*This investigation was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

This investigation traces—through documents, testimonies, and international trade routes—how Yemen’s sardine reserves were transformed into a source of profit for cross-border corporate networks and spheres of influence. More importantly, it points to how volatile government decisions paved the way for an illegal and destructive industry that has depleted one of Yemen’s most vital marine resources and irrevocably altered the lives of coastal communities forever.

Fisherman Mohammed Nasser returned from the sea as he does every day, but this time without a single sardine. He pauses on the shore for a moment before hauling in his empty net, as if searching its knots for an explanation of how the sea has turned against him.

The sea that once provided Mohammed with enough to support his family of five has, in recent years, become a vast expanse of mounting losses—trips in which he sets out in debt and returns with fresh disappointment, his hope diminishing with every delay of the sardine season that fishermen had been relying on to pay off the debts of a harsh year gone by.

Mohammed tells Raseef22 that the sea has changed significantly. He once returned with abundant quantities of sardines, but now, on most days, he comes back without a single fish to feed his family.

Mohammed is not an isolated case. There are thousands of fishermen like him along Yemen’s nearly 2,500-kilometer coastline. The governorates of Hadramawt and Al-Mahrah alone produce around 60% of Yemen’s fish, and approximately 667,000 people depend on this sector for their livelihoods.

Yet this coastal strip, long the economic backbone of coastal communities, has witnessed an unprecedented decline in fish stocks over the past five years. While climate change stands out as a key environmental factor threatening the sustainability of marine resources, mounting evidence and converging reports point to another central cause that deepens the crisis and recurs in every account: fish-grinding factories that appeared suddenly and began consuming vast quantities of fresh fish instead of processing only waste. These factories have become a primary driver of the sea’s depletion and the impoverishment of the communities that have depended on it for centuries.

From sea to factory: Preparing the fish

After years of declining catches, fishermen began linking the disappearance of sardines from their nets to the rapid expansion of fish grinding factories that have appeared in Al-Mahrah and Hadramawt over the past five years.

These factories, which were supposed to rely solely on grinding fish waste, have gradually become major consumers of fresh fish, grinding more than a third of total production, especially sardines. This shift has diverted fish from a vital food source for Yemenis to a raw material ground and exported abroad, generating millions of dollars that do not even reach the state treasury.

After years of declining catches, fishermen began linking the disappearance of sardines from their nets to the rapid expansion of fish grinding factories that have appeared in Al-Mahrah and Hadramawt over the past five years. An investigative report reveals how Yemen’s sardine reserves were transformed into a source of profit for cross-border corporate networks and spheres of influence.

In the absence of oversight, weak enforcement of laws, and the broader state of confusion gripping the country, conditions that the grinding factories have exploited, this investigation uncovers how local and foreign investors seized an open opportunity for quick profit, while local fishermen faced a steadily impoverished sea and a sardine season cut short before it even began.

From this transformation, our investigative journey began along the eastern coastline, from Hadramawt to the edges of Al-Mahrah on the Omani border. Over eight months, we sought evidence explaining the disappearance of large quantities of fish and how they were turned into powder and oil that leave the country in trucks loaded with millions of kilograms of high-value product.

Along the way, the author documented testimonies from local fishermen, officials, and experts. We also reviewed specialized reports on the marine environment and obtained official documents and investment permits that reveal the scale of violations committed by the grinding factories and how their unregulated expansion has disrupted the marine life cycle, diverted fish stocks away from fishermen who depended on them for generations, and threatened both the marine environment and human lives.

As we tracked fishing operations along the coast, early signs began to point to the heart of the problem. Small boats that once returned laden with sardines during the season are now forced to sail farther and into deeper waters in search of meager quantities that barely cover the cost of the trip.

At the same time, we observed intensive activity from larger boats unloading their catches outside official landing centers. Local fishermen reported that these operations peak under the cover of darkness, with shipments transported in specially equipped vehicles toward grinding factories during the night or just before dawn.

Although testimonies confirmed that activity peaks at night, the investigation’s camera documented these operations continuing in broad daylight (around 10:20 a.m.), reflecting a clear sense of confidence born of the absence of any legal accountability or repercussions.

A video clip of fishing boats unloading their catch outside official landing centers and the transport of their catches to grinding factories.

These field observations were the first to confirm that the decline in catches was not a natural phenomenon, but rather the direct result of increasing demand from factories that have become fierce competitors to fishermen for the same fish stocks.

Factories operating outside their limits

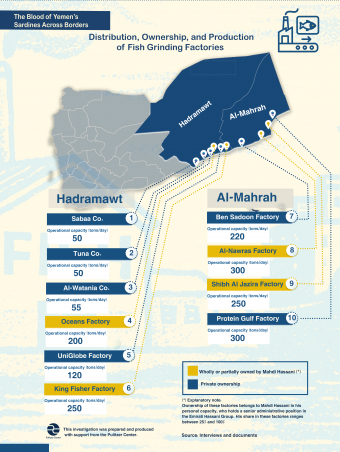

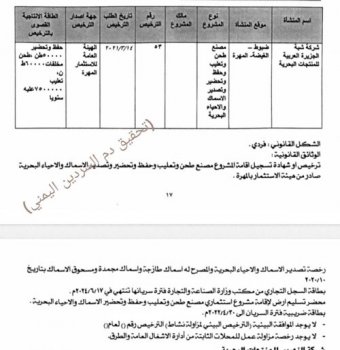

Five years ago, new facilities appeared along the coastal strip between Hadramawt and Al-Mahrah with investment licenses for integrated fisheries projects that were supposed to be limited to processing and canning, with small units for grinding waste. However, these factories, 10 in total, have turned into mills that receive fresh fish directly from boats.

As for the three factories that operate in processing and canning, they have expanded their grinding units to the point that they now rely on fresh catch, in violation of the terms of the official license, which explicitly stipulates the grinding of “fish waste.” A ministerial committee report also concluded that these factories are exceeding the specified production capacity.

Documents and interviews show that ownership of these factories is divided among an Emirati owner and foreign and Yemeni investors, and that their expansion has created a daily demand estimated at 1,600 tons of fish, with a total annual production capacity of more than 535,000 tons, which is double the country’s annual national production. This demand has encouraged the trade in small fish and pushed fishermen, under the pressure of need, toward overfishing, especially since the factories purchase any quantity at a fixed price (500,000 Yemeni riyals per ton, about $300), without regard for seasons, species, size, or environmental impacts.

Source: Report of the ministerial committee tasked by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries to inspect grinding factories in Hadramawt and Al-Mahrah during 2024.

Although investment licenses require factories to grind only fish sorting and processing waste, documents and field observations reveal activity that falls outside all regulations. These facilities do not have integrated production lines or adequate refrigeration or cooling systems, even though each factory consumes between 50 and 300 tons daily.

Despite the scale of the violations, no notable penalties have been recorded against offending fishermen, and decisions to shut down noncompliant factories were issued and briefly implemented before being reversed, according to official sources. This indicates a wide gap between regulatory texts and reality, along with an almost total absence of oversight over a marine resource that serves as a lifeline for thousands of coastal families.

Testimonies and evidence from the field

Fishermen confirmed to us that quantities of fresh fish are being unloaded directly inside grinding factories. Ahmed Abdullah Baser, a fisherman and head of the Al-Hasi Fisheries Association in Hadramawt, says: “Thirty trawlers are operating with 24 or 30 thousand fishermen who trawl small fish because trawling continues and the grinding factories are running. The first grinding factories were meant for leftover fish from catches destined for canning, but then the tampering started. Any catch they get from the sea is taken straight to the grinding factory.” He adds, “Now the catch is lighter. It no longer brings in what it used to. You go out and barely bring back anything.”

Ayyoub Hammoud, a monitoring officer at fish landing sites in the Muhayfif area of Al-Mahrah governorate, notes: “We see boats trawling every day, collecting all the creatures in the sea, even fish eggs. That is why when fishermen try to fish, they find nothing.”

Our interviews with managers of several of these factories, including Jasweer Mohammed (an Indian national and manager of the Gulf Protein factory), Mahdi Hassani (an Emirati national and manager of the Emirati Hassani Group of Companies, which partially or fully owns four grinding factories in Hadramawt and Al-Mahrah out of a total of ten), and Talal Al-Menhali, deputy executive director of the King Fisher factory, reveal that their facilities rely on fresh fish in massive daily quantities, reaching up to 400 tons in some factories. According to marine environment experts, this exceeds the sea’s natural production capacity and threatens the sustainability of fish resources.

The factory managers state, in separate interviews, that they obtain fresh fish delivered to their gates through suppliers using large trucks or directly from fishermen, provided the quantities are substantial. They note that the fish comes from various Yemeni coastal governorates.

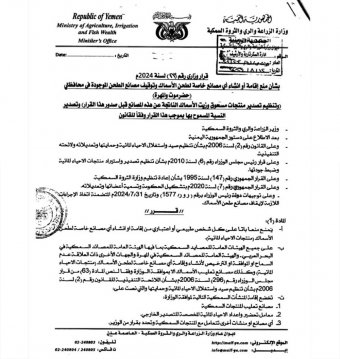

The investigation’s author obtained investment licenses for grinding factories, as well as a report by a ministerial committee commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Fisheries. The committee conducted field inspections in 2024 that included visits to ten factories in Hadramawt and Al-Mahrah.

The report reveals that grinding factories are using fresh fish instead of waste, contrary to the conditions of their licenses. Fisheries companies grind only about 30 percent waste compared to 70 percent fresh fish.

Despite the committee’s findings, which fully align with what this investigation uncovered regarding licensing violations, the responsible authorities have not taken measures to halt these abuses or hold those responsible accountable. Instead, they have helped enable the continuation of these violations by facilitating the export of the factories’ products abroad.

‘Overfishing’ and rising exports

This rapid expansion in the activity of grinding factories has led to an outcome that has become clear to both fishermen and experts: a decline in the presence of sardines and small fish species that form the primary food source for larger fish such as tuna. Sabri Lajarb, Director General of the Marine Science and Biological Research Authority, Hadramawt Branch, explains that the expansion of grinding factories over the past five years has become one of the main drivers of overfishing, resulting in a dangerous depletion of fish stocks and a serious threat to the sustainability of marine resources.

Lajarb adds that the fishing methods used, including gillnetting, purse seining, trawling, blasting, and the use of shartwan and sakhawi nets, traps, oxygen, and intense nighttime lighting, destroy coral reefs and natural habitats. These practices also drive fish to migrate, disrupt ecological balance, and make traditional fishing increasingly difficult.

Official documents, statistics, and licenses reveal that these factories generate massive quantities of fishmeal and fish oil that are exported abroad with facilitation by the General Authority for Fisheries in Al-Mahrah.

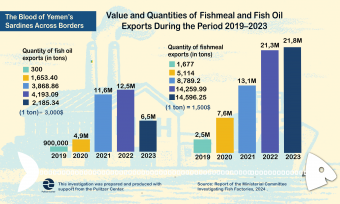

According to the official documents we obtained, published here for the first time, fishmeal exports between 2019 and 2023 reached approximately 44.4 thousand tons, with a value of 66.6 million dollars, calculated at 1,500 dollars per ton of fishmeal.

Fish oil exports between 2019 and 2023 amounted to approximately 12.2 thousand tons, with a value of 36.6 million dollars, calculated at 3,000 dollars per ton of fish oil.

The documents indicate that rising demand for fresh fish has pushed fishermen into intense competition and led to a doubling of trawling and indiscriminate fishing practices, placing direct pressure on fish resources and threatening the primary sources of income for thousands of coastal families.

Report on sardine fishing in Hadramawt

Along the coastline between Al-Mahrah and Hadramawt, we identified ten companies, including seven main fish-grinding factories, operating on a near-daily basis to convert large quantities of sardines and other fish into fishmeal and oil for export.

Attempts to gain access to these factories were difficult at first, as those in charge insisted they were dedicated solely to grinding fish waste, which made entry more complicated. However, the investigation’s author eventually managed to enter some of them, observe the grinding mechanisms, oil tanks, and production units, document the names of investors, follow export operations through the Shahn land border crossing linking Yemen and the Sultanate of Oman, and record environmental violations inside the factories and in the surrounding areas.

The strong smell of fish around one of the factories reached us before we arrived. The factory is located on the wide Al-Ghaydah coast in an area otherwise free of noise and residents, except for the grinding facility, which disrupts the coastal calm.

Outside the factory’s perimeter wall, which covers roughly two square kilometers, makeshift ponds have been placed directly on the shoreline. These exposed ponds are filled with wastewater. Their color now resembles the blue of seawater, except that instead of reflecting purity, it reveals the pollution that has tainted it.

Direct inspection revealed that these facilities—operating under the label of fish packaging and canning factories with waste-grinding units—are in fact grinding fresh fish in violation of licenses issued by the General Investment Authority. It also shows that a number of them have exceeded their licensed production capacity, with some operating around the clock, relying on foreign and local labor, amid a clear absence of environmental oversight and weak monitoring of illegal activities that contribute to the rapid depletion of fish stocks, thereby depriving fishermen of their main source of livelihood, and polluting the surrounding environment.

The trail of blood across borders

Some grinding factory owners indicated that ownership is shared between Yemenis and foreigners, while their large volumes of fishmeal and fish oil are exported to two recipient companies in the Sultanate of Oman, according to multiple export documents we obtained. This raises questions about the true ownership network behind the grinding factories in eastern Yemen.

During the investigation and in tracing the flow of fish across borders, we found a small clue in an official document within the minutes of the ministerial committee. It stated that the owner of all grinding factories in Al-Mahrah and Hadramawt is a single individual named Mahdi Hassani, without providing further details. Gradually, the ownership structure became clearer.

Through digital and field research and a series of coordinated contacts, we located the person named Mahdi Hassani, an Emirati investor managing a large company registered in the United Arab Emirates. Open-source research revealed that Hassani is the Executive Director of the Manufacturing Division at the Hassani Group of Companies, Chairman of the Board of Dhofar Fisheries and Food Industries Co, which operates under the Hassani Group, and owner of 50 percent of Alloha Marine Products and Trading. Both Dhofar and Alloha are registered in Oman. Export documents show that these two companies are among the recipients of fishmeal and fish oil shipped from Yemen to Oman through the Shahn land crossing.

A small lead pointed us to a person who owns a “significant stake” in the grinding factories in Al-Mahrah and Hadramawt that threaten the sustainability of Yemen’s marine wealth: Emirati investor Mahdi Hassani. Who is he, and how does his control over this share of grinding-factory production affect local investment in the sector?

We then contacted Mahdi Hassani directly through a recorded phone interview arranged by the owner of one of his grinding factories in Yemen. During the interview, Hassani revealed significant details about factory ownership and production, arguing that the purpose of the grinding factories is not to waste fish but to produce fishmeal used globally in feed and food industries, where demand is high.

Hassani confirmed that he owns four grinding factories in Yemen: King Fisher Factory and Oceans Factory in Hadramawt, and Shibh Al Jazira Factory and Al-Nawras Factory in Al-Mahrah. These facilities were established between 2020 and 2023. He owns Oceans Factory outright, and holds shares ranging from 25 to 40 percent in the other factories, with Yemeni and Indian partners owning smaller stakes. According to Hassani, the factories produce about eight thousand tons annually of fishmeal and fish oil.

However, according to the ministerial committee report, none of these factories, including those fully owned by Hassani such as Oceans Factory, were registered in his name. All were registered under the names of Yemenis listed as the official owners.

Documents regarding grinding factories

Threatening local investment with an unstoppable monopoly

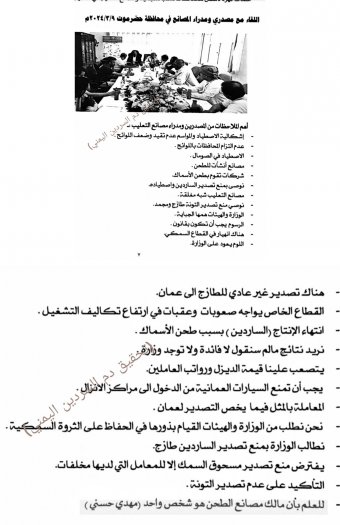

Local fishermen and small fish-food producers in Hadramawt reported losing market share because of the extensive supply and collection network operated by grinding factories and their pricing strategies.

In this context, Mahdi Hassani’s acquisition of the largest share of grinding factories (4 out of 10) stands out. It has disrupted the fisheries sector, harmed local fish-food producers, and contributed to the decline of local fish-canning factories.

In a meeting that brought together exporters and managers of fish-canning factories in Hadramawt with the ministerial committee in Al Mukalla to seek redress and restore their economic activity, participants said the canning factories were “nearly closed.” They warned of the “collapse” of the fisheries sector and the “end of production of sardines because of fish grinding.”

According to the meeting minutes, of which we obtained a copy, they said the Ministry of Fisheries and its affiliated bodies are primarily concerned with collecting revenue. They also noted that the private sector struggles to secure fuel to operate their companies because economic feasibility has collapsed as large quantities of fish continue to be diverted to grinding.

From this, it is clear that violations are occurring and that there is a significant gap between official licensing and actual activity. High profits and financial gain appear to be the main drivers, and cooperation from official bodies has enabled grinding factories to exceed legal limits.

The gap between on-the-ground realities and the official records of grinding factories also indicates a lack of government oversight and the leniency and cooperation of government agencies with clear violations. This forms the core of this investigative report, which aims to understand the dynamics of the fish-grinding industry in the region and its economic and environmental impact.

Fish grinding’s long-lasting environmental impact

Scientific studies and reports indicate that Yemen’s nearly 2,500-kilometer coastline along the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea provides a unique habitat for Indo-Pacific and endemic species, giving it high environmental value. With the rapid expansion of fish-grinding factories in recent years, these facilities have become a main driver of overfishing in the region, according to analysis by Sabri Lajrab, Director General of the Marine Science and Biological Research Authority, Hadramawt Branch.

Lajrab explains that the intensive use of fresh fish by grinding factories, combined with widespread trawling, is depleting fish stocks. He adds that the factories indirectly push fishermen to use indiscriminate, dangerous tools that violate traditional fishing laws, including industrial fishing gear in near-shore areas, which threatens the marine environment with desertification and destruction.

He notes that trawling boats equipped with engines exceeding 200 horsepower and fine-mesh nets enter seabed areas where shrimp and bottom-dwelling fish gather, causing widespread destruction of sensitive ecosystems in Al-Mahrah and Al Shihr in Hadramawt.

According to the minutes of the ministerial committee, the daily production required to meet the needs of grinding factories has reached 1,600 tons. Over nine months, this amounts to a minimum of 400,000 tons from this resource alone.

Environmental researcher Sabri Lajrab says, “We know the stock is declining. When we take samples, we find small sizes. These are not the commercial sizes that should be fished. These small fish are a generation that should remain in the sea to reproduce and maintain the stock.”

Official documents we obtained confirm Lajrab’s account. While grinding factories tell authorities they rely on fish waste rather than fresh fish, the documents show that fish-waste quantities do not exceed 2 tons per day in Al-Mahrah and Hadramawt, while the operational capacity of grinding factories ranges from 50 to 300 tons per day.

Monitoring by the Marine Science and Biological Research Authority shows that environmental violations continue because of the lack of effective oversight, placing Yemen’s coasts on the brink of environmental and economic catastrophe. According to the ministerial committee’s report, these factories threaten the sustainability of fish resources, as their operational capacity exceeds the country’s annual production capacity, accelerating marine desertification and reducing fish generations capable of reproduction.

The report concludes that continued operation of grinding factories in this way will cause permanent imbalance in the marine environment, the loss of a basic food source for fishing communities, and a threat to the future of the fisheries industry in Hadramawt and Al-Mahrah.

Passing blame behind closed doors

As field evidence and official documents accumulated, it became necessary to turn to the government bodies responsible for overseeing these factories. Their responses, however, were contradictory. In Hadramawt, the head of the General Authority for Fisheries in the Arabian Sea, Yeslam Bablghoum, says some factories continued production “in blatant defiance” of suspension and shutdown orders.

During this investigative report, it became clear to us that the official authorities themselves lack a unified vision regarding the operation of grinding factories, and that these factories continue their environmentally destructive activity amid a broad landscape of conflicting interests and pressures, while fishermen and the marine environment remain the most harmed and threatened parties in this equation.

He said the authority was forced to resort to the judiciary to obtain a ruling to shut down the King Fisher factory, which violated licensing conditions by operating only a grinding unit without completing the rest of the factory’s required components. He stressed that “no factory has been licensed as a specialized fish-grinding factory.” Yet our field inspection and interview with the factory’s owner showed that King Fisher’s machines are still operating.

Meanwhile, the head of the General Authority for Fisheries in Al-Mahrah, Abdul Nasser Kalshat, says grinding factories are currently operating within an organized investment framework and that no major violations have been detected. This contradicts the investment licenses we obtained, which show the factories were licensed as integrated fisheries facilities with grinding limited to fish waste only.

The testimony of Sabri Lajrab, Director General of the Marine Sciences and Aquatic Life Research Authority, Hadramawt Branch, reinforces this contradiction. He confirms that “the Investment Authority issues licenses to these factories even though they harm fish, especially sardines, and deplete small fish stocks.”

The head of the Al Hasi Fisheries Association in Hadramawt, Ahmad Abdallah Basir, also reports that “no fewer than 30 boats in Hadramawt operate trawling as a main supplier directly to grinding factories,” amid the absence of any effective oversight.

Taken together, the statements of Bablghoum and Kalshat on one hand and those of Lajrab and Basir on the other show that official bodies lack a unified position. The factories continue their destructive activity within a wide space of conflicting interests and pressures, while fishermen and the marine environment remain the most harmed and threatened. This is underscored by the statement of the Director of the General Investment Authority in Al-Mahrah, Hani bin Hamdoun, who confirms that “the problem today is the lack of coordination among the concerned government agencies regarding grinding factories.”

Government missteps and inconsistent positions have produced a series of contradictory decisions. On August 12, 2024, the Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation, and Fisheries issued a decision prohibiting the establishment of private fish-grinding factories and suspending existing ones in Hadramawt and Al-Mahrah. This firm stance did not last. Just three months later, on November 25, 2024, the ministry abruptly reversed course and issued another decision under the directives of Presidential Leadership Council member and Southern Transitional Council President Aidarous Al Zubaidi, allowing grinding factories to resume operations “out of consideration for investment and the circumstances of investors,” with an operational mechanism to be determined later.

This decision came despite reports and studies from research bodies, as well as recommendations from official investigation committees, all calling for halting marine environmental destruction by stopping the operation of unregulated grinding factories.

Although Yemeni law grants the Minister of Fisheries the exclusive authority to establish or shut down fish factories — a point emphasized by Minister Salem Al Soqtari in a decision expressing his dissatisfaction with the circumvention of his authority — the most recent decision issued under Al Zubaidi’s directives remains in force. Grinding factories cite it to justify their continued work, and it may lead to further expansion in the coming years.

This investigative report shows that continued operation of fish-grinding factories in this manner is not only a legal violation but also a real threat to fish resources and ecological balance along Yemen’s coastline. It deepens the damage and directly affects the lives of fishermen and their families, as thousands depend on the sea for their livelihood.

Urgent intervention is therefore essential, whether by shutting down noncompliant factories or converting them into integrated fisheries investments, while imposing strict oversight on production and exports. Only then can the sea remain a source of food and livelihood, and the next generation of fishermen inherit a future similar to that of their fathers: one full of life and opportunity, not emptiness, depletion, and destruction of their marine environment.

*The exchange rates used here (1,600 Yemeni riyals to one US dollar) are those used in areas under the control of Yemen’s internationally-recognized government.

*Raseef22 contributed to the facilitation and oversight of occupational safety during the execution of this investigation. The publication also received consent to publish this story in both Arabic and English.

*SafeBox contributed to logistical support and the preservation of the investigation’s documents during the fieldwork for this investigation.

*This investigation was prepared and produced with support from the Pulitzer Center.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!