issued and granted to emancipators.

In April of 1952, Qatar announced the abolition of slavery. In turn, those enslaved became free, integrated into society, and were later granted Qatari citizenship in 1961.

In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Prince Faisal bin Abdulaziz, Crown Prince and Prime Minister of Saudi Arabia, issued his reform program on November 6th, 1962. Known as the "Ten Points of Reform", its 10th point stipulated the absolute abolition of slavery, the emancipation of all slaves, and compensation for their owners.

In Saudi Arabia, Prince Faisal bin Abdulaziz issued his reform program on November 6th, 1962. Known as the Ten Points of Reform, the 10th point stipulated the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of all slaves, and compensation for their owners.

The same year witnessed the end of slavery in Yemen, following the outbreak of the revolution there, with both the constitution and law criminalizing the practice. Meanwhile the slave trade was banned in the Sultanate of Oman in 1970.

رصيف22 منظمة غير ربحية. الأموال التي نجمعها من ناس رصيف، والتمويل المؤسسي، يذهبان مباشرةً إلى دعم عملنا الصحافي. نحن لا نحصل على تمويل من الشركات الكبرى، أو تمويل سياسي، ولا ننشر محتوى مدفوعاً.

لدعم صحافتنا المعنية بالشأن العام أولاً، ولتبقى صفحاتنا متاحةً لكل القرّاء، انقر هنا.