“I want people to understand that we’re Lebanese, but we’re also from the South. Both are indispensable sides to us. The land is ours, it’s part of our identity. We can’t let go of it.”

– Rasha Srour, Raseef22 English translator

– Rasha Srour, Raseef22 English translator

Two years after Israel withdrew its occupation forces from South Lebanon in 2000, Rasha’s parents spent whatever money they had saved on building a house in their village Aita al-Chaab.

Ali, Rasha’s father, outlined the blueprint for the house — built on land passed down by Rasha’s grandfather — transforming his plans into a family project. By 2005, they were furnishing the house into a home, and preparing to move in the following summer. Najibe, Rasha’s mother, spent her twenties traveling around the world, collecting antiques and souvenirs from different countries. In one corner of her newly built home there were the marble statues she had lugged over from Greece, in another she displayed rolled-up Egyptian papyrus papers. The collection was, as Rasha describes, her mother’s museum.

Israeli shelling during the July War in 2006 partially destroyed their home before the family had the chance to enjoy it. Still, Rasha’s parents rebuilt it, replacing the limestone façade with terracotta walls in time for their children to regularly visit after returning to Lebanon from abroad for university and work. It became the home where the family spent their weekends and their entire summers. On Friday evenings, after her night shift, Rasha’s brother and sister would wait out in the car for her so they could drive up before dawn, making use of every minute they had to leave the restlessness of Beirut for Aita’s tranquility.

Besides the images of her parents working the land, planting the fruits and vegetables that fed their family, and tending to the olive trees her grandfather had planted more than fifty years ago, Rasha’s home in South Lebanon brings to mind a wooden table — what she calls her father’s last ‘masterpiece.’ Made up of a variety of tiles collected throughout his life, and broken up and rearranged into a colorful mosaic before cementing them into place, the table was a testament to Ali’s patience and devotion to his home, a piece of him that the family held onto after he passed away in 2022. It is the one item Rasha wishes she could have saved before their family home was completely destroyed by Israel — after the ceasefire in November last year went into effect.

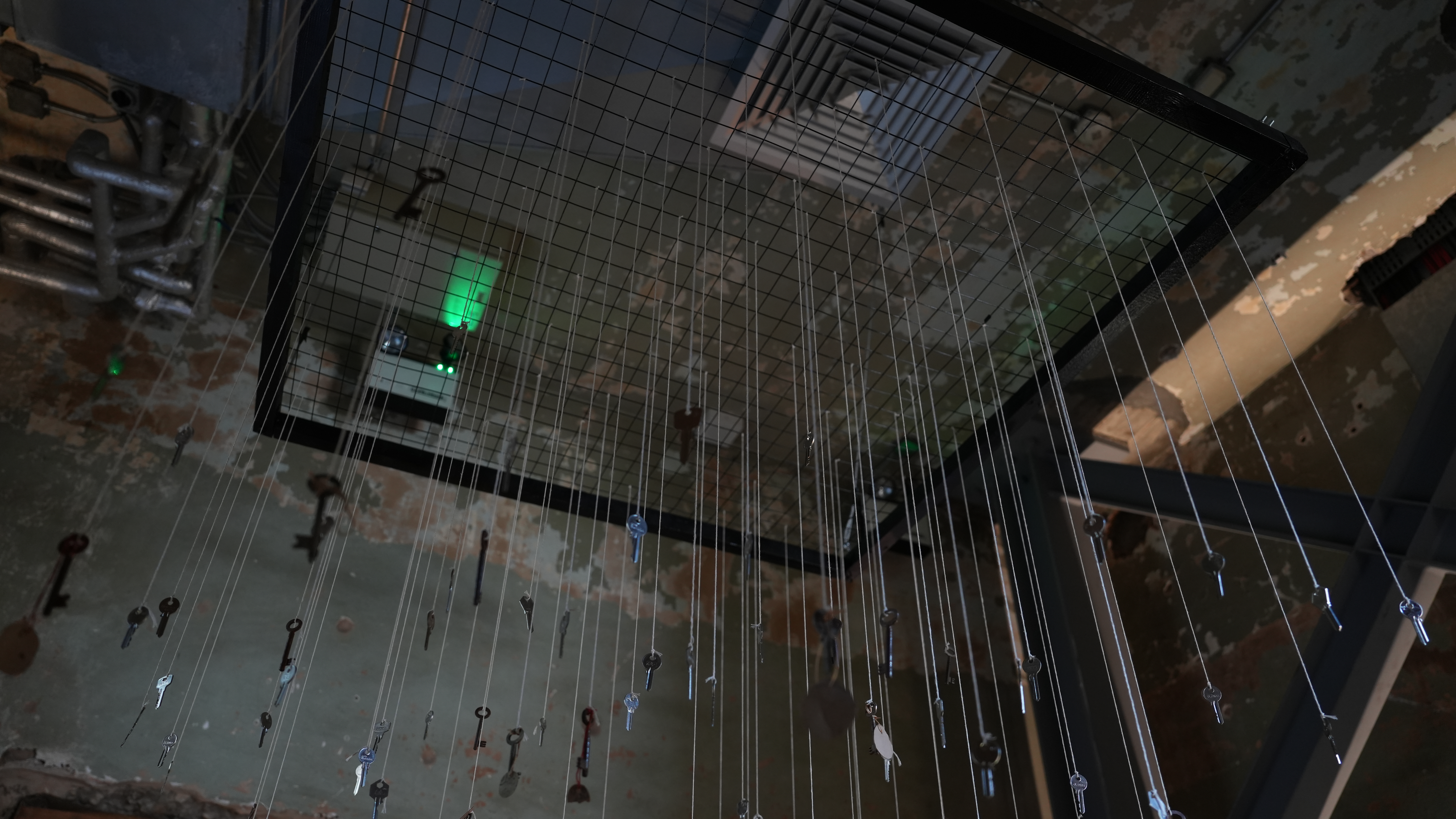

When we were pitching ideas about who we wanted to interview this summer, Rasha, Raseef22’s translator, mentioned that the archivist Adeeb Farhat had recently visited her home in Beirut to continue a conversation he had started with her mother at his exhibition in Beit Beirut. When Rasha’s sister took her and their mother to his installation “Keys Without Homes,” Farhat’s piqued interest in her mother’s life had moved her. Najibe was surprised by how much she saw herself, and her experiences, in the collected items he had displayed.

Despite it being his exhibition, swarmed by friends, visitors, press, and others eager to share their experience, Farhat listened carefully to Rasha’s mother as she recounted her life as a girl living in South Lebanon and her story as a woman who had lost the family home she had built with her husband over the years. He asked for her permission to record a testimony of what she carried in her bag every time she had to leave her home.

“He made her feel seen,” Rasha said.

To celebrate Farhat’s commitment to preserving Lebanese history, Raseef22 English sat with Farhat in his Beirut studio for his film and media production company “The Media Booth.”

We spoke about previous exhibitions, his motivations behind archival work, the challenges he faces as a pioneer in the local industry, and his future projects.I’m a filmmaker from Arabsalim, a village in South Lebanon.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you started your archival work.

My town was on the so‑called ‘security belt,’ a term coined by Israelis to distinguish between the occupied and unoccupied territories.

The images in the minds of those who lived through an occupation inevitably lead to working with audio‑visuals. Anybody who lived in the South — at least since the 1990s — experienced the 1993 War, Nabatieh Faouqa’s massacre in 1996, and the 1996 War. Then came the targeting of schools in 1999 — they bombed a school in Arabsalim — followed by liberation in 2000. None of these events just fade away. These were the experiences that shaped my choices.

The photographs you saw back then aren’t like the ones you see today. The media today manages their coverage tightly; in the past, they just ran with the raw, unedited material. When reporters arrived at Qana after the massacre, it was horrific — the images haunted you long after the fact. My older sister was a journalist during the occupation, so I’d see her leave for work and return carrying her camera.

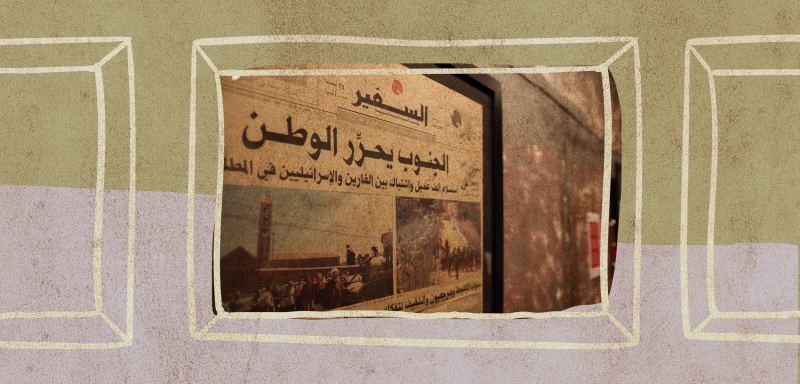

When I moved to Beirut, I kept encountering materials — newspapers and magazines from the South — that caught my attention, so I began buying and collecting them.

What began as a handful of newspapers and magazines has grown into a much larger archive over the last five years, and now contains a wide range of materials: magazine and journals print issues, video and audio recordings. My focus is primarily on the South’s occupation from 1975 to 2000. But post‑2000 conflicts — like the July War in 2006 and the ongoing war today — also form part of the archive.

What began as a handful of newspapers and magazines has grown into a much larger archive over the last five years, and now contains a wide range of materials: magazine and journals print issues, video and audio recordings.

How did you learn how to archive?

I consult with experts, read extensively on the subject, and learn from others’ experiences. Right now there’s a new challenge: the ongoing war isn’t yielding paper — it’s yielding things. Someone brings me a bullet box from Khiam, and suddenly I have twenty boxes. I have a remote control for a rocket launcher, a United Nations helmet from 1978, a rifle “room” salvaged from a shelled home, a sleeping bag retrieved from the ruins — the sleeping bag belonged to the person who was killed there — a live landmine, a watch with its glass melted by a nearby blast, a notice plastered on the wall in Alma al‑Chaab by occupation soldiers to track daily operations. Where do I put them all?

What is your archiving process?

First, I acquire the items. Depending on their condition, I either prioritize them for digitization or, if they’re stable enough, I wait a little longer. Ali Daqdouq, my colleague, helps me. I can’t afford to have someone scanning day and night, so we scan just the covers to know what I actually have — to create an inventory and a database. That way, if someone asks, “Do you have newspaper X from date Y?” I can quickly check if I do.

Then there’s the question of how to categorize the materials, where exactly to keep them, and what boxes to use. For instance, acid‑free boxes are ideal for paper items, but they need a temperature‑controlled environment. Here [in Beirut] isn’t ideal, but my priority right now is protecting each item.

Keys to homes in South Lebanon that have been abandoned during war or destroyed by the Israeli army. Beirut, Lebanon. April 2025. (Photo courtesy of Adeeb Farhat).

Keys to homes in South Lebanon that have been abandoned during war or destroyed by the Israeli army. Beirut, Lebanon. April 2025. (Photo courtesy of Adeeb Farhat).

Keys to homes in South Lebanon that have been abandoned during war or destroyed by the Israeli army. Beirut, Lebanon. April 2025. (Photo courtesy of Adeeb Farhat).

The second challenge — one I’m currently struggling with, and so is [fellow archivist] Amani Ramal — is deciding where to store the archive. My collection is already split across multiple locations because I don’t have the space or storage for everything in one place. That’s the consensus among archivists today: secure the physical integrity of the material first, then figure out the rest.

How have people responded to your project?

I initially collected items from my family, my village, and friends of friends. One day, a former student of mine told me I had to go see a man living in the Nabatieh town of Jebchit, because “he has a huge collection.” I asked him to introduce me, and he arranged the meeting.

When I arrived, I met an elderly gentleman who had turned his home into a private museum. He gave me a tour, showing me his archive and a treasure trove of remarkable pieces. As we spoke — I spent nearly four hours with him — I explained my project to him and what I was trying to do. I asked him if he was willing to give me an item or two from his collection, but I understood if he wasn’t ready to part with anything. He wasn’t; he wasn’t willing to give me anything.

Just when I gave up and got ready to leave, his wife — who had been sitting with us and listening to the conversation — left the room, returning with an item in her hands. There were two identical pieces, one hers and one his: a cigarette box produced by the regie for the South in the 1980s, and the yellow ribbon distributed in solidarity with South Lebanon and the Western Bekaa during the United Nations Security Council Resolution 425. Schools handed out the yellow ribbons across the South as a symbol of solidarity.

“I kept this for my son, but seeing your dedication to archiving, I want you to have it,” she said. Her husband was taken aback, then insisted I take the item I had initially asked for. I took both items and I left, and they’ve since become cornerstone artifacts in the archive.

After that visit, I began approaching complete strangers — people I didn’t know at all — striking up conversations, hearing their stories, and asking if I could take an item. I would then discover a similar item or story in another place, allowing me to connect the dots between them.

How do you incorporate these stories into a singular, cohesive archive?

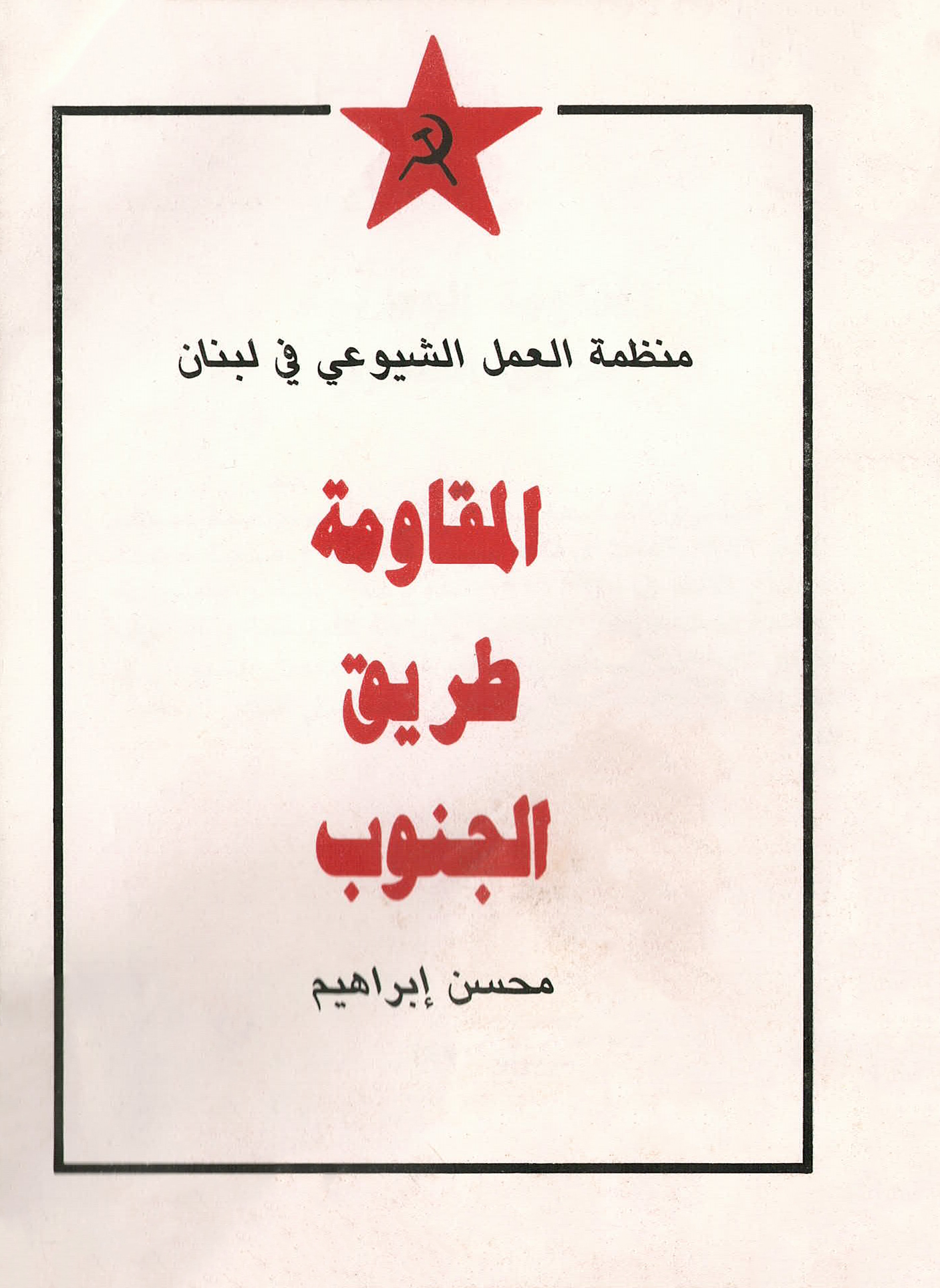

The challenge was, once I had amassed all this material, what should I do with it? I sat with my mentor — my communications studies professor at university, who I deeply respect — and told him about the growing archive: rare documents, multiple narratives. I had been collecting as‑Safir and Al-’Amal newspapers, the Lebanese South Army magazine alongside Al-’Ahad, Hezbollah’s publication—ensuring every voice was represented. I wanted to know, after twenty-five years of liberation, what people were saying back then—every faction’s perspective.

I suggested organizing an exhibition of these archival materials, but he told me, “you could do that, but it’s not what you should be doing.” His words stung. I went away, thinking, “what am I supposed to do with all of this material?”

Shortly after the conversation, I discovered a 1995 document connected to a martyr from my own village. I knew the story already, but if I were to show it to somebody unfamiliar with my village, the young generation who have not experienced occupation, how would they understand its significance and relate to it? I needed somebody who could relay the whole picture. I called a villager who I believed would shed light on the document and the martyred young man. We met at my office and recorded two hours of oral history about the document — his displacement, his family, the South in general, and the occupation.

"Resistance is through the South" (المقاومة طريق الجنوب) published by Mohsen Ibrahim and the Lebanese Communist Party. (Photo courtesy of Adeeb Farhat).

"Resistance is through the South" (المقاومة طريق الجنوب) published by Mohsen Ibrahim and the Lebanese Communist Party. (Photo courtesy of Adeeb Farhat).

"Resistance is through the South" (المقاومة طريق الجنوب) published by Mohsen Ibrahim and the Lebanese Communist Party. (Photo courtesy of Adeeb Farhat).

It turned into a fascinating, intentional experiment. I began contacting everyone I knew. I called Raed Moukalled, because I remembered the story of his son, Ahmed Moukalled, who was martyred in 1999 when an explosive object killed him. Raed and I recorded another two hours—and it kept going from there.

My goal is to assemble a collection of stories. The archive doesn’t rest on physical items alone—it relies on audio recordings and oral histories. A story without its accompanying document lacks credibility, and a document without its story is just a piece of paper. To give life to an artifact buried in a box, you must link it to the narrative it triggers—or vice versa. They complete each other in this way, and that’s exactly what I do: I hunt for a document in the archive, then track down someone who can tell me its story—or I follow a lead until I can find the proof.

A story without its accompanying document lacks credibility, and a document without its story is just a piece of paper. To give life to an artifact buried in a box, you must link it to the narrative it triggers—or vice versa. They complete each other in this way.

Have you noticed, through your archival work, if this ongoing war differs from past wars?

The current war was barbaric. Entire villages were effectively erased — some saw over 50 percent of homes destroyed, others more than 70 percent. In terms of sheer devastation, this has been the worst of all. In terms of displacement, it’s the longest mass exodus we’ve seen. Unlike in 2006 — when only Dahieh and South Lebanon were primarily targeted — every corner of Lebanon was hit this time.

In the months leading up to Israel’s full-scale escalation, since October 8th, all the border villages were already emptied — residents had moved to second‑line towns [north of the Litani River]. Add to that the pagers attack, targeted assassinations, and aerial strikes preceding the full outbreak. On the first day alone, there were 1,500 air raids while people were running around, fleeing.

Israeli occupation soldiers planted bombs and detonated entire neighborhoods. That level of deliberate destruction has never happened before. In 1985, Israel’s “Iron Fist” policy targeted individual villagers suspected of ties to the Resistance — seizing and executing some, demolishing their homes, but they never razed an entire village.

The goal this time is total obliteration.

Based on everything we’ve discussed, how do you select what archival materials to feature? Which materials do you believe must be made public—and why?

I don’t believe anything should be hidden; everything deserves to be public. But it's about how you present it — because the subject is extremely sensitive and hinges on whether it serves the interests of the Southerners. That’s my guiding principle.

I don’t believe anything should be hidden; everything deserves to be public. But it's about how you present it — because the subject is extremely sensitive and hinges on whether it serves the interests of the Southerners.

I archive everything related to the South — I don’t filter what I collect. I filter what I present. The work has two phases: collection and curation. For collection, I gather all available materials. At one point the archive held around 4,000 items — I document absolutely everything I can, but then I start creating a narrative, curation. I choose which pieces to make public and the stories surrounding them. That’s why I believe that the work is political. This selection process is inherently political — deciding which items are accessible to everyone, and which narratives you want to foreground.

A large portion of the archive consists of materials left behind by the occupiers, and these do not reflect our narrative. For example, I have a greeting card an Israeli officer gave to local civilians in 1995 — just one year before the Qana Massacre. How do you frame that? Simply displaying it and marveling, “Look how affable they were!” would be misleading.

Or, for instance, take the photographs of the “Good Fence” in 1977, showing a field hospital on the border treating Southern patients — a year later Israelis invaded and occupied us. It all comes down to context and presentation.

Why is archiving so important to you? What does it mean beyond simply preserving?

It resonates with me on multiple levels—both personal and political. The archive is inherently political; even when you’re preserving something seemingly apolitical—say, music—it remains political because you have consciously chosen to document expressions of identity, customs, community, and a people. It’s always political.

I feel like we never properly dealt with what the occupation left behind in 2000. All the paper materials and objects that remained either vanished or were discarded over time. We generally lack a strong connection to our collective memory. You’ll find someone’s old photographs from their home, or family snapshots in Souk al‑Ahad alongside other personal items — things long since forgotten. From my own experience and from how the authorities treated us — how they suppressed documentation — they wanted us to move on, “it’s over, let it go,” and we were left with the stories they chose to tell.

But, of course, I love storytelling.

The archive is inherently political; even when you’re preserving something seemingly apolitical—say, music—it remains political because you have consciously chosen to document expressions of identity, customs, community, and a people. It’s always political.

How do you manage the emotional weight of this project?

The first time I recorded someone who broke down in tears, I froze. I was interviewing a woman who, as she spoke about her house, suddenly wept. My instinct was to ask, “Shall we stop the recording?”

I have since learned to let them speak through their emotions, to keep recording, and then gently guide them back with my questions.

But some stories are heavier than others.

Rasha's family home in Aita al-Chaab. Aita al-Chaab, Lebanon. May 2021. (Photo courtesy of Rasha Srour).

Rasha's family home in Aita al-Chaab. Aita al-Chaab, Lebanon. May 2021. (Photo courtesy of Rasha Srour).

Rasha's family home in Aita al-Chaab. Aita al-Chaab, Lebanon. May 2021. (Photo courtesy of Rasha Srour).

During the exhibition’s opening this year, an older woman moved slowly among the artifacts, listening to each story. When she knew that I was responsible for the exhibition, she approached me and said, “I’m from Aita [el-Chaab]. My home was destroyed in this war.” She scrolled through her phone, found a photo of her house, showed it to me, and shared her pain. I listened as she spoke on and on — her grief made me think of my own mother’s possible plight.

At the end, she apologized: “I know you’re pleased with today’s exhibit, and I’m intruding on your moment — but I just needed to unburden myself.” A few days later, I asked Ali, my colleague, for her contact details, since they were from the same town. I contacted her and told her that I’m interested in recording her story, and she was very excited. She invited me into her home, I met her daughter, and we recorded her story properly. I even added one of her personal items to the archive, because I felt responsible to preserve her testimony as part of this collective memory.

Since then, visitors at the exhibition — often strangers — approach me and say, “We need you to record our story, too.” Some even contact me via Instagram. I sit with them beforehand, get to know them, schedule a proper session, and only then do I start recording. I omit contributors’ names in my exhibitions — I don’t label any story with a person’s identity, even if they’d like the credit. I explain to them and to visitors why names are withheld: revealing someone’s involvement — say, a former resistance fighter — could endanger them or their children, who might face travel bans or other reprisals.

Which items in the archive are the dearest to you—and why?

Honestly, they’re all equally precious to me. That said, I’m especially drawn to the truly rare items — because the rarer an artifact is, the more I make sure it’s preserved properly, stored separately, and presented so that people who’ve never seen it before can encounter it for the first time, and this is very important to me.

To me, every item is personal — part of my own story. My collection includes Palestinian documents, which I treat as a complementary archive to that of the South. These older materials demand an even greater responsibility: if I or my peers don’t preserve them, who will? That sense of duty — to safeguard every document and testimony — must guide every archivist involved in this work.

My goal is to make everything accessible — for students, filmmakers, researchers — so they can all benefit from this living archive.

Editor’s note: This interview is dedicated to our colleague Rasha’s family and all families in the South who have given up their most valued possessions — and lives — to resist Israeli occupation. We invite you to read this interview and learn more about what people are doing to ensure future generations do not forget what it means to neighbor a state intent on our destruction and erasure.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!