I often hear the familiar ding! from a voice note sent on WhatsApp coming from my mother’s phone when sitting in my living room. She never uses her headphones, so a trail of voices usually follow each other, greeting her from locations across the world. A grail of As-Salamu Alaykum from London, from Saudi Arabia, from Holland, from Kenya, from Mogadishu.

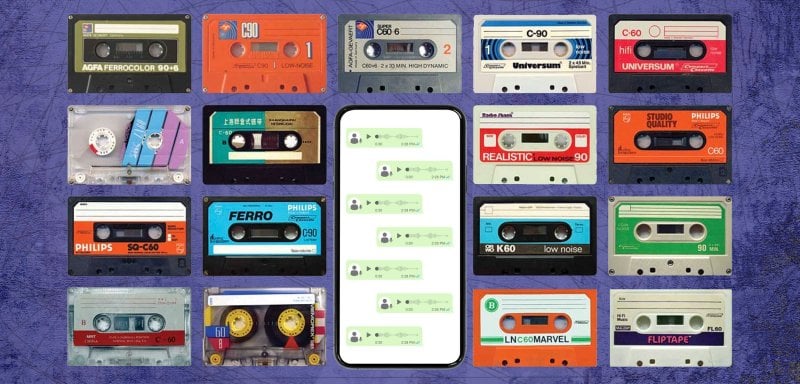

My mother, and older relatives, use WhatsApp in a specific way — differently from how the younger generations use it. During the 1990s and the early 2000s, Somalis sent cassettes and video tapes to families abroad, sharing stories and updates from where they were, which has now been replaced with the ease of WhatsApp group chats. Cassette tapes were an accessible way to keep in touch: you didn’t need to know how to write well, you just recorded your voice to send to your loved ones. Being part of a global diaspora meant that families and friends who once lived in the same towns were now scattered across different communities around the world. With this separation came creative ways to stay in contact.

In line with Somalia’s rich oral tradition and knack for storytelling, cassette tapes and voice notes were the obvious choice for a popular mode of communication that transcended borders. Somali stories and skillful prose are passed down through generations; known widely within popular culture as the ‘nation of poets,’ poetry is a fundamental form of verbal expression and societal tradition.

How voice notes are used within the Somali communities today can trace the evolution of communication between the diaspora throughout the years and its roots to wider Somali oral traditions. These mediums, from the voice note to the neighborhood group chat, became a lifeline for those of us who hailed from a community-centred society that dispersed drastically into the different lives demanded of us in Europe, North America and beyond.

Archaeologist Sada Mire’s work, which focuses on sustainability and human diversity through the framework of heritage and archaeology, highlights how oral transmission has historically helped preserve Somali experiences. Poets and storytellers are not simply additions to Somali culture but also function as the mass media, which can explain why poets are highly respected and core members of Somali society.

In line with Somalia’s rich oral tradition and knack for storytelling, cassette tapes and voice notes were the obvious choice for a popular mode of communication that transcended borders. Somali stories and skillful prose are passed down through generations; known widely within popular culture as the ‘nation of poets,’ poetry is a fundamental form of verbal expression and societal tradition. Gabay, a form of spoken poetry, is performed by both men and women, and typically chanted or recited in specific rhythm. Buraanbur is poetry only composed by women is accompanied with drumming and dance, especially at weddings. Both are examples of how these oral traditions manifest themselves in Somali pastimes.

The advent of WhatsApp ushered in the various and creative uses of voice notes and group chats. I watched how my mother and my older relatives used those features in a multitude of ways — group chats became ways to connect all relatives with the same family names.

These tapes also formed an essential part of Somali life and community efforts have sought to capture this. The Dhaqan Collective, a cultural heritage collective based in Bristol, captured this cultural tradition in their archival project, ‘Camel Meat and Cassette Tapes,’ which explores the various ways these tapes were used within the diaspora in the 80s and 90s.

Oral traditions also travelled with Somalis across the world. . The storyteller, typically anybody in the family who was gifted at telling stories, would call out sheeko sheeko! — story story! — and the children present would excitedly respond with sheeko *xariir! This prompted the storyteller to delve into a fantastical tale to capture the children’s attention.

I have memories of my father and my older cousin telling us a multitude of stories, often involving talking animals such as hyenas or goats. One story I faintly remember included the tale of a girl whose brother had turned into a goat. He sang to his sister so that she could recognize him and let him back in their home.

As calling cards became obsolete, the emergence of WhatsApp shifted communication globally. With a touch of a button, you could suddenly call people internationally, without the hassle of buying cards and hurrying to have a conversation before the credit ran out. The advent of WhatsApp also ushered in the various and creative uses of voice notes and group chats. I watched how my mother and my older relatives used those features in a multitude of ways — group chats became ways to connect all relatives with the same family names. Voice notes were the connecting thread that ran through these group chats – all of them starting with the mandatory Asalamu-Alaykum Wa Rahmatullahi Wa Barakatahu.

It was also used for Quran classes, ayuuto — a traditional rotating mutual fund, and also raising money for those in the community who were in need, whether for funerals, weddings, or any other necessities. Although Somali oral traditions typically took the form of storytelling and poetry, it also evolved with the contexts we are living in, whether that was necessitated by war or technological advancements. Oral traditions aren’t solely preserved for special occasions but continue to permeate through the narration of our daily lives and routines. Voice notes are part of this oral lineage.

In the chaos and rush of daily life, these messages provided an opportunity for people to slow down and take a moment to check in with each other. They even became sites of reunions. In these group chats, I saw how families and neighbours sometimes found each other, years later: my mother once recognized a name in a sea of voice notes and realised it was an old neighbour from her hometown in Somalia who now lives in Canada.

To be part of a global diaspora and spread out as we are, you find comfort with communities and people you knew from back home. I only need to ask my mum and relatives how they know this or that person before they delve into a story about being neighbors in their hometowns of Buur Hakaba and Mogadishu, explaining that people I thought I was related to were actually connected to us by tribe and proximity.

We have a word for missing something or someone in Somali: to xiis. This also translates to yearning and longing. In a Somali family, you grow up witnessing a specific longing for your homeland, not the homeland of today but of yesteryear, the homeland they grew up in and the pain accompanied with knowing that they may never see that life again.

In the chaos and rush of daily life, these messages provided an opportunity for people to slow down and take a moment to check in with each other. They even became sites of reunions.

Almost overnight, the country you remember, the sea you swam in, the people you grew up with and went to school with, the cafes, cinemas and shops you visited, changed drastically and disappeared. Growing up, conversations I overheard from my parents and relatives regarding Somalia always ended in common phrases such as, ‘may God bring peace to our land,’ the renewal of their commitment to and a pledge to sustaining hope for their return to our land.

Note: *The ‘x’ in Somali is pronounced like ح in Arabic.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!