Like many other villages and towns in occupied Palestine, Lajjun—once a prominent village northwest of Jenin—saw its inhabitants forcibly displaced during the 1948 Nakba. Now, Israel plans to build a tourist park on top of the stolen land. This move threatens to erase the remaining features of the village and obscure evidence of the ethnic cleansing Israel conducted during the Nakba. During that time, Israel expelled the residents of 530 other Palestinian villages, which were then completely or partially destroyed.

The Israel Land Authority is spearheading this plan. Regional councils associated with the settlement Megiddo and other settlements established on parts of Lajjun's land and different displaced villages such as Khubbayza and al-Rawha are also taking part. These councils aim to serve the Israeli community residing in these settlements.

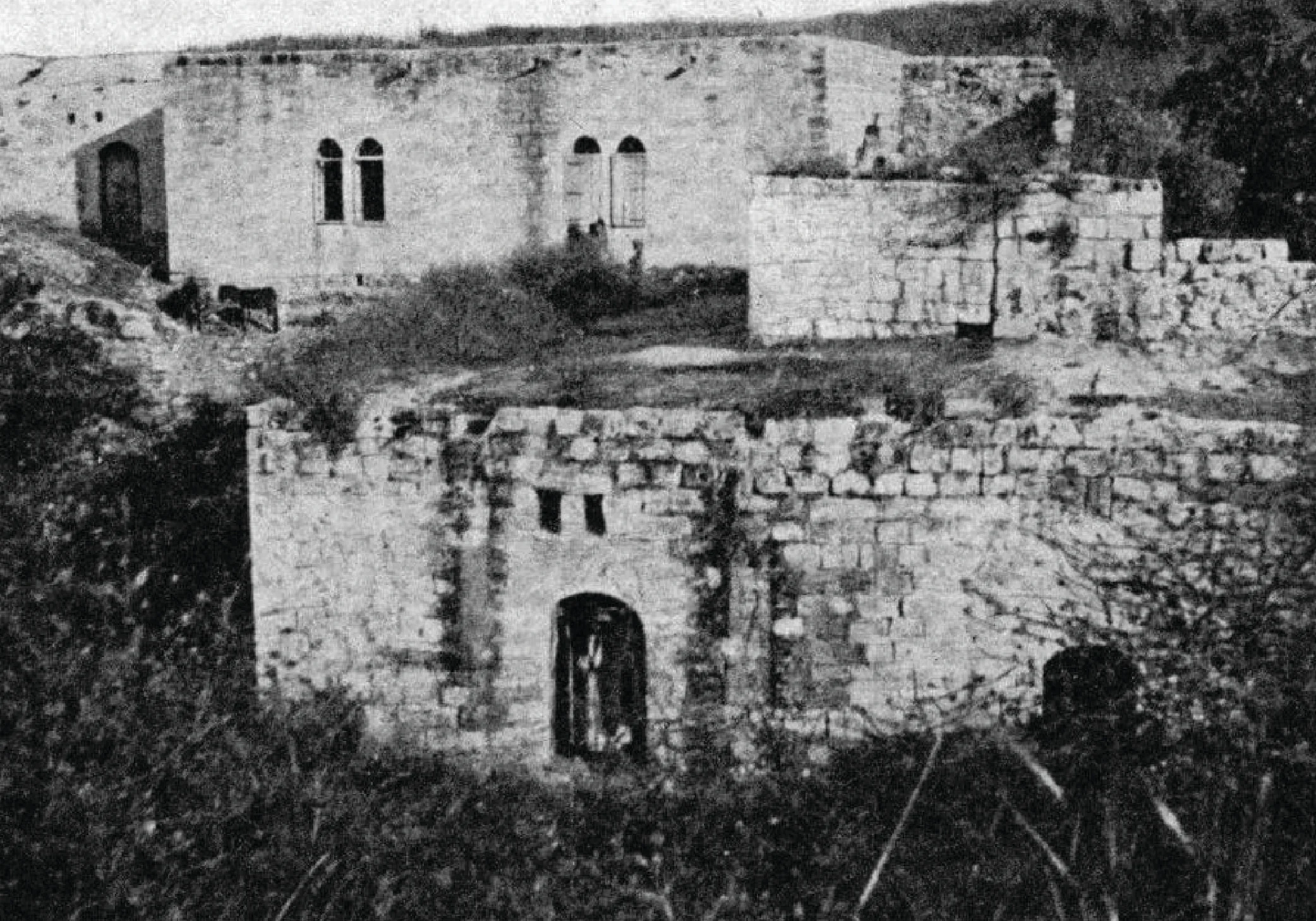

The tourist park plan will erase the remaining landmarks that indicate the village's history, such as its mosque, wheat mill, cemetery, and some of the partially destroyed house walls. It also severs the connection displaced residents of Lajjun have with their village. Relocated during the Nakba to nearby towns, they became refugees in their own country, living just a few kilometers away from their land, to which they are not allowed return.

If the plan proceeds, Lajjun and fourteen other ethnically cleansed Palestinian villages in the al-Rawha area, south of the Carmel Mountains, will be turned into a park. This will erase their landmarks, just as other plans have done to other villages.

Like many other villages and towns in occupied Palestine, Lajjun—once a large and prominent village northwest of Jenin—saw its inhabitants forcibly displaced during the 1948 Nakba. Now, Israel plans to build a tourist park on top of the stolen land. This move threatens to erase the remaining features of the village and obscure evidence of the ethnic cleansing Israel conducted during the Nakba.

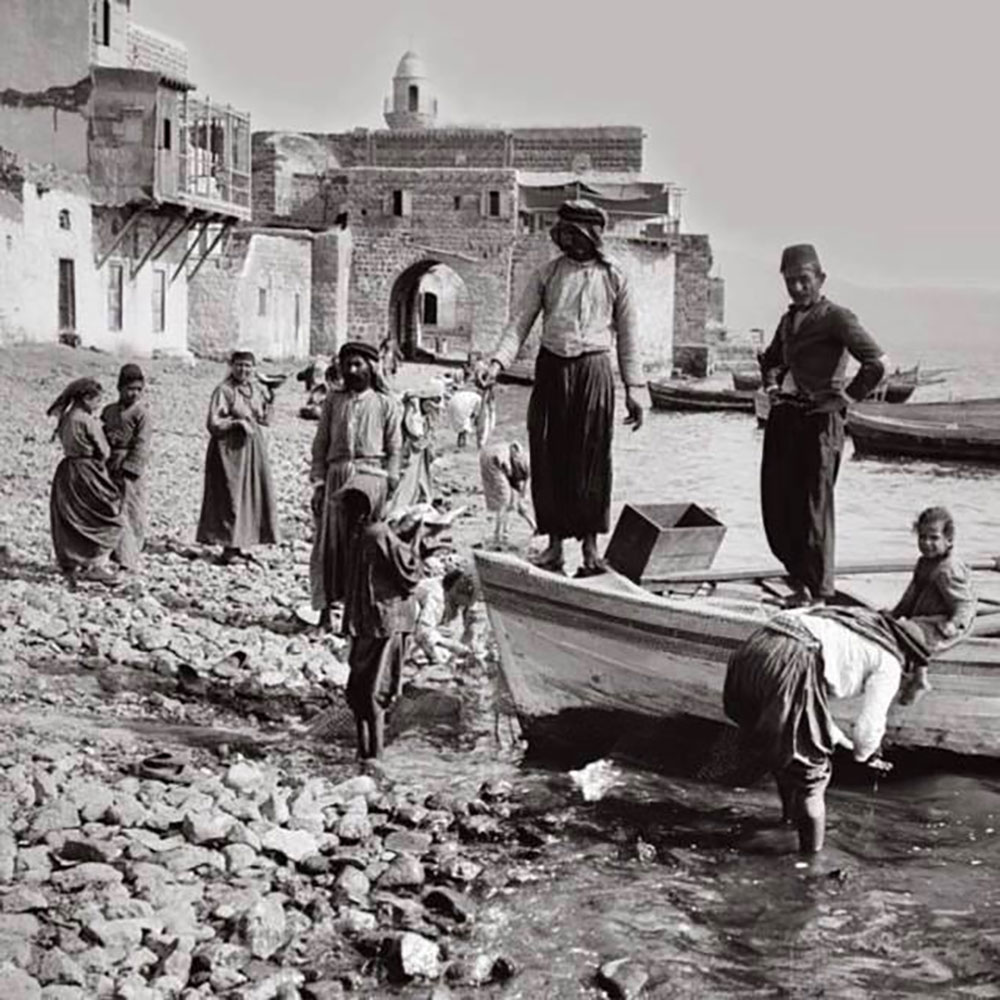

Similar instances include how Israel built a parking lot over a mass grave in Tantura, how it turned the empty homes of the forcibly displaced villagers of Ein Hawd into studios for Israeli artists, and how it reforested the village of Saffuriyya, erasing its Palestinian characteristics and natural terrain.

Lajjun before its residents were forcibly displaced in the 1948 Nakba.

Lajjun before its residents were forcibly displaced in the 1948 Nakba.

Lajjun before its residents were forcibly displaced in the 1948 Nakba.

Israel’s Absentee Property Law: A tool for seizure

"Lajjun was a thriving, central village, connecting eastern and western Palestine through its bus station. However, during the Nakba, its residents were forcibly displaced and the village was emptied of its people. In the 1970s, all of its land was confiscated under the Absentee Property Law and the Land Acquisition for Public Purposes Law," lawyer Hussein Abu Hussein tells Raseef22.

The Absentee Property Law, enacted in 1950, classifies anyone who fled or was forcibly displaced from the borders drawn in 1948 as an "absentee." This law allows the state of Israel to seize Palestinian property and do with it as it pleases.

Over the ensuing decades, Israel leased these lands to Jewish settlers and subsequently sold them to the Israeli private sector, settlement associations, or governmental bodies.

For activist Karam Jabareen, the village—with its valley, springs, and trees—held value long before he understood the meaning of the Nakba. "This innate love for Lajjun has turned into a struggle to preserve the land. It was only later that I understood the Nakba, our forced displacement, and the afforestation Israel undertakes to erase traces and evidence of its crimes."

The Absentee Property Law has been a key tool in preventing displaced Palestinians from returning to their homeland, and in legally cementing the permanent seizure of their properties.

Abu Hussein explains, "Using this law, numerous settlements have been established on the lands of Lajjun, such as the Megiddo settlement. These span thousands of dunams, yet house only a few hundred residents. To further its settlement project, Israel recently drafted this detailed plan to build a park on the remaining thousands of dunams of Lajjun."

Before the Nakba, the village's land spanned about 36,000 dunams and had a population of approximately 1,300 people. Every resident was forcibly displaced. Today, most of them reside in the nearby town of Umm al-Fahm.

The Megiddo settlement, which was established on the land of Lajjun village.

The Megiddo settlement, which was established on the land of Lajjun village.

The Megiddo settlement, which was established on the land of Lajjun village.

What we are witnessing is a systematic policy to erase the remaining traces of the village and seize its history—a move even more devastating than the land confiscation itself.

A living connection with a displaced village

In some Palestinian villages inside Israel, displaced residents maintain a strong connection with their ancestral lands. This is seen in villages such as Briam and Iqrit in the Upper Galilee, Ma'alul near Nazareth (al-Nasirah), and Lajjun.

Ziyad Mahameed, 81, was displaced from Lajjun on May 30, 1948. However, he makes daily visits to his village and roams its fields, often encountering other people while there.

“Sometimes I find young couples there. I approach them to talk to them about the history of the village, just as I would tell my grandchildren. I feel it's important to do this to counter Ben-Gurion's claim that 'The old will die, and the young will forget.’”

"I used to welcome visitors, sharing the village's history and serving them coffee next to the ruins of my house. Each time, I would imagine the courtyard as it once was, untouched by destruction," Ziyad says with a deep sense of loss.

He believes that building the tourist park will erase the remaining evidence of what happened during the Nakba.

“Sometimes I encounter young couples. I approach them to talk about the history of the village, just as I would tell my grandchildren. I feel it's important to do this to counter Ben-Gurion's claim that 'The old will die, and the young will forget.’”

"What's happening is more than just the confiscation of our land. They are trying to confiscate our memories and emotions as well. If they want them, they'll have to take them by force, because they'll never get them willingly," he asserts.

For activist Karam Jabareen, 27, the village—with its valley, springs, and trees—held value long before he understood the meaning of the Nakba.

"This innate love for Lajjun has turned into a struggle to preserve the land. It was only later that I understood the Nakba, our forced displacement, and the afforestation Israel undertakes to erase the traces and evidence of its crimes," Karam tells Raseef22. Karam is part of the third generation of originally displaced residents.

He describes the relationship between Lajjun and its neighboring people as if it were their second home. "This home of ours is also facing erasure, even in its name, as Israeli authorities have renamed Ayn al-Hejja to 'Nahal Keini.'"

"I used to welcome visitors, sharing the village's history and serving them coffee next to the ruins of my house. Each time, I would imagine the courtyard as it once was, untouched by destruction."

"We are working to deepen the narrative of the displaced village of Lajjun, which embodies the concept of the Nakba. We welcome foreign delegations and share Lajjun’s story with them, sending a clear message to those behind the tourist park project. Even 76 years later, the village remains alive. We are an extension of our ancestors, and their struggle, supporting them in our collective struggle for identity."

Tantura village on display before its forced displacement.

Tantura village on display before its forced displacement.

Tantura village on display before its forced displacement.

Tantura beach, on top of which many settlements have been built. Only one remaining Palestinian home exists following the Tantura massacre and forced displacement.

Tantura beach, on top of which many settlements have been built. Only one remaining Palestinian home exists following the Tantura massacre and forced displacement.

Tantura beach, on top of which many settlements have been built. Only one remaining Palestinian home exists following the Tantura massacre and forced displacement.

Will resisting the project succeed?

Various Palestinian groups are trying to resist this plan. This includes the Popular Committee in Umm al-Fahm, the Committee for the Defense of the Lands of al-Rouha, and the refugees of Lajjun village.

"They've been trying to implement this plan for seven years and have constantly contacted Palestinian councils for approval. We completely reject any type of compromise, and firmly believe in our right to return," says Mohammed Mehanna to Raseef22. Mehanna is a member of both the Committee for the Displaced and the Heritage Committee of Lajjun.

"We have submitted a legal petition to the organizing committee, outlining our historical right to the land. The committee is expected to make a decision by the end of July 2024." "We are not relying on any legal or political objections and are already aware of the likely outcome," Abu Hussein asserts.

"Typically, objections to architectural plans are submitted based on engineering claims. However, our main argument is based on humanitarian law. What is happening in Lajjun violates humanitarian law, and our connection and right to the land," he further elaborates.

"We are working to deepen the narrative of the displaced village of Lajjun, which embodies the concept of the Nakba. We welcome foreign delegations and share Lajjun’s story with them, sending a clear message to those behind the project. Even 76 years later, the village remains alive. We are an extension of our ancestors, and their struggle, supporting them in our collective struggle for identity."

Abu Hussein highlights the daily policies Israel implements in Palestinian villages originally displaced in 1948 represent cultural and demographic replacement. He cites a similar plan aimed at confiscating the land of the displaced village of al-Bassa in the Upper Galilee. This plan began after the historical landmarks of the village were demolished.

"We need to fight a political battle against these plans and rally popular support to make a tangible impact," Abu Hussein emphasizes.

Mehanna believes in popular struggle, having witnessed its success in 2013 in halting Israel’s electricity plan in al-Rouha. After a seven-year struggle, The Popular Committee for the Defense of the Lands of al-Rouha managed to reroute 80 percent of the Israeli power line off of Palestinian land.

"We must intensify our popular struggle if the planning committee does not rule in our favor," Mehanna asserts.

"Lajjun once had a vibrant life, with a thriving people and culture. What is happening now is a systematic policy to erase the remaining traces of the village and confiscate its history. Confiscating history is even crueler than confiscating land. History will record the stand we take today."

"Lajjun once had a vibrant life, with a thriving people and culture. What is happening now is a systematic policy to erase the remaining traces of the village and confiscate its history. Confiscating history is even crueler than confiscating land. History will record the stand we take today."

Mehanna explains that the popular struggle currently involves organizing demonstrations, holding protest vigils, and conducting prayers on village land.

Activist Karam Jabarin notes that engineers have already begun surveying the area, and trees have been cut down to establish a power line.

"This project is more dangerous than it appears. The real danger lies in the fact that once it starts, it will be challenging to stop. The struggle must begin now."

Friday prayers on the displaced village of Lajjun, amidst the eucalyptus trees Israel planted after the Nakba.

Friday prayers on the displaced village of Lajjun, amidst the eucalyptus trees Israel planted after the Nakba.

Friday prayers on the displaced village of Lajjun, amidst the eucalyptus trees Israel planted after the Nakba.

Using nature and art, Israel hides evidence of its crimes

Israel's strategy of hiding the existence of depopulated Palestinian villages within its borders is not a new tactic. This strategy has been implemented through various policies, notably: afforestation, demolishing landmarks, and converting them into tourist sites.

The Jewish National Fund began afforestation campaigns in 1920 under the supervision of the British Mandate administration. This policy is abundantly noticeable in Lajjun, where Israel has planted non-native tree species, such as eucalyptus, cypress, and pine trees. This has altered the village's landscape and erased its identity.

"We need to fight a political battle against these plans and rally popular support to make a tangible impact". Engineers have already begun surveying the area, and trees have been cut down to establish a power line. "This project is more dangerous than it appears. The real danger lies in the fact that once it starts, it will be challenging to stop. The real struggle must begin now."

In other villages, particularly near major cities, Israel builds new settlements. Today, on top of the displaced village of Lifta, near Jerusalem, Israeli authorities are constructing settlement units, a shopping center, and a museum.

It is a rare instance for villages to remain as they were when their inhabitants were forcibly displaced.

In 1953, Israel transformed Ein Hawd, a village south of Haifa, into an artist colony. They renamed it "Ein Hod," turned the village mosque into a restaurant and bar, its homes into studios for Israeli artists, and its olive press into a gallery.

Palestinian refugees from Ein Hawd now live just a few kilometers away from their village. From some of their new houses, they can see their old homes and memories Israel stripped from them during the Nakba.

Ein Hawd village during an Israeli art event.

Ein Hawd village during an Israeli art event.

Ein Hawd village during an Israeli art event.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!