This piece is part of Beirut Without Windows, a Raseef22 series, made possible through a grant from QARIB project led by CFI and funded by AFD and

Beirut’s madness can only be tamed by its writers. Gibran Khalil Gibran confesses in his first book in English, The Madman, published in 1918 in New York, “I have found both freedom and safety in my madness; the freedom of loneliness and the safety from being understood, for those who understand us enslave something in us.”

Indeed, the essence of our narratives, appearing daily in newspapers and novels, reveals the experience of madness in a city of non-readers. Think of all the diasporic Lebanese authors, living in Brazil, New York, Paris, or elsewhere, when they wrote about the 1975 civil war, did they care that Beirut will never read them?

But, more importantly, why would the hungry beggar on the street care that someone will take notice of his misery and transform him into a protagonist in their book? How about the distracted saleswoman with the empty shelves selling nothing other than expired peanuts? In between her suicidal thoughts and religious revelations, does she dedicate time to reading an article about how to maintain mental stability in an unstable city?

A public history with no owners, as Mahmoud Darwish asserts, is open to whoever wishes to inherit. Beirut has no history without its authors; thus, when they write, they engage in commemorating memories. But one could ask, who is their reader?

“But let me not be too proud of my safety,” Gibran continues, “Even a Thief in a jail is safe from another thief.” Are we, the writers of Beirut, imprisoned by our thoughts on safety, or worse, have we become as safe as thieves are? Writers mummify history, and in Beirut, a city without readers, there are no consequences for those who fabricate the truth.

A public history with no owners, as Mahmoud Darwish asserts, is open to whoever wishes to inherit. Beirut has no history without its authors; thus, when they write about the war, the economy, the revolution and publish in foreign cities, they engage in commemorating memories. But one could ask, who is their reader?

They write about Beirut over and over again, but we do not read them, do we? We are not a community of readers. We are a community that depends on distractions for survival, and books are the worst distraction. Words present experiences we are trying to forget.

“Even sadness was also something for rich people, for people who could afford it, for people who didn't have anything better to do. Sadness was a luxury.”

With the rise of the visual culture and social platforms, we have become disappointed with the written word. We do not read, but if we were to read, we only care for jokes and crosswords.

As I write today for nonreaders, I recall the words of Kamal Salibi, “Lebanon today is a noncountry” (A House of Many Mansions, 1988). It is not an accusation when we declare that Lebanon has failed as a country. But, let us not forget I can write as I wish. Who reads?

Literature in the Arab world is perceived as a privileged medium of expression. It is for people who can afford time and contemplation. For the past couple of years, I have been reciting to strangers the words of the Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector, when she writes, “even sadness was also something for rich people, for people who could afford it, for people who didn't have anything better to do. Sadness was a luxury.”

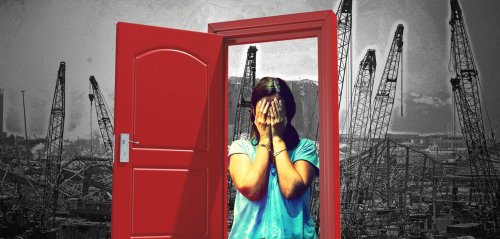

However, nowadays, at last, we have time to be sad. With the pandemic forcing us to stay at home, we are finally unfolding the memories we tucked away in drawers along with photos, letters, and bullets. Who are we, and what have we become? We are 69 prisoners who escape, steal a taxi, crash into a tree, and die.

This reminds me of the last scene in Lispector’s novella, The Hour of the Star (1977) when Macabéa visits a fortuneteller who predicts she will be rich and happy, then when she leaves, a yellow Mercedes runs her over. We are prisoners who escape for our mothers to hand us over to the police again. There is freedom in jail, my son.

Before the lockdown, I was searching for a bookcase to buy. I went from store to store, and as I expected, none of them were selling any. Although one store was displaying three but did not know what they were for. I decided to ask a carpenter to build me one, and as I spoke to him on the phone, describing the kind of wood I would like, he confessed that he was a reader once when he lived in Australia.

I knew where the conversation was heading. He said he has no time to read because as our world is collapsing around us, who has time to worry about books? Even the reader has become a non-reader in a city where buying lemons are a luxury. If lemons now cost triple as much as they used to, books now cost four times the older price. We were uneducated once, now we will be ignorant forever.

Nowadays, at last, we have time to be sad. With the pandemic forcing us to stay at home, we are finally unfolding the memories we tucked away in drawers along with photos, letters, and bullets.

How else do corrupted governments continue to control the people? I never thought of books as a luxury, but Beirut has a way of making you unlearn things. It is a challenge to write without a reader. Are we going mad?

I am drinking tea in a mug that says, “Trust in God – she will provide.” Where is Jean-Paul Sartre when we need him? In a lecture given in 1946, Sartre deliberates that those born as cowards can do nothing about it, and the same goes for those born as heroes but, the existentialist believes that people make themselves whatever they wish. There is always a possibility for a coward to make himself cowardly and for the hero to stop being a hero. To the non-reader, I ask, who do you wish to be?

I will conclude this article with a quote from another Brazilian author, “The work itself is everything: if it pleases you, dear reader, I shall be well paid for the task; if it doesn't please you, I'll pay you with a snap of the finger and goodbye.” Machado de Assis

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!