This article comes as an in-depth coverage of the October 18 lecture from the American Research Center in Egypt (ARCE) by American Egyptian researcher Iman Abdulfattah; Ph.D. Candidate preparing her dissertation in Islamic Art and Archaeology at the University of Bonn and teaching Islamic art and architecture at the NYU School of Professional Studies.

The ‘Lion of Cairo’, ‘the legendary merchant’ and ‘the greatest expert’; all these titles belong to one man. This prolific dealer of antiquities gained prominence as the go-to man among the intelligentsia of Egypt in the late 19th - early 20th century, a time when Middle Eastern archaeological discoveries ensnared the attention of museum directors and art connoisseurs arounf the globe.

While private and public collections gathered by individuals and institutions were largely dictated by the expertise of a well-connected network of antique dealers, Maurice Nahman (1868-1948) would soon become one of the most knowledgeable and influential in the field. Nahman began operating out of Downtown Cairo, dealing in Egyptian antiquities sales in 1890, and it wasn't long before his fingerprints spread to top museum operators across Europe and the United States.

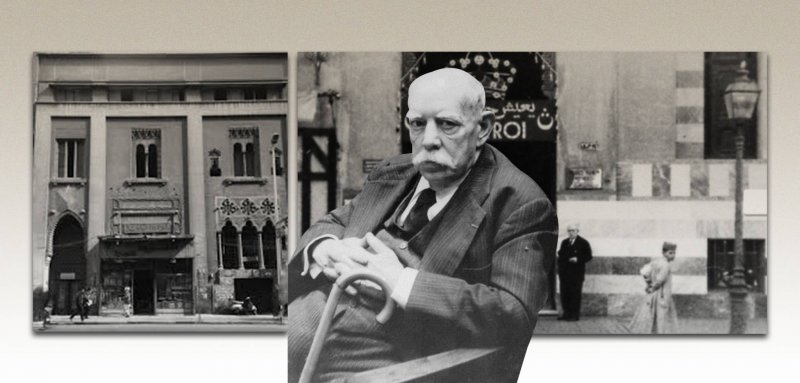

Meet the ‘Lion of Cairo’, Maurice Nahman, the Jewish dealer who gained prominence in antique trading in Egypt, and whose fame spread far and wide throughout 20th century Europe

Not only the leading authority on ancient Egyptian artifacts, Nahman was also well known for acquiring rare collectibles of modern Egyptian history. His personal collection would supply the acquisition of Islamic and Coptic pieces of the highest quality by international museums. On many occasions, Nahman’s vision and expertise were behind the establishment of novel museum departments dedicated to these fields and helped shape public and private perceptions in such an emergent domain.

“Meet the ‘Lion of Cairo’, Maurice Nahman, the Jewish dealer who gained prominence in antique trading in Egypt, and whose fame spread far and wide throughout 20th century Europe

Thus, the American Research Center in Egypt dedicated this year’s October lecture to one of the most formidable and influential figures in the field with the help of American Egyptian researcher Iman Abdulfattah, a Ph.D. Candidate preparing her dissertation in Islamic Art and Archaeology at the University of Bonn and teaching Islamic art and architecture at the NYU School of Professional Studies.

From teller in Egypt’s oldest bank, Syrian Jew Maurice Nahman began his career collecting and selling antiquities, and was soon sought out by the most prominent archaeologists and richest collectors from around the world

Due to her research and interest in the network of antiquarians active in Egypt during the first half of the 20th century, Abdulfattah gives us a closer look at the life and career of Maurice Nahman under the title, "Maurice Nahman: Collector, Dealer, and Authority In The Antique World". We showcase the lecture’s highlights in this article, as we focus on his relations with art historians, curators, and collectors inside and outside of Egypt

Who Is Maurice Nahman?

It is the 20th century, the time of European travel and exploration. As the collection of antiques aligned with Western imperialistic fantasies, museum curators and art collectors across the globe had their eyes set on the jewels of Egyptian archaeology. The fascination with artifacts from ancient Egypt made its way across the pond to America, where affluent private collectors, museum directors, and researchers alike joined the hunt for Egypt’s best.

The influence of orientalist paintings and the representation of Egypt at world fairs held between 1851 and 1903 saw the establishment of the Antiquities Service in 1858 and the Committee for the Conservation of the Monuments of Arab Art in 1881; both of which supplied artifacts to museums in Cairo. In the midst of all this, a well-connected network of collectors and dealers in possession of vast assemblies of artifacts left their mark in the field. One such notable figure is Maurice Nahman.

Abdulfattah notes the deference Nahman held among papyrus paper scholars. Not only was he reputed to own a significant collection of the ancient papyrus paper scrolls, but he was also widely known for his integrity and impartial evaluation of the pieces; often employing an academic method to detect frauds and forgery. While following Nahman’s career seems straightforward enough at first glance, a general scarcity of information engulfs our understanding of his life and complicates the task for researchers. Unlike his colleagues and contemporaries from the Tano family - of whom we mention Phocion J. Tano, the Cypriot dealer of papyri belonging to the Nag Hammadi library - little has been documented of Nahman’s life.

There is no written record or study on Nahman. Nor are there any documents from any archives that can shed light on his life. The abundance of information fellow antique dealer Kelekian enjoys is at a stark contrast with our knowledge on Nahman. The Metropolitan Museum of Art holds an archive of Kelekian’s work: from correspondences and shipment inventories to catalogues and photographs, a lot is known of the Armenian trader who dealt in ancient Egyptian antiquities in Cairo. Unlike many of his peers and contemporaries, Nahman remains an elusive figure shrouded in obscurity. According to Abdulfattah, what little we know of the dealer’s early life comes from the book Who Was Who in Egyptology, which confirms that Nahman was born in Cairo in 1868, to Sarena Rosano and Robert Bek, a banker father, and that he showed interest in ancient ruins from an early age.

Nahman’s impeccable French and near-native fluency in English demonstrate his superior education. He was hired by the Crédit Foncier Égyptien Bank in 1884, and became a cashier in 1898, before rising to the ranks of chief-teller in 1908 – a position he held till 1924, when he retired and dedicated his life to his exhibition.

Simultaneously, his passion for ancient ruins led him to establish himself as an antiques dealer in 1890. He later purchased a property in an affluent area in Cairo, Madabegh Street (now known as Shareef Street), to set up his gallery.

Even though Nahman was born in Cairo, Abdulfattah references his Greek roots, unlike a 2015 publication that cites a letter between Francis Kelsey, professor and archaeologist at the University of Michigan, and antique collector David Askren.

Not only was Nahman a well-connected dealer, but he also carried a special license from the Egypt Museum to sell antiquities, something that gives insight into the breadth and diversity of his professional relationships

However, the family’s greatest ancestor Matatias Nahman was a from northern Greece. In fact, many Greek merchants who rose to prominence in the Middle East acquired their wealth in various commercial industries like cigarette, cotton, chocolate, and soda production. We also know from their family tree that members of the Nahman family married into some of the wealthiest Jewish families in Egypt.

“From teller in Egypt’s oldest bank, Maurice Nahman began his career in collecting and selling antiquities to become sought out by the most prominent archaeologists and richest collectors from around the world.”

Established in Alexandria in 1880, the bank Nahman began his career in was the first bank in the country. Egypt was still in the middle of an economic and political crisis, so from 1882 to 1883 business was slowed down significantly and the bank closed temporarily. The same year a 16-year-old Maurice began working at the bank marked the beginning of its recovery from its financial crisis, after which Nahman’s successful career as head teller remained until his retirement in 1925.

No doubt Nahman’s 41-year tenure at the bank brought him into contact with a number of vintage collectors and art connoisseurs who had access to antiquities. It is told that European collectors and antique experts would seek out his gallery in particular in order to acquire original pieces, namely Belgian Egyptologist Jean Capart, who was one of Nahman’s most important clients and dubbed him the “world’s greatest Egyptian antique dealer .”

A page from the guest book of Maurice Nahman’s Gallery

In addition to having such notable social ties, Nahman’s success comes greatly owing to his distinguished talent, impeccable taste, and broad experience, as well as deep insight into Egyptian archaeology. In the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for instance, items that have gone through his gallery are the most prominent in the collection. Several such pieces are located in the Egyptian Art Section, like the famous Hippopotamus figurine (popularly called "William").

(Hippopotamus (“William”), Egypt, (ca. 1961-1878 BCE), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Public Domain image).

Not only was Nahman a well-connected dealer, but he also carried a specific permit from the Egyptian museum to sell antiquities, something that gives insight into the breadth and diversity of his professional relationships and how museums view them. A true reference to the distinguished individuals, academics and political figures, the “Nahman Guest Book” is kept in the Wilbour Library of Egyptology’s Special Collections at the Brooklyn Museum, after it was purchased from one of Nahman’s daughters, Alexandra Nahman Moncero, in 1976.

“Not only was Nahman a well-connected dealer, but he also carried a specialized permit from the Egyptian museum to sell antiquities, something that gives insight into the breadth and diversity of his professional relationships and how museums view them.”

Even though the visitor’s book doesn’t date before 1918, years after the gallery’s prime, it contains quite an impressive list of names, encompassing a wide range of archaeologists and scholars specialized in Egyptian, Byzantine, Middle Ages, and Islamic history.

Among the many signatories was renowned Islamic art historian and Louvre curator, Gaston Migeon; the most significant collector of precious manuscripts in the 20th century, Sir Alfred Chester Beatty; scholar and professor of Islamic art and archaeology, Leo Mayer; and Howard Carter, the archaeologist who discovered the tomb of King Tutankhamen.

Maurice Nahman’s possessions can be found today at the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, while the prized ‘Nahman Guest Book’ remains at the Wilbour Library of Egyptology’s Special Collections at the Brooklyn Museum

The exhibit also saw the recurrent visitations of countless collectors and dealers, the likes of Russian Michael Rostovtzeff, one of the greats of twentieth-century historical research; Armenian-American archeologist Hagop Kevorkian, as well as renowned American Egyptologist Bernard Von Bothmer. In addition, public names and political figures like senator and billionaire Maurice de Rothschild and John Rockefeller, one of the largest oil manufacturers of his time.

Nahman was able to foster interest into ancient Egypt not only through his professional dealings but also through pop culture, such as movies on this genre. He was such a critical player in the antiquities scene that he was the inspiration behind the character ‘Ayoub the dealer’ in the 1969 feature film ‘The Night of Counting the Years’ or Al-Mummia’ for Director Shadi Abdel Salam, a major figure in Egyptian cinema. ‘Ayoub the dealer’ is played by Egyptian actor Shafic Noureddin.

Maurice... Antiques Collector & Dealer

Through reading Nahman’s correspondence and letters, Abdulfattah confirms that he was a confident, knowledgeable, and steadfast negotiator who often precisely described the qualities of the items proposed for sale. Nahman’s antiquity business was launched in 1980 from two locations in the downtown Qasr El Nil Street of Cairo’s Ismailiya district, where many European consulates, government buildings, hotels, theaters, and shops convened.

It came to be known as one of a few places to purchase genuine antiquities in the 1910 Cairo guide compiled by French Egyptologist and Louvre curator George Benedict along with Max Hartz. Both his galleries stayed operational until 1919, when Maurice permanently moved to a mansion he purchased.

In 1914, the year that Nahman purchased the mansion, two main occurrences took place. First, it was the year his bank became the second most profitable business in Egypt following the Suez Canal, benefiting Nahman greatly. Secondly, the savoy hotel across the street from his gallery had been taken over by the British army who used it as its headquarters in the Middle East. Thus, the motivation behind relocating his business from Qasr El Nil Street to the Madabegh Street might have been due to an attempt to look for new clients.

Maurice Nahman Mansion in Cairo. Emile ou François (?) Burdet, Casa Nahman (ex-cercle artistique), last quarter of the 19th century-1st quarter of the 20th century, Inv. No. A 2006-0029-340 (© Musées d’art et d’histoire, Ville de Genève).

Inscribed on the façade of the mansion Nahman bought is an Arabic inscription that reads, “This residence was founded by Baron Dolor Degleon for his own use.” The Baron was also a collector of Islamic art. He donated many items while the rest of his collection was bequeathed to the louvre museum posthumously. Although it was registered in the Bureau of Egyptian Antiquities as a significant monument in 1995, the mansion currently remains abandoned.

The mansion, designed by a French architect, served as a distinguished landmark in Cairo’s social and cultural life. In 1891, the mansion housed the ‘cercle artistique’, the first art society to be established in Egypt where international and local figures showcased their work.

The Madabegh mansion housed a great variety of objects from different periods. Nahman was described by James Henry Breasted (1865-1935) in a 1919 letter to sponsor Charles Hutchinson (1854-1924) as a “rich man living in an massive house with a huge drawing room, as big as a church, where he exhibits his vast collection.” In 1920, the mansion hosted a public auction in order to draw attention to his new gallery and attract new clients.

Abdulfattah suggests that the date indicates that there might have been a need to compensate from the loss of business during World War I, under a crippled postwar economy and lack of political instability following the 1919 revolution against British occupation.

“Maurice Nahman’s mansion served as a distinguished landmark in Cairo’s social and cultural life, housing the ‘cercle artistique’, the first art society to be established in Egypt where international and local figures showcased their work.”

Affairs Inside & Outside Egypt

Items sold in the Nahman gallery represent prominent antique collections from all regions across the world. Abdulfattah asserts that the gallery’s guest book is also counted as a rare antique holding priceless information.

Maurice used to sell antiquities from the late Islamic age, and curators would purchase them before their museums held sections to house such items, thus they were stored in the Egypt or lower Asian sections, until a Medieval section was conceived.

The 1920s and early 1930s were the most active for Maurice Nahman, whose signature could be found on hundreds of antique purchases and transactions. For example, Nahman donated a wide range of antiquities to the Museum of Islamic Art at the time. He went on to donate dozens of other items in the 1930s, including linen cloths embroidered with silk, a wooden altar from the Fatimid era, as well as a vase from the Mamluk period.

In order to conduct business with museums in Europe, Nahman spent his summers at the Grand Hotel in Paris, eventually offering a collection of 10th century textile fragments to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1934. Various correspondences prove that great interest was shown in five silk fragments. He described them as “fine in quality, unusual in character and design, and quite good in color.” He went on declare that nothing resembling these textiles has been showcased in Cairo before, validating their worthiness and his ability to acquire rare items.

Nahman held his second public auction via Christie, Manson and Woods in 1937 London. Nahman was concerned over the outbreak of a second world war, a fear that prompted him to consign 120 items. For some reason, his name was not advertised as the owner of the collection, hence buyers were unaware that they were purchasing Nahman stock. However, the auction did not yield the desired outcome, partly due to the large number of forgeries in the market at the time. In consequence, Nahman expressed in a letter that he was prepared to end his days as a dealer and considered selling his entire stock to a small museum for half its value, according to Abdufattah, but nevertheless, he persisted.

A year later in 1944, around 10 tapestry woven textiles and 30 sculpted wood and stone pieces from Nahman’s collections were loaned to a contemporary exhibition on Coptic art in Cairo. The third and final auction during Nahman’s lifetime was held in 1947 at his gallery in Cairo.

End of An Era

“Maurice Nahman’s possessions can be found today at the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, while the prized ‘Nahman Guest Book’ remains at the Wilbour Library of Egyptology’s Special Collections at the Brooklyn Museum.”

Maurice Nahman’s possessions can be found today at the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo as well as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, while the prized ‘Nahman Guest Book’ remains at the Wilbour Library of Egyptology’s Special Collections at the Brooklyn Museum.

Abdelfattah theorizes that the last auction could have been a last-ditch attempt on the part of Nahman to recover from the impact of the second world war. Another possibility suggests that during that same year, al-Majless al-Hizby or ‘probate court’ permitted the sale of Nahman’s collection, indicating that his estate was being liquidated. Nahman might have been gravely ill at the time, since he passed away not long after on March 18, 1948, at the age of 80. The location of his grave is presently unknown, though it is possible he was buried in the historic Basateen Jewish Cemetery given that several generations of his family members rest there.

Upon Maurice Nahman’s demise, his gallery remained open to the public for several years before his estate and remaining collection was divided among his children, resulting in two posthumous auction sales in 1953.

The death of Maurice Nahman seemingly marked the end of an era, but did not mark the end of his influence, as many of his collections made their way into esteemed exhibit halls and notable museums, public and private alike. Unfortunately, Nahman’s contributions to the growing appreciation of Coptic & Islamic art is an aspect of his impressive career that is overlooked. Consequently, he has faded to obscurity outside of Egyptological circles, even though his memory remains preserved in world museum archives.

Nahman’s collections, ranging between antique jewelry, Coptic textiles, Roman statues, Arabic pottery as well as glass ceramics, can be found today in the Islamic art section. Every collection tied to his name at the Metropolitan museum has been said to amplify the richness of the exhibit.

In addition to describing him as a collector and dealer, Abdulfattah also refers to Nahman as an authority in the antique world, owing to his vast experience and interest in a wide range of topics. She states that Nahman gives off the impression of a well-read expert in world history.

Finally, it is also important to place Nahman’s career in the context of a contemporary political climate, since he operated during a formative period that began with the British occupation of Egypt in 1882 and culminated during the period between World War I ,the revolution of 1919, and the outbreak of World War II.

"Maurice Nahmann in his gallery.", 1945. B/W photograph (original print). Brooklyn Museum, Wilbour Library of Egyptology, Special Collections

رصيف22 منظمة غير ربحية. الأموال التي نجمعها من ناس رصيف، والتمويل المؤسسي، يذهبان مباشرةً إلى دعم عملنا الصحافي. نحن لا نحصل على تمويل من الشركات الكبرى، أو تمويل سياسي، ولا ننشر محتوى مدفوعاً.

لدعم صحافتنا المعنية بالشأن العام أولاً، ولتبقى صفحاتنا متاحةً لكل القرّاء، انقر هنا.