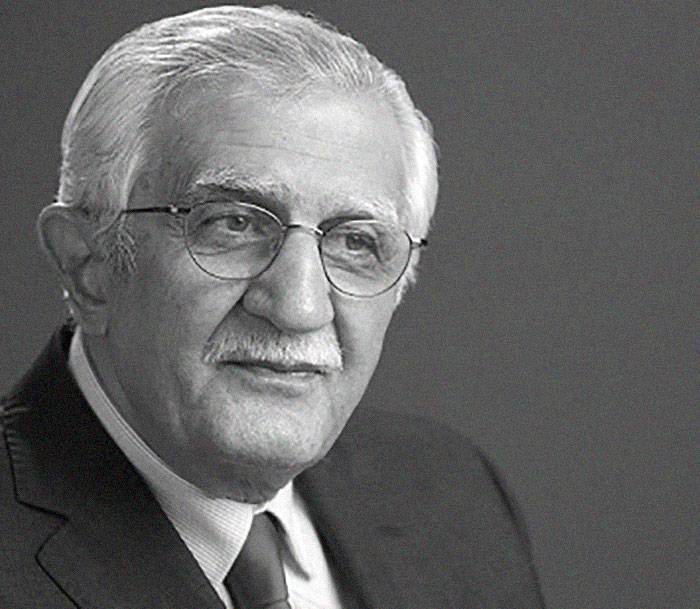

In 2005, I met Ahmed al-Safi, the representative from the office of the Shia religious authority Ali al-Sistani in a conference hall in Baghdad. This was my second meeting with him; my first took place in Syria years earlier, in which we had an intense debate around the reformist opinions (in both Islamic jurisprudence and theological doctrine) of Mohammed Hussein Fadlallah.

Ahmed al-Safi

In Baghdad, I was a reporter for the Iraqi Alhurra TV channel, and specifically the program "Iraq Decides" which covered the sittings of the constitution-drafting committee. Al-Safi was a member of the committee. I intercepted him as he was leaving the meeting hall. I don't know if he remembered our first meeting, but I stopped him nonetheless to ask him of his opinion on whether religion should be a basis of legislation, the main basis of legislation or the only basis of legislation. His answer sufficed by stating that the constitution would not legislate for anything that contradicted Islam, and that the members of the constitution-drafting committee were keen to preserve the Islamic identity of Iraq.

A short while later, I saw the parliamentarian Diya al-Shakarji, then of the ruling Dawa party, sitting in a café at the Council of Representatives. I went to share with him what I had heard. He responded: "The brothers are still preoccupied with Islamic identity, the basis and fundamentals of Sharia, Ashura [the tenth day of the Islamic month of Muharram, on which Husayn bin Ali, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad and a major figure in Shia doctrine, was killed] and the marja'iya [Shia religious authority and point of reference] in the constitution, while the Kurds achieve what they want from tangible gains." Al-Shakarji presents himself as a moderate Islamist, still undecided on many theological arguments, something we often criticized him for; however he would not wait for too long, for soon afterwards he adopted a new path of criticising the term "moderate Islamist."

Diya al-Shakarji

Al-Safi represented al-Sistani in the constitution-drafting committee. The leader of the religious institution had dispatched two representatives to the committee, who were the candidates of the 'United Iraqi Alliance' (known by its electoral number 169 and the symbol of a candle) in the elections of the Transitional National Assembly. Both of them won a seat as part of the 'closed lists' voting process. The other representative was Ali Abd al-Hakim al-Safi, the strongest representative of the Shia religious center of Najaf in Basra.

One of the most powerful and influential Twelver #Shia authorities and the head of knowledge in Najaf, Sistani is the spiritual leader of Iraqi Shia and one of the most senior clerics in Islam, a man of many hats at the centre of the region's politics.

I stopped Safi to ask him his opinion on whether religion should be a basis for #Iraq's constitution, the main source of legislation or the only source. His answer was: the constitution would not legislate for anything that contradicted Islam.

Hopefully, I Will Emerge Alive

The political Shia leaders seem to have benefited from this process, so that they did not have to return every time to al-Sistani when they had a question. I remember here the words of the famous Kurdish politician Mahmoud Othman about the Shia politicians during 2003-2004, whereby he said that they would come to an agreement and then back out because they hadn't consulted Sistani. They seem to have abided by an old Iraqi maxim: "Throw it on the scholar, and depart from it safely."

History however records that the politicians would later rebel against the marja' – the religious Shia authority and 'source of reference to follow'. The disagreements between the marja' and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki would escalate into major difficulties. This is understandable: al-Maliki, with his known dictatorial tendencies and attempts to become a 'Shia Saddam' does not want a marja' to have to return to. Meanwhile, al-Sistani, with his long and broad inherited legacy and the inheritor of the 'shadow' Shia state, cannot allow anyone to supplant their importance as the representative of the occulted Shia imam – even if the adversary here was a politician who also considered himself to be filling in for the political leadership of the missing imam. The Najaf marja' aims to make sure that no one challenges it, even the Iranian Supreme Guide Ali Khamenei, who in turn also rejects his Najafi competitors.

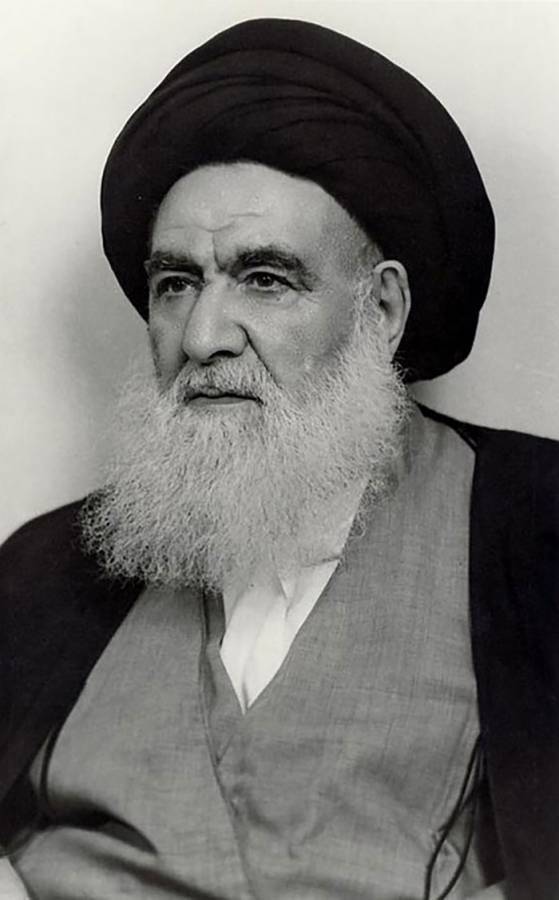

For example, Abu al-Qasim Khoei, one of the most notable jurisprudents and scholars of Najaf, was not in agreement with his Iranian counterpart and leader of the 1979 Islamic revolution, Ruhollah Khomeini. Those who lived through the Shia experience of the 1980s and 1990s remember well how the regime of the 'Vilayet-e Faqih' – the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist established by the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran –maneuvered its tools and proxies against the Shia religious center at Najaf. Amongst these tools were Iraqi opposition figures such as the leader in the Supreme Council, Sadr al-Din al-Qabanji, who often accused Khoei of treachery: an accusation which resulted in a physical attack against him by new Iraqi migrants to Iran who were followers of Khoei in 1991 or 1992.

Abu al-Qasim al-Khoei

In the mid-1990s, the Iranian newspaper Kayhan reluctantly published the photo of Ayatollah al-Sistani as a successor to other major former Shia clerics. Of course, neither Kayhan or the decision-makers in Tehran were able to make a selection. There is a wide network that determines who the replacement will be, one which is not only concerned with matters of Islamic jurisprudence, but is also based on financial, religious and institutional interests.

Al-Khoei and Al-Sistani

Al-Sistani would succeed and become the main Shia marja', despite the strong and effective challenge he faced from different sides, not least by Mohammad Sadeq al-Sadr, who was assassinated in 1999 allegedly by the Saddam regime. However, the new marja' wasn't as effective as he should have been, especially because he emerged during an era of strong competition, while his predecessor al-Khoei was of great esteem and stature; doubts were also raised surrounding al-Sistani's aptitude when it came to matters of jurisprudence.

Najaf: the Hub of Politics

The year 2003 would witness a major transformation. Najaf became an important destination for the visits of politicians and international emissaries. The United Nations diplomat, Lakhdar Brahimi, was a regular visitor. It soon became clear that many important decisions in the country were issued from this religious city, and not from Iraqi's capital. The religious institution advocated for peace, by contrast to the two main Iraqi war parties: Muqtada al-Sadr, who was possessed with the idea of war and resistance, and the Sunni social centers of decision-making, which did not align with the changes introduced by the US occupation and carried up weapons, considering it a form of resistance. Then emerged Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq, who sought to present himself as the representative of the resistance to the US occupation, but would in fact become the master of violence and terrorism.

The Americans lacked the capacity of choices. The increasingly influential al-Sistani waved the olive branch and sought to prevent non-Sadrist Shias from participating in an armed confrontation with the US forces. The cost was exorbitant: accepting rushed elections without any transitional period which would give Iraqis the opportunity to understand democracy, as the marja' wanted. The elections were held, the Shia voter chose those who were close to the Najaf marja', while the Kurd went to those who achieved what they could from the dream of a Kurdish state – i.e. the autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Meanwhile, the Sunni voter was subject to threats and intimidation by al-Qaeda, and consequently boycotted elections and later the constitutional referendum.

Yet the question remains, what has al-Sistani established for his role in terms of jurisprudence and theological doctrine? From a general overview, we find that he did not establish much in theoretical terms. There are not enough writings to understand what he wanted or what he wants now. There are behaviors, attitudes, and actions that are left open to interpretation and for theories to be derived from by readers, researchers and scholars. The cunning religious marja' left things open without explanation. This was an ideal way to protect the marja' from having to declare a doctrinal, jurisprudential or intellectual position that embeds its religious attitude in politics, forcing it to abide by it permanently.

Al-Sistani inherited the two-century old school of 'imitation', i.e. the school which the 'masses of the Shia' go to in Najaf to learn the Sharia, as well as to pay their obligatory Shia alms (known as the Khums – a fifth of their excess income after expenses). In practice however, the marja' does intervene directly in public and political life. It soon accrued the influence of determining whether a prime minister is suited to continuing in power or not. Thus, the marja' helped to bring down Nouri al-Maliki, while retaining his successor Haider al-Abadi, and today it has given a green light for the resignation of Adil Abdul Mahdi.

An Elastic Doctrine

This religious marja' resembles the Islamist forces that accepted democracy after once viewing it as forbidden, without offering intellectual or theological-doctrinal approaches. It is a marja' that struggles to retain its influence and stature and its desired political goals – whether in answering the demands of a boiling revolt on the streets, or even if there were no protests or uprising. It does not offer a strong intellectual foundation, but instead leaves such matters open to flexible variables, thus becoming pragmatic in both thought and doctrine.

The Najaf

Thus, the Najaf marja' possesses an elastic political doctrine: depending on the situation, its role can be as one reduced to silence, or one resembling that of the Iranian Supreme Guide himself – almost like that of a prophet. It is a very exhausting mission for anyone seeking to understand it. It wants those who follow it to remain ignorant about its main authorities, competencies and jurisdictions. Perhaps some of these can surprise observers, while at other times can be less than expected.

It is a political action, a tactic marked by intelligent flexibility – but it is costly for Iraqis who have forsaken coincidences. Equally, they may expect much, only for little to arrive, and they may only seek little, only for much to come. In the current moment, the marja' is associated with Iranian policies as well as the Sadrist movement – the former led by Qasem Soleimani, who benefits from everything al-Sistani says, and the latter led by Muqtada al-Sadr, who claims that he is in harmony with the marja'; in practice however, he is of an orientation different from that which presides in Najaf.

There also lies the problem of how jurisprudence and doctrine are taught in traditional schools. Here, they leave hardly a trace – for one can find many books and opinions on bathroom hygiene, but addressing political positions and national affairs remain scarce.

From one angle, it could be said that this is a positive reality: for it is an effective recognition by the traditional religious institution that it should not intervene in addressing these matters, while political Islam does intervene. Practically however, the scholar of the marja' does interfere, carrying out certain tasks, calling for the application of things, and holding meetings. The student meanwhile does not find something to discuss, because what is present is a set of unstructured actions.

Today, with an ongoing Iraqi uprising, controversy surrounds the position of Najaf. It appears that the marja', or to be more specific al-Sistani and his institution, headed by his son Mohammed Reda, seeks to preserve itself first and foremost, and to repair its reputation which has somewhat deteriorated. For the future of the entire religious institution is on the line.

The marja' also seeks to prevent infighting and belligerency, as this certainly contradicts the heritage which states that the historical Shia Imams, with the exception of Imam Ali and his son Husain, were not armed and did not ask their followers to carry arm. At the same time, the marja' does not want to cause the Shia political class to lose everything. It is trying to achieve the possible goals according to the same flexible methodology which is open to all possibilities.

Whatever the path is, one thing is for sure: the marja' of 2005 that heavily encouraged people to vote in elections, even if that meant death by Zarqawi, is not the same as that of 2019.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!

Join the Conversation

Karem -

1 day agoدي مشاعره وإحساس ومتعه وآثاره وتشويق

Ahmed -

5 days agoسلام

رزان عبدالله -

6 days agoمبدع

أحمد لمحضر -

1 week agoلم يخرج المقال عن سرديات الفقه الموروث رغم أنه يناقش قاعدة تمييزية عنصرية ظالمة هي من صلب و جوهر...

نُور السيبانِيّ -

1 week agoالله!

عبد الغني المتوكل -

1 week agoوالله لم أعد أفهم شيء في هذه الحياة