Wissam Chahine walks with his son Hani along the road adjacent to the “River of Death”, as he describes it. It is a river that was once a destination for the people of the Na’ameh area in the Chouf district, south of Beirut, before the Lebanese authorities constricted it to one third of what it used to be, in order to build a service road for the Na’ameh-Ain Drafil landfill.

The landfill was created by the state of Lebanon in 1998, to accommodate incoming waste from Beirut and Mount Lebanon regions, and then closing it down following popular protests in 2016. Wissam, a member of the Na’ameh municipality and a forty-year-old father to a child who was diagnosed with cancer, tells Raseef22 that he calls the river the “River of Death,” because it carries with it all the toxins of the landfill that had afflicted his son, just like they had infected many of the people of his town alongside the neighboring towns and villages.

“I Lost Four Years of My Life”

Hani, 14, who has been recently cured of cancer, slowly walks beside his father as he limps on his right leg. The athletic kid who plays soccer, swims, and rides horses, had one day suddenly found himself on a hospital bed undergoing chemotherapy.

One day in 2020, Hani noticed that there was a lump in his leg, and subsequent medical tests revealed that he had sarcoma, a rare type of cancer that affects the bones and the connecting tissue, such as muscles and blood vessels. He tells Raseef22, “I lost four years of my life to illness, and subsequently fell behind in the sports I used to play.”

Hani was the face of a “revolution” — as he described it — that was aimed at fulfilling the promises made to the people of the Na’ameh area and its vicinity, including promises of them getting compensation for the effects of the landfill on them.

The child recalls the spark of this “revolution”, and recounts that “one night in July 2021, following weeks of chemotherapy, I went back to my house that was on the eighth floor in one of the buildings, and the electricity was out.” He adds, “That night I could not sleep because of the heat. The next day, I, along with my father and the people of the area, headed towards the entrance to the landfill, where we held a protest and cut off the road, and then we went to the company that distributes electricity in the area.”

“We Have Become the Scum of Society!”

Their demand at the time was just one, according to Wissam, “And they promised us in 2016 that they’d create a plant to produce electricity from the gas emitted from the landfill, and that they would supply the area with free electricity 24 hours a day as compensation for the damages that had befallen us from the presence of the landfill. But this did not happen. They did build the plant and put it into operation, but we only got electricity for a short period of time.”

He points out that “our cries were heard and heeded, especially following mounting pressure from the cutting off of electricity and water in larger parts of the Chouf district.” He concludes, “They displaced us health-wise, and we became forgotten as soon as the landfill was closed. Before they closed it, they had tried to appease us in a number of ways. But when they closed the landfill, it was as if we became the scum of society, and no one asks about us or our situation.”

In addition to suffering from the landfill and its negative effects on the environment, health, and the overall image of the region, residents of the areas near the landfill are also suffering from “false promises”, as Pierre Farah, 44, explains.

Pierre owns a car rental business, and he is an environmental activist and one of the founders of the “Kafana Nefayat” (‘Enough Waste’) association, which contributed to the closing of the Na’ameh landfill around seven years ago. He lives in Beirut and on holidays he visits his village, Ain Drafil, where most of the landfill’s lands are located within its territory.

Pierre tells Raseef22 about his experience with the promises from the Lebanese authorities, “They promise and do not keep any of their promises. They promised to sort the waste but they didn’t deliver. They were burying the waste as it was without any real waste treatment, so gasses, odors, insects, and diseases spread, and they even dumped more than triple the amount that they had originally requested to dump.”

He goes on to add, “They also promised that the landfill was only a temporary solution for just a few years, but then they continued to postpone its closure for more than 18 years.” In addition, “they have recently promised us to produce electricity from the methane gas emitted from the landfill, but then only provided us with electricity for a limited period of time.” To make the crisis worse, “Today they burn gas in the air while people live without electricity.” He concludes, “Political officials are only good at false promises.”

The Gas is Odorless... Silently Killing Us

“They are silently killing us with the gas that is being emitted without anyone being able to feel, see, or smell it,” Pierre says about the methane gas and its effects on the people of the region. He continues, “This gas, which is one of the main causes of climate change in the world, burns up in the air or is being emitted without any treatment. As a result, agricultural products as well as pine and olive trees have become dehydrated and have become ‘spoiled’ on the side of the landfill.”

He adds that those who live off of agriculture in the area are talking about a strange phenomenon that has been affecting crops and damaging them, and they are trying to treat them with medicinal solutions, but to no avail. They have been quoted to say, “Our entire lives we have been planting and growing (crops), and we have never seen what is happening with us today.”

They displaced us yet we became forgotten as soon as the landfill was closed. Before closing it, they tried to appease us, but when the landfill closed, we became rejects of society, no one asks about us

The effects of methane gas have not only been limited to crops, but also directly affect the health of the locals. Speaking on this issue, Pierre recounts how his brother and his family visited the region for a few days, and they began having symptoms of nausea and diarrhea from the air pollution, according to the diagnosis of their treating physician.

He also points out that “the residents are suffering from unusually severe burns when exposed to sunlight, as if the gas is scalding our bodies without us even feeling it.” He then concludes, “The gas is odorless and has no smell, so people do not feel it while it slowly and silently kills us and our environment. The situation is scary here.”

“These Health Complications Will Persist and Increase”

The health effects of the landfill on the residents of the surrounding areas after its closure, was the title of a study conducted by the American University of Beirut in 2017, but was not published at the time. MP Dr. Najat Aoun Saliba, a deputy elected in the latest parliamentary elections (2022), from the Chouf-Aley district, where the landfill is located, reveals to Raseef22 the results of the study that she had taken part in preparing as the head of the Nature Conservation Center at the university, following a number of reviews from residents of the areas near the dumping ground.

The study was based on interviews with about 2,720 people from the local residents, especially among people from the areas closest to the landfill, and subsequently those exposed the most to the polluted air that it emits and from areas further away from it.

The study notes an increase in the recognition of some health complications and in their severity, in parallel with the rates of exposure to gas-polluted air. Some of the medical symptoms recorded by the study include: ringing in the ears, a persistent cough, frequent colds, nausea, swollen legs, skin rashes, and peptic ulcer.

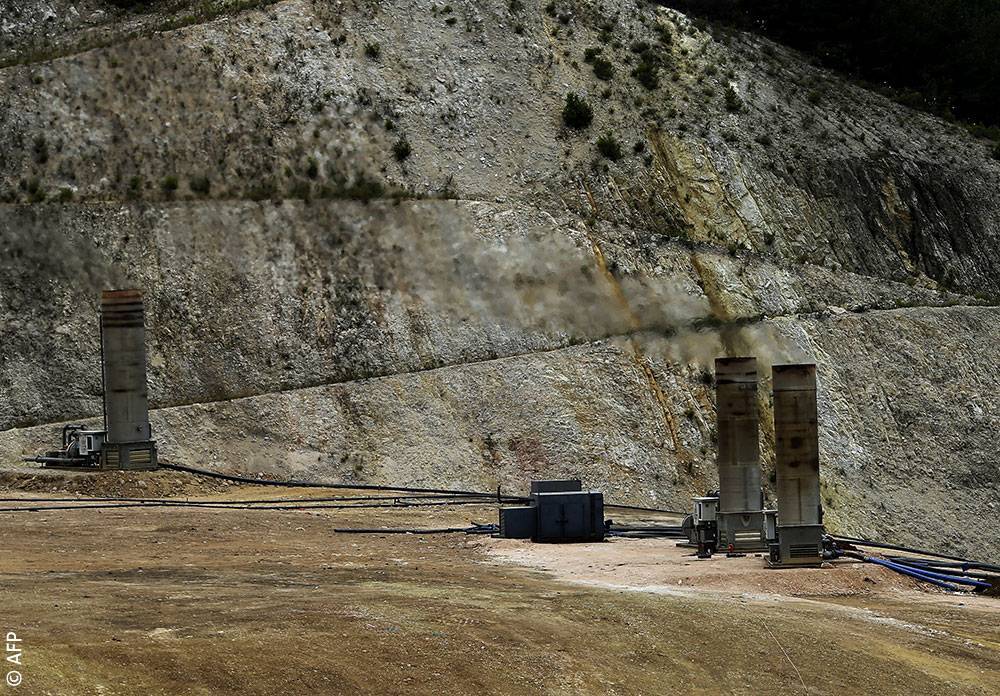

Smoke from burning gas from the Na’ameh landfill on June 16

Aoun Saliba points out that these symptoms, along with others such as mood swings, memory loss, and headaches, are linked to the methane emissions that result from the fermentation of waste in the landfill. She warns that these health complications and symptoms will persist and further increase if the emissions remain unchanged. Therefore, what is required is to stop venting the gas, or burning it up in the air. She wonders, “Why are they depriving Lebanon and the region of this free energy resource? Why hasn’t EDL (Électricité du Liban) to this day outsourced the project to any company based on the bidding tenders that have been made?”

Higher Cancer Rates

“Seven years after the landfill was finally closed down for good, the neighboring areas are still suffering from its negative effects,” Micheline Matar, lawyer and deputy mayor of Na’ameh, says to Raseef22. She adds, “The worst of the effects today include the gas that is being emitted into the atmosphere, which affects the air, the environment, and the crops, in addition to the flooding of the Na’ameh river in the winter due to the constricting of the river to create the landfill, and the spread of foul odors in the village when the waste leachate (fluids) are transported from the landfill to the Al Ghadir station (treatment plant).”

She explains that “the effects, before the landfill was closed down, used to include bad odors, the spread of waste leachate on the roads, and their leaking into our groundwater, in addition to our people suffering from skin allergies, lung diseases, and cancer.” She comments, “We lost our best youth to diseases brought about by the pollution.”

Dr. Roger Abu Serhal, a doctor in his forties specializing in cancer and oral surgery, and one of the residents of the region, adds that when he graduated in 2001 and began practicing medicine, the landfill had already been opened despite strong opposition from the locals. He began to notice higher numbers of cases of medical conditions and ailments in people in the region relative to other regions, such as asthma, respiratory problems, strange skin mutations, and infertility, in addition to recording cancer cases at high rates in children and adults, as well as recording deaths from cancer at rates higher than the general rates. But no exact numbers can be reported on this.

“No One Cares For Us”

One of the people suffering from such medical conditions is Nuhad Abu Nasr. The wife of the mukhtar of Na’ameh (elected head of a village, town, or neighborhood ‘mahalle’) and one of the first people to object to the landfill, Nuhad, 64, suffers from lung disease. With a long and pained sigh, she starts telling her story to Raseef22, and begins talking about the lung disease that has worn her body out. She says, “My condition is dismal. I cannot walk without a cane or crutch. I breathe with difficulty and can barely speak, and if I hadn’t wanted to speak out about our pain and suffering from this landfill so much, I would have preferred not to talk at all, since it tires me greatly.”

Nuhad describes the dumping ground as “the landfill of death”, and says that she is not the only one who is suffering from its effects on her health. Rather, “countless” residents of the neighboring areas share her hardship.

Methane gas is being burned in the air and is emitted without any treatment. The gas is odorless and has no smell, people can’t feel it while it slowly and silently kills us and our environment. The situation is scary

Nuhad was one of the first people to raise their voice against the construction of the landfill in 1998. Those opposing the project were met with repression at the hands of security forces that would forcibly open the roads they blocked. She recounts, “Family friends and relatives used to call me from America to tell me that I had made them cry. Yes, even the farthest people all over the world wept and felt for us, except here. In Lebanon, no one feels for or cares about us. Here, only ‘Bou Khansa al-Zarqa’ listens to us.” She explains that the name “Bou Khansa” means God, and adds, “Every person on earth can sell us and sell our rights for money.”

Nuhad recounts that they were displaced from their home in Na’ameh in 1984 due to the war, and were only able to return years after it ended in 1994. She says, “We went back and there were no houses to live in, some were destroyed and others were burned down. We rebuilt everything from scratch, and less than five years later, the authorities opened up the landfill. It was as if they wanted to displace us again. Every once in a while there is a brand new blow to force us to be displaced, the latest of which is economic displacement these days.” She adds, “We no longer have the power to even feel. We feel like we are as good as dead on the inside.” Here, she stops the interview since it has worn her out by saying, “I’m tired, I want to stop talking now.”

“We Came Back After the War Then Were Displaced Again”

Between Wissam’s talk of feeling like “the scum of society” and Nuhad’s words about repeated displacement, Micheline Matar adds that the Na’ameh region has become stigmatized with the name of the landfill, which is causing moral and psychological harm to its people and its youth who do not think of investing in their own region in the future. She adds, “It was a displaced and abandoned village due to the war, and it wasn’t long after we had returned that we were once again displaced.”

Trucks dumping waste at the Na’ameh landfill, on March 30th, 2016

What about the role of the municipality? Was it originally lenient when the landfill opened, and then when it began to register violations in the way it was managed? The deputy mayor answers, saying, “The landfill was imposed upon us, without the municipality having the ability to accept or refuse. We have written to the relevant authorities, but no one answers or responds.”

Matar lists the promises the municipality had received from the central authorities without any real commitment on their part to fulfill them, “For example, they promised us to build a support wall along the banks of the river, to avoid its flooding every winter, since there is a confluence of rivers in Na’ameh, and the riverbed has been narrowed down to its third. However, the municipality still spends more than two hundred million pounds annually to treat the effects of the flood, while there is no response from the central authority.”

She says that they feel a great injustice, “We are oppressed. They opened the landfill by force, disfigured our river and environment, and damaged the health of our people and the reputation of our region. We have endured the waste from all areas of Beirut and Mount Lebanon for 18 years, and after all of that, they saw that it would be too much to fulfill the promise they had made as compensation, which is to give us free electricity. The plant has been shut down for years, while people are drowning in darkness and inhaling the toxic gas that is being emitted from the landfill and is being burned up in the air.”

From the Local Level to the National Level

In the face of this overwhelming feeling of injustice, why don’t the residents of the area mobilize? Speaking on this to Raseef22 is Fouad Yahya, a forty-something engineer and an environmental activist that was one of the founders of the campaign aimed at closing the Na’ameh landfill in 2013.

Fouad returned to his hometown of Ain Drafil after many years of being an expatriate in the country of Qatar, and says that he worked abroad to build a house that he was never able to live in. He tells of a situation that provoked him, and made him decide to work on closing the landfill. The story began with a dispute that had taken place between him and his business partner as a result of a lawsuit, and at one point during the dispute he had told him, “The leader of your region, Walid Jumblatt, is forcing you to live on trash, and you have never once objected. But today you are trying to object here, and file a lawsuit against me?!”.

Fouad backtracks to the beginnings of the activity aimed at closing the landfill. He got to know people from more than one area near the landfill — from Dohet El-Hoss to Aramoun, Baaouerta, and Na’ameh — who were passionate about the work they were doing. They came together and have been working hand in hand since 2013. These people were not the only ones affected by the landfill, but what distinguishes them, according to Fouad, is that they are self-employed and do not have any material benefits or ties to any of the parties controlling the area. He says, “When the people of the area objected to the landfill, the parties in control would intervene to silence them or bribe them with a job, financial assistance, or in-kind assistance. One of the municipal leaders was even receiving money for providing legal advice to the Sukleen company, the operator of the landfill.”

For Fouad, the landfill could not have been closed down without moving the issue from the local level to the national level. Therefore, he, together with activists in the campaign, developed an elaborate plan to carry out a strike, timing it with the renewal of the Sukleen contract for operating the landfill in 2015.

In the beginning, they mobilized people who were disgruntled and affected by the presence of the landfill with them, and gave them priority in media appearances and exposure. They also worked on uncovering the accounts and the unimaginable profits that Sukleen makes and are directly deducted from the funds of municipalities in Lebanon. They also contacted associations concerned with combating pollution and corruption, and tried to embarrass the parties and actors in the region by requesting their participation in a one-day protest movement. On the day of the protest, these parties and actors were shocked by the number of people who participated, which shamed them and discouraged them from continuing to apply pressure to stop the movement.

At this time, activists in the campaign investigated the absorptive capacity of Sukleen’s sorting plants, and calculated how many days they would need to flood the streets of Beirut and Mount Lebanon with trash. Two days were enough to carry out their strike, which was enough to move their cause from the local level to the national level.

On the day of the protest, activists announced the closure of the Na’ameh landfill. Indeed, two days later, the streets of the capital Beirut and the areas of Mount Lebanon were flooded with garbage. This incident, according to Fouad, was enough to mobilize the media and public opinion over their cause. After a lot of give and take that included the forced reopening of the landfill for a limited period of time, the landfill was permanently closed down in 2016, 18 years after it was opened.

‘Marginal and Marginalized’

Claude Jabr, a political activist in his forties and one of the founders of the “You Stink” campaign, which sparked a nationwide movement on the issue of waste in 2015, recalls that the landfill near his residence has been there ever since he was a young child.

Claude lives in the Bourj Hammoud area, which holds on its shore one of the oldest and largest landfills in Lebanon. He says, “We always smell foul odors, and people die of cancer and get lung and skin diseases”. He then adds, “This time, enough is enough, especially with the spread of garbage in the streets and the decision to reopen the Bourj Hammoud landfill as an alternative solution to the Na’ameh landfill. So I have decided to act, especially since the company that handles the waste treatment — ‘Sukleen’ — would usually create a crisis during which it would flood the streets with garbage whenever its contract with the state was about to expire, that is, every four years, with the aim of exerting pressure so that it would be extended once again.”

The fishing port of Bourj Hammoud, near the landfill

Claude talks to Raseef22 about the collusion of the controlling parties in the area with the central authority to allow the landfill in his area to be put back into operation during the period that the Na’ameh landfill is closed down. He says, “The Tashnag party was lying to the people of the area by claiming that they would turn the area into a region filled with skyscrapers, and despite the spread of foul odors, the people were afraid of confrontation because they might lose their jobs and were worried the dominant party would close their shops and businesses.”

He recounts the story of what they had encountered during their field visit to the area. They had come across a displaced family from Syria that lives at the entrance to the landfill, and all of its children were suffering from skin ulcers on their faces. He says that people in these areas act on the basis that “nothing can change, and they just have to adapt to the situation.”

Claude quotes his father and mother, who are in their late sixties, saying that “the landfill has been there ever since they lived in the area during the Lebanese war, and it is a reality, as if it is part of the view and cannot be changed.” They would ask him, “Do you really think you can bring about change? Nobody can!” Claude concludes, “The waste dossier is related to the political and sectarian quotas of the ruling mafias, and people began mobilizing in August 2015 because they saw that this crisis affects all of them.”

The Power Plant Not Operational Despite the Electricity Crisis

Residents of the areas adjacent to the Na’ameh landfill are unanimously demanding restarting operations in the electricity plant and feeding their areas additional hours of electricity. With the reopening of the Na’ameh landfill in 2015 for a period of time, the residents were promised in return that a plant producing electricity from the methane gas emitted from the landfill, would be established. They were promised it would provide free, clean electricity 24 hours a day to the neighboring areas, by adopting clean energy, that is, generators that burn gas completely and reduce toxic emissions.

Engineer and member of the Board of Directors of the Electricité du Liban (EDL), Samer Slim, tells Raseef22 that the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), which runs the landfill, contracted the Lebanese company Clean Energy Solution (CES) in 2016, in alliance with the GEE Global company, to build a 7-megawatt electricity power plant and operate it for an entire year. But the company continued to operate the landfill until 2020, by extending the main contract with reconciliation agreements with Electricite du Liban (EDL).

This extension took place due to canceling the outcomes of two bidding tenders conducted by the corporation during this period. In 2018, a tender was held for operating the plant, and three companies applied to it, one of them was CES, while the other, Middle East Power (MEP), won the bidding tender at a price of nearly seven million dollars over five years, by a difference of three million dollars from the offer made by the competing company, according to what the COO of the company, Yahya Mawloud, has disclosed to Raseef22.

The electricity company had sent the results of the bidding tender to the Ministry of Energy, headed by Minister Cesar Abi Khalil of the Free Patriotic Movement (FMP), as well as to the Ministry of Finance for approval. The Ministry of Energy responded with refusal. A member of the Board of Directors of EDL explains that the refusal came due to some flaws in the bid submitted by MEP. The most prominent flaw, according to Slim, lies in the comprehensive maintenance clause of the generators that require maintenance every 20,000 operating hours, and the use of original spare parts, both of which MEP had not clearly pledged to do in its proposal.

But the company’s Chief Operating Officer, Yahya Mawloud, says the company would have signed the same contract that any other company would have agreed to, and would have adhered to the conditions put in place for maintaining the generators. He relates the reason for canceling the bidding tender to the political differences that had arisen between him and Minister Abi Khalil, for his criticism of the Free Patriotic Movement’s management of the Ministry of Energy, and for him talking about the corruption related to this and that have to do with deals for electricity-generating ships (floating power plants docked off the Lebanese coast).

As a result, the bidding tender was canceled, and CES continued to operate the plant with the reconciliation contracts that EDL was signing with the private company until the end of 2019. In 2019, EDL held another tender, and this time the operating company CES, and MEP were the only ones that submitted proposals. According to Salim, “One of the terms of the tender appears to have been set to exclude CES, and is a requirement for having experience in operating similar plants for a slightly longer period than what CES has acquired.”

Demonstrations from the “You Stink” movement

In the year 2020, the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) handed over the plant to Electricité du Liban, which in turn did not receive any reply from the Ministries of Energy and Finance regarding the second tender. So the tender was canceled for the second time, and this time the situation became worse with the intensified rationing in the electricity within Lebanon, up to 23 hours a day. This situation prompted the people, headed by Wissam and his son, to vent out their anger on the streets in July 2021, and to exert pressure in order to secure a few more hours of electricity.

On this, Slim says, “It is unacceptable that we lose 20 thousand dollars a day because of the suspension of a plant that produces 6 megawatts from a free source of energy. That is why, Electricite du Liban negotiated with CES, and they reached a contract by mutual consent to purchase the required spare parts to secure comprehensive maintenance for the plant for a period of two years, in addition to training employees of Electricite du Liban to operate it.”

According to Slim, the cost of the contract signed with the company amounts to three million US dollars, and the amount will be secured from EDL’s share of the “special drawing rights”, or the SDRs that the state of Lebanon is entitled to get from the World Bank. It is worthy of note that Electricite du Liban signed the contract by mutual consent hours before the Public Procurement Law went into force on July 28, 2022, otherwise it would have had to pass under the judgment of the Public Procurement Authority (PPA) established under this law to conduct a new bidding tender for operatinf the electricity plant. This means losing even more time, while the plant is still not operational.

On this, Mawloud comments that “the administration today has preferred to cancel the result of a tender twice, and waste a free source of energy and burn it up in the air, with all the pollution that this causes, in order to give a contract to a company that has lost the bid twice.” He asks, “How can they sign a contract worth three million US dollars to operate the plant for two years, when our offer does not exceed six million US dollars for five years?” It is noteworthy that the companies of Mott MacDonald, Sukomi, and CES, have received around 14 million and 300 thousand US dollars through the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) over the course of five years to establish and operate the plant.

Over $1.89 Billion in 20 Years

Where is the Ministry of Environment concerning this issue? Raseef22 asked the Minister of Environment, Dr. Nasser Yassin, who said that he intervened last winter to ensure that the gas in the landfill was vented, after the company operating the electricity plant halted operations, amid fears that the landfill would explode.

What will guarantee that the landfills that are proposed will not turn into another version of the Na’ameh landfill, where waste was dumped without proper treatment despite the Lebanese state spending more than $1.89 dollars over 20 years on "treatment"?

Yassin pointed out that venting or burning up methane in the air has serious implications for climate change in the region. He says that at the last climate summit, Lebanon committed itself to reducing methane emissions, hence the necessity of addressing the Na’ameh landfill emissions.

He pointed out that the Na’ameh landfill has other implications linked to how to treat the leachate resulting from the fermentation of waste, since the current treatment being employed is very primitive in light of the financial crisis, and there is a real fear of the leachate leaking into the groundwater.

As for the ministry’s plan to treat waste in the coming period in light of the financial crisis, the Minister of Environment lists his ministry’s directives to encourage sorting at the source as well as secondary sorting through municipalities and municipality unions, in order to convert waste refuse into energy through RDF technology, and to create about 12 new landfills. He says that the way to achieve these steps lies in the governance of the sector through the establishment of a national authority for solid waste management and in securing the cost by adopting the principle of cost recovery directly from the population.

In relation to this plan, what will guarantee that the landfills that are proposed by the Ministry will not turn into another version of the Na’ameh landfill, where waste was dumped without any proper or serious treatment despite the Lebanese state spending more than $1.89 dollars over the past twenty years (the cost of the contracts for waste collection and treatment between the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR), Sukleen, and Sukomi, according to Gherbal Initiative figures). Regarding these fears, the Minister of Environment responds that he will adopt separating the management of the landfill from that of the sorting plants, in addition to providing financial incentives to encourage the local authorities to sort, so that the landfilling process would be the most pricey course of action.

The Environment Ministry’s plan was approved in April 2022 in the Council of Ministers, before it was turned into a caretaker government. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the next government to issue decrees to form a national solid waste management authority. Meanwhile, at this point in time, the act of open-air combustion and burning of waste has resurfaced in some Lebanese regions.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!