Editor’s note: This translation has been edited and abridged from the original Arabic for style, clarity and concision.

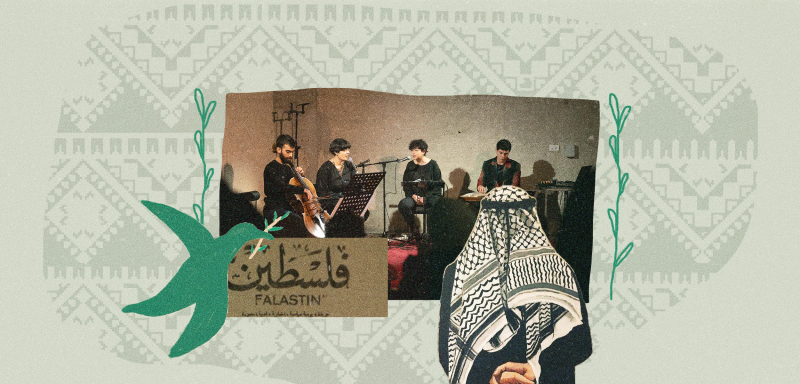

Dina Shilleh, founder of the Gradus musical project in Palestine, established the project in 2017 with the aim of supporting new musical creativity in Palestine.

“In Palestine, we mostly teach music from the classical perspective, be it Arabic or the Western classical,” said Shilleh. “When it comes to presenting new music there is a rejection on an institutional level of things that do not fall within the familiar. I needed to find a space to present my music. And I knew I was not the only one who needed this.”

Since its inception, the Gradus has provided a space for local composers and musicians to present their original works, document these productions, collaborate across diverse musical genres present in Palestine, and exchange knowledge to safeguard both traditional and contemporary music from fragmentation and discontinuity.

At its core, the project was designed to create a meeting space between musicians and audiences, sharing not only musical productions but also information and the creative process. This proximity is crucial for understanding how musicians interact with their music, their creative processes, their productions, and of course, the reality they experience under the ongoing Israeli occupation.

Our decision is to stay here

The beginning of the genocide in Gaza coincided with Gradus’ grant from the Arab Fund for Social and Economic Development in partnership with the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center. This overlap inevitably affected the project’s trajectory and programs, raising numerous questions and prompting research on the significance of music, the necessity of continued production, and the need to create spaces for listening, experimentation, knowledge-sharing, collaboration, and gathering amid catastrophe.

The theater became a home for musicians who had been deprived of platforms. Collective composition and joint performances turned into a form of resistance against cultural erasure, affirming that music is written for those who are here, as a child of place and memory.

“There are always constant interruptions to building something lasting,” said Shilleh. “The genocidal war posed questions about the value of life and the value of art.

“What does it mean to write, to sing? Music comes from the people who live here and experience everything. Music continues to speak about what we are living. She continues: “Therefore, the decision is to be here. We create here, we develop here, we nurture here. The only way to do that is with the people who are present here.”

Shilleh also sees music as central because it is a critical element of culture and resistance. Yet musicians face many challenges. One major issue is the lack of understanding of what music creation requires. There is a lot of discussion about music, musicology, ethnomusicology, and anthropology, but a deeper understanding of music — its components and how it is created — is missing, according to Shilleh.

A response to reality

Since the establishment of Gradus, Dina has worked alongside her husband Robin Burlton, a musician who has lived in Ramallah for ten years and works as a pedagogue and composer. Born in Scotland and raised in England, he shared his experience of his work titled “Yet Still I Sense You Everywhere,” from the second concert in the series “Expressions in Cultural Resistance.” Much of the music intersects with the lived reality of Palestinians at that historical moment, and Burlton sees it as “a direct response to reality.”

“In the performance, each of the six movements of the piece was preceded by a poem I had written in relation to a photograph. The audience was given time to read the poem and view the photograph before we commenced playing each movement,” Burlton told Raseef22. “The work was inspired by a journey we took in the summer, and by the idea of being able to travel and move between cities. I felt deeply aware of what travel means and the possibilities for movement, especially when coming from a place where restrictions are imposed on people’s mobility and choices.”

With the genocidal war on Gaza, the project turned into a question about the value of art amid the devastation. Here, music is no longer a luxury but a necessity, affirming that Palestinians continue to create despite all the ruptures.

Since inception, Gradus has involved approximately 80 musicians in composing and performing new music, as well as participating in lectures, workshops, and podcasts. Other participating artists come from diverse fields such as literature, graphic design, and photography.

Among the musicians is Maya al-Khalidi, whose involvement in Gradus coincided with her research on wailing songs, or tanawih in Palestinian dialect, and her creation of experimental music using texts from songs traditionally sung at funerals in Palestine.

Al-Khalidi began working on a project about Palestinian wailing before the Gaza war, and with its outbreak, the work became more connected to questions of grief, loss, and collective engagement through song and music.

“Through discussions with Dina about the project, the work took shape and evolved into ‘Wailing Songs of the Past: Might They Grow Our Resilience,’” al-Khalidi explained. “A question that always accompanied us, whether myself or many other musicians in Palestine and abroad, was: what should we do with music now? What is our appropriate role, and what is not? These questions motivated work in the present moment, which led me to develop the project further and collect additional songs until I reached five that formed a complete performance for the audience.”

Al-Khalidi process on this project offered her answers to questions of artistic purpose and meaning in times of genocide — answers that would not have been complete without audience feedback during the “Expressions in Cultural Resistance” series, joined in performance by Sarona, Faris Amin, and Zeina Amro.

“There were reactions indicating that we were in great need of sitting together to examine feelings of grief and anger,” al-Khalidi said. “I had thought wailing songs expressed only sadness, but many people felt and indicated that they also strongly convey anger. They noted that there are insufficient collective spaces to discuss these emotions that accompany us every moment of our day.”

Opportunity for experimentation in collective musical spaces

Faris Amin, a Palestinian cellist and teacher, was among the musicians involved in Gradus, having participated in its diverse programs himself.

On the added value the project provided him as a musician, Amin noted that the Palestinian musical scene before the war and before the COVID-19 pandemic offered limited performance opportunities. Most performances — then, and, to some extent, still — were confined to weddings, and restaurants, where audiences prefer familiar music, and many musicians rely on these performances for financial reasons or dedicate most of their time to teaching rather than composing or performing.”

Maya Khaldi’s experience with the tanawih redefined lamentation, not only as sorrow but also as anger and resilience. The songs became a collective space for expression, uniting people around shared emotions and offering them solace and the strength to face the moment.

Amin participated in composing and performing the piece “You Are Not in a Narrow Room,” which addressed the conditions of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli jails, alongside musicians Ibrahim Najm, Naseem Rimawi, Hossam Barham, Majdal Najm, and poet Dalia Taha.

“Gradus became a major opportunity to play with other musicians, and the group composition project was particularly special. It allowed musicians to perform, meet audiences, and appear on stage,” said Amin. “There are highly qualified musicians, but opportunities to perform are limited.”

The group worked on exploring possibilities for collective expression and producing art under harsh conditions as a form of resistance against cultural erasure. The performance was described as exploring “singing in the dark hour, recounting short monologues from prison history and from those who emerged through music, singing, and composition from its narrow cells.”

“The beauty of Gradus is that it opens a free space for creation, work, collaboration, and connection with other musicians and artists,” noted Amin. “Music is not only for the audience — it is created for music itself. This grants great creative freedom, within the general framework of Gradus. The freedom far surpasses many other contexts. This is what musicians need to continue.”

The end goal is longevity

The Gladus project has faced many challenges, primarily intersecting with the tragedy in Gaza and its ripple effects on Palestinians everywhere. What does it mean to write, to sing, to compose? Such questions often accompany every Palestinian engaged in art and creativity. The genocidal war pushed reflection not on the intrinsic value of art but on how to create meaning in context.

“Music continues to express what we’re living. I never doubted the value of art, but I had to struggle to begin,” said Shilleh. “Some assumed music could not express itself like other art forms, yet we continued creating, confident, to reflect our reality and our times.”

“There is no real separation between a musician’s experience and the life of a human being here. Everything is intertwined: emotion, personal experience, collective memory,” said Shilleh. “There is no small space to shield from the impact of heavy events on mental and physical health, and we do not attempt to escape. Music is a tool to process these burdens, both personally and collectively. Creativity is a way to understand and transcend reality, linked to collective memory and personal attachment to place.”

In Palestinian narratives, especially narratives of resistance to ongoing attempts at erasure by Israeli colonialism, art serves historically as a channel of resistance. Music, Dina observes, allows Palestinians to learn from the past and connect with previous generations, but most importantly, it enables thinking about the present and reshaping the future.

The future is full of both challenges and opportunities, including Israeli restrictions imposed on Palestinian artists and musicians, limiting their full freedom in production, composition, and performance. The greatest constraint is the ongoing political situation, increasingly harsh, alongside the lack of funding and institutional support.

“What is happening now is an effort to maintain the continuity of creativity, to prove that we exist and continue, and that Palestinian music is not merely nostalgia but something alive and evolving,” said Shilleh.

“The goal is our longevity, strengthening documentation, and affirming that Palestinian music is part of the global dialogue despite all difficulties. Through continuity, we can build a more resilient musical environment, educational and generative for future generations, proving that culture and art are integral to Palestinian society and identity.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!