“Since we remember, from the 1970s, Israel has been terrorizing, attacking, and bombing us. But we never lost hope, and we won't lose it now. I still have hope that I will return to my village, to my land, and to the soil I planted in. I want to go back and harvest the olives and laurels my father planted."

These are the words of Um Shadi, who was displaced for the first time with her two daughters from South Lebanon to the southern suburbs of Beirut in October 2023. She was forcibly displaced again to Choueifat, to her son's home, while trying to reconcile between the life she knew just a short time ago and the nightmare of possibly never returning to her border village of Ayta al-Shaab in the Bint Jbeil district, located in the Nabatieh Governorate.

“Do you see what's happening in the South now? It’s like seeing myself again at the age of 14, running barefoot from the Palestinian village of Kafr Qasim. By God, it’s better for a person to be buried in his home. Once Israel forces you to leave, there’s no coming back.”

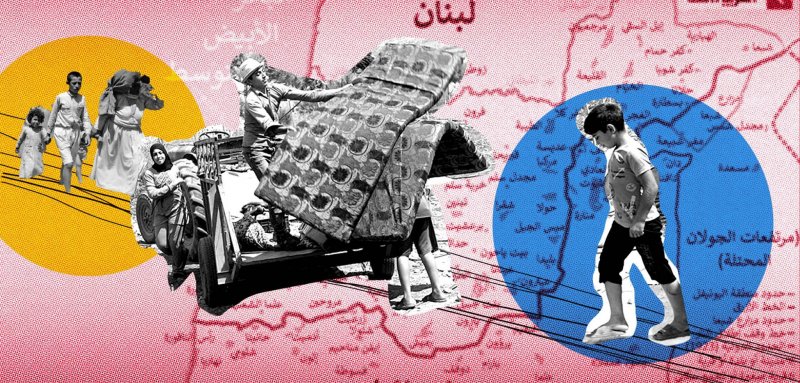

The parallels between the Lebanese displacement from the South in 2024 and the Palestinian displacement in 1948 are strikingly clear, especially to those who lived through the Nakba and are still alive to witness the events repeating today. The evacuation orders, the residents' alarm as they are forced to leave in a hurry with only essential belongings and house keys, a full displacement, and then a long, long wait for an uncertain return—are all echoes of the past.

What happened then and what is happening now feels like pieces of a puzzle coming together, yet no one wants to see the picture fully formed.

Forced displacement in Lebanon

Forced displacement in Palestine

The Green Line and the Blue Line

“Do you see what's happening in the South now? It’s like seeing myself again at the age of 14, running barefoot from Kafr Qasim. By God, it’s better for a person to be buried in his home. Once you leave, there’s no coming back.”

These are the words of Hajjeh Zeinab, a Palestinian woman born in 1942 in the village of Kafr Qasim. This village is located within the Green Line and is infamous for the massacre that occurred there in 1956.

The Green Line refers to the armistice line drawn after the first Arab-Israeli War in 1948, and is also known as ‘The 1967 Border’. The line was demarcated based on the armistice agreements signed in 1949 between Israel and neighboring Arab states: Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. The Green Line represented the boundary between Israel and the Arab states until the 1967 June War, when Israel occupied the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula.

Hajjeh Zeinab recalls that fateful day 68 years ago: "We fled with just the clothes on our backs while men were being slaughtered. We didn’t even realize where we were until we found ourselves hiding among the cactuses outside the village. We had crossed the Green Line. There was a woman who had just given birth, and in her panic, she grabbed the pillow instead of her baby and fled. When she realized her baby was still back in the village, she lost her mind. Her husband insisted on going back to get the baby. She went with him, and when they reached the house and retrieved the baby, a bullet hit the man between his eyes right at the doorstep, and he died. The woman kept crawling with her baby in her arms until she reached the cactuses."

The parallels between the Lebanese displacement from the South in 2024 and the Palestinian displacement in 1948 are strikingly clear, especially to those who lived through the Nakba and are still alive to witness the events repeating today. The evacuation orders, the residents' alarm as they are forced to leave in a hurry with only essential belongings and house keys, a full displacement, and then the long, long wait for an uncertain return—these are all echoes of the past.

Fatima, a young woman from Ayta al-Shaab, shares an experience similar to Hajjeh Zeinab's. Speaking to Raseef22, she says: "I actually wish my house had been bombed and destroyed. I know these are heavy words to say, but that would be easier for me than the idea of the Israelis entering it. I wish I had died in my village and been buried there. That way, whether there’s an invasion or not, I’d be in the soil of my country, and nothing else would matter. I wouldn’t have been displaced or witnessed everything that is happening now.”

Fatima was displaced from the border village of Ayta al-Shaab to Aabbassiyeh, near Tyre, in early October. Two weeks ago, as Israeli airstrikes struck vast areas across South Lebanon, she was forced to leave again, this time to the Mount Lebanon region.

Like her, many people from the South today have fears that history will repeat itself, and that time will take them back to pre-2000, before the Blue Line was demarcated. The Blue Line is a 120-kilometer border drawn by the United Nations after Israeli forces withdrew from South Lebanon.

Below this line lie some of the largest and most important villages in southern Lebanon, many of which we hear about today in the news as they are being bombed. Villages like Maroun al-Ras, Bint Jbeil, Ayta al-Shaab, Yaroun, Kfarkela, Odaisseh, Meiss El Jabal, Rmeish, and Khiam, in addition to the Shebaa Farms and the village of Ghajar, which remains a point of contention over its sovereignty. This line is considered a "temporary boundary" for practical purposes and does not represent an officially recognized international border.

Law professor Ali Murad tells Raseef22: “From a legal standpoint, Israel never sought to annex parts of the South as it did with the West Bank, Gaza, and the Golan Heights, nor did it attempt to establish settlements. In a legal sense, the occupation of the South was temporary, not permanent. But in the political and temporal sense, the occupation lasted 20 years.”

Before the year 2000, the people of South Lebanon were subjected to arrest, abduction, and torture. Today, they are oscillating between the fear of returning to those days or never returning to their homes at all.

Despite the occupation ending in 2000, it left a heavy mark on the collective memory of southerners, reminding them of the hellish life they lived under Israeli occupation.

Abbas Youssef, a Lebanese man from the border village of Jebbayn, recounted how stifling life was during the Israeli occupation of the South before 2000. He described how he had to obtain security permits just to visit his home and how the atmosphere was filled with constant fear of arrest or sudden attacks by the Israeli army or the South Lebanon Army (SLA) militia, locally known as Lahd forces, backed by Israel.

In his interview with Arab American News, Youssef recalled how the people of the South were frequently at risk of kidnapping or torture. He shared the tragic story of a female relative who was arrested after trying to protect her neighbor from an attack by the South Lebanon Army militia. She shielded him with her own body before the militia was finally able to snatch him and execute him out in the open—a tragic experience that shows how dangerous the situation was for the local residents.

Forced displacement in Palestine

Forced displacement in Lebanon

After the separation barrier, buffer zones around Israel, in the north and south

"We stayed up all night watching the news, and the whole time, I kept asking myself, is this what it feels like? Is this how our parents lived through the invasion of 1982? I lost the South, and I feel like I lost Baba all over again, and I’m grieving his flowers. My father rebuilt our house in 2006 after the Israelis destroyed it, but never in a million years did we think they would now take it all.”

Maryam, who shared these words with Raseef22, has been displaced three times—from the South to Beirut’s southern suburbs, and then to Choueifat, then Aley. She, like many southerners, has worries that she may never return to her home in Ayta al-Shaab, as her house—along with thousands of others in nearly 130 villages—received "evacuation orders" from the Israeli army in southern Lebanon. In extremist Israeli rhetoric, these homes are chillingly described with phrases like establishing a "buffer zone" or a “depopulated strip.”

These fears and displacement mirror those of Nourhan from northern Gaza, who spoke in a report for UN Women about her terrifying experience of fleeing her home and the fear of never returning. Despite her determination to stay in her northern Gaza home, when her neighbours’ homes collapsed in airstrikes, she “made the painful decision to leave.”

“Every step I took away from my beloved house was painful,” she said. “I was leaving behind my memories and my dreams.” When she later made a quick return trip in an attempt to collect some of her belongings, she saw how “families were left homeless, and despair lingered on the streets.”

“Since we remember, from the 1970s, Israel has been terrorizing, attacking, and bombing us. But we never lost hope, and we won't lose it now. I still have hope that I will return to my village, to my land, and to the soil I planted in. I want to go back and harvest the olives and laurels my father planted."

A few months ago, American media outlets like The Wall Street Journal and CNN reported that Israel was planning to create a buffer zone inside the Gaza Strip, which would cut off about 16% of the total area of the besieged enclave, especially in the northern regions. According to reports, the plan involved large-scale destruction of infrastructure and buildings in that zone, along with mass evacuations. Many view this as an attempt to unofficially alter borders by establishing a new "safe zone" under Israeli control.

Recently, Israeli statements calling for the re-establishment of a buffer zone in South Lebanon have resurfaced. In September 2024, Israeli Northern Command General Uri Gordin called for the "occupation of part of southern Lebanon to form an Israeli-controlled buffer zone, aiming to push Hezbollah fighters away from the Israeli border."

Gordin argued that this move was necessary to "reduce the threats posed by Hezbollah to northern Israel and ensure the return of thousands of Israelis who were evacuated from border areas after tensions escalated."

Reports from American and Israeli sources also suggest that Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant has discussed this idea with the Israeli military leadership, justifying it as a way to secure Israel’s northern border against Hezbollah attacks.

These proposals, which face opposition within the Israeli army itself, come at a time when the civilian population in southern Lebanon has significantly decreased, with estimates suggesting that only 20% of the population remains in their villages. According to Israeli leaders, this would make the military operation faster and easier to execute.

On the military level, the head of the Israeli army's Northern Command, General Uri Gordin, is one of the strongest advocates for establishing a buffer zone carved out of southern Lebanon, while Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant is its most prominent supporter in the political arena.

The second objective of creating this buffer zone, according to Israeli sources, is to use it as a bargaining chip in potential negotiations with Hezbollah, where both sides might reach an agreement to withdraw Israeli forces.

However, opinions are divided within Israeli leadership regarding this plan. Some commanders fear it could lead to a much larger war with Hezbollah, further complicating the region's security situation.

According to Honaida Ghanim, Director of the Palestinian Center for Israeli Studies (MADAR), “It’s extremely difficult to predict what might happen, but it’s clear that Israel has dismantled and disregarded all international laws and restrictions. We now have a mixture of euphoria and a sense of power, alongside a wide margin for action, all in the absence of any real or serious international pressure forcing it into a political agreement. Given the current atmosphere in Israel, which can be described as freedom of military action, I wouldn’t be surprised if people are forced out of their villages and prevented from returning. I wouldn’t rule that out at all.”

Some analysts from Lebanon and Palestine believe that repeating the scenario of evacuating northern Gaza in southern Lebanon is unlikely, due to several factors, particularly historical ones, and the differing military and political situations.

Speaking to Raseef22, Ghanim adds, “The Israeli environment is pushing in that direction, and we are in a very dangerous stage. However, how things will unfold in the coming days depends on decisive factors that have yet to occur, such as the nature of the confrontation with Iran or the possibility of reaching an agreement in the near term. Based on that, the relationship with Lebanon and the region will be rearranged. But if Israel continues in this current manner, I wouldn’t be surprised if it tries to create a depopulated buffer zone, and that this situation will continue for many years.”

Map of villages in South Lebanon below the Litani River

But the South isn’t Gaza!

“I mean, a person doesn’t know how to feel, what to do, or what to say. I can’t even imagine the idea that we might never return. It’s hard to stay optimistic with everything happening, and what’s even harder is the frustration and despair that tries to overwhelm you completely.”

That’s how Zainab, who is a mother to one boy, describes her feelings after she and her family fled from a border village to the village of Tebnine last October, then to Haddatha, and three weeks ago, after the bombing intensified, they fled a third time to Hamra in Beirut. They spent a few nights on the streets before moving to a shelter in Mount Lebanon.

With news headlines repeatedly mentioning a “Gaza scenario in Lebanon” and with a history full of displacement, occupation, and massacres endured by those neighboring Israel, Zainab’s frustration and despair don’t seem exaggerated. However, some political analysts don’t believe a scenario of displacement or occupation is likely.

One of these analysts is Palestinian thinker and writer Hassan Khodr, who tells Raseef22: “It’s important to always think the way the Israelis do: 'The best permanent solution is the temporary one.' They are in the process of experimenting with more than one temporary solution to the current situation. But the reality now is different from what it was in 1948.”

Khodr adds in his conversation with Raseef22: “There is no consensus among Israeli decision-makers about the ‘day after’ in Lebanon. The preference for one option over another depends on the results of the fighting on the ground. However, there is a serious Israeli tendency and inclination to hold onto land in Gaza and southern Lebanon, based on the belief that the most powerful deterrent is making the enemy lose territory if they cross the line. This view resonates among settlers, but the military is against this move for economic reasons.”

"We fled with just the clothes on our backs while men were being slaughtered. There was a woman who had just given birth, and in her panic, she grabbed the pillow instead of her baby and fled. When she realized her baby was still back in the village, she lost her mind. She and her husband insisted on going back to get the baby. When they reached the house and retrieved the baby, a bullet hit the man between his eyes right at the doorstep, and he died. The woman kept crawling with her baby in her arms until she reached the cactuses."

Lebanese journalist Daoud Rammal shares this view. He says: “In my opinion, these Israeli threats are tied to the political conditions that Netanyahu had previously communicated to US envoy Amos Hochstein, who, in turn, conveyed them during his visit to Lebanese officials. The Israeli side has expressed willingness to implement Resolution 1701 ‘plus,’ meaning there are additional security arrangements involved. These arrangements are not limited to making the area south of the Litani River free of weapons and Hezbollah, except for the Lebanese army and UNIFIL. Israel wants the entire South, up to the Awali River, to be weapon-free, covering a depth of 50 kilometers. The Lebanese side rejected this, insisting on implementing Resolution 1701 and returning to negotiations to stabilize the land borders.”

He adds: "Yes, we have reached a different stage now. What is happening today can be likened to 1982 during the Israeli invasion, but without Israel advancing on the ground to occupy Beirut. Now, it is occupying by fire—whether through air or sea control—having brought its naval forces into the battle. Warships are bombing the southern suburbs alongside airstrikes. I believe that once foreign countries complete the evacuation of their citizens from Lebanon, we will see an air blockade on flights from Beirut Airport. It has become clear that this escalation aims to push the international community to exert pressure on Lebanon to accept a significant portion of Israel’s terms. I don't think Lebanon will accept this, because any agreement outside of Resolution 1701 would transfer the problem internally, and Lebanon cannot bear the consequences like those after the 2006 war—protests in Beirut, tent sit-ins, which lasted for almost two years, then the events of May 7, and the eventual move to Doha. What Lebanon needs now is a swift Arab initiative, with Western support, led by France, which has a deep interest in the Lebanese issue, both humanitarian and political, to bring Lebanon back into the Arab fold, reduce Iranian influence in decisions of war and peace, and secure international backing for economic recovery and reconstruction."

According to various confirmed reports and multiple sources, the area stretching from the Lebanese border to 15 kilometers north has become almost empty of inhabitants, bringing the desired scenario closer for the Israeli groups advocating for settlement in southern Lebanon.

He concludes: "The ball is now in Israel’s court. No one knows the timeline the West, led by the United States, has given Netanyahu to continue his military operations in Lebanon. Some say six weeks; others believe it could drag on, as it did in Gaza. We hope it won’t last long and that a solution is reached to preserve Lebanese stability, as any imbalance in the resolution will lead to a severe Lebanese crisis—which, I believe, is exactly what Israel wants."

Forced displacement in Lebanon

Areas emptied of weapons, or of its people?

The Litani and Awali Rivers lie in South Lebanon, but they are far from the southern border with Israel.

The Litani River originates in western Beqaa and flows south through the Beqaa Valley, then turns west to empty into the Mediterranean Sea. It is about 20 to 30 kilometers from the southern border at its closest point and gained its political “fame” due to its association with Resolution 1701.

"I actually wish my house had been bombed and destroyed. I know these are heavy words to say, but that would be easier for me than the idea of the Israelis entering it. I wish I had died in my village and been buried there. That way, whether there’s an invasion or not, I’d be in the soil of my country, and nothing else would matter. I wouldn’t have been displaced or witnessed everything that is happening now.”

The Awali River, located near the city of Sidon in southern Lebanon, is shorter in width than the Litani but lies 35 to 40 kilometers from the border.

These two rivers play an important role in the military strategies being studied by Israel. The Litani is often proposed as a reference point in Israeli plans to push Hezbollah away from the northern border. However, the recent appearance of the Awali River as a new dividing line in Israeli statements reflects a significant shift in the area they aim to clear of weapons at best, and of people at worst.

Recently, several calls have emerged from Israel to establish a buffer zone on the Lebanese border. Among them are military calls, the most prominent of which is from General Uri Gordin, who has demanded the creation of a buffer zone to push Hezbollah forces beyond the Litani River.

Mixing the cards is a well-known game in Israeli politics, like mixing the killing of civilians with combatants, and mixing the concepts of buffer zones, demilitarized zones, and depopulated zones until they become a reality. For instance, Israeli statements at the beginning of the ground invasion of northern Gaza, coinciding with evacuation warnings, claimed that the goal was to eliminate Hamas and then return the population to the north. However, today, the depopulation of northern Gaza has become a reality, and settlement plans around the Gaza Strip are slowly being leaked. So what guarantees a different reality for southern Lebanon?

However, military demands pose no real threat unless they gain political backing. One of the leading political figures advocating for the depopulation of southern Lebanon, both of weapons and people, to establish this buffer zone is Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant.

Mixing the cards is a familiar and well-known game in Israeli politics, like mixing the killing of civilians with combatants, and mixing the concepts of buffer zones, demilitarized zones, and depopulated zones until they become a reality. For instance, Israeli statements at the beginning of the ground invasion of northern Gaza, coinciding with evacuation warnings, claimed that the goal was to eliminate Hamas and then return the population to the north. However, today, the depopulation of northern Gaza has become a reality, and settlement plans around the Gaza Strip are slowly being leaked. So what guarantees a different reality for southern Lebanon?

According to various confirmed reports and multiple sources, the area stretching from the Lebanese border to 15 kilometers north has become almost empty of inhabitants, while many residents of the villages have begun to voluntarily displace themselves further north, bringing the desired scenario closer for the Israeli groups advocating for settlement in southern Lebanon.

"We stayed up all night watching the news, and the whole time, I kept asking myself, is this what it feels like? Is this how our parents lived through when the invasion of 1982? I lost the South, and I feel like I lost my father all over again, and I’m grieving his flowers. My father rebuilt our house in 2006 after the Israelis destroyed it, but never in a million years did we think they would now take it all.”

Israeli warning telling residents of vast regions in the Beqaa to leave their homes and villages

"A cedar surrounded by the Star of David": What is the Uri Tzafon movement?

One of the prominent settlement movements advocating for the establishment of "Greater Israel" in South Lebanon is the Uri Tzafon movement, which is using the symbol of a cedar tree surrounded by the Star of David. According to one of its founders, Eliyahu Ben Asher, the movement promotes the importance of fighting to revive "Lebanon as a prosperous Jewish homeland, as part of Greater Israel," and as a first step to the borders of Turkey and Iraq. The movement's members have been entertaining themselves by sending drones to South Lebanon, demanding that residents leave because "this is the land of Israel."

The Uri Tzafon Movement to settle Lebanon

According to Israeli sources, this movement is rapidly growing and was founded in memory of Yisrael Sokol, an Israeli soldier killed during fighting in Gaza in January last year. According to his family, Yisrael didn’t dream of Israeli settlements in Gaza but in Lebanon.

In pursuit of their extremist religious vision, the Uri Tzafon movement is a prominent settlement movement advocating for the establishment of "Greater Israel" in South Lebanon, while using the symbol of a cedar tree surrounded by the Star of David. The movement's members have been entertaining themselves by sending drones to South Lebanon, demanding that residents leave because "this is the land of Israel."

Yaakov Sokol, Yisrael's brother, mentioned in an interview: "There was a joke between Yisrael and me that we would live in Lebanon, but the joke was always serious. It’s the land that should be in our hands."

After Yisrael's death, Amos Azaria, an active professor in the growing movement to reestablish Israeli settlements in Gaza, spoke with the Sokol family about how to realize Yisrael's dream, leading to the establishment of the Uri Tzafon movement. In the few short months since its launch, the group has grown at an unprecedented rate, with its official WhatsApp forums now including more than 3,000 members from all over Israel.

In these virtual spaces, leaders regularly exchange images of explosions in northern Israel and Lebanon; they share detailed criticisms of Israel’s supposedly ‘lenient policies’ in the region, suggest Hebrew names to replace existing Lebanese town names, and advertise future rafting trips in South Lebanon with the slogan: "It's not a dream, it's reality!"

In the few short months since its launch, the Uri Tzafon movement promoting the settlement of Lebanon has grown at an unprecedented rate, with its official WhatsApp forums now including more than 3,000 members from all over Israel. It was founded in memory of Yisrael Sokol, an Israeli soldier killed in Gaza who didn’t dream of Israeli settlements in Gaza, but in Lebanon. Yisrael's brother mentioned in an interview: "There was a joke between Yisrael and me that we would live in Lebanon, but the joke was always serious. It’s the land that should be in our hands."

A Palestinian historian from Haifa commented on the emergence of these groups, saying: "There is a belief among large segments of Jews and Israelis—whether they are religious and adhere to the Torah's literal text, or secularists from the right in its various forms—that Lebanon is part of the land promised by God to the chosen people. This belief is rooted in several Torah texts, including the Song of Songs, Ezekiel, and Deuteronomy. They consider the high mountains of Lebanon to be parallel to Jerusalem and the lower mountains of the Promised Land. In addition, the relationship between King Solomon and Hiram, King of Tyre, was close due to their mutual interests, most notably trade. Lebanon's cedar trees are mentioned in the Torah as the finest, and they are all seen as gifts from God to His people."

The Torah specialist adds to Raseef22: "Accordingly, considering Lebanon as a continuation of the Promised Land, as they claim, pushes them to adopt the idea of expelling the 'aggressor peoples,' who have no right to exist on the land of Lebanon because they are foreign peoples (Goyim). To them, the ‘chosen people’ must evacuate and seize the villages and cities, then either destroy them or benefit from them. This religious doctrine was strongly applied in 1948, and now the same doctrine is being discussed concerning Lebanon, at least in the southern region of the Litani River, thus connecting the text with plans for expansion, seizure, occupation, and expulsion."

He adds: "We are facing a project to legitimize the Jewish right in Lebanon and work towards evacuation—a forced uprooting—in order to bring in settlers, thereby achieving the salvation (Yeshua) of the land from the foreigners who ‘corrupted’ it."

In the virtual spaces of Israeli movements to settle Lebanon, leaders regularly exchange images of explosions in Lebanon and share detailed criticisms of Israel’s supposedly ‘lenient policies’ in the region. They also suggest Hebrew names to replace existing Lebanese town names and advertise future rafting trips in South Lebanon with the slogan: "It's not a dream; it's reality!"

However, Rammal concludes with a different political perspective, saying: "The situation in the South is entirely different from that of Gaza, and it differs from the displacement of Palestinians in 1948 or 1967. Israeli threats related to pushing the southerners away from their cities, towns, and villages to the north of the al-Awali River are reminiscent of the same threats Israel made before the 1982 invasion. These are not new threats, and the possibility of Israel seizing and annexing Lebanese lands is unlikely. The Israelis know they cannot get stuck in the Lebanese quagmire again and repeat the same experience that cost them dearly throughout the occupation of the borders from 1978, followed by the expansion of this strip in 1982, which extended until May 25, 2000."

The Uri Tzafon Movement to settle Lebanon

Gradual depopulation of residents

Initially, since September 23, Israeli evacuation warnings, posted by the Israeli army spokesperson on his platform on X, were general and did not name specific villages. The spokesperson merely urged residents to stay away from any Hezbollah facilities or weapons depots they knew of, as the army would target them. This seemed to be a tactic to monitor escape points and then strike them.

"There is a belief among large segments of Jews and Israelis—whether they are religious and adhere to the Torah's literal text, or secularists from the right—that Lebanon is part of the land promised by God to the chosen people. They consider the high mountains of Lebanon to be parallel to Jerusalem and the lower mountains of the Promised Land. Lebanon's cedar trees are mentioned in the Torah as the finest, and they are all seen as gifts from God to His people."

The tone of Israeli orders to the residents evolved on September 24, shifting from evacuation to stern warnings against returning to their homes. Later, on the 28th of the same month, specific areas were mentioned, including the southern suburbs of the capital Beirut, the South, and the Beqaa. By September 30, Israeli warnings began specifying certain locations, with the first warning urging residents near Laylaki, Haret Hreik, and Burj el-Barajneh to leave those areas.

The army then began releasing specific aerial images urging residents to evacuate and leave. Notably, these images were exclusively focused on the southern suburbs ‘Dahyeh’, while the villages and towns received full evacuation warnings without specific or pinpointed locations.

"Considering Lebanon as a continuation of their Promised Land pushes them to adopt the idea of expelling 'the peoples who have no right to exist on the land of Lebanon' because they are foreign peoples (Goyim). To them, the 'chosen people' must evacuate and seize the villages and cities, then settle in them. This religious doctrine was strongly applied in 1948, and now the same doctrine is being discussed concerning Lebanon, at least in the southern region of the Litani River, thus connecting the text with plans for expansion, seizure, occupation, and expulsion."

On October 1, Israeli spokesperson Avichay Adraee issued the first clear warning, calling on those who had left areas south of the Litani River not to return "for their own safety." On the same day, the names of dozens of southern villages began to be listed, eventually totaling 125 villages and towns, with some expecting the numbers to grow. Today, the following villages are almost deserted of their residents in Lebanon:

Yaroun, Ain Ebel, Maroun al-Ras, At Tiri, Haddatha, Ayta al-Jabal, Jmaijmeh, Toul, Deir Aames, Burj Qallawiyah, El Bayada, Chamaa, Zebqine, Jbal El Botm, Srobbine, Sha'aytiyah, Kniseh, el-Henieh, Maarakeh, Ghandouriyeh, Deir Qanoun, Malikiyet El Sahel, Burj el-Shemali, Ebel El Saqi, Srifa, Deir Qanoun al-Nahr, Abbasiyyeh, Al Rashidiya, Bint Jbeil, Aitaroun, Bayut al-Siyad, Ma'shuq, al-Buss, Chabriha, Tayr Debba, al-Barghliyeh, Qasmiyeh Camp, Nabi Qassem, Burj Rahhal, Ain Baal, Mahrouna, Bafliyeh, Deir Kifa, Arzoun, Derdghaiya, Dahr Barriet Jaber, Jebel el-Aadas, Chehour, Sammaaiyeh, Bazouriyeh, Mazraat Sheddit, Marwahin, Chihine, Umm al-Tout, Oum Touteh, al-Bustan, Zalloutiyeh, Yarine, Dhayra, Matmoura, Jibbain, Tayr Harfa, Abi Shash, Alma el-Chaab, Naqoura, Ain Chamaa, Ras al-Bayada, Majdal Zoun, Mansouri, Qsaybeh, Mazraat Beit el-Sayed, Dounine, El Tamriye, Majdal Selm, Qoussair, Aadchit El Qsair, Deir Seryan, Deir Mimas, Qlayaa, Houla, Meiss El Jabal, Bleida, Mhaibib, Chaqra, Baraachit, Qabrikha, Kounine, Ayta al-Shaab, Ramyeh, Yater, Qaouzah, Beit Lif, Hanine, Rachaf, Aynata, Qlaileh, Haouch, Nabaa, Touline, Khiam, Kherbeh, Kfarhamam, Aarab El Louaizeh, Jisr Abu Zable, Kafra, Rmadiyeh, Markaba, Rab El Thalathine, Tallouseh, Taybeh, Qantara, Froun, Haris, Tebnine, Deyrintar, Rechknanay, Seddiqine, Qana, Hanaouay, Aaitit, Maisat, Houmayri, Bistita, Beit Yahoun, and Bani Haiyyan.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!