Much to the Nubians regret, their displacement came long before the days of the internet, for the world today has no idea of their forced displacement and their fate, one of the oldest cultures in the world is now facing extinction. When talking about bad luck and the threat of extinction together, the policies of the Egyptian state which combines both an Arabist disposition that looks down on other cultures combined with a frowning on African origins and roots that appear particularly evident - a tendency also adopted by the former Sudanese regime, which first led to the independence of South Sudan and is one of the main factors leading to the present revolution in Sudan.

In a clear example demonstrating that the concepts propagated today of “citizenship” and “harmonious societies” are not understood in the same terms by everyone, the initiative taken by the writer and thinker Haggag Oddoul - the Nubian representative in the ‘Committee of 50’ tasked with drafting the new Egyptian constitution in 2013 - to propose a constitutional article recognizing other Egyptian languages (Amazigh, Coptic and Nubian) as local languages, was met with a heavy attack by various Egyptian intellectuals - the most prominent of which were the poet Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi and the actor Hamdy Ahmed, who even attacked the notion of the Nubians returning to their original areas.

Evidence of Ill Intention

The targeting of the Nubians was not only restricted to the debates of the Committee of 50 on the ‘Nubian problem’ or to articles by some intellectuals and politicians, but also reached the extent of promulgating laws and issuing official decrees.

Thus, when the Egyptian monarchy decided in 1933 to legalize the flooding of a number of Nubian villages, the then-Egyptian government of Ismail Sidqi innovated a “Special Law” to legitimise the seizure of Nubian-owned lands - in the process ignoring Law Number 27 of the year 1906, which regulated the process of stripping private ownership for public benefit.

Here, the speech given by the Minister of Works Mohammed Shafiq Pasha in the Egyptian Senate serves as an indictment of the Egyptian government and state, which at the time wanted to rush implementation of its plans without respect for the law.

At the time, the minister declared: “Egypt has spent millions on creating the Aswan reservoir and elevating it, and all of you esteemed present are anxious to see the increase in water and our hopes now rest on the method of its storage; if we wait five years until we complete the stripping of ownership in the ordinary fashion we would have then deprived Egypt of water, an unjustified material deprivation; abiding by the current law with regards to the stripping of ownership would deprive Egypt of water throughout this period; if the proposed law (27) allows us to place our hands on the agricultural lands, it is not possible for the judiciary or the experts or the stakeholders to know the features of the land after it had been inundated with water this coming November.”

In comparison, during the Republic days, the country would witness the displacement of the inhabitants of the Suez Canal cities because of the war with Israel, as well as the displacement of what remained of the Nubia’s natives in order to make way for the construction of the Aswan Dam. Following the end of the war with Israel, the state would reopen the door for the return of those displaced from the Suez Canal cities, launching what was known then as the “Battle of Defiance and Reconstruction.”

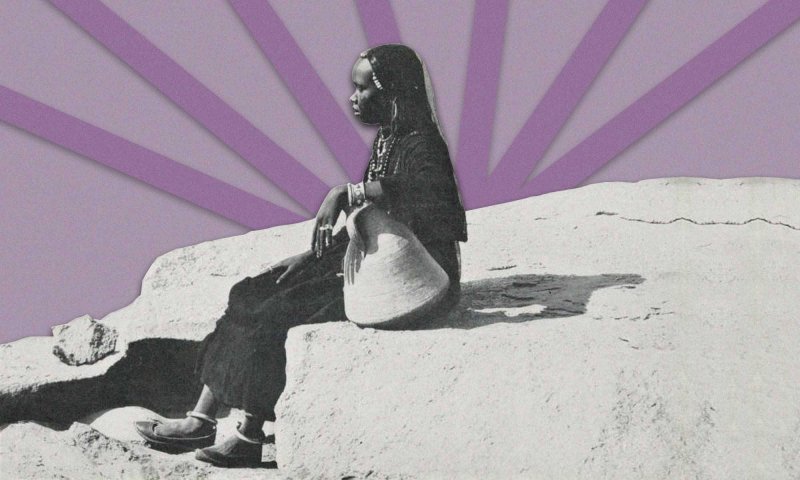

The Nubians: the untold story of an old African culture marginalized by Arab nationalism combined with racism against Africans in an ever more Arab Egypt.

To create the world’s largest artificial lake and irrigate land in Egypt, Nubian villages were flooded repeatedly for the greater good. What was the impact on an old and proud African culture?

Accordingly, the state would establish tourism projects in Ismailia (one of the Suez Canal’s main cities), declared Port Said a free-trading zone and rebuilt the petroleum facilities in Suez, measures which offered living and work opportunities for the returnees, and the three cities would also become economic centers.

By contrast, the state would not take similar measures in the south following the stabilization of the water-level at Lake Nasser (the reservoir behind the Aswan High Dam) - even when the necessary funds for returnees became available in the state coffers - not to mention sources of funding outside the state’s treasury. Amongst these sources were the Food Relief project funded by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization as well as the Rescue Fund to Save the Monuments of Nubia, one of the largest private funds and which relies in large part of its funding on collecting $2 USD from every entry visa into the country since the year 1964.

The state continued to ignore the opportunity to reopen the door of return to Nubia’s residents, despite proposals and suggestions put forward by states that contributed to the Rescue of Nubia’s Monuments fund: namely to allocate a portion of the returns from Nubian monuments to reconstruction and guaranteeing the future funding of a process of sustainable development in the region.

The Land of Fish and Gold

What happened in Nubia was not only the result of an Arabist impulse however, but was also driven by major economic interests rooted in the area. Here, we speak of a wide and extremely-fertile plot of agricultural land, as well as of Lake Nasser and its substantial fishing resources.

The total size of the agricultural land in the region reaches approximately 68,000 square kilometers, as well as 150,000 feddans (roughly equivalent to acres) of coastline agriculture. The lake meanwhile extends to an area of 5,250 square kilometers and a length of 500 kilometers, making it the largest artificial lake in the world. It was created in 1970 from the water that collected in front of the Aswan High Dam, and was labelled ‘Lake Nasser’ after the former Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser.

The lake is considered a major source of fish production, with an output of 20,000 tons this year. Indeed, ‘Lake Nasser’ is considered the only place in Egypt hosting African crocodiles.

In addition to the agricultural land and the abundance of fish, Nubia also hosts a mineral fortune that cannot be underestimated, namely gold. Indeed, the word “Nub” in ancient Egyptian means gold, and the country of Nubia is described as the “Land of Gold.”

It should also be noted that the most famous gold mine in Egypt, the Sukari Mine, lies in the Nubian desert - while the area richest in gold is the region of Mount al-Alaqi, named after the Nubian village of al-Alaqi.

The Whole Story

After Muhammad Ali Pasha’s unification of Egypt in the nineteenth century, and following his defeat of the Mamluks in the north of the country and the disciplining of the governor of the Sa’id (Upper Egypt) and the commander of the Houara tribe, Sheikh al-Arab Hamam in the south, the Pasha also militarily incorporated the emirates and princedoms of the southern Nile valley: such as Nubia, the Fur, Sennar and Funk. This was before the gradual decline of the state and the eventual occupation of both Egypt and Sudan by Britain in 1882.

In 1899, the borders between Egypt and its southern colonies were demarcated under the “Condominium agreement” signed between the British and Egyptian governments.

Thus the southern borders of Egypt were defined and a new country formed called “Sudan.” As for the Nubians, they found themselves divided amongst Egyptian villages such as al-Fajika, al-Matokiya and Arab al-Alaiqat, and Sudanese villages including ad-Danaqlah, al-Mahas, al-Sakut and al-Halfawiya.

The Age of Migration

Subsequently, Britain decided to utilise the flood-water and store quantities of it, and so the “Aswan cistern [reservoir]” was opened in 1902, being elevated for the first time in 1912 and then again in 1933 - with Nubian villages being drowned by flooding on both occasions.

Indeed, during the various stages of elevating the reservoir, 28 Nubian villages were drowned, and with them land and palm trees, markets and wells, houses and graveyards, farms and livestock, memories and monuments… all these were swallowed by the Nile, and left the inhabitants with no history and no source of living.

Between Destitution and Stereotyping

During the flooding of Nubian villages, large-scale waves of migration towards the north took place in search of a better life, only women, children and the elderly remained to inhabit areas that were barely suitable to sustain a life.

During this period, black skinned people with a broken Arabic accent started to appear in Cairo and Alexandria, most of whom clearly appeared foreign to the city and alien to the local lifestyle. Many Nubians accordingly found themselves at the bottom of the urban social ladder, failing to find any institutions to incorporate them - indeed, instead finding a cinematic machinery that facilitated the drawing of stereotypes of the Nubian who can only have a single name - “Othman” - the possessor of a comedic accent who worked as a doorman or waiter.

Independence Didn’t Affect Nubians

After the downfall of the monarchy, the evacuation of the British forces, and the construction of a ‘national state’ across the two halves of the Nile Valley, the Egyptian state decided to affect a number of major changes - such as industrialization instead of relying mainly on agriculture, by extension changing the pattern of the latter from being seasonal-based to year-long farming, as well as striving to deliver electricity and drinking water to the largest number of citizens.

In order to accrue all of these benefits in the north, the state had to construct the Aswan High Dam, which meant more drowning of Nubian villages in the south; the dam would store water for up to a level of 183 metres, which would result in the drowning of the entire lands of Egyptian Nubia. None of the area’s residents remained - theoretically - other than those who sought refuge in the mountains, in time leading to those areas becoming known as “The villages of the waterfall.”

This was from the Egyptian side; meanwhile south of the border, the area of Halfa in Sudanese Nubia was drowned, as well as 20% of the lake’s area inside Sudan - with this portion officially known as “Nubian lake.”

Furthermore, because the displacement of the population was implemented in a rush and without sufficient studies on the effect of such a policy, many catastrophes would follow: thus, ‘alternative’ villages would be built in the desert of Kom Ombo with cement and without domes, effectively representing collective graveyards.

Furthermore, during the first year of displacement and because of the sudden and severe change in the climate, many of the region’s elderly died, as well as a whole generation of newborns.

The Myth of Compensation

The compensation that would eventually arrive for the Nubian residents would be extremely meager, with the price of a palm tree being estimated between a tenth to a half of an Egyptian Pound - according to a book published by the Management for Information and Public Relations tasked with keeping records of the displacement process.

These numbers were much less than the value of the lost items, as is made evident by the disparity between the estimations of the property owned by Egyptians and the equivalent owned by Sudanese. Furthermore, the compensation sums were not paid out in full – with current discussion today of disbursing the balance.

Comparing the compensation sums between the Egyptian and Sudanese equivalents, the compensation sum in Egypt for a palm tree ranged between 10 to 50 Piastres (a tenth or a half of a single Egyptian pound), while the equivalent sum in Sudan ranged between 15 to 43 Egyptian Pounds.

Census Problems

During the second elevation of the water reservoir, an attempt was made to record the Nubian population, and a commission was sent to the villages - however, these would not take into account those displaced in the north during the first lake elevation, and similarly ignored those harmed by the first and second elevations.

During the preparation for the construction of the High Dam at Aswan, and because the census of those “migrants” was taken in a hurry, the results thus lost much of their accuracy. Today meanwhile, the census process - in its current form - can be considered a frivolous exercise, because it is a right belonging to all Nubians - with the Nubians currently present being the grandchildren and descendants of those who were forcibly displaced during the last century

All of this harm and the sacrifices by the Nubian community did not warrant a single line in Egypt’s educational curricula, while the Nubian language that helped in the military victory of the Egyptian Armed Forces continues to go unrecognized; meanwhile, Nubian culture rarely makes an appearance in the state’s official media.

Nor is there any designated day that can remind society of the role of the Nubians, despite the annual celebration of the construction of the Aswan Dam - where every year the story is told of the struggle for the dam’s construction, while no mention is made of the sacrifices it entailed.

The Manoeuvres Stage

Lately, many voices have arisen demanding the state resettle the Nubians in their original areas - a demand that was recognised in Article 236 of the constitution which stipulated the right of the Nubians to return to their original areas.

However, despite this constitution, the Egyptian state has adopted a policy of obfuscation, mixing up issues and wasting time and effort - notably in the form of irrational and unsuitable details of the plan, such as:

- Asking for ownership titles for those who wish to return - an irrational demand as the forced displacements by the reservoir’s construction took place before the foundation of the Real Estate Registration Office; it is furthermore self-evident that every Nubian now is a descendent of a displaced Nubian. Furthermore, the Nubians are an indigenous people who the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples applies to.

- The state’s insistence on rhetoric repeated by the governor of Aswan declaring “the end of the question of compensation,” despite the fact that what most Nubians need is to return and rebuild their old villages - with such a return constituting a fundamental right for Nubians in the same way that their displacement was forced on the whole population.

Meanwhile, the talk here of the requirement to “prove harm” or build the same number of houses that were drowned is - if not malicious - then actively absurd. Those who were originally displaced have since become grandfathers and grandmothers to extended families: how are these now expected to share the same home with their children and grandchildren?

- The promulgation of the Presidential Decree No.444 for the year 2014, regarding the regulation and facilitation of life in the border regions. The Decree in fact transforms huge swathes of Nubian territory into military-owned land, which it is prohibited to visit or requires at the very least a military clearance. Furthermore, it is apparent when reading the articles of the decree that the decision appears to have been specifically prepared to preclude the constitutionally-demanded right of Nubian return.

رصيف22 منظمة غير ربحية. الأموال التي نجمعها من ناس رصيف، والتمويل المؤسسي، يذهبان مباشرةً إلى دعم عملنا الصحافي. نحن لا نحصل على تمويل من الشركات الكبرى، أو تمويل سياسي، ولا ننشر محتوى مدفوعاً.

لدعم صحافتنا المعنية بالشأن العام أولاً، ولتبقى صفحاتنا متاحةً لكل القرّاء، انقر هنا.