“Sir Albert, my boss sends his regards and wanted to ask your opinion on the shares of the textile factory.”

“Is he looking to sell or buy?”

“To buy.”

“Which textile factory, the one here or in Aleppo?”

“I don't know, really.”

“Go back to him and ask. him They are two very different companies.”

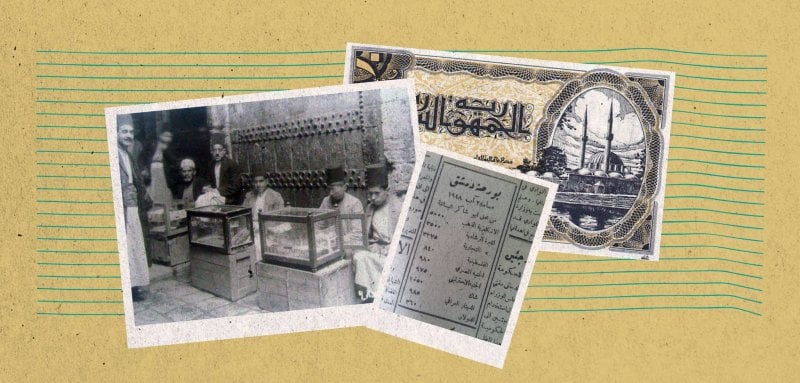

This is a conversation that took place daily in front of Albert's shop in the Bourse Souq in 1950s Damascus. The Bourse Souq was the commercial nerve center of Damascus, where traders, money changers, bankers, and brokers gathered daily. Some, like the bankers, came dressed in their foreign suits and ties, while most traders wore traditional cylindrical hats and short coats (Sako).

The Bourse Souq, the commercial nerve center of Damascus, was unlike other souks in other major cities, in terms of its size or transactions. It was lined with foreign currency dealers and shops trading stocks in major Syrian companies

The Bourse Souq opened in 1920, the same year as the Beirut Stock Exchange, in an old alley across from the famous Bouza bakery in the al-Hamidiyah Souq. The market was unlike those in other major cities, in terms of its size or transactions. It was lined with small currency exchanges and shops buying and selling stocks in major Syrian companies and factories. At the front of each shop, a salesperson behind a wooden table manned a glass box containing foreign currencies and a price list for Syrian companies.

The largest companies in the Bourse Souq

At the time, the two largest and most famous companies at the Damascus Bourse were the Cement Factory, known as Shmento, founded by Khaled Al-Azm in 1932, and the Conserves Company launched by Shukri Al-Quwatli in 1934, 9 years before he became President of the Republic. The stock price of these companies remained stable and underpinned by the respect their founders and board members enjoyed, they were considered the most secure investments in the Bourse Souq.

Traders in the Bourse Souq in Damascus

Traders in the Bourse Souq in Damascus

The Cement Factory capital was set at 144,000 Ottoman Gold Liras, and its shares were distributed among 24,000 shareholders. Investors purchased a piece of land in the Dumar area, northwest of Damascus for their project. By 1939, before the outbreak of World War II, the factory's production reached 65,000 tons of cement.

“Some studied economics at Harvard Business School, but you must attend the al-Hamidiyah Souq Business School: the best teacher in trade and ethics.”

Before it was nationalized in 1965, the number of employees at the Conserves Company reached 200, and it produced and exported 25,000 tons of canned goods to Egypt, Palestine, Iraq, and the Hejaz.

Al-Quwatli refused to sell the company's shares through foreign banks and insisted that public offerings be conducted either through the Damascus branch of the Bank of Egypt or through the Arab Bank. He often gifted company shares to his friends on the occasion of their marriage or the birth of a child.

The young Lebanese Nadim Dimashqiah managed the Conserve Company in its early days. The American University in Beirut graduate would later become the Lebanese ambassador to the United States during John F. Kennedy's presidency.

Shares of the Conserve Company were traded on the Bourse Souq, and a man by the name of Anwar al-Zalak monopolized the sale, competing with Abu Moufaq al-Tasabehji, who dominated the trading of shares of the Cement Factory. Both companies’ reputation spread within commercial circles. The first religious judge in Damascus even gave people the choice between distributing their inheritance in cash, or placing their money in one of these two companies. Shares of the Spinning and Weaving Factory, the Glass Factory, the Sugar Factory, and the famous Khumasiya, established in 1946, were also traded on the Bourse Souq.

Al-Hamidiyah Souq (Business School)

At the time in Syria, there were no universities specializing in economics and finance, nor were there any books to refer to in the study of the Syrian economy. The only exception was a book written by the poet and lawyer Rafiq Salloum titled The Life of the Country in the Science of Economics. It was published in Homs in 1912 and discussed trade, industry, taxes, workers' rights, and the duties of factory owners. Four years after the book's publication, Rafiq Salloum was executed with his nationalist comrades in Marjeh Square in Damascus on May 6, 1916.

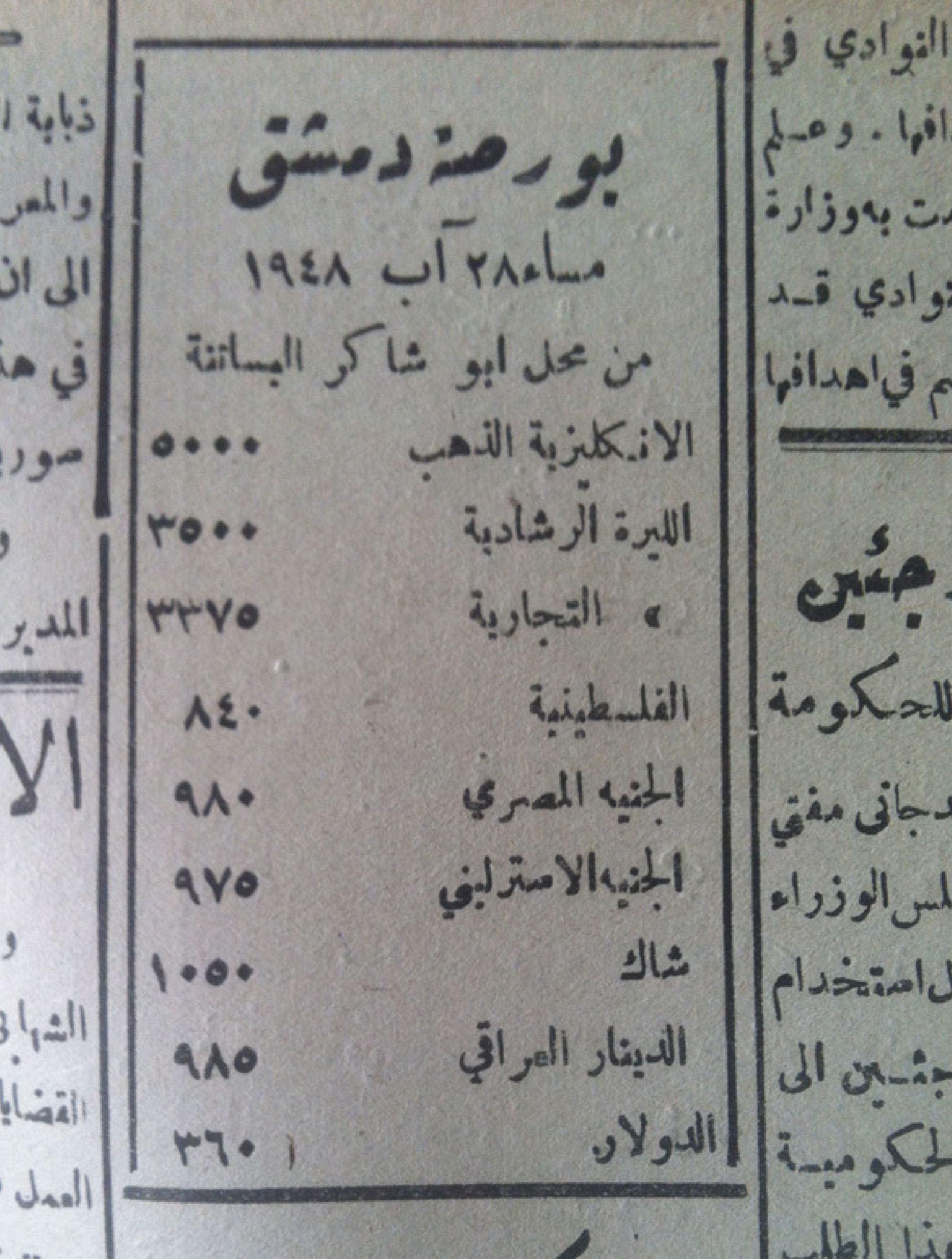

Currency rates in the Bourse Souq in Damascus

Currency rates in the Bourse Souq in Damascus

It was only in 1958 that Syria’s first college of commerce and banking opened. It was founded by the director of the Damascus Chamber of Commerce, Abdul Ghani Hammour, in collaboration with the president of the Syrian University, Dr. Ahmed Samman, father of the author Ghada Samman. Hammour envisioned it as an exemplary college, with no more than twenty-five exceptional students studying English in the first year. Students learned the principles of business by monitoring the old markets and souks, visiting banks, the Bourse Souq, and the al-Hamidiyah Souq.

Hammour would affectionately tell his students, “Some studied economics at Harvard Business School, but you must attend the al-Hamidiyah Souq Business School: the best institution to learn trade and ethics.” During Syria’s union with Egypt, President Gamal Abdel Nasser opened the doors of the college to accommodate the largest possible number of students, in line with his socialist policies. Classrooms went from teaching 25 students to 500, encompassing both “the righteous and the mischievous.”

After the Bourse Souq was nationalized between 1961 and 1965, all major companies withdrew from it and then-President Amin al-Hafez prohibited trading. Today, the once-grand souk is a darkened alleyway, where jalabiyas and women's clothing are sold.

A unique incident

Stock investment culture was cemented in the first half of the 20th century, after several banks faced bankruptcy following the Great Depression of 1929. Merchants in the Levant were concerned about putting their money in banks, especially given the atmosphere of instability at the start of World War II. One such bank was the Bank Murakada, founded in 1930 by the prominent Michel Murakada in the Al-Buzuriyah Souq.

Bank Murakada served as a trusted institution for political figures, but experienced severe financial shock after a member of the Murakada family went bankrupt. This family member, who worked as a money changer in the Bourse Souq, caused a rumor to spread through the markets that the bank had gone bankrupt.

A scene from the Bourse Souq in Damascus

A scene from the Bourse Souq in Damascus

People rushed to withdraw their deposits at an astonishing speed that exceeded the bank's capacity to provide the required liquidity. The bank began scheduling the repayment of deposits, and when the depositors' agitation increased, management decided to compensate them with properties in Damascus and other Syrian cities. The Bank Murakada went bankrupt and closed its doors forever, its elegant former headquarters, now a store selling spices and sweets, remains a testament of a bygone era.

The fate of the Bourse Souq was not much better. After it was nationalized between 1961 and 1965, all major companies withdrew from it and then-President Amin al-Hafez prohibited trading. Today, the souk is a darkened alleyway, where jalabiyas and women's clothing are sold.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!