Umm Mohammad first heard of Lebanon when she was nine years old, after their neighbor in Haifa told her that his family originated from the Lebanese city of Tyre. Suddenly, things took an unexpected turn, and she, along with her family, abruptly became visitors to the relatives of their old neighbor, Abu Ali.

Umm Mohammad recounts to Raseef22 her escape from Palestine on foot upon the invasion of her homeland by Zionist gangs in 1948, and talks of the horrors she had to live through. She narrates everything in great detail as if it had only taken place yesterday and not some 73 years ago.

Umm Mohammad’s family headed for the northern borders of Palestine, in hopes that they would return to their homes after the Arab Liberation Army expelled those who would later come to be known as “Israelis”. Or so everyone thought.

Umm Mohammad describes how they lived in a house in the heart of Tyre, but her father decided to go to Bint Jbeil, a town located along the southern border of Lebanon, to shorten the distance that they would soon have to take on their way back home.

But things did not go the way he thought they would. In Bint Jbeil, the Lebanese authorities first forced him to board a bus and then a train along with other refugees, and took them towards the Syrian border. But the authorities in Damascus denied them entry, so the family found themselves in the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in 1949 near the city of Tripoli in northern Lebanon.

With the growing influx of Palestinians fleeing Zionist gangs, terrorized by their acts of violence, the International Red Cross (ICRC) and the American Quaker organization established camps to accommodate them. Following a year of displacement, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) was established by a decision of the United Nations General Assembly, thus assuming the responsibility to care for those who have been forced out of their land, and to provide them with food and relief services. The Palestinians in Lebanon became refugees residing on plots of land rented by the agency.

Abdelnasser al-Ayyi, director general of the “Lebanese Palestinian Dialogue Committee” - a governmental body established in 2005 that deals with public policies that target Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, and acts as a central link between Palestinian refugees and official and international institutions - points out that “this stage was a very difficult one for the host country, given that it only gained independence in 1943 and its institutions were not ready to host 100,000 Palestinians and provide them with the necessary services.”

The Palestinians were not the only ones who poured into Lebanon. Jaber Suleiman, a Palestinian independent researcher in refugee studies, points out that “tens of thousands of Lebanese people who had been working in Palestine at the time were displaced along with the Palestinians, so the burden was a heavy one.”

Suleiman tells Raseef22 of the Lebanese government’s decision to set up refugee camps on the outskirts of cities and not in the countryside, in order to benefit from the skilled Palestinian labor, especially since a large number of refugees had skills that Lebanon needed, and some of them were well-off and had brought their money and gold with them.

Many sectors in Lebanon flourished with the arrival of the Palestinians, “especially banking, industry, agriculture, and the flow of trade.”

But then began marginalization. Suleiman believes that “placing the refugees in camps that are cut off from the Lebanese environment and are more like ghettos, was the beginning of the intended marginalization of the Palestinians.”

The Lebanese authorities granted citizenship to thousands of Christian Palestinians, according to Suleiman, in “clear sectarian discrimination”, while “special presidential decrees granted citizenship to wealthy and affluent refugees, regardless of their sect.”

A past that shaped the future

Back to Umm Mohammad, she married in the fifties, and moved to Tal al-Zaatar refugee camp, east of Beirut. She says, “Life went on, and the camp became something that resembles a farm surrounded by wires with a gate that a soldier stands by, allowing entry to some and refusing others.” She adds that “the man from the second office (Lebanese army intelligence) used to arrest and torture whomever he wanted and prevented women from access to water and (public) bathrooms.”

Speaking of that period, Jaber Suleiman says that, “Lebanon was a police state during President Fouad Chehab’s era, and this security hold included everyone, but it was especially severe on refugees, so there was repression and marginalization, even though the sixties witnessed economic affluence due to the smuggling and transfer of funds from Arab countries witnessing total expropriation, and which were invested in banks or in private interests, in addition to the Palestinian bourgeoisie launching many projects.” Suleiman refers to a report by the Arab Higher Committee dated December 18, 1959. The report stated that the value of the funds that were transferred to Palestinians in Lebanon was equivalent to “three times the entire annual budget of Lebanon.”

The cumulative effects of marginalization and security dominance over the Palestinian camps, along with the rising influence of Palestinian organizations and their own growing tendency for military action against Israel following the defeat of 1967, prompted the refugees to carry out a popular “revolt” or “uprising” that resulted in the signing of the Cairo Agreement in 1969 between Lebanon and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and under the auspices of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser. The accord stipulates “the right to work, reside and move around” for Palestinians residing in Lebanon, “the establishment of local committees comprised of the Palestinians in the camps to take care of the interests of the residents”, and the establishment of points for the Palestinian armed struggle inside the camps in order to handle regulating and defining the presence of weapons in the camps, as well as “allowing Palestinians residing in Lebanon to participate in the Palestinian resistance”, embarking on operations against Israel from Lebanon.

Thus, the Palestine Liberation Organization gained wide influence inside Lebanon, which later increased with the arrival of a large group of fighters that had been expelled from Jordan after clashing with the Jordanian army in September 1970.

Umm Mohammad recalls how her husband and her brother joined the training camps of the “Fatah” movement in the Arqoub region, south of Lebanon. “During those moments, we felt dignified and refugees became freedom fighters,” she said.

The Secretary-General of the PLO factions in Lebanon, Fathi Abu al-Aradat, explained to Raseef22 that “the refugees lived through a difficult period before the organization became present in Lebanon, and they had been suffering from deliberate oppression,” noting that the camps later turned into “a human reservoir against occupation”. He also said that the “Palestinians shared the struggle with the Lebanese people, but right-wing (Lebanese) players and regional parties rejected this completely, and the repercussions were great.”

Umm Mohammad recalls how, in the 70s, her husband and brother joined the training camps of “Fatah” movement in south Lebanon. “At that time, we felt dignified and refugees became freedom fighters”

The people of Lebanon became divided between those supporting Palestinian freedom fighting and those who oppose it on the grounds that their actions violate Lebanese sovereignty and will subject Lebanon to Israeli acts of retaliation. Fear of the PLO’s influence in Lebanon also grew among the Christians, causing things to take a turn for the worse as tensions rose.

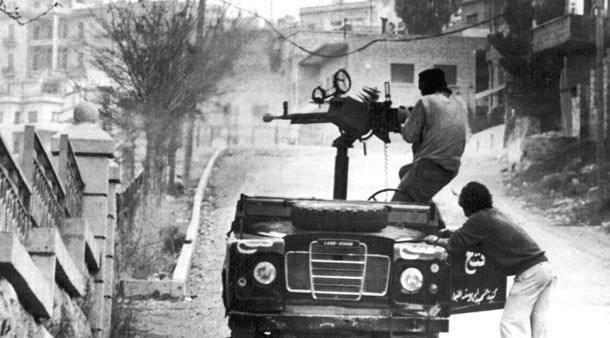

With the outbreak of the Lebanese civil war, the division became much clearer: the Lebanese National Movement (LNM) - comprised of leftist and nationalist parties - and its ally, the Palestinian Liberation Organization, clashed with the Lebanese regime and what was, at the time, called the “Lebanese Right” and made up of Christian parties.

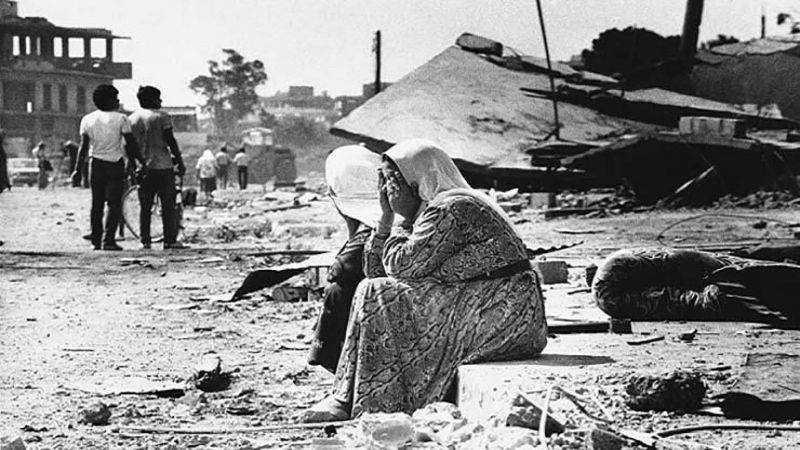

The conflict between the two sides dragged the refugee camps into the center of the bloodshed. One of the results included the 1976 siege and destruction of the Tal al-Zaatar refugee camp, which was located near Christian neighborhoods. Umm Mohammad recounts this chapter of her story, saying that she “hated the color red because of all the blood”. She was displaced once again and headed to the Shatila refugee camp in Beirut, where her son was staying while studying medicine at the Beirut Arab University.

But misfortune visited yet again. In 1982, Israel besieged West Beirut, which led to the expulsion of PLO fighters from Lebanon. The Palestinian refugee camps were left unprotected, and in September of the same year, the horrific Sabra and Shatila massacre took place. The massacre was done at the hands of Israeli forces as well as groups from the “Lebanese Kataeb Party” and the “South Lebanon Army” (Lahd pro-Israel militia), lasted for three days, and left hundreds of Palestinian and Lebanese people martyred.

Umm Mohammad says that she was “lucky” because she hadn’t been in Shatila at the time of the massacre, after her sister insisted that she and her children stay over at her house in the Burj al-Barajneh refugee camp. Nonetheless, she had to suffer through the consequences of the massacre when she came across the bodies of the victims while searching for her missing husband who she later found with a friend in the Tariq el-Jdideh area, and when she lost her home that was located on the outskirts of the devastated camp.

Palestinian refugees were subject to very difficult conditions following the exit of the PLO from Lebanon. “There was a sort of Israeli and Lebanese revenge against civilians,” says Suleiman. Perhaps the greatest hardship they faced there was during the three year-long “War of the Camps” that took place from May 1985 to July 1988 between the Fatah movement in the Palestinian refugee camps in Beirut and the Syrian-backed Amal Movement led by Nabih Berri, in addition to some Palestinian factions backed by Damascus. These battles resulted in the complete and total end of Palestinian influence in Lebanon.

Perhaps the greatest hardship Palestinians faced was during the 3 year “War of the Camps” that started in May 1985 between Fatah and the Syrian-backed Amal Movement led by Nabih Berri, ending all Palestinian influence in Lebanon

Abdelnasser al-Ayyi indicates that the Lebanese civil war, as well as its events and conflicts are still very much present in the memory of the Lebanese and the Palestinian people, and “despite the removal of the divides, its burden is still a heavy one in both the conscious and subconscious of both sides”. Al-Ayyi also notes that “the Lebanese relationship with the Palestinians began with a wave of sympathy then a civil war phase and accusing them of causing the war”, and then “implementing the conditions of defeat on the Palestinians” following the end of the civil war.

Ahmad Abdel Hadi, the representative of the Hamas movement in Lebanon, says that “the suffering of the Palestinians in Lebanon and their deliberate marginalization by the state of Lebanon goes back to history without looking towards the future. The civil war has ended but its repercussions did not.”

Marginalizing laws and practices

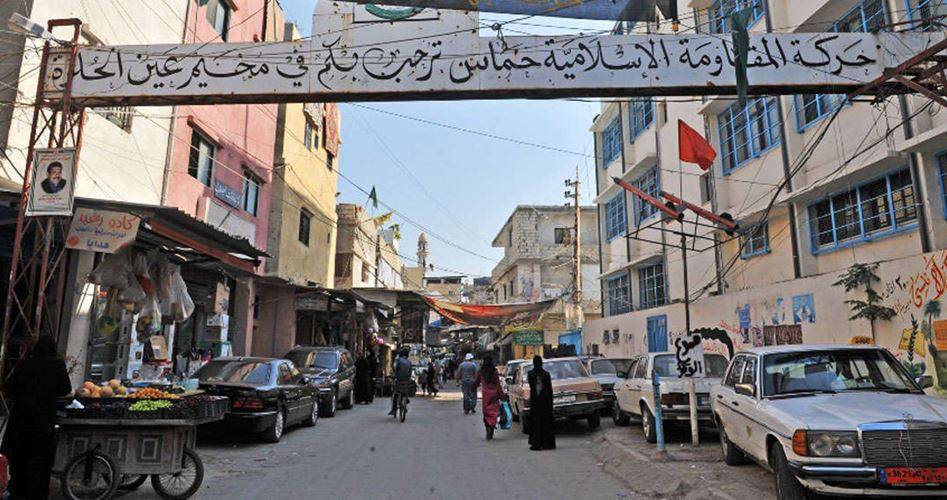

Umm Mohammad’s husband lost his life during the War of the Camps in the siege of the Burj al-Barajneh refugee camp. She was forced to move to the Ain al-Hilweh refugee camp to live with her daughter. She is currently surrounded by her children and grandchildren in a three-story house that is in dire need of renovation, but Lebanese authorities are refusing the entry of construction material into refugee camps in southern Lebanon for security reasons, she says.

She asserts that she “has not had a single nice day since leaving Haifa, and I hope that the children will see better days than the ones we had.”

But her wish seems to be unrealistic. Her grandson Ahmad is married and has two sons, but he does not work on a regular basis. He had lost his job in a plastics factory two years ago after their employer decided to reduce the number of employees “without providing any compensation or warning before the arbitrary dismissal”.

If this current reality of Palestinian refugees continues, it'll lead to societal implosion. Therefore “the issue of rights is in the interest of Lebanon more than Palestinians, because it stabilizes the Palestinian issue and prevents its detonation”

Al-Ayyi indicates that “the suffering of a Palestinian begins with the absence of his ‘legal personality’ in Lebanon. The authorities recognize him as a refugee, but he lacks his personality and identity when it comes to laws and when brought before the judiciary. Here, we discover the discretion when dealing with him, as sometimes he is treated as a foreigner, sometimes as a stateless person, and sometimes as an Arab citizen. As such, there isn’t any interaction where rights and duties are actually made clear, so he is deprived of his basic human rights, and this would result in the refugee losing the feeling of belonging to Lebanon and acquiring a feeling of permanent apprehension of the future, as no justice is achieved for him. In short, he lives on the margins of the law because his presence is not linked to legal legislation.”

The Lebanese Labor Law issued in 1946 had stipulated that Palestinians must obtain a work permit, or that the principle of reciprocity is applied to them, and “this isn’t attainable because they do not have a state,” explains Suleiman. He then adds that “the law was amended in 2010 by Parliament, who removed the principle of reciprocity but kept the condition that they must obtain a work permit.”

On the other hand, a law regulating the Employment of Foreign Persons (aka Decree No. 1756) was issued in 1964. In Article 9 of the decree, it stipulates that “the Minister of Labor and Social Affairs, during the month of December of each year, determines... the jobs and professions that the Ministry deems necessary to restrict them to only Lebanese people.” This affects Palestinians residing in Lebanon, explains Suleiman, “and accordingly, refugees are prohibited from working in professions restricted to the Lebanese people, and these professions can be changed on an annual basis depending on the directions of the designated minister. Therefore, the number of professions that are specifically prohibited for Palestinians is still unknown, as it may range between 38 and 70 job titles depending on the discretion of the minister and his annual decision.”

There are also professions, such as medicine, law, pharmacy, and engineering, that legislation restricts the practice of, within unions that a Palestinian cannot be a part of, because their internal regulations and rules of procedure require that their members are either Lebanese or carry the nationality of a country that deals with Lebanon in reciprocate treatment.

Suleiman laments that “there are not enough studies to explain the Palestinian role and its contributions to the Lebanese economy, knowing that the Palestinian worker is competent, spends his salary in Lebanon, and doesn’t transfer it abroad. Refugees are not a burden, but are rather agents of development if properly employed. Currently Palestinians are working in the black market for low wages without any health insurance or social security coverage.”

Ahmad helps his uncle, a dentist, organize and schedule patients’ appointments at his clinic in the Ain al-Hilweh refugee camp. His uncle the doctor embodies yet another problem that Palestinians in Lebanon suffer from, as they are prohibited from opening certain shops and businesses, clinics included, outside the refugee camps. Dr. Khaled wishes that he could move his clinic to the city of Sidon, “Prices and expenses are different now, and I can make a living from the clinic alone, without having to work for a Lebanese doctor or in various clinics under a false name in order to earn some money.”

Dr. Khaled, like many other Palestinian doctors, works in Lebanese institutions by impersonating the identity of a Lebanese doctor by previously agreeing with him to share the resulting financial profit between the two. Basically, the Lebanese doctor sells his name for a few hours and earns money without having to work.

The long list of restrictions imposed on Palestinian refugees include their inability to purchase a house outside the refugee camp, and if they do, they must register it under the name of a Lebanese person. They are forbidden from owning a house or land in their name outside the refugee camps.

Before 2001, a Palestinian had the right to own property, was entitled him/her to own land, and was treated like an Arab citizens, but that changed with the issuance of Law No. 296, which amends some sections and articles of the “Law of Acquisition of Real-Estate Rights by Foreigners in Lebanon”.

Suleiman explains that this new law came in relation to “late Prime Minister Rafic Hariri's economic project aimed at increasing foreign investments by providing facilities to purchase real estate, which prompted some Lebanese parties to reject this on the pretext that it encourages the Palestinians to own property. So he decided to deprive those with no country of the claim to ownership. Palestinians, even though they are not explicitly referred to, are the ones intended here under the pretext of combating naturalization [tawteen].”

The aforementioned law states that “No real right of any kind may be acquired by any person that does not carry a citizenship issued by a recognized state, or by any person if such acquisition contradicts with the provisions of the Constitution relating to the prohibition of permanent settlement [Tawteen].” Because of it, a myriad of legal problems arose for many Palestinians who had purchased real estate before the law was issued and they didn’t register them under their real names.

The list of restrictions does not stop here. Suleiman adds that “a Palestinian in Lebanon is subjected to racist practices without a law to govern this, such as his right to move freely, with Lebanese army checkpoints situated at the entrances to most of the camps, while outside the refugee camps, he is subject to security suspicions in accordance with profiling Palestinians. He also does not benefit from the legal aid granted to Lebanese people who are unable to afford the costs of legal assistance, and is subject to a travel ban due to political fluctuations,” as has already been done with a decision issued by the Minister of Interior in 1994 (abolished in 1998) which prevented Palestinians with Lebanese travel documents from returning after the Libyan government terminated their work contracts and expelled them for political reasons. The decision also stipulated the prevention of Palestinian refugees from entering or exiting the Lebanese borders without special permission, even if they were carrying the required travel documents issued by the Lebanese General Security.

Suleiman also mentions the discrimination that is practiced against Palestinian students in universities and institutes that require entrance exams, as “the majority of these institutions do not accept them at all, even if they pass, because of the way Lebanese political parties within them divvy up the student body.”

He also points out that “governmental hospitals do not receive Palestinian patients without a prior contractual agreement with UNRWA, and this rarely happens.”

Weapons in exchange for rights?

Estimates of the total number of Palestinians who fled to Lebanon before 1948 and up to 1950 are between 110 and 130 thousand refugees. Today, the exact number of Palestians in Lebanon is unknown. While “The Palestine Strategic Report” prepared by the “Al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies and Consulations” indicates that the number of Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA at the beginning of 2019 was around 534,000, a report under the name “Population and Housing Census in the Palestinian Camps and Gatherings in Lebanon 2017” suggest other findings. The project, prepared under the helmet of the Lebanese-Palestinian Dialogue Committee (LPDC), in partnership with the Lebanese Central Administration of Statistics (CAS) and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS), has indicated that the number of Palestinian refugees in camps and gatherings has reached about 175,000.

This discrepancy in figures poses multiple problems, especially with the influx of 100,000 Palestinians from Syria after 2011. Around 25,000 of these are still in Lebanon. They have not been able to migrate or return to their camps and homes in Syria, either because they were destroyed or because of legal or security obstacles.

These numbers, distributed among 12 camps and 156 communities in Lebanese regions, made “the environment of the camps an attractive one to lawlessness. In them, weapons and drugs run amok because Lebanese laws do not take into account Palestinian privacy, but rather even encourage its violation,” according to al-Ayyi.

Abdel Hadi ties “the reasons for this security and societal reality in the refugee camps to the high rates of unemployment and poverty of more than 80% of its inhabitants, and the failure of UNRWA to carry out its relief missions and provide services, thus creating an environment that can be breached by drugs and terrorism.”

Therefore, the “Joint Palestinian Action Command”, which includes Palestinian factions and forces with different orientations, has worked to form joint security committees in the refugee camps, all in coordination with the Lebanese security services. Also, “the Palestinians were able to spare the camps any forms of exploitation within Lebanese circles or during the Syrian war, since they are neutral and never interfere in Lebanese affairs,” Abu al-Aradat asserts.

The independent management of Palestinian refugees of their camps date back to 1969 and the Cairo Agreement, which stipulated the establishment of committees to care for the interests of their residents, known as “People’s Committees”. Despite the termination of the aforementioned agreement in 1987, the state of Lebanon hasn’t entered the refugee camps and continues to deal with these committees as a sort of “de facto authorities”.

Abdel Hadi sees that the Lebanese-Palestinian relations are “based on security interactions, nothing more, while the Palestinians want them to be comprehensive. They grew optimistic at the establishment of the Lebanese Palestinian Dialogue Committee and hoped to bypass the strictly security-like interaction and build political and economic relations, but this did not happen.”

On the other hand, al-Ayyi indicates that “the committee is an advisory one, not executive, and is working on a thorny and sensitive issue. It has been able to break the stalemate, work on some laws, and help rebuild the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp,” which was destroyed in the 2007 clashes between the Lebanese army and the Fatah al-Islam organization. It has also been able to “submit projects of development in the refugee camps with funding from institutions and countries that are friendly to Lebanon and Palestine.”

Abu al-Aradat links the establishment of the committee with the “path taken by the Palestinian leadership in 2005 to establish better communication with the Lebanese government, work towards greater openness which led to the ‘Declaration of Palestine in Lebanon’ in 2008, issue a public apology for past mistakes, promise public disclosure and review, and open the Embassy of the State of Palestine in Lebanon, which means that relations have become active between two states.”

Al-Ayyi attributes “the committee’s failure to achieve a major breakthrough to Lebanon’s politically complex conditions following several resignations of successive governments.” He says, “We consider the committee a focal point between Palestine and Lebanon, and we are trying to institutionalize the Palestinian file in the state of Lebanon, but the partisan disputes in Lebanon arre standing in the way, especially since the parties in parliament are split in two directions: the first completely rejects the Palestinians, while the second sympathizes with them but is not ready to put the file on the table for internal reasons.”

For his part, Abdel Hadi criticizes the lack of Palestinian members in the committee, and calls for the establishment of an executive ministry for Palestinian refugees instead of keeping a committee that can only perform advisory action. He sees that “the core basis for the refusal of some Lebanese to grant rights to the Palestinians is sectarian racism, nothing more, with some Lebanese parties explicitly expressing it: ‘Get lost’.”

In 2018, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas said that “Palestinians are under Lebanese law and that there is no problem in handing over the weapons to the state and the army entering the camps.” In al-Ayyi’s opinion, “disarmament or handing over the weapons will help dismantle the issue,” although he agrees with Abu al-Aradat that the rights file is a separate issue from the arms file and they are not linked in any way.

Displacement or resettlement

Ahmad is thinking of immigrating, even if it’s through illegal means, to join his brother Mahmoud, who had entered Germany by “smuggling” himself via Turkey five years ago. He says, “There are no more options but to either slowly die in Lebanon or take risks.”

He points out that “Mahmoud graduated from a private Lebanese university with a degree in business administration, and remained without a job for three years. We collected five thousand dollars for him to immigrate and now he sends us money to support us financially.”

Mahmoud is not the only one who has illegally immigrated. Some have arrived, while others went back. There are no clear numbers on these “migrant birds”, as Abu al-Aradat describes them, but “there are suspicious campaigns organized by hired individuals to push for displacement with the help of some embassies, and this was accompanied by (former US President) Donald Trump’s announcement of the ‘Deal of the Century’.”

In-depth dialogue on the immigration of Palestinian refugees from Lebanon and the impact of their dispersal around the world on the Palestinian cause has never ceased. Abdel Hadi tells of a “plan to displace refugees and resettle the rest by exploiting the current circumstances.” He says, “According to our information, there are countries ready to absorb their numbers, in order to remove them from Palestine, and this coincides with campaigns to cancel the ‘right of return’ and change the status of the refugees.”

The same applies to the notion of having them resettle in Lebanon. It is always present in the Lebanese political discourse that revolves around the danger of demographic change, and in Palestinian discourse that speak of undermining the “right of return”. However, “they are all flimsy excuses for denying refugees their human rights,” according to Suleiman.

In the past two years, the Coronavirus pandemic and the economic crisis plaguing Lebanon have exacerbated the suffering of the refugees. Then the political events that followed the October 2019 uprising hindered all the work on solving the existing problems.

Al-Ayyi points out that “change in the perspective of granting rights to Palestinian refugees requires a moment of internal and external intersection to resolve this chronic issue.”

He holds “the Western countries that aided in the Palestinian plight responsible for their conditions. The same ones are currently refusing to help them in their livelihood crises, as if they are pushing for their dispersal in many different countries through migration and displacement.”

In light of all this, Lebanese and Palestinian political circles do not rule out that the continuation of the Palestinian reality there as it is will lead to a societal implosion. Therefore, al-Ayyi says that “the question of rights is in the interest of the Lebanese more than it is for the Palestinians, because it leads to stabilizing the Palestinian issue and preventing it from imploding”.

As their issues vary and give rise to numerous assessments, Palestinians continue to be viewed as “a card to be played with by foreigners and Arabs”, as Umm Mohammad describes it.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!