Farmer Ali Issa sprays the weeds that have started to grow among the crops in his farm. He has zero tolerance for this agricultural hazard that impacts the quality of the produce and attracts harmful insects and diseases to his crop. The pesticide he uses is very efficient and the results can be seen within just two days of application, even though it is banned internationally, and has been banned in Lebanon for ten years.

Issa, a 50-year-old man from the Ras al-Ain area in the city of Tyre, insists on using "paraquat", a pesticide that has been linked to Parkinson’s disease and has been banned by some countries like Sweden since 1983. He uses it out of habit and past experience, as well as due to its proven efficacy over the span of many years. He would not try other pesticides as that could risk him losing an entire season's harvest.

Paraquat, along with other similar types of pesticides, has been banned from entering Lebanon, but they're still widely used despite their health and environmental risks.

Collected in Lebanon.. 76% of the samples contaminated

We may be tempted by descriptions such as “red and juicy tomatoes” and “fresh green cucumbers” in catchy phrases used by vendors, but appearances can be deceiving and sometimes deadly. To verify this hypothesis, we tested some samples of the vegetables in laboratories. Whatever the naked eye cannot see can be exposed by a microscope.

Destination: Agricultural lands in the seven Lebanese governorates of Baalbek-Hermel, Beqaa, North Lebanon, Akkar, Mount Lebanon, South Lebanon, and Nabatieh.

Mission: To collect samples of tomatoes and cucumbers to examine pesticide residues in them. These two vegetables were chosen because they constitute 50% of the areas cultivated with vegetables in Lebanon.

Time of year: Summer 2021

The samples were collected from agricultural lands to ensure that the vegetables we collected were produced in Lebanon, and were not imported or intended for export. This means that they are consumed by people residing within Lebanon. We also made sure that the fruits were ripe and ready for harvest, and not in the period right after spraying (pesticide application). We also refrained from collecting any crops that the farmer told us had just been sprayed and that he was waiting a few days before he could pick them.

We traveled north first, to the coastal governorates of Akkar, then to Mount Lebanon and South Lebanon. The tomato and cucumber season begins in early spring when humidity is high, and temperatures start to rise. This time of year, the weather is perfect for these two crops, though not so much for us, as our car did not have air conditioning.

In coastal areas, protected cultivation patterns inside greenhouses are the most common method used, as these plastic covered constructions retain heat and raise humidity, especially in winter. But in the inner governorates of Baalbek, Hermel, and Beqaa, field cultivation and farming is more dominant, and so the harvest season there is delayed until the beginning of summer.

The total number of samples examined in RBML laboratories, which are accredited by the Lebanese Ministry of Agriculture, were 46 samples, 25 of which were tomatoes (indicated below in red) and 21 cucumbers (indicated below in green).

The tests revealed that 76% of the samples were contaminated by pesticides, and only 11 samples out of 46 (or 24%) did not contain any residues.

Comparing the results with the latest list of banned pesticides issued by the Ministry of Agriculture in April 2021, revealed that more than half the samples contain residues of pesticides banned in the Lebanese market, some of which have been banned years ago. A fifth of the samples were found to contain high levels of pesticides that exceed the maximum permissible residue limit set by the Lebanese Standards Institution - LIBNOR.

In one of the samples, the residues from the banned pesticides exceeded the maximum limit by 18 times, and were four times higher than the limit of a non-prohibited pesticide in another sample. Even though it is not banned, it is classified by the World Health Organization as very hazardous, as it is suspected of affecting fertility and leads to deformities and malformations in fetuses.

The number of compounds detected in the samples reached 20 compounds, and they include active substances and 9 banned compounds. This means that farmers have been using both banned and approved pesticides in equal measures, and this is reflected in the spread and availability of these types of pesticides in the market, despite their high costs.

The sources of pesticides

A questionnaire prepared and conducted by the investigator including 53 farmers from different Lebanese regions, showed that 89% of farmers obtain pesticides from agricultural pharmacies. 47 of them stated that they use pesticides regularly, while only six farmers stressed that they do not use any kind of pesticide.

We traveled north first, to the coastal governorates of Akkar, then to Mount Lebanon and South Lebanon. This time of year, the weather is perfect for the crops we were investigating, though not so much for us, as our car did not have air conditioning

Only 12% of farmers buy pesticides from street vendors, smugglers, or unlicensed stores. In Lebanon, licensed pharmacies operating under the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture are the main source of the “pesticides chaos” in the country.

The testimonies of the farmers we interviewed during our field tours reveal that they obtain banned pesticides from agricultural pharmacies (phyto-pharmacies), whose owners purposely avoid displaying them openly on the shelves and keep them hidden in warehouses away from scrutiny.

Farmers exposed to toxins

Just like 75% of Syrian refugee children residing in the Beqaa Valley, 16-year-old Wissam has been working in agriculture since the tender age of twelve despite the risks these children are exposed to, including their exposure to pesticides.

Wissam spends many hours in the fields, weeding, harvesting potatoes, growing cucumbers and tobacco. Spraying pesticides is not one of her tasks, but this does not make her immune to their hazards. The supervisor – the group leader in the camp or farm — does not usually allow the workers to leave the field when the pesticide spraying begins, nor does he provide them with protective equipment such as masks, gloves, or shoes. Wissam simply wraps a handkerchief around her face, to cover her nose and mouth, but the pungent smell of the pesticides still penetrates through and has repeatedly given her symptoms such as shortness of breath, dizziness, red eyes, nausea, and vomiting. These symptoms of poisoning only go away when an IV serum is provided at the clinic.

We may be tempted by catchy phrases used by vendors like “red, juicy tomatoes” and “fresh green cucumbers”, but appearances can be deceiving, and sometimes deadly. To verify this hypothesis, we tested some samples of the vegetables in laboratories

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that three million cases of acute pesticide poisoning are registered annually on a global scale, resulting in 40,000 deaths. In Lebanon, there are no statistics on cases of pesticide poisoning, but according to the questionnaire, one out of every five farmers has been poisoned at least once as a result of negligence when it comes to preventive measures, since the same exact percentage of farmers do not believe that pesticides pose a threat to health.

The results of the tested samples have shown that one compound out of nine is banned and is highly toxic, according to the World Health Organization. But what is remarkable is that two of the non-prohibited compounds are classified as “severe and high risk”. This raises questions about the Ministry of Agriculture’s decision to allow the import of highly toxic compounds without considering their health and environmental damages. But the ministry defends its decision claiming that they are still in use in "reference countries" (countries that Lebanon refers to when it comes to banning or allowing a pesticide), namely: the European Union, the United States, Switzerland, Canada, and Japan.

"The dose makes the poison"

Pesticide expert Doctor Salem Hayar notes that, “All the used compounds that appeared in the tested samples are traditional pesticides that have been used for a long time and are now discontinued. I used to regularly advise the Ministry of Agriculture to abandon them and to introduce new pesticides because insects or pests have acquired immunity against them.”

He explains that, as a result, "It has become necessary for farmers to increase the concentration and dose of the pesticides to increase their effectiveness while also often using the same pesticides on a multitude of crops, including tomatoes, cucumbers, and others.”

The danger of these practices, he continues, lies in the fact that they “raise the consumed dose of a specific chemical compound, which leads to the accumulation of toxins in the body, whereas it would be better to use selective pesticides that act on a particular insect or pest. Therefore the doses would be distributed over more than one pesticide, thus reducing the amount of the consumed dose and does not exceed its normal proportions, and that is when it can be consumed over a lifetime without being exposed to a tangible risk to health."

When the pesticide spraying begins, little Wissam wraps a cloth around her face to cover her nose and mouth, but the strong smell of the pesticides still penetrates through and gives her symptoms like shortness of breath, dizziness, nausea and vomiting

Hayar stresses that pesticides turn into poison if they exceed the permissible levels, just like medicines for humans. He cites the father of toxicology Paracelsus who once said: “The dose makes the poison”.

The health effects of pesticides extend beyond those that appear immediately after exposure through the skin, mouth, eyes, or inhalation and cause poisoning, dizziness, and nausea. More serious long-term effects can also occur, including cancer, neurological disorders, and reproductive health problems, like miscarriages, fetal deformities, and weak fertility, as well as chronic respiratory diseases like asthma. These are all scientifically proven facts and are not up for debate, but it all depends on the amount of pesticide and the duration of exposure.

"Pesticide mafias"

Dr. Nada Nehme, vice president of “Consumers Lebanon”, an organization that defends consumer rights, says, “Food and environmental pollution is a major cause of the increase in cancer cases in the country.”

The World Health Organization’s International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) stated that in 2020, Lebanon ranked third in the number of cancer cases relative to the size of its population in the Eastern Mediterranean region.

In 2003, “Consumers Lebanon” launched a campaign to reduce the use of pesticides in cooperation with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Ministry of Agriculture, but after 18 years, “There is no progress," Nehme regretfully says, "because the Lebanese government has not done anything so far. All the recommendations we listed in our meetings with the Ministry of Agriculture or with the Parliamentary Agriculture Committee failed.” The entities that obstructed solutions are the “pesticide mafias'' as Nehme describes them, or “the merchants and people from the legislative and executive authorities who help them.”

The state at the service of merchants

Towards the end of 2017, the former Minister of Agriculture Ghazi Zuaiter issued a decision to allow the re-importing of 18 out of 36 pesticides that the former Minister of Agriculture Akram Chehayeb and Minister of Health Wael Abou-Faour had banned under decision No. (1048/1), issued on June 13, 2016. The first item of the resolution explained that the pesticides “are linked to cancer and pose a danger to pregnant women.”

Zuaiter justifies his decision by explaining that these pesticides “are still registered and used in several (so-called) reference countries. There are no alternative pesticides to some when it comes to fighting some weeds or insects, which has caused a problem for farmers, increased the cost of production, and may be a reason why some resort to smuggling.”

“The dose makes the poison”... Pesticides turn into poison if they exceed the permissible levels, just like medicines for humans

Nehme does not find Zuaiter's justification convincing. She believes that what happened raises questions about the justification for bringing these substances back into Lebanon after they had been banned for more than a year, a time period during which farmers were able to manage without them. She adds, “Even if they're banned in only one country, that's enough reason for us to stop using them.”

Questions also arise about the validity of the decision taken by the two government ministers Chehayeb and Abou-Faour, which gave a one-year grace period for the use of "carcinogenic" pesticides included in Resolution 1048. Fourteen days later, they issued a joint decision that falls under No. (1202/1) to exclude a shipment of pesticides that had already arrived at the port of Beirut from the ban, as they were already in transit when the decision had taken effect. According to what was stated in the first clause, they were “shipped before the date of its issuance according to the documents submitted by the concerned parties,” which means that the two ministers who issued decision No. 1048 were the first to violate it, and the goods were allowed in instead of being shipped back to its country of origin.

The story does not end here. In 2016, the Association of Importers and Traders of Agricultural Production Supplies in Lebanon filed an appeal to invalidate these two decisions before the State Shura Council (the supreme court that handles the administrative judiciary). The association claimed that “the harm and danger of the agricultural pesticides subject to the two decisions have not been proven”. The association’s presidency said in a statement that it “objected to the fact that the Agricultural Medicines Committee was not consulted, as it is the entity concerned for making decisions regarding the trade of agricultural plant medicines.”

To verify the association’s claim, we cross checked them with those of the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) list of carcinogens. It became clear that 32 out of the 35 compounds covered by the decision (with one compound not included in the list), were classified as likely to or may cause cancer. According to the US Department of Health’s open database on chemicals, 11 compounds cause fertility problems and harm fetuses. Despite this, on March 8, 2018, the Lebanese Shura Council repealed the decisions of the Ministers of Agriculture and Public Health on the pretext of “overstepping the association’s authority and violating the core principles stipulated in laws and regulations.”

The inconsistencies in the decisions did not end there. At the beginning of 2018, the implementation of Zuaiter’s decision was suspended until an independent scientific committee of experts could complete a thorough study and evaluation of the active ingredients. To date, such a committee has not been formed.

Only 12% of farmers buy pesticides from street vendors, smugglers, or unlicensed stores. In Lebanon, licensed pharmacies operating under the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture are the main source of the “pesticides chaos” in the country

“Legal” smuggling

The governorates of Akkar and Baalbek-Hermel accounted for the highest percentages of samples that contain banned compounds at 29% and 25%, respectively. They are also the two governorates that share a large border area with Syria, with 5 official crossing points, and 124 illegal crossings used mainly for smuggling fuel, goods, contraband, drugs, and pesticides.

The smuggling of agricultural pesticides is not limited to illegal crossings. Data collected from news and newspapers since 2010 points to the massive volume of seized goods at legitimate crossings, including the port of Beirut, with many shipments making it into the country. On July 19, 2019, former Minister of Interior Elias Bou Saab said, “The vast majority of smuggling takes place through the legal crossings… (Illegal crossings) are not all used for smuggling goods, as many of these are used for smuggling people on foot.”

“Many of the banned, adulterated, or expired plant chemicals enter Lebanon legally,” says one of the smugglers who refused to reveal his identity, as shipments of imported agricultural medicines that are registered and conform to specifications on paper, are in reality also “loaded” with banned or spoiled products, so customs control and the Ministry of Agriculture cannot detect them since they are relatively small quantities compared to the large 'legal' quantities in the shipment — that is if we exclude the hypothesis that some officials are not implicated in the smuggling process itself.

Merchants openly selling banned products

On the shelves of one of the well-known shopping malls in the southern suburbs of Beirut, in the agricultural tools section, agricultural pesticide packages line the shelves like any other products within access to everyone. A customer holds a package in his hands looking confused. He asks another customer whether the pesticide he is holding is effective against cockroaches within his home. The man suggests another kind, which the client proceeds to purchase and take home, reassured by the other man's advice.

Little does he know that the pesticide he bought contains three banned active ingredients out of the four listed on the package, like Cypermethrin which was banned in 2018, Diazinon banned in 2016, and DDVP banned in 2011. The last one is classified as “highly hazardous and toxic” by the World Health Organization.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classify all these compounds as “likely to, or may cause cancer”. The classification of Diazinon was based on strong evidence that it causes damage to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) or chromosomes.

To verify the claims, we cross checked with the Environmental Protection Agency’s carcinogens list. It became clear that 32 out of the 35 compounds were classified as likely to or may cause cancer, while 11 compounds cause fertility issues and harm fetuses

The label on the product purchased by the customer says that it was “Made in Germany”, but there was no reference to the manufacturer or importer. The same is true for other products containing compounds no less dangerous than those mentioned above, such as Chlorpyrifos or Methomyl, even though decision (92/1) of May 20, 1998 obligates companies to include the name and address of the manufacturer along with the name and address of the importer on the outer label, subject to legal prosecution.

Only one container names the importing company as 'NM' registered under No. (3374). After cross checking the official list of import companies, we found no entry under that name. To confirm this, we addressed our queries to Lama Haydar, the head of the department of phytopharmacology at the Ministry of Agriculture, who confirmed that this company is not registered, and that the ministry registers companies by their names and addresses and does not give them a registration number. She stressed that this product must have been smuggled in and that the institution that sells these medicines is not licensed. Therefore, it has no right to trade in phytopharmacology without a license.

Haydar sent teams from the ministry with security support to inspect the store, and the goods were seized. A report of the violation was filed and referred to the Public Prosecution. The owner of the establishment pledged not to sell or dispose of the pesticides, and to keep them stored in his warehouses or transfer them to the warehouses of the Ministry of Agriculture at his own expense, so they can be destroyed.

Lebanon is not equipped to dispose of banned and hazardous substances due to their harmful effects. It relies on joint projects implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) to destroy them outside Lebanon periodically.

A source in the Ministry of Agriculture says that it had confiscated banned pesticides ten years ago, and stored them in the warehouses of the Ministry’s Kfarshima laboratory, south of the capital Beirut, where they remain today. Haydar confirms that a new project is being prepared with FAO to collect banned pesticides to be destroyed outside Lebanon.

Two months later, we once again visited the establishment selling banned pesticides to ensure that it had complied with its previous commitments, only to discover that it was still displaying and selling pesticides that contain prohibited substances.

How do pesticides affect agricultural exports?

In November 2021, Qatar banned a number of Lebanese agricultural exports from entering its territories due to “the high percentage of pesticide residues, such as E. coli bacteria and lead,” according to a statement by the Qatari Ministry of Health. The United Arab Emirates had banned all types of Lebanese apples in a decision it issued in 2017, which remained in effect until June 2021. Egypt had also announced in 2019 the suspension of a shipment of 700 tonnes of apples for the same reason despite the fact that half of Lebanon’s exports of apples go to Egypt.

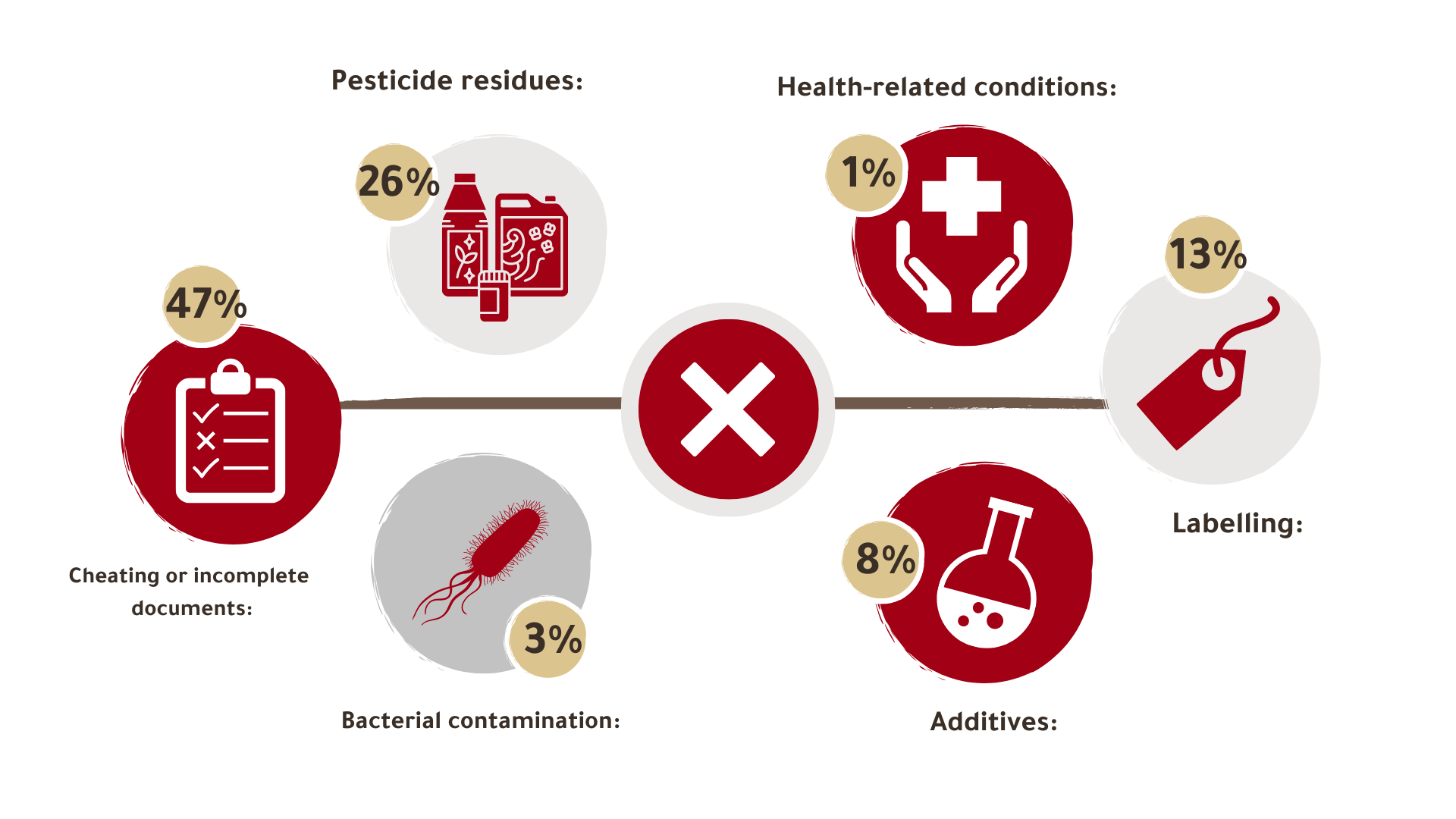

Data from the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) reveal that a quarter of the cases where Lebanese agricultural exports of vegetables to the United States and the European Union were rejected between 2010 and 2018, had been due to pesticides. The organization’s website does not provide information about other countries that Lebanon exports to, especially Arab countries.

We requested similar data from the Investment Development Authority of Lebanon (IDAL), which supports and promotes Lebanese products abroad, especially agricultural products, but we did not get a response when we visited their offices, nor after we forwarded our questions via email as they had requested.

Data from the Lebanese Customs Administration show that there has been a decline in agricultural exports in recent years. Despite a small improvement in 2020, data not yet issued by the Customs Administration expects further decline in 2021, due to the Qatari and Saudi decisions to ban the entry of Lebanese fruits and vegetables to their markets or allowing their transit through their territories, because shipments have been used as a cover for drug smuggling. This is a strong blow, since Lebanon used to export half of its agricultural produce to Gulf Arab countries.

As for agricultural exports to the European Union, they do not exceed 4% of its total agricultural exports, despite the fact that 16 years have lapsed since the signing of the partnership agreement with the EU, whereby Lebanon obtained a complete exemption from customs imposed on its agricultural commodities. But according to a 2015 study prepared by the Centre for Economic Studies at the Chamber of Commerce, Industry, and Agriculture in Beirut and Mount Lebanon (CCIA-BML), “the use of pesticides and fertilizers banned in Europe by Lebanese farmers” has kept the export to Europe minimal.

Health is a priority… And one hand cannot clap alone

Nehme explains that “this reality persists because of a flaw in the chain of control of agricultural pesticides and their use by farmers. The world now has systems like Good Agricultural Practice (GAP), that specify the time and the quantity a farmer must spray each crop in a way that maintains their safety.” Nehme goes on to say, “In Lebanon, however, the farmer is left to his own devices. In all other countries, the state shadows every step farmers make and supports them to help the agricultural sector as a whole and help develop the country.” She adds, “We are now in dire need of preserving food security. We need to even cultivate any piece of land because the cost of imports has become high due to the economic crisis.”

The farmers’ answers to our questionnaire confirm Nehme’s observations, as more than 80% of farmers stated that no one from the Ministry of Agriculture has visited them during the past year or even during the last five years for the purpose of supervision or guidance. Only three of them reported that they had received guidance on the use of pesticides from the ministry, while the rest have stated that they learned how to use pesticides through practical experience, agricultural engineers, pesticides merchants, or agricultural associations.

In the spirit of giving the Ministry of Agriculture the right to reply to our findings, since it is legally responsible for guiding and instructing farmers, examining residues in produce, and monitoring agricultural pharmacies, we sent a letter to the Minister of Agriculture Abbas Hajj Hassan. But to date we have not received a response. In addition to the Ministry of Agriculture, there are seven ministries assigned with the task of monitoring the safety of food in Lebanon. To avoid any conflicts or clash between them, the Food Safety Law was approved, according to which the Lebanese Food Safety Committee was to be formed. Article 29 states that this entity is responsible for monitoring food safety, including monitoring the use of pesticides as well as coordinating between ministries. The head of the committee was appointed in 2018, but its board of directors has not been appointed to this day as required by Article 32 of the law. Therefore, the enforcement of this law is still pending seven years after its issuance.

Who is obstructing the process of forming the committee? Its president, Dr. Elie Awad says, “This issue has not been a priority for the successive governments since 2018, and the ministries concerned with food safety consider the formation of the committee a limitation of their powers.” He explains that it has not begun operating because the government did not complete the appointment of the committee's board of directors, and “One hand cannot clap alone”. He concludes with, “We have reached a situation where it is now necessary to sound the alarm.”

*This investigation was carried out with the support and supervision of the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism network (ARIJ).

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!