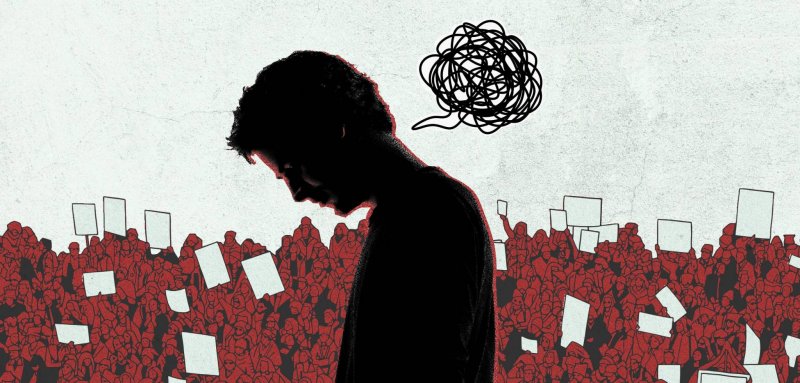

The reemergence of protests in Beirut has demonstrated that the revolution is not going away any time soon. Masses of protestors flooded the streets, rioters destroyed and tagged banks and the state once again portrayed its inherently violent nature. To some, this week of rage is seen as a ‘revival’ of the revolution, prior to which many commented that the revolution had been dying, citing the lack of street activity. To measure the strength of the revolution by street activity alone can be an inaccurate metric, mostly because it ignores revolutionaries that experience difficulties going down.

The revolution may have given us hope, but depression is the enemy of hope.

A recent essay in the LA Review of Books introduced me to a seminal phrase in Johanna Hedva’s ‘Sick Woman Theory’: “How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?” Similar to what the author of the former expressed, this sentence captures something I’ve been struggling with for years now but much more acutely since our uprising began. I realize that it opens up a crucial discussion that needs to be had. How can I, for instance, block a road at sunrise if I can’t even get up in the morning? How can I stand in front of fully armed riot police if the sight of a wooden spoon still makes me shudder? How can I answer the calls of “yille we2if 3l balkon” if I can’t even answer the phone?

Before the events of October 17, a collective sense of despair hung in the air across Lebanon. The revolution provided a glimmer of hope in an otherwise bleak outlook. It was a moment of collective awakening. Being out on the streets and yelling sentiments only ever kept amongst friends felt like an emancipatory act. Street protests are vital to any social movement for a myriad of reasons and especially in Lebanon where we see a newfound national unity being formed on the streets. As important and satisfying as street protests are, to some participating in them is not an easy task.

Being depressed in a revolution means feeling despair when people around me are elated, it means constantly calculating the impact events I partake in will have on me or it can simply mean lying in bed feeling worthless and unable to overthrow the system

Those of us living with mental illnesses can find leaving our apartments difficult, let alone venturing out onto the streets. Social anxiety can make even a cafe's atmosphere too anxiety inducing, let alone a riot. Living with depression and/or anxiety can make a person feel removed from society, but that does not mean that they can’t participate in revolution.

Discussions of mental illnesses in our movement has been sparse, and still a bit of a taboo in our society; perhaps it’s another one of those red lines that we should be crossing. This article isn’t an attempt to definitively describe the mentally ill revolutionary’s experience, or discount the value of street protests, instead it is an attempt at sharing a conflicted personal experience in hopes of reaching out to those with similar struggles. I’m constantly reminded of the woman holding a banner that read “these are the happiest depressed people I’ve ever seen” or the graffiti that read “down with anxiety”. I know other people are experiencing these issues but have few outlets to discuss them, which compounds the feelings of loneliness and isolation.

The revolution may have given us hope, but depression is the enemy of hope. Being depressed during revolution means feeling despair even when people around me are elated, it means selectively choosing what street actions to take part in if any, it means constantly calculating the impact the events I partake in will have on me (if it’s worth the psychological toll), or it can simply mean lying in bed feeling worthless and unable to overthrow the systems that I feel put me there in the first place. It means needing extra care and feeling like a burden to my friends. In short, it’s a feeling of irrelevance at best, and a hindrance at worst.

Public gatherings can be emotionally taxing. The feeling of being trapped in a crowd, the eye-clinching sounds of metal banging, the fear that at any moment the sadistic riot police will charge at us, barking and smacking at random. There’s nothing scarier to me than the stampede that follows. Even watching these images on T.V or social media can at times make me sink deeper into despair. The scare-tactics of the state (the presence of heavy machinery, assault rifles and even RPGs) have a disproportionate impact on me. There’s a constant paranoid fear that one of these events will push me over the edge and result in irrevocable psychological damage.

Calls to help block roads sends waves of guilt and shame through my body. Guilt because I know it needs to be done, shame because I know I can’t do it. When I can muster up the emotional and physical energy to go out on to the streets, I do, but it’s rarely easy and usually takes a few days to recover.

There’s a certain obligation I feel, as someone who supports the revolution, to be with my fellow revolutionaries on the streets. I often would go down but live to regret it. Even though I had felt terribly uncomfortable, I remained anyway, thinking that I was doing my part for the revolution. This exposes a different problem, one rooted in the discourse around the revolution, particularly the equating of protests and revolution.

The success and health of the revolution shouldnt be measured by the amount of street actions alone and our tendency to do so often obscures and marginalizes the revolutionaries that can’t participate in those activities. It is almost to say that if you aren’t on the streets you aren’t partaking in revolution. This is blatantly false. The discourse on what constitutes a revolutionary act should be expanded to better integrate those that can’t go down and widen our perspective of what constitutes a revolutionary act.

While attempting to destroy the old order, we will also need to conceive the new. This requires organizing, discussing, theorizing, all of which aim towards the same revolutionary goals. Much of these activities have already been taking place since the very beginning. They don’t take place in the streets, but rather in the workplace, in houses, cafes, public squares, over the internet. Organizing communities, mutual aid networks, unionizing workers, community care, art, fostering new conversations; all these things can serve transformative purposes, creating new ways of relating to one another and developing new societies. Especially in the case of Lebanon, where the power structures are so entrenched and convoluted, what is needed more than ever is a new imagination.

Throwing bricks at banks is not the only place revolutionary activity takes place. Understanding that reframes such actions from obligation to choice; it’s not the only option laid out for potential revolutionaries. Reframing the way we see revolution opens up new fundamental questions, the answers to which can help provide new metrics to perceive revolutionary progress.

For instance, are the new forms of solidarity we see developing not a revolutionary break from the prevailing competitive capitalist dynamics? What about the new national conceptions of identity that have been forming, aren’t these a revolutionary break from sectarianism? Even the hope that has broken out across the country can be seen a revolution against the abysmal national nihilism that we know all too well. These may not be as obvious and apparent as street protests, they can’t be filmed or televised, but surely these constitute a revolution in progress as well.

Under the rule of men who prefer us miserable and isolated, maintaining a semblance of hope is a revolutionary act, a middle finger to those that depress us and keep us in bed

In creating a new metric, perhaps the first place to look is at the root problems plaguing our nation: sectarianism, clientelism, corruption, capitalism, stratification, racism, sexism… too many isms to count. If a revolution can be considered as an overthrowal of oppressive structures, then surely the metric should be the negation of these powers (or the inverse, the power these forces, and their agents, still have over us and our society). Of course some of it becomes a bit abstract, especially when dealing with super-structures like capitalism or racism.

In these cases, revolutions can be both on the streets and within one’s self.

In these cases, revolutions can be both on the streets and within one’s self. After all, can any of us say we have not internalized at least some of these isms? Wouldn’t rooting them out of ourselves in these times not constitute a revolutionary act? If we’re to tackle such complex and intangible concepts, surely starting with ourselves is a necessary first step. Any act that negates their power over us is a revolutionary act. If this is the case, than self-care itself can be considered revolutionary, refusing to succumb to the divisive and oppressive demands of the ruling class or refusing to be an agent of their power. Under the rule of men who would prefer us miserable and isolated, maintaining a semblance of hope is a revolutionary act, a middle finger to those that depress us and keep us in bed.

Acknowledging the different forms revolutionary progress can take will open up new discussions. It will alleviate the guilt some of us feel for being unable to participate in actions we support while also providing new avenues to perceive revolutionary progress. It is all to say: If you’re uncomfortable in loud, crowded, potentially confrontation spaces, that's okay, there are other ways you can further social and political change. Convincing your racist uncle that Palestinians do not commit 50% of the petty crime in Lebanon can be a start, providing physical, emotional or financial support to others is another, or it can even be realizing that you still sort of believe in the free market and are attempting to cure yourself of that unfortunate belief. What’s important is that this progress is being made, progress that is not factored in to popular conception of revolution. The next time someone says the revolution is dying, perhaps it says less about the revolution, and more about where they’re looking.

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!