“I came out of prison and found myself in one that was even larger and harsher,” explains Amani, 34, from Aden. Amani, who was arrested on March 20, 2012, spoke to Raseef22 about the societal stigma that she faced upon her release from prison.

“I was full of ambition,” she shared, “I was engaged to a doctor, in my second year of university, but everything changed in an instant, as revenge against my father, a political dissident.” She reflects for a moment, before explaining, “That day, I was returning home on a small bus when a woman boarded near the university gate, and sat next to me. I am certain it was her who planted a bag of drugs in my bag, which led to my arrest.”

“Drugs!” She repeats the word, as though still in disbelief, before continuing, “The traffic police stopped the bus, which doesn’t usually happen. They said that they received a report to search the bus, and they went straight for my bag. Within moments, they were asking me to get off the bus. They took me to the police station where they began to hurl a torrent of insults at me, specifically about my father.”

They put me in jail to extort my father

At first, Amani did not realize what was happening, thinking it was just a misunderstanding that would be cleared up within a few hours. However, she was detained for two weeks, denied any family visits, and subjected to physical and psychological torture, before being transferred to Mansoura Central Prison where she was tried on charges of promoting and selling drugs.

After her release from prison on fabricated charges and facing societal stigma, Amani attempted suicide. Her mother reprimanded her, arguing that it would bring shame to the family, as people might believe she had committed suicide due to being raped in prison.

She says, “It was a fabricated charge intended to harm my father, who suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized upon learning of what happened to me. After months of trial sessions and my father making the necessary concessions, the court declared me innocent and released me.”

However, beyond the prison walls, Amani’s ordeal was just beginning. Her fiancé left her, her older brother, who works abroad, announced that he would not return to Yemen due to the shame of her imprisonment, and her younger brother was cruel towards her during their father's absence.

“I felt as though I was dying a thousand times a day, isolated and trapped at home,” she says, recounting the despair that led her to attempt suicide. She was saved at the last moment. "Even then, my mother severely reprimanded me, saying I would have brought great shame to the family. She said people would have thought someone had raped me in prison and so I tried to kill myself."

Marriage to cover up scandal...

In 2015, a friend of her father's from Lahj proposed to Amani. She says the man, who was over 50, already married, and had six children, wanted to marry her to save her family from the disgrace and shame that had befallen them. Her father agreed immediately without asking for her opinion, "not that I would have objected anyway; I needed a place to escape to and disappear forever," she adds with a hint of resignation.

Yet, her past continues to haunt her, even now as a mother of three daughters. "I'm like a servant who must always obey. In the slightest disagreement with any of my husband's relatives or his first wife, they immediately label me a former prisoner. The label pains me, and I just keep silent."

Today, Amani lives in a state of constant anxiety about her daughters' future. She says, "Who will marry them with a mother who was once imprisoned? It feels like a permanent mark that I cannot erase, and it seems I will pass it on to my innocent little girls as well."

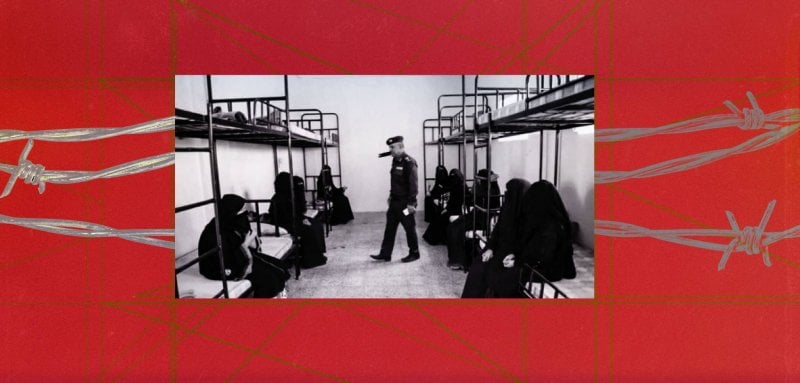

There are no accurate official statistics on the number of female prisoners detained in Yemen, but some information is available for prisons under the control of the legitimate government. Lieutenant Colonel Naqeeb al-Yahari, warden of the Mansoura Central Prison in Aden, stated in a press interview that there were 17 female prisoners in Yemen, seven of which were imprisoned in 2024 and five released within the same year.

He noted that the crimes for which they were convicted ranged from murder, theft, and fraud, to moral offenses. Two prisoners were released in early 2024, but their families refused to take them back home.

Civil activist Saleh Al-Mudhaffar told Raseef22 that some families do not accept the women after they are released from prison. He said, "Families generally do not care about the reasons behind their imprisonment, or whether they were convicted or released for being innocent. Their main concern is what people, including relatives and neighbors, will say about them, and the shame it will bring."

Our families refused to take us back

Raseef22 spoke with several former female prisoners, some of whom confirmed that their families rejected them, forcing them to return to prison or seek support from organizations. They mentioned that some former prisoners were even killed by their relatives, particularly those convicted or accused of moral offenses or murder.

Families of Yemeni female prisoners often refuse to take them back after their release. According to activists, these families do not care about the reasons behind their imprisonment, or whether they were convicted or released for being innocent. Their main concern is what people will say about them, and they fear the shame it will bring."

Dr. Sabah Rajeh, head of the Yemeni Women’s Union in Taiz, tells Raseef22, “Many families have indeed refused to accept their daughters after their release from prison, leading these women to seek refuge in associations, shelters for abused women, or centers like Al-Amal. They avoid media appearances in an attempt to forget what happened to them.”

Human rights activist Ibtehal al-Kumani noted that there are between five and seven women in Dhamar prison who have completed their sentences but remain in prison because their families refuse to take them back.

She explains, “The customary practice in Yemeni courts is that a female prisoner is only released and handed over to a first-degree relative who must sign for her. However, some families disown their daughters, especially if they were convicted of moral offenses, to avoid the stigma, forcing them to stay in prison even after having completed their sentences.”

She added, “This issue is often bypassed in courts in southern Yemen and in Taiz, where the requirement for a relative to receive the released female prisoner is not enforced.”

Dr. Adel al-Sharjabi, a sociology specialist, explains that Yemeni society is an Arab tribal society where the value of honor holds a central place, especially in regards to women. This honor is mainly related to issues of adultery and sexual practices outside of marriage, which were traditionally dealt with within an informal justice system, namely customary law.

He says, “Women in tribal areas were not typically held accountable for other criminal matters, nor were they imprisoned. However, over the past four decades, women have been held accountable in formal courts for all civil and criminal cases, just like men.”

He notes that alongside this shift, an “extremist culture” has emerged stigmatizing women who are imprisoned, despite men not facing the same stigma for the same crime. “In some cases, families refuse to accept women or girls back after their release from prison, regardless of the crime for which they were incarcerated.”

Dr. al-Sharjabi finds it surprising that some Yemeni prisons require a male relative to be present to release a female prisoner who has completed her sentence. He believes this practice violates the Prison Organization Law and its executive regulations, as well as the Criminal Procedure Law.

According to him, the responsibility for rectifying these issues lies primarily with the state and, subsequently, with civil society organizations. “These entities should organize and implement programs to reintegrate women released from prison into their families and society.”

“I was tried without a lawyer”

Rola, a 27-year-old widow and mother of two, was accused and convicted of home robbery and assault with a weapon in the Al-Hijaz area of Aden. She was sent to the central prison in November 2022.

She tells Raseef22 that she was detained, beaten during interrogation, and falsely accused of a crime she did not commit. Initially, she had no legal representation because her family had disowned her. “My mother was the first to abandon me, saying I had brought shame upon them,” she says.

Due to families refusing to take them back, many female prisoners join shelters and associations for abused women. Currently, there are between 5 and 7 women in Dhamar prison who have completed their sentences but remain there because their families refuse to take them back.

Rola mentioned that a female security officer in the prison sympathized with her and helped her secure legal representation. After 19 months, she was released on bail in May 2024, with the help of the female officer. “She was sure that I was innocent and stood by my side, and when my family refused to take me back. She welcomed me into her home and took me in, and I am still there with my two children.”

Psychologist Dr. Shaimaa Naaman explained to Raseef22, “Yemeni female prisoners often suffer from worsening depression and anxiety while inside prison as a result of the harsh conditions they face there.”

She added that these women also experience “feelings of hopelessness, frustration, and a sense of powerlessness and weakness. They also suffer from psychological trauma and post-traumatic stress disorders, as many of them have faced physical and psychological abuse.”

Dr. Naaman notes that the psychological pressures on these women intensify “due to their initial separation from their families and imprisonment, and then the shock they experience upon release when their families reject them or when they face societal stigma. Some of them already feel guilty and suffer from the consequences of this guilt.”

She explains that women released from prison face “low self-esteem, a sense of brokenness, and a lack of self-confidence. They feel shame and frustration, which results in chronic depression and anxiety. This can escalate to them isolating themselves from society or even attempting suicide.”

Do new opportunities exist for female prisoners?

Waheeb al-Khidr, the director of training and rehabilitation at the Aden Central Prison, states, “Yemeni prisons are working on training and rehabilitating female prisoners inside the prisons, teaching them crafts and trades with the support of civil and international organizations.”

Valentina Mahdi, the acting head of the Yemeni Women's Union in Aden, tells Raseef22, “We have worked in partnership with UNDP to economically empower female prisoners so they can acquire skills that enable them to support themselves and their families.”

Mahdi confirms the existence of agreements with international organizations “to economically empower women released from prisons by helping them start small craft projects, allowing them to continue their lives in a dignified way, reintegrate into society, and gain new life opportunities.”

She called on the state and international organizations to support Mansoura Central Prison “by equipping it with workshops, such as carpentry or a local bakery, and other facilities that would provide the women with skills qualifying them to work inside the prison. The prison administration could sell their products to cover the costs of their care and provide good services to them.”

Dr. Sabah Rajeh, head of the Yemeni Women's Union in Aden, informs Raseef22, “Our organization regularly visits the female prisoners and provides psychological support to those released. We help them engage in work they are skilled at or a craft they want to learn. Afterward, we train them or assist them in starting a small project to serve as a source of income.”

Until recently, women were not tried "criminally" in Yemen. Yemeni courts required that a female prisoner be released only to a first-degree male relative. However, this practice has been bypassed in courts in southern Yemen and in Taiz.

Dr. Sabah adds, “The organization supports women released from prison by teaching them various skills, such as sewing, embroidery, making incense and perfumes, baking, knitting, and mobile phone repair, among other trades that provide them with experience and a source of income.”

She points out that many women who have been released from prison and abandoned by their families have “overcome societal and familial obstacles, establishing successful income sources with the help of the Yemeni Women's Union and international support. They have become leaders in their fields and achieved financial independence.” She adds, “This financial success has led some of their families to seek reconciliation and bring them back home.”

“That girl is dead”

Raseef22 attempted to contact former prisoners who have moved past their experience of incarceration and are now working to move forward in their lives. These women declined to speak about their experiences. We also contacted relatives of several former prisoners, who similarly refused to comment. Each offered an excuse, and some outright denied any connection to a particular female prisoner.

The father of a young former prisoner from Taiz mentioned that he took his daughter back after he confirmed that she was trustworthy, especially following her professional success, stating, “Leave the past behind; I don't want to discuss what had happened in the past.”

Conversely, the father of another former prisoner from Aden denied ever having a daughter who was imprisoned. When repeatedly asked about her, he angrily said, “That girl died a long time ago, and we don't even know where she is buried.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!