During a summer back home in 2022, I found myself lounging around the house, moving lazily between the sea and the comfort of my air-conditioned room as the scorching Tunisian heat simmered outside.

I spent my time watching films that explored parts of me I rarely got to see on screen: being both queer and Arab. I was watching these films alone, worried I’d blush or make a comment that might give something away—what if I laughed too hard at a line, explained a scene too precisely, or just looked like I knew a little too much?

As a queer North African woman, I tried and failed to connect with shows like The L Word—the glossy cult American drama about a tight-knit group of mostly white lesbian women, living in Los Angeles, who spent their free time having sex or fighting about it. The show’s queerness was loud, visible, but oddly de-politicized, and that just didn’t feel like my reality. I am an Arab first, and queer second—not the other way around. That nuance, that prioritization, changes everything: the language we use, how we move our bodies, what we say (or don’t say) to each other; it dictates the spaces in which we evolve.

I am an Arab first, and queer second—not the other way around. That nuance, that prioritization, changes everything: the language we use, how we move our bodies, what we say (or don’t say) to each other; it dictates the spaces in which we evolve.

So, when I stumbled upon Caramel (2007), directed by and starring the Cannes Jury Prize winning Lebanese filmmaker Nadine Labaki, it felt like finding something hidden but precious. The title itself felt like I had arrived at home: sticky, warm, a little sweet, and possibly dangerous. I pressed play.

Five women, a beauty salon, laughter, pain, and their mundane routines. The film’s gentle cadence—the way it lingered on women’s conversations, glances, frustrations—wasn’t like anything I’d seen before. It didn’t scream queerness—it suggested it. And that was enough to make me lean in.

Nearly twenty years on, why does Caramel still hit so hard? Because it speaks the language I speak. The film’s Beirut may no longer exist, but it certainly shows a queerness common across the region—one that still exists in ambiguous spaces, in hyperfeminine places like the tucked-away, frosted-glass hair salons.

The film follows Layale, Nisrine, Rima, Jamale, and Rose, played mostly by non-professional Lebanese actresses. Labaki said she wanted people “you’d look everywhere in life for.” Their world is the beauty salon: a microcosm of secrets, jokes, and heartbreaks. Layale is having an affair with a married man; Nisrine is engaged but fears her fiancé will discover she’s not a virgin; Jamale, a middle-aged actress, is terrified of aging; and Rose, an older seamstress, looks after her sister with dementia while her own chance at love quietly slips by. And then there’s Rima (played by Joanna Moukarzel), dressed in pants and tees in her very masc and lowkey wardrobe, refusing to wear makeup, flirting with no man and utterly uninterested in doing so, who stands apart from the rest.

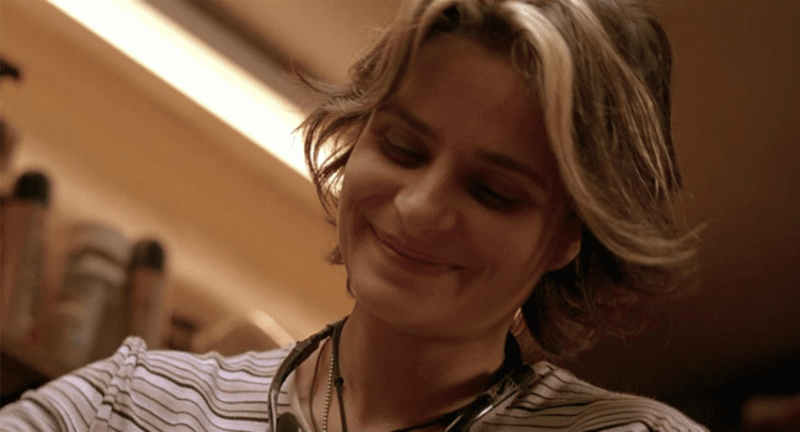

Moukarzel plays Rima with relaxed intensity, her attraction to women felt not through declarations, but through her gaze, gestures, and absences. One of the regular customers, Siham, seems to notice her, too. Their interactions build slowly, beginning when Siham singles out Rima to wash her hair. In the privacy of the salon’s backroom, Labaki frames the scene with care: nervous smiles, gentle touch, prolonged eye contact. It’s delicate, but charged.

Labaki frames the scene with care: nervous smiles, gentle touch, prolonged eye contact. It’s delicate, but charged.

Scholarship on queer representation in Arab cinema is sparse, but the few scholars who have tackled it offer language for what often goes unspoken or unnamed.

Lebanese scholar Maria Abdel Karim describes how “exchanging looks and smiles while Rima gently shampoos Siham’s hair is the way Labaki portrays the lesbian attraction between the two women.” Film scholar Patricia White, in her book Women’s Cinema, World Cinema: Projecting Contemporary Feminisms, called it “ultimately erotic,” a “stand-in for lesbian sex.” Labaki herself explained in a 2008 interview she wanted the film to include queerness without censorship—to still be accessible, visible, and accepted in mainstream Lebanese cinema. “You have to cheat in a way where people get the message without bluntly seeing it,” she said. “Many people live with [queerness] in secret, but there are also many victims and others who have problems dealing with it in public… They end up hating their bodies and hating themselves.”

Rather than sensationalizing queer desire, Labaki chose to show how it quietly survives inside contradiction. Rima never vocalizes her desire. Syrian academic and gender theorist Iman al-Ghafari, writing in the journal Al-Raida (2002), argues that “the lesbian identity doesn’t seem to exist [in the Arab world], not because there are no lesbians, but because practices, which might be termed as lesbian in Western culture, are left nameless.” Ghafari’s critique is what Labaki captures so precisely: Rima’s queerness is coded—not invisible, but indirect. In their book Queer Images: A History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006), film historians Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffin discuss how queer subtext often surfaces through visual cues and indirect gestures—a method long used by Arab filmmakers, from Youssef Chahine’s dancing men and lingering looks to Nadine Labaki’s suggestive bottle of shampoo.

Throughout the movie, Siham returns to the salon to have Rima wash and blow-dry her hair, still without confession and no explicit turn. But the repetition of their private act—the washing, the glances, the intimacy—builds a sensual rhythm for the viewer. As Abdel Karim noted, Caramel resists mainstream queer portrayals and instead focuses on “secrecy, revelation, and the voyeuristic nature of attraction in restricted social spaces.” That restraint felt radical, and a Letterboxd user, reviewing the film nearly two decades after its release, put it best: “Washing someone’s hair really is the most sensual thing ever, huh.” The comment has over 300 likes.

In one scene, Siham jokes that cutting her hair short would make her family “go crazy.” But by the film’s end, she lets Rima cut it. The moment, albeit fleeting, felt like a small rebellion, a sort of hopeful ending and quiet resolution for the both of them.

Evidently, the Arab beauty salon is more than a workplace. It’s a refuge. As Labaki said herself in a 2008 Vulture interview, the salon is where “women are amongst themselves and can feel comfortable. Things happen there that can’t happen outside… You have a special relationship with the person who makes you more beautiful; they need to see your thoughts and your truths.”

In that particular space, queerness isn’t practiced overtly, but it is held in the fabric of womanhood and sisterhood. Rima isn’t an outsider. She’s one of the girls. She’s not an outcast: she belongs to this Beirut, to the hair salon.

Caramel’s queerness is faint, but it is undoubtedly present. And maybe that’s what queer Arab representation needs sometimes: the suggestion, the possibility, the unspoken acknowledgment that we are here, amongst the others, amongst the ‘mainstream.’ The film doesn’t pretend to solve the dilemma of queerness in the Arab world, nor does it center it. It’s not about being gay. It’s about being women, showing up for each other, and existing unabashedly among our communities and in our cities.

The film doesn’t pretend to solve the dilemma of queerness in the Arab world, nor does it center it. It’s not about being gay. It’s about being women, showing up for each other, and existing unabashedly among our communities and in our cities.

That summer, I didn’t come out or make any big decisions with regards to my queerness. But I saw a bit of myself on that screen: not shouting, not politicizing, just living. And that, in itself, was a milestone. Since then, I haven’t seen any other movies that spoke to my sexuality in such subtle terms. Some critics deemed the film too soft in its lack of outward political criticism. But for me, its softness is political. In a world where queer Arabs are often sensationalized, Caramel lets us breathe.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!