Ahmed Umar grew up between Sudan and Mecca before moving to Norway as an asylum seeker at 20.

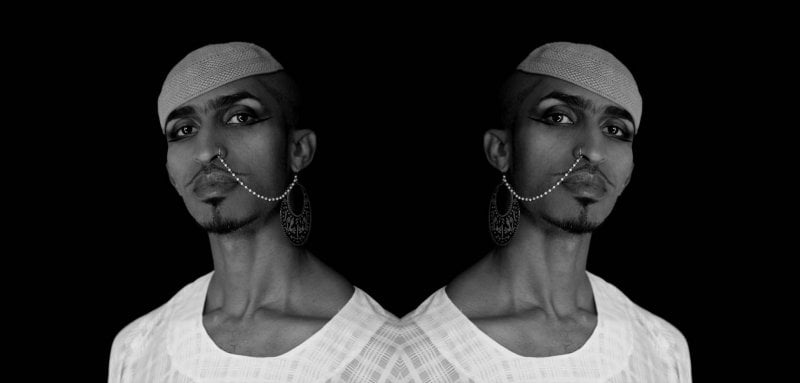

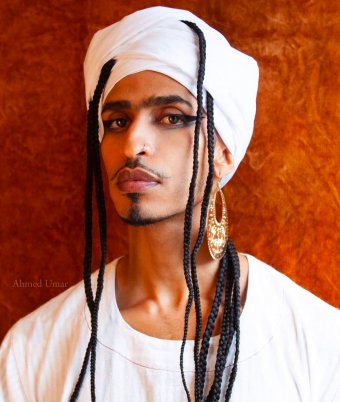

Now 37, Umar is considered one of Sudan’s most prominent multidisciplinary artists. His artistic repertoire spans sculpture, painting, photography, performance art, and dance, as well as fashion and jewelry design.

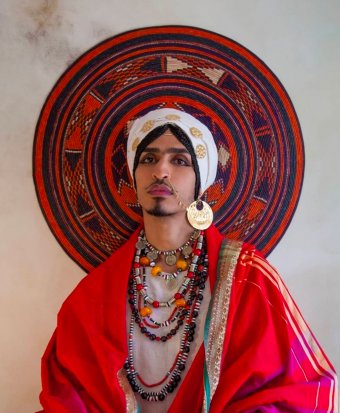

Despite all the challenges he’s faced, Umar’s work is deeply rooted in Sudanese culture, weaving artistic narratives inspired by traditional arts and Islamic motifs into a unique fusion of heritage and modernity.

Art for refuge

Umar was raised in a conservative, artistically-inclined family. His father was gifted in Arabic calligraphy, while his mother excelled at henna design – an environment that nurtured his creative talent from a young age.

“I started drawing as soon as I learned how to hold a pencil,” Umar tells Raseef22. “I believe I inherited the art gene from my parents – they’re both artists by nature. If they had the right circumstances, my father could have been one of the most prominent calligraphers today, and my mother would have been famous for her henna art. She also has exquisite taste in fashion and styling.”

“I couldn’t bear the burden of making everyone happy at the expense of my own joy, dreams — even my identity.”

Since childhood, Umar found refuge in art and preferred it over engaging with his peers in Sudanese society. Even today, his social interactions remain limited.

“Art has always been my compass. Drawing was the only thing no one criticized. On the contrary, I was constantly praised and encouraged for my talent,” says Umar. “It was my space for freedom, accepted by all and free from judgment.”

“In a country as unfortunate as Sudan, art doesn’t put bread on the table. I was pressured into studying engineering and eventually gave in. But I secretly dropped out after a few months of torment and enrolled in the Faculty of Fine Arts, where I excelled from the start.”

Reflecting on the challenges he faced, Umar notes he was raised in a conservative household within a “rigid, closed-off society.” He cites activist Sarah Hegazi’s death as a major source of motivation.

“The older I got, the less I could endure living a false life in which I had no say. I couldn’t bear the burden of making everyone happy at the expense of my own joy, dreams – even my very identity,” Umar tells Raseef22. “That reality plunged me into a deep depression and a total loss of will to live. To pull myself out of that darkness, I made the decision to leave Sudan for a more just environment in Norway, where I’ve pursued the challenges of life and art with determination.”

Umar’s artistic practice is rooted in storytelling – narratives that mostly emerge from his personal life, emotional responses to the events he’s lived through, and the things he strives to change.

I see my art as a way of shedding light on these experiences. It becomes a window through which others can understand what I’ve gone through, especially when it comes to my gender nonconformity and its consequences.

"While some people can express themselves through words, writing, or filmmaking, I express myself through body language and visual art. I pay close attention to the choice of materials and mediums that align with the message I want to convey – because every detail in the work represents an important part of the story."

"I feel a deep connection to everything Sudanese. I love this homeland in all its details – its nature, its land, its cultural heritage, even our dialects and popular expressions."

Umar gives a nod to Raqis al-Aroos (‘The Bride’s Dance’), one of the oldest traditional wedding rituals in Sudan, as an ode to Sudan’s cultural heritage.

“The bride dances proudly in front of the audience: her family, her husband, her future in-laws, and—in the past—the entire village. She wears a leather skirt with fringes, her chest bare, adorned with numerous gold and beaded necklaces.”

A woman’s dancing body, Umar points out, was not, up until the mid-20th century, a stage for men’s ‘honor’ or their supposed heroism. “But over time, public perception of dancing became poisoned, pushing it into near-obscurity – brides became cloaked in embroidered and glittery dresses, and the dance was restricted to women only.”

At 10-years-old, Umar was barred from attending one of his relative’s dances because he was male, but he didn’t give in. “I hid with my cousin on the balcony, and we watched the magic of the ritual unfold.” That moment left a deep imprint on him and shaped his artistic journey, inspiring him to perform the dance himself, wearing traditional dress he designed to resemble those worn by his grandmothers.

“I presented this performance piece at the 2024 Venice Biennale – and the resulting uproar hasn’t stopped since."

Sudanese heritage in Umar’s art

Despite his society’s rejection of his differences, Umar remains deeply committed to Sudanese heritage, which is visibly reflected in his artwork.

"I feel a deep connection to everything Sudanese. I love this homeland in all its details – its nature, its land, its cultural heritage, even our dialects and popular expressions.

“Like any other Sudanese, I have the right to draw inspiration from it and make it a living pulse in my artistic work."

"I drew the title of my project from the popular Sudanese saying ‘Shayel Wesh Al-Qabaha’ (‘bearing the face of ugliness’), used to describe someone who dares to break taboos and stand up against the norm – and the backlash and criticism they face for doing so."

After moving to Europe, his feelings toward his compatriots and the land grew clearer and stronger. He has since visited Sudan several times as a queer artist to carry out two projects that illustrated this deep connection and commitment to the country.

Umar describes his “Shayel Wesh Al-Qabaha” project as an important milestone in his career. The project reflects his personal experiences and what he faced after coming out as queer, and the wave of reactions questioning the influence – and the existence – of the LGBTQIA+ community in Sudan.

“Many claimed I was influenced by Western values, and that my actions did not represent Sudan. Some even described it as a vile act that nobody ‘from us’ would dare to commit."

Umar explains how the project highlights eight Sudanese individuals in Sudan who are active and influential members of their communities, yet are forced into hiding due to societal violence.

"I drew the title of my project from the popular Sudanese saying ‘Shayel Wesh Al-Qabaha’ (‘bearing the face of ugliness’), used to describe someone who dares to break taboos and stand up against the norm – and the backlash and criticism they face for doing so. It perfectly describes what I experienced when I was bullied after publicly coming out.

“I conducted interviews with these remarkable individuals, where we spoke about their dreams and their visions for Sudan. These interviews were exhibited alongside a photograph of each of us together. In the image, I lent them my well-known face to cover their own – to protect them from being identified or pursued by the authorities."

Umar shares that his upcoming project will pay tribute to Sudanese women revolutionaries who played a pivotal role in Sudan’s recent uprising. He hopes to celebrate the “women who have stood shoulder-to-shoulder with men in every political or social transformation the country has witnessed.

It’s customary for men to monopolize positions of power and exclude women from key leadership roles. I presented a series of portraits of Sudanese women who participated in the revolution with courage and determination. I made sure to portray them wearing traditional Sudanese dress – free from the influence of Wahhabism on our clothing."

Ahmed Umar affirms that the rejection he faces from his native society, of both himself and his art, has not and will not deter his passion to continue. He acknowledges that the lack of acceptance for gender diversity is common in our region’s societies, but never expected or hoped his own society would accept me as he is.

“I understood from a young age how difficult that would be, after seeing others rejected and subjected to violence simply for stepping outside what society deems acceptable, familiar, or the norm."

He recalls an anecdote from a seaside resort on the Red Sea. Somebody had spread a rumor Umar died in a car accident, describing it with such detail many had no choice but to believe it.

“I witnessed with my own eyes how thousands celebrated the news, cheering and proclaiming a great victory – only to be crushed with disappointment when I appeared alive. But I will never forget those whose humanity overcame societal judgment and prejudices, stepping forward to offer love and support. It is from them that I draw my strength."

Umar dreams of changing the negative perception of queer people in Sudan and lifting the fog that has divided them.

“I’m not shy about expressing my dreams openly. I aspire for my name to be among the most prominent names in the art world, and to be remembered in history for something I am proud to be: a distinguished artist with a noble message — Sudanese and queer.”

“The older I get, the more I realize I wasn’t born to live in Europe — even though Europe played a major role in helping me explore every part of myself.”

Speaking about his experience with public activism, Ahmed says that, over time, he became aware his life had come under the spotlight, and that every step he took subjected him to scrutiny — and accountability.

“I was compelled to voice my opinion on issues that concerned us as a community. While this has exposed me to harassment, it is a responsibility I did not seek out, but at the same time, it presents me with the opportunity to make a positive impact.”

What’s next?

Umar admits he has many dreams and a clear vision for the future.

“The older I get, the more I realize I wasn’t born to live in Europe — even though Europe played a major role in helping me explore every part of myself.”

Umar dreams of returning to Sudan and opening a contemporary art museum in the heart of Khartoum. He also dreams of seeing a flourishing, thriving artistic life to show the world who the Sudanese are through the art they create.

“A dignified life is a right for everyone, without exception. No one takes away another’s livelihood, work, or love,” Umar says.

“I hope the wars end, and that the Sudanese people find relief from displacement and suffering, so that we can build the homeland we love, through the way in which we love.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!