This article comes as part of our commemoration of the 76th anniversary of the Nakba, a collection of personal and collective archives from Nakba survivors. This year, we shed light on archives that have been obscured by time or that have lived on in the hearts of their owners, their children, and their grandchildren. We shed light on them as we lose the original souls who lived through the Nakba. Much of these stories exist due to their passing onto the next generations, who continue to honor their family and ancestors by preserving and sharing their tales and experiences as if it were one continuous narrative.

Read in English here and in Arabic here.

This text was prepared in collaboration with the Palestinian Museum in BirZeit, Palestine.

Jaffa (Yafa), Ajami neighborhood, 1948; The Zionist war on the Palestinian existence escalates, so the Batshon family moves from their home in the Ajami neighborhood to the safer al-Nuzha neighborhood.

There, refugees from neighboring villages flock in droves, seeking refuge from the massacres committed by the Haganah. The family hears the horrifying news of the Deir Yassin massacre, conveyed by the peasant women who lived to tell the tale.

So, the father decides to save his daughters, and sends twelve-year-old Nuha and her sister to Amman, where their elder sister lives.

Nuha leaves Jaffa. And during her journey of asylum, exile and trauma, she partially loses her memory. It is almost as though she left parts of herself in the city.

"I was traveling from Rome to Sorrento, the weather and wind was coming from the east and it carried the scent of the Mediterranean, the port of Jaffa, and oranges. I opened the window and smelled the fragrance of orange blossom and lemon. And I don't know what happened to me. I started to sob uncontrollably, as if I was finally feeling all the horror that I went through at that time. When I smelled this scent, my memory came back to me."

Due to Nuha Batshon's ill health, we were unable to conduct a direct interview with her. But we recover and document her story here, through her personal archive and the testimonies of those around her.

Nuha regains her memory little by little, which turns out to be surprisingly accurate. She went on to live in Amman, produce art, collect artistic and heritage artworks, and document her life in a book.

Due to her ill health, we were unable to conduct a direct interview with her. But we recover and document her story here, through her personal archive and the testimonies of those around her.

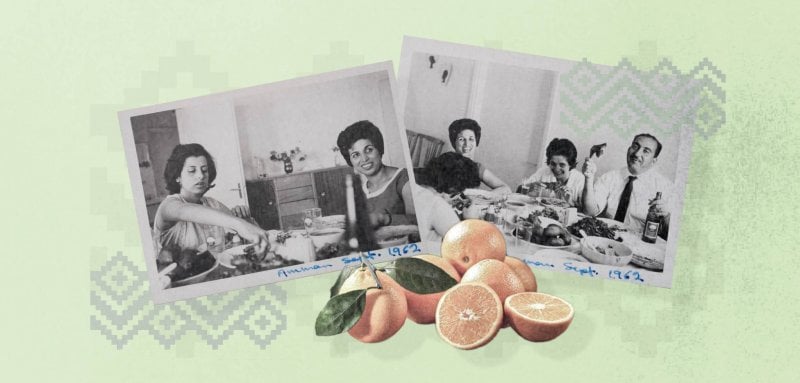

A photo of Palestinian artist Nuha Batshon, accompanied by her father and sisters while eating food at their home in Amman (Palestinian Museum Archive)

A photo of Palestinian artist Nuha Batshon, accompanied by her father and sisters while eating food at their home in Amman (Palestinian Museum Archive)

A memory evoked by scent

"In our orchard, we had a table set up outside. My dad used to buy oranges by the piece, in burlap bags. He would hang them off a donkey from both sides. He used to buy oranges and watermelons. We used to put the watermelon under the beds (our beds were high off the ground) to keep them cool. As for the oranges, we used to leave them outside. When we returned from school, we would squeeze them and drink their juice."

This is how Nuha Batshon remembered her home and the scent of oranges that lingered there, the act of imagination ingrained in her body.

"There was a long type of orange that we turned into little lights. We would cut off the top, empty them of their core, cut out little windows in them, and put candles inside to help us study," says Nuha in an interview conducted by Jinan al-Selwadi, a researcher in the field of arts.

"I was traveling from Rome to Sorrento, the weather and wind was coming from the east and it carried the scent of the Mediterranean, the port of Jaffa, and oranges. I opened the window and smelled the fragrance of orange blossom and lemon. And I don't know what happened to me. I started to sob uncontrollably, as if I was finally feeling all the horror that I went through at that time. When I smelled this scent, my memory came back to me."

"Nuha Batshon speaks in great detail about her relationship with Jaffa and the oranges in their home. She remembers everything in the house in precise detail, and she keeps all the family photos," al-Selwadi tells Raseef22, while discussing the process of documenting Batshon's story as part of the digital archive project at the Palestinian Museum.

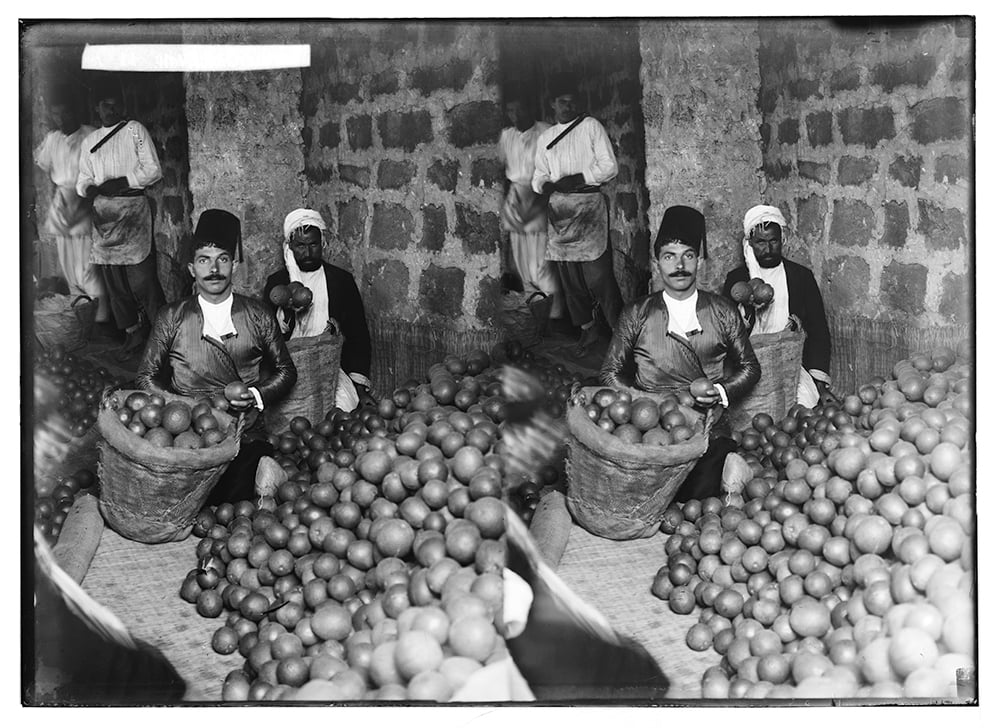

Despite her early years spent in Jaffa, the artist recalls the factory that was opened to manufacture the wrapping paper for oranges that Jaffa exports abroad, the details of the neighborhood, neighbors, and their cooperation in baking bread and cutting and drying okra, says al-Selwadi.

Packing Jaffa's oranges before they are exported

Packing Jaffa's oranges before they are exported

In contrast to this detailed narrative, Nuha was brief in her discussion of art. Perhaps this aligns with the fact that she only produced a few paintings during her artistic career and leaned more towards collecting art.

After the Nakba, the Batshon family managed to travel to their family home in Jaffa, which would have afforded Nuha the opportunity to re-see these memories in their original place. However, she opted not to go.

"When it became possible for us to travel and see our house in al-Ajami, I couldn't go. My older sisters and brother were able to travel and went to see the house. The neighbors told them that the house had been turned into a synagogue."

A nun without a monastery

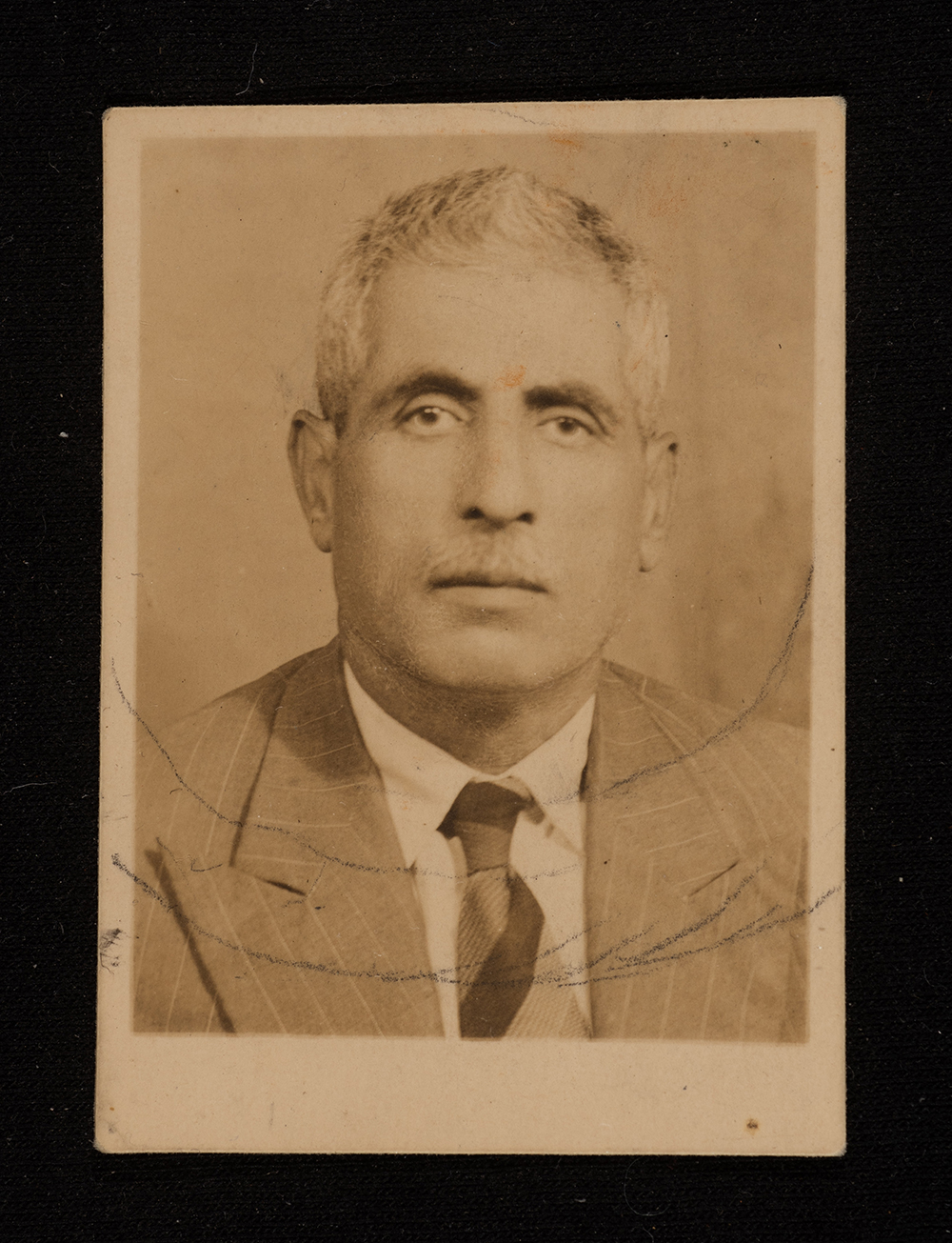

"I remember her talking about her father, who worked for the Falastin newspaper. Nuha mentioned that he mostly remained silent, and during exile, he planted a tree and wanted to take it back with him to Palestine when he returned," shares al-Selwadi.

Nuha's friends used to ask her about her memories of Jaffa. But she couldn't remember anything, even though she was displaced from the city at the age of 12.

Ibrahim Batshon, father of Nuha Batshon (Palestinian Museum Archive)

Ibrahim Batshon, father of Nuha Batshon (Palestinian Museum Archive)

When Nuha finally began to recall her memories during her journey from Rome to Sorrento, her feeling of pain deepend and she decided to write her memoirs and gather the pieces of herself and her life scattered by the Nakba. She began writing from the Ajami neighborhood in Jaffa in 1963 and ended up publishing the book "A Nun Without a Monastery."

Reclaiming memory appears to be an act of resistance against trauma and silence for Batshon. "Israel has constantly and continuously tried to turn Palestinians into a people without memory, starting from their theft of private libraries and government archives in 1948, then repeating the act in 1967, then in Beirut in 1982, and in Ramallah during the invasion. However, Palestinians have not stopped archiving their memory and history, as well as transforming their oral memory into written memory," artist Amer Shomali, director of the Palestinian Museum, tells Raseef22.

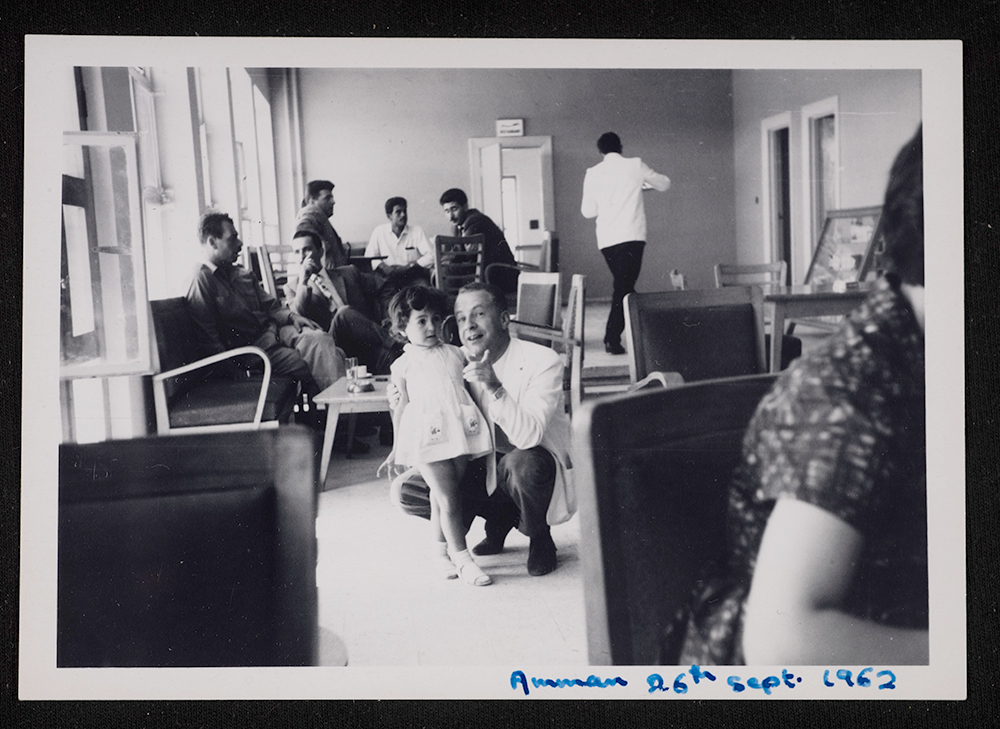

A photo of members of the Batshun family in Amman, taken on September 26, 1962 (Palestinian Museum Archive)

A photo of members of the Batshun family in Amman, taken on September 26, 1962 (Palestinian Museum Archive)

Sleeping class at school

Nuha Batshon studied journalism in Egypt and worked in media at the BBC channel. Then she moved to the Gulf to work and support her family before finally settling in Amman.

Poet Zulaikha Abu Risha tells Raseef22, "Nuha was one of the pioneering women in Jordanian media. I believe she was one of the most active and influential figures at that time."

She adds, "In the late sixties and early seventies, she worked as a presenter in the English section of Jordan TV, gaining very notable fame as a media personality."

There is no specific intellectual pattern that creates an individual's passion for art, but her childhood experiences and some seemingly ordinary details created a nucleus for Batshon's creative practice.

Yvonne Batshon, sister of Noha Batshon (Palestinian Museum Archive)

Yvonne Batshon, sister of Noha Batshon (Palestinian Museum Archive)

Nuha remembers "sleeping class" during her school days in Jaffa, sharing, "We used to lie down on the mats on the floor in a specific room and be quiet. Some girls used to sleep, but I used to daydream and stay silent. This taught me to sit alone and think a lot."

Abu Risha explains, "Nuha began collecting art in Jordan after a trip to England during which she visited international art exhibitions. She returned and opened the first gallery in Jordan, 'Gallery 14,' at the 'Jordan International Hotel'.”

The gallery was a small hall that housed a large number of paintings, drawings, sculptures, and pottery pieces by artists from Palestine and Jordan.

Abu Risha continues, "The importance and significance of this space was immense at that time. In the late seventies and early eighties, the Jordan Hotel was continuously hosting visitors, and many Arab and foreign conferences and seminars were held there. I visited her exhibition several times, and everyone passing through the hotel would visit that gallery."

Jacket from the Hebron region (Al-Khalil), Nuha Batshon Collection (Palestinian Museum Archive)

Jacket from the Hebron region (Al-Khalil), Nuha Batshon Collection (Palestinian Museum Archive)

University of Arts

The Palestinian Museum has a digital archive of The Nuha Batshon Collection, which includes photos of her family members during their forced displacement. Today, an exhibition of artworks collected by the artist throughout her life is being opened.

Batshon produced few artworks, mainly paintings of landscapes and houses. She had her own philosophy in collecting art, choosing diverse pieces regardless of the artist's fame or name.

In an interview with Al-Ra'i Jordanian newspaper in 2020, she said, "I chose paintings by artists who studied arts in public schools but didn't receive recognition. Some works I chose for their Palestinian features in terms of concept and execution, as if the artwork carries a Palestinian political concept. I also chose others because they document the history of Palestinian clothing and jewelry."

Artwork by artist Mahmoud Sadiq, Nuha Batshon Collection (Palestinian Museum Archive)

Artwork by artist Mahmoud Sadiq, Nuha Batshon Collection (Palestinian Museum Archive)

Within Batshon's collection, we find glass pieces bearing abstract drawings of women, traditional pottery engraved with Arabic words, and artistic paintings dating back to the sixties. Additionally, the collection includes over one hundred and fifty traditional Palestinian dresses and garments, in a genuine attempt by Batshon to create a Palestinian aesthetic space in the world's memory.

In her collection of artistic works, which include glass pieces bearing abstract drawings of women, traditional pottery engraved with Arabic words, artistic paintings dating back to the sixties, and traditional Palestinian dresses and garments, Batshon tries to preserve her memory so as not to lose it again.

"In her collection of artistic works, Batshon tries to preserve her memory so as not to lose it again," says Amer Shomali, adding, "It seems that at the moment she felt that she was getting older, and so she donated these works she had collected to the Palestinian Museum out of fear that they would scatter and disappear again, and to serve as a beacon for future generations.

Shomali emphasizes, "Here, the Palestinian keenness on transferring memory and passing down history from generation to generation is evident. That same generation that the Israelis said would forget after its elders die."

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!