It is difficult to imagine that the first Arab-owned coffee shop in Haifa did not open until the late nineties. That was the case of the city prior to the second Palestinian Intifada (or uprising) that generated a social, political, and cultural trend for independence within the Israeli state. I came to Haifa in 2003 and was introduced to the coffeeshop; ‘Fattoush’.

In it, I found my utopic ideals of a “literary” café. It was there that I was introduced to my first book and in it, I read my first dose of poetry. In it, before we were consumed by Facebook, we would meet up in the coffeeshop on Friday afternoons to read weekly journals under one of its many olive trees. It was where we would retire after our political activism and protests, and it was where I was introduced to alternative music and met new friends.

Beyond this story, which resembles that of many Palestinian and Haifa natives in particular, is an impassioned art enthusiast and owner of the largest local musical collection… a travel and memorabilia fanatic by the name of Wadih Shahbarat, who Raseef22 met to discuss his life and coffeeshop Fattoush. The café would expand over the span of two decades to become a vibrant cornerstone of Palestine’s cultural and social scene. I had deepened my knowledge of the place while participating in its cultural projects for a few years, but this meeting delves into Shahbarat, the man behind the phenomenon, and his many dreams.

It is difficult for one to imagine that the first Arab-owned coffeeshop in Haifa, following the Nakba, was only opened in the late 90s.

Dreaming of a Place that Resembles Us

Driven by a simple desire that may seem trivial to some but was essential to Wadih Shahbarat, the coffeeshop was created to fulfill his and his friends’ need for an ‘Arab’ place to meet and feel a belonging to. “The issue isn’t racist. All there is to it was that we used to meet up in Israeli hangouts, the only ones available to us, and listen to the Hebrew music they played, feeling out-of-place while speaking Arabic,” says Wadih, who had then begun pondering about a place where he and his friends would feel comfortable in.

It may seem like such a small dream, but in that moment of time in Haifa, it seemed a risky venture for those around Wadih. He continues, “The only shops back then where local restaurants and diners; Arab bars and coffeeshop culture did not exist in Haifa. Following the Oslo Agreement, we would travel to Ramallah and see its pubs and cafés. I would go to Cairo and feel jealousy over the tourist scene there, where people would trickle in to listen to Fairouz and Um Kalthoum. I thought we should create something without being fearful of our culture. And we should rally everyone around this culture, and not just Arabs.”

Wadih Shahbarat {captured by Hiba Khatba}

Wadih – who back then worked for the ‘al-Itihad’ newspaper, the mouthpiece for the communist party – did not dream of a simple resto-bar, but rather of a vibrant cultural hub that would host galleries and special events, and where guests would be treated to the delicacies of Wadih’s music collection. “Music is an integral part of where one sits. The music consumed in Haifa was commercial and therefore generic. That was when I began listening to music from across the world, discovering its beauty, and falling in love with it. I feel a powerful and intense high when I introduce people to quality music, and they show interest and ask about it,” says Wadih, who set out to achieve his dream despite the fears and apprehension of those around him. He roamed the coffeeshops of Egypt, Jordan. Paris, and London, seeking inspiration and gathering ideas for his project, and began looking for the perfect location.

Designer Wael Wakim and writers Alaa Hlayhel and Hisham Naffaa’ along with calligrapher Ahmad Zo’bi, were all friends of Wadih who helped him find and establish Fattoush on Carmel Avenue, the main street that was appropriated by German settlers in the mid nineteenth century and had a view of the Baha’i temple.

“In the beginning, I looked for a location in the ‘Wadi Salib’ ( or Valley of the Cross) neighborhood, but the story of how Palestinians were evicted and expelled from it made the idea of opening a coffeeshop there displeasing. One day, as we were walking through Carmel Avenue, we saw the place. It resembled a rundown warehouse, but I was immediately enchanted by the room with the ribbed vault (an architectural feature of ancient Palestine during the Ottoman era),” which would later become the “Arabic Room”; the prized jewel of Fattoush. In 1998, the coffeeshop was built and was named “Fattoush” by Wadih’s friend Wael – a name that quickly grew on Wadih. “The beginning was a real challenge. All I had was a suitcase of music and a bunch of money that I wanted to challenge the project’s naysayers with and those who said people only hang out in Israeli shops.”

“We used to meet up in Israeli hangouts, the only ones available to us, and listen to the Hebrew music they played, feeling out-of-place while speaking Arabic.”

Coffeeshop and restaurant Fattoush {captured by Hiba Khataba}

A Witness to Social and Political Upheavals

The beginning was not easy, not only because of the aforementioned reasons, but also due to social factors that prevented factions of the community from accepting the creation of a new Arab space open to the possibility of a ‘night life’. Despite the successful grand opening, “Droves of people participated in the grand opening. Amal Morcos sang and writer Salman al-Natour delivered an impassioned speech about the birth of a cultural hub in the city, and that culture starts from coffeeshops,” says Wadih, “But the project quickly took a small downturn. Seedy individuals came to the place and took the novel sight of Arab female waitresses as an open invitation to hit on them. But the girls were very sagacious and knew they were breaking societal and parental norms with their work.” Wadih recalls a particularly gruesome incident, in which one of the café’s female employees – a waitress studying and living in Haifa – was murdered under the suspicion of being a “prostitute.”

Wadih recalls the gruesome murder of one of the coffeeshop’s female employees who, as a waitress living and studying in Haifa, was considered a “prostitute.”

“We understood the reason behind the place’s decline: people’s mentality. Later, some friends like Maria De Pinha, Kholoud Badawi, and Palestine Ismael decided to frequent the place regularly. Some worked as hosts and stewards, and things began to change. But the major shift was with the start of the Second Intifada or the events of October 2000,” says Wadih. Around that time, Arabs began frequenting Arab-owned spaces due to the tense political situation, and people visited Fattoush in drones. “Those who used to hang out in Jewish pubs found a refuge. And I took advantage of the situation to improve the place until it gained special prominence with its frequenters, both within the country and outside, in the coffeeshop’s fourth and fifth years. We hosted cultural nights; I gathered and implemented ideas from friends,” explains Wadih. At this stage, Fattoush became a public sphere for convening and articulating social, political, and cultural discussions about the community. As the older generations would gather around their bonfires to weave their people’s stories, the younger one would gather in coffeeshops to write their own stories. “People found the café fertile ground for meeting, starting projects and bands, as well as dating; many of those who met in Fattoush went on to get married. Back then, people felt there was a place in Haifa they could feel proud of… a place they felt their own,” assures Wadih, who became a patron of local arts and culture projects in Haifa both to support them and promote his café. He adds, “Later, customers of Fattoush opened new coffeeshops inside and outside Haifa. I remember a coffeeshop before Fattoush, the Zaytouneh café in Nazareth, which was shut down because of Islamists.”

A performance by Akram Abdulfattah and Samah Mustafa in Fattoush bar {captured by Wael Abu Jabal}

Music Collector And Rapper Of Peoples' Gates

One cannot separate the experience of visiting Fattoush from the music that would be heard there. Wadih is biased towards eclectic music genres that he collected over several years from different cultures. “I can talk about two distinct musical periods; in the first, I listened to pop and songs popular on MTV. When I was around 15 years old, I moved from my boarding school in Jerusalem to work as a reporter for the Itihad newspaper in Haifa, where I joined the ranks of the communist youth. My friend Wael gifted me an album for Armenian jazz group Night Ark, and I fell in love with the fusion of Oriental and Western. I started visiting the music shop every day, and I was introduced to the Oriental jazz of Rabih Abu Khalil and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. It became a hobby of mine to discover new music from across the globe and save up the money to buy the records. Later, when I was 19, I took up music history in Haifa University while also studying graphic design.”

Wadih can break down the geographic origin and composition of a piece of music just by listening to it. He travelled to Spain, France, Istanbul, Egypt, London, and Berlin, where he became known among music shop owners and collected a great deal of musical gems that visitors of Fattoush got to experience and hear. “I think Fattoush became a house for music. I remember some genres were a little tricky for people to hear, but eventually they accepted the music as an indivisible part of the experience. I consider my travels to be ‘musical tourism,’ and I derive joy from bringing music back to share a personal joy with people,” he says.

Many visit Fattoush and wonder who designed the place. Wadih has an eye for décor and interior design for the space around him. He decorated every nook and cranny of the coffeeshop and later the Fattoush bar and gallery with his style. He doesn’t distinguish between music and the material world of interior design. Speaking to me on the topic, he says, “When I first started Fattoush, I considered Oriental and Palestinian décor in particular, but I quickly decided on fusing different cultures. The place has an Arabic tint, but it also makes room for other cultures.” He adds, “Music was my entry point to figuring out how to furnish Fattoush. While searching for music and looking at different album covers, I was introduced to this world. I collected pieces from the markets I visited in my travels to Egypt, Turkey, Morocco, and France.”

Fairouz chamber in Fattoush coffeeshop and restaurant {captured by Hiba Khataba}

A Safe Space for the Queer Community

Fattoush is known for being a safe haven for queer men and women. When Wadih came out as gay, the shop became a welcoming space for the LGBTQ+ community. “A friend placed Fattoush on a tourist guide list of queer-friendly spots in the city. This attracted new groups and categories to the coffeeshop. We were also clear with our waiters and waitresses (from the get-go) that all people are welcome, and there was no room for any form of discrimination or harassment. That made a huge impact on the mindsets of those who came to work for Fattoush, especially withing the younger age groups.” Wadih recalls an incident in which a religious Arab family visited Fattoush and sat next to a table that had a group of young gay men. When a man from the family requested the group to be kicked out in order for the family to remain seated, the waitress reacted impulsively and ripped the family’s order, asking for them to politely leave. The young group in question then mentioned feeling safe in Fattoush. During the last decade, Haifa witnessed a revival of public spaces that worked in tandem with organized civil rights movements to create a safe and visible space for queer people.

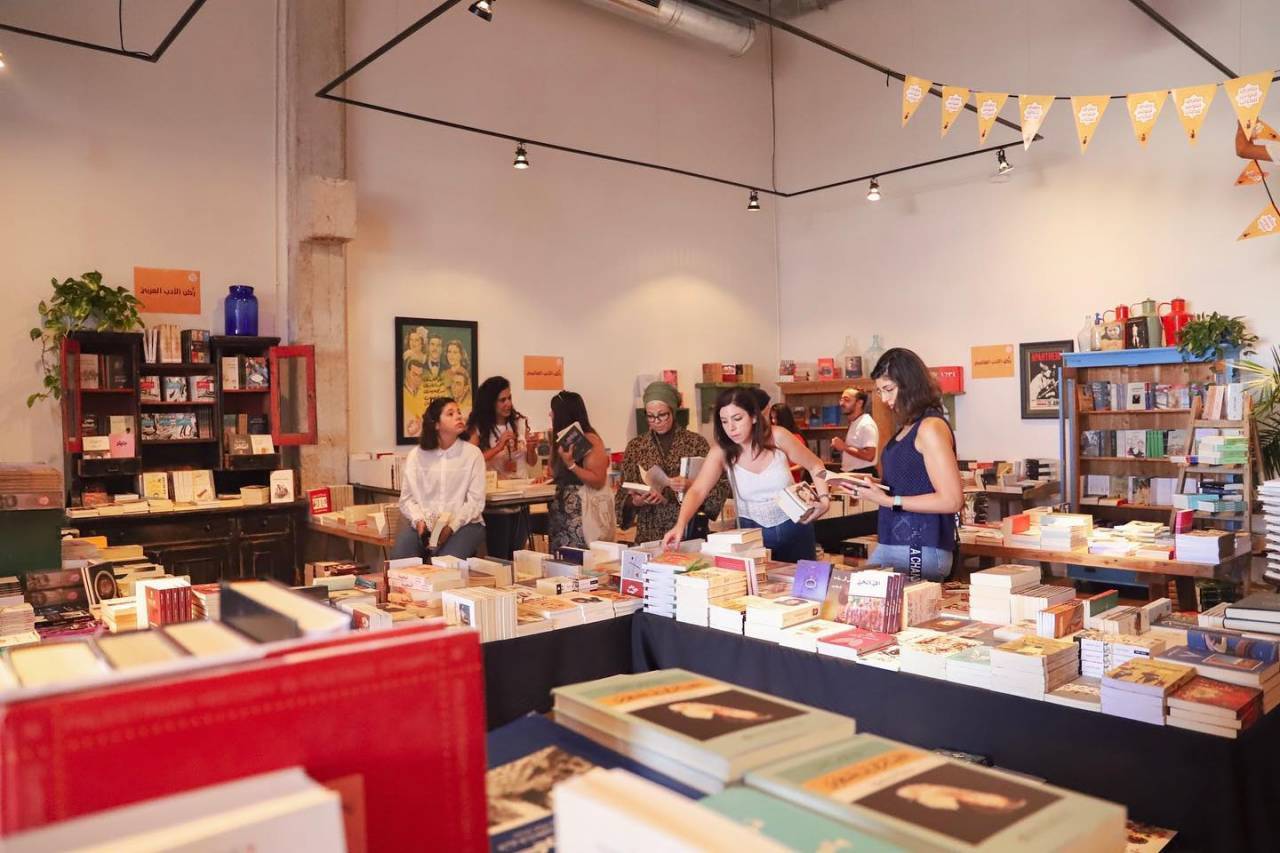

Fattoush Book Fair {captured by Hiba Khataba}

Successive Dreams: The Store, The Bar, And The Gallery

Wadih quickly tires of routine and exorcises his restlessness in small things like moving around the furniture, as well as in large projects, like starting cultural projects and endeavors. From the year of 2016, Fattoush began to systematically sponsor cultural projects. The Fattoush store for books, arts, and music was first established in sync with expanding to an additional floor. It housed 4 small and intimate seating areas named ‘Grandpa’s Room,’ ‘Grandma’s Room,’ the ‘Fairouz room,’ and the ‘Karaoke Tribute room’ – each one with its own unique décor and vibe. The Fattoush bookstore offered books from the Arab World, as well as music records and local, handmade trinkets. An annual book fair that resembled a ‘reading and literature’ festival was also launched, and everything from literary and intellectual evenings to small art galleries were organized. These started with the establishment if Fattoush as the first Palestinian space for performance in the city. Hundreds of artists held galleries – some their very first – in the place. But did Wadih tire of the routine again? “The first cultural activities that accompanied Fattoush were the galleries, but the gallery area in the coffeeshop and restaurant was small. I dreamt of a spacious gallery area that was suitable for large displays. I dreamt of a stage for large productions and a stunning bar. That was where the idea for a bar and gallery was born,” says Wadih, who found the perfect spot for his dream project in 2018.

I see Haifa from two viewpoints; the modern gate and the ancient gate that stopped with the Nakba and halts at the Palestinian flags that made the city. I can’t stop traveling between the two gates, and I can’t see one side of Haifa without the other.

“I felt like people were waiting for a project like this. They were hungry for a place to meet and hang out in during the weekends. The space, with its gigantic surface area and high-caliber design, made its visitors feel like they were out of town.” The space was launched in the fall of 2019 in the lower part of Haifa (the historical hub and center). A bar with contents from different corners of the world – a high ceiling from which hangs the lighting pieces that once lit an old ship or train, and seats from Europe during the beginning of the last century – pieces that merge between the industrial and the classic. Such antiquities aren’t situated to far from a large platform that receives live music and DJ performances. Next to it is the large Fattoush Gallery meant to host and produce art exhibitions. Wadih says, “The beauty in the available space is that it is flexible and can accommodate any form of performance, so we were able to organize loud and deafening nights but also other quieter nights of classical music and hip-hop. We organized markets for handmade products. We hosted the ‘Khashaba’ theater in ‘cabaret’ performances (displaying the type of work in a place that harmonizes with it), fashion shows, as well as the Fattoush Book Fair.” This trip has ended, but only temporarily, due to the Coronavirus, which forced him to close the cafe, bar and gallery until further notice.

‘The 9:30 Water’ Display in Gallery Fattoush

Capital And Culture

Fattoush operated according to a model that helps fund cultural projects. Palestinian (artists) within the territories endure tough economic conditions because they don’t receive financial support from Palestinians, and most of them don’t want Israeli support. Concerning this cultural model, Wadih explains, “I believe that money and capital can support culture. But we have ventured into a huge project – the bar and gallery – which put a strain on our financial situation. Visual arts and the gallery require huge budgets. The gallery is currently closed until we find a way to run it. Following the pandemic, we will further develop and expand the project, recuperating the brand name that Fattoush made for itself.”

“I believe that money and capital can support culture.”

Regarding the type of culture Fattoush aspires to present, Wadih says, “Fattoush’s identity is fluid. It is a space for free art, queer people, leftists, and others. This fluidity is reflected in its frequenters; you can find the bourgeoisie crowds, the students, the workers, the families, and the tourists.” He adds, “People may be surprised by what Fattoush offers, and some might not like it. But I make choices according to my personal tastes and what serves a certain cause or emancipatory idea for society. In everything we offer, I am adamant about the show’s accompanying sensual, auditory, and visual experiences.” The book fair, for instance, is not a simple pile of books, rather, it is a visual feast of décor and color design with an auditory companion of music. Wadih does not consider the shop’s identity to be strictly ‘Haifa-n’. He explains, “Despite the human melting pot present in Haifa, I feel as though it is divided ethnically and by class. I see Haifa from two viewpoints; the modern gate and the ancient gate that stopped with the Nakba and halts at the Palestinian flags that made the city. I can’t stop traveling between the two gates, and I can’t see one side of Haifa without the other. Haifa changed, as did the world. Unprogressive people live among us, but I feel there is tangible societal progress, and that I am one of these things accompanying that evolution.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!