Journalists, government officials, and media watchdogs have struggled to agree on standards, regulations, and punishments as Lebanon attempts to reform its media environment.

Laham’s unlawful detainment represents but one of many high-profile cases of prominent Lebanese activists and journalists facing investigation for statements made online or in media. A month earlier, a judge issued a decision ordering journalist Dima Sadek to pay various fines and serve one year of imprisonment for a tweet posted in 2020 comparing Lebanon’s Free Patriotic Movement party to the German Nazi Party. In May, a judge summoned prominent journalist and feminist activist Hayat Mirshad before a criminal court in Beirut due to a defamation complaint filed by film director Joe Kodeih. On March 30, two State Security officers illegally intercepted Megaphone cofounder Jean Kassir on the orders of Lebanon’s General Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat allegedly in part due to a previous Megaphone piece calling Lebanese officials “fugitives” for their role in the Beirut port blast. Just a day later, Lebanon’s Cybercrimes Bureau summoned Lara Bitar, the editor-in-chief of Public Source, due to a complaint filed by the political party Lebanese Forces related to Bitar’s investigative journalism.

Credits: Alternative Syndicate of Press

All of these cases of blatant freedom of speech and press violations are indicative of a larger trend emerging across the country—that of major judicial and political figures exploiting criminal defamation laws and a shaky legal framework to stifle criticism and attack opponents. The Lebanese government’s increasing investigations into online activities are marked by their general ambiguity. They also take advantage of the lack of legal protections for journalists and digital actors in Lebanon. Ramzi Kaiss, a Human Rights Watch Lebanon researcher, thinks this signifies a growing pattern of censorship. “Th[e] practice, or pattern, is to go after everyone criticizing the work of the government,” he said. Politicians and the judiciary, increasingly emboldened by a system characterized by a lack of accountability, are perpetrating widespread crackdowns on online journalists.

Raseef22 analyzes online freedom of expression for Lebanese journalists and breaks down the legal steps towards a new media law. Raseef22 spoke with NGOs to understand the legal implications currently posed by a draft media law.

In this article, Raseef22 analyzes online freedom of expression for Lebanese journalists and breaks down the legal steps towards a new media law. Raseef22 spoke with several nongovernmental organizations to better understand the efforts being put in place to protect journalists and the legal implications currently posed by a draft media law aiming to improve the status quo that has been in development since 2010.

The Current Legal Framework: A System Simplifying the Demonization of Online Media

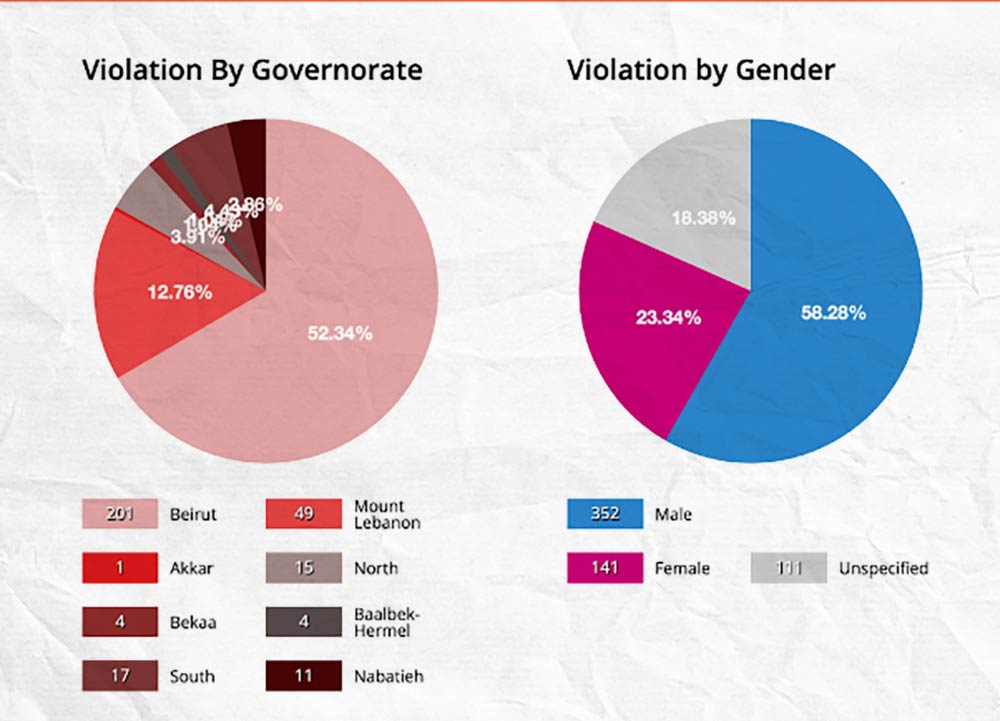

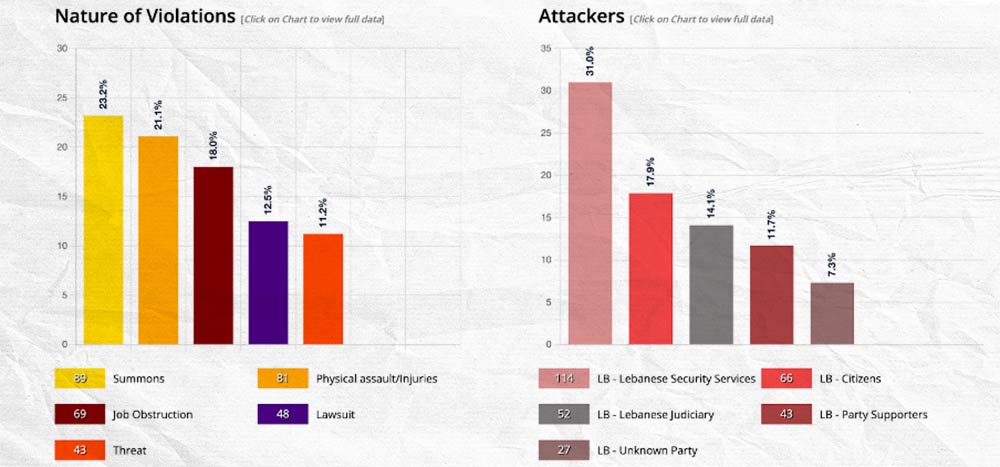

The Lebanese government’s targeting of journalists and online freedom of expression has intensified since the October 17, 2019, uprising. There have been 384 documented general freedom of expression violations in Lebanon since December 2019—a human rights violation occurring nearly every four days. These recent crackdowns, benefiting from loopholes and ambiguity in Lebanon’s penal code, often target online journalists.

Credits: Samir Kassir Foundation

Credits: Samir Kassir Foundation

“All of the laws applying to journalists, and their opinions, are scattered and do not mention anything connected to online [journalism],” says Layal Bahnam, Program Manager at the Maharat Foundation. Bahnam emphasized that the current body of laws governing journalists, the Publications Law, is highly outdated, with much of the law’s articles having been adopted in the 1960s, 70s, 80s, and 90s. Lebanese media are specifically governed by the 1962 Press Law and the 1994 Audiovisual Media Law. Because most of these laws were drafted before the advent of the internet, they necessarily fail to mention online journalists and how publication laws may apply to them.

The Lebanese government’s targeting of journalists and freedom of expression has intensified since the 2019 uprising. There have been 384 documented general freedom of expression violations since - a human rights violation occurring every four days.

Moreover, due to the law’s wording, journalists only receive protections from the law if they are members of Lebanon’s Editors Syndicate. Many journalists today, however, are not. “Freelance journalists, YouTube channel creators, and [journalists] on social media are all dismissed by the current media law," says Farouk al-Moghraby, lawyer of the Alternative Syndicate of the Press. The Court of Publications, a criminal court that oversees crimes involving journalists and media professionals, further muddies the legal definition of a journalist.

Although Lebanon’s current media law fails to mention websites and online journalism, the Court of Publications includes websites under its jurisdiction. This ambiguity has led some judges to argue that websites are not protected by the Publications Law. To al-Moghrabi, this is precisely where violations can take place. Lebanon’s Public Prosecution seems to be violating the Court of Publications’ jurisdiction, claiming that websites do not fall under its authority. This infamously impacted Hayat Mirshad, as the Public Prosecution claimed her media platform’s website did not fall under the Court of Publications’ jurisdiction. Because of this, the current media law could pose legal ramifications on both social media users and website publishers.

Lebanon’s only law that clearly discusses online activity, the Electronic Transactions and Protection of Personal Data law issued on October 10, 2018, allows Lebanese authorities to indefinitely block websites and stop electronic services. Bahnam pointed out that the law is not up to international standards and restricts the free flow of information on the web. And because the laws mentioning journalists are ambiguous and outdated, they open the door for loopholes and exploitation. Online journalists, confronted by no reliable legal framework to support them and the evolved medium of their profession, consequently face a constant threat of legal retribution.

Many calls for investigations rely on the criminalization of defamation and insults based on criminal “slander and libel” laws. In several reports, Human Rights Watch has found that powerful Lebanese political and religious figures have increasingly used the country’s criminal insult and defamation laws against opponents accusing authorities of corruption and reporting on the country’s worsening economic and political crises. This allows them to circumvent needing civil courts, pursuing more serious legal ramifications against those investigating or even discussing their work.

“This pattern is rather political and goes beyond the legal aspect,” stressed Ayman Mhanna, executive director of the Samir Kassir Foundation. Mhanna added: “We’ve seen cycles of attacks on freedom of expression. We saw the same wave happening 10 years ago, for instance […] in 2016 when political leaders had one common enemy: independent journalists.” And since 2019, the Samir Kassir Foundation has tracked the same pattern of violations forming again. “In Lebanon,” Mhanna emphasized, “repression often reflects the political wind.” These violations tend to increase when social and political tensions are high. And with laws being outdated, this directly paves the way for authorities to leverage legal gaps against political opponents.

Human Rights Watch has found that powerful Lebanese political and religious figures increasingly use the defamation laws against opponents accusing authorities of corruption and reporting on the country’s worsening economic and political crises.

To rectify this legal ambiguity, a new draft media law has been in the making since 2010. However, despite multiple revisions over the past decade, the draft law still fails to protect online journalists and several aspects of freedom of expression.

Deconstructing Lebanon’s Draft Media Law and Online Freedom of Expression

Lebanon’s draft media law began forming in 2010 when the Maharat Foundation began working alongside media professionals and international experts to draft its own version of an updated media law. Critically, the Maharat Foundation’s draft law included an essential component guaranteeing freedom of expression.

However, as Maharat Foundation pointed out to Raseef22, the draft began to become distorted over time, particularly after two Parliamentary committees — the Information and Communication Committee and the Justice and Administration Committee — amended the draft law. Member of Parliament Ghassan Mokhaiber submitted the original version of the draft media law for parliamentary review in 2010, and the Committee of Information and Communication finished discussing the draft law in 2016. The law was then referred to the Justice and Administration committee, where it has remained to this day as it awaits transfer to the Parliament’s general assembly for a vote. Moreover, because deliberation of and updates to the law have taken over a decade, many parts of the Maharat Foundation’s recommendations have either become obsolete or are again in need of an update. According to The Alternative Press Syndicate’s al-Moghrabi, both edits in the Parliament disrupted and modified the freedom of expression component in the draft law. Al-Moghrabi, who worked closely on the drafts, noted that neither edit abolished a pathway for imprisoning journalists. The first edit even added a possible prison sentence for journalists not present in the initial 2010 draft.

In 2022, UNESCO officially began working on reforming Lebanon’s media law, and in May 2023 publicized its suggested amendments. Likewise, in 2022 the Alternative Press Syndicate offered comments on both the latest media law draft and UNESCO’s comments to ensure greater press freedoms.

The Alternative Syndicate’s latest suggestions to UNESCO’s draft recommend excluding online media platforms from restrictions, instead attempting to restrict licensure and fines solely to specific radio-broadcast organizations. Furthermore, the Alternative Syndicate recommended replacing regulatory media committees with online media self-regulation, ensuring safeguards for online journalists caught up in criminal investigations, and redefining the term “journalist” to fall more in line with digital media standards approved by the UN and international community. One of the most important changes the Alternative Syndicate is fighting for is to abolish the Court of Publications. With the backing of the Maharat Foundation, the Alternative Syndicate is now internally discussing its comments with various members of Parliament while it also actively works alongside other civil society organizations and media activists.

Al-Moghrabi also stressed the importance of removing any remnants of the outdated media law still in the draft law, as they barely relate to modern journalism. However, the current draft law in all its versions still lacked a clear mechanism for handling “online journalism.” This is where the Alternative Syndicate’s efforts to protect online journalists through the law have become increasingly necessary.

Ratifying Outdated Laws or Securing Greater Press Freedoms?

The draft law continues to pose potential harm unless those in power begin prioritizing basic liberties and human rights. Bahnam and al-Moghrabi both highlighted that many activists now consider it better to have no law at all than to have an amended one, as authorities could leverage the new law to further regulate journalists’ freedom of expression. To Mhanna and the Samir Kassir Foundation, the primary issue at play revolves around the political system’s fundamental lack of belief in basic human rights. Even if the draft media law was perfect, Mhanna argued that it still would not fix the situation due to Lebanese society’s lack of trust in the government and Lebanese authorities’ disrespect for fundamental freedoms.

Credits: Alternative Syndicate of Press

To help mainstream the acceptance of international standards of human rights law, the Maharat Foundation also aims to influence lawyers, judges, and academics to engage with policymakers. “The issue for us is not lobbying for the law... [it is] informing the debate, benchmarking with international and European standards, and taking what applies to Lebanon. We are trying to leverage on freedoms rather than journalism, especially in the online sphere to ensure protection for all,” Bahnam stressed.

Bahnam, Mhanna, and al-Moghrabi are not proposing a free-for-all media environment. All three agreed that regulation of hate speech was vital but suggested that taking cases of users to civil courts rather than penal courts is essential. “Jail and freedom of expression are not proportional, and drawing the line between hate speech and freedom of expression is essential […] but defamation should not be confused with hate speech and any reform of [the] laws should not unduly limit the right to freedom of expression,” Bahnam emphasized.

Amid ongoing political attacks on free speech, though, the Samir Kassir Foundation is prioritizing tracking and monitoring Lebanese political dynamics. According to Mhanna, “While there have been a lot of violations attacking these [media] platforms, it has not necessarily affected the way these media work. The repression comes from the public narrative that [political actors] are trying to build in order to demonize, rather than [from the] legislation alone.” Mhanna cautioned that traditional political parties have gotten away with murder, blackmailing the international community, and consolidating their presence through political scapegoating of vulnerable and marginalized communities. With a narrative building that demonizes journalists, government actors and their allies are scapegoating civil society actors, posing major implications for the 2026 general election.

Whether through political resistance or civil society strengthening, prioritizing freedom of expression is crucial to not only safeguarding journalists but also ensuring that everyday Lebanese people are protected from being silenced. The draft media law in review threatens those freedoms, opening the door to the criminalization of online freedom of expression. Unless the draft law changes, Lebanon could head toward a more restricted media environment and an even greater level of impunity for government officials.

“The grand issue in Lebanon,” Kaiss warned, “is that there is no accountability. Those in power enjoy a level of impunity that prevents justice from being carried out.”

*This report has been prepared within the project "Media Reform to Enhance Freedom of Expression in Lebanon."

The European Union funded this publication. The responsibility for its content lies solely on Maharat Foundation and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

*This article was proofread and edited by Jesse Kireyev.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!