To everyone, and no one in particular: I am from the generation that lived through the blockade period—the siege imposed on Iraq after the invasion of Kuwait. At the same time, I did not fully experience it.

What I mean is that I experienced hunger and suffered from anemia because of the blockade. I would have likely died if it were not for fate having other plans for me.

But I was not really conscious and have no memories of this time, other than those my family told me, so now I believe I had lived through it.

At around nine or ten years old, a childlike awareness began to form in me. I began to understand that there were issues bigger than my small world—my room, our house, the river nearby; that there are conflicts more brutal, bloody, and volatile than the arguments between my sister and my brother's wife; and that there were thick walls that frustrate and degrade people more than the walls of my school. I began to understand that there are cruel enemies, more hideous than my peers who bullied me for my nose, ears, and the mole above my eye. If it were not for them, we could imagine a safer world.

At around nine or ten years old, I began to understand that there were issues bigger than my small world—my room, our house, the river nearby; that there are conflicts more brutal, bloody, and volatile than the arguments between my sister and my brother's wife; and that there are cruel enemies, worse than my peers who bullied me for my nose, ears, and the mole above my eye. If it were not for them, we could imagine a safer world.

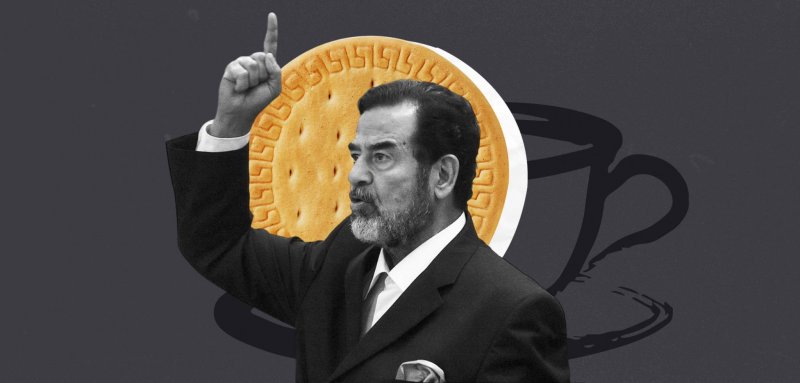

News about the war began to occupy more space in our lives than anything else. At lunch and dinner, my father and brothers always held a serious discussion about the war. Opinions varied between America's stern promise and the strength of the regime. Since the regime's television channel showed us soldiers, weapons, anthems, and Saddam Hussein smiling all the time, we assumed that Iraq would become the new graveyard for Americans.

With the invasion of Iraq, we saw Vietnam all over again. The Americans would lose the war, but at a great cost: the ruin of Iraq. In any case, no generation wants to be an example for other generations if it requires sacrificing their lives.

With the invasion of Iraq, we saw Vietnam all over again. The Americans would lose the war, but at a great cost: the ruin of Iraq. In any case, no generation wants to be an example for other generations if it requires sacrificing their lives.

A lost poem: "Let the statue fall"

As the war approached, some families decided to leave the cities for the countryside. In the countryside, we contented ourselves by digging up places to sit in our orchard. In a single day, my father managed to clear these spaces, and we lined them with locally made carpets. We slept there during the day. However, we returned to our rooms at night, believing that death would seem less brutal when we slept.

The war broke out immediately. We couldn't believe that the ghost of Saddam Hussein would vanish within days, that life would seem less bleak, that the Baathists would emerge in masks and hiding, this time evoking pity even from the families of their victims.

News about the war began to occupy more space in our lives than anything else. At lunch and dinner, my father and brothers always held a serious discussion about the war. Opinions varied between America's stern promise and the strength of the regime. Since the regime's television channel showed us soldiers, weapons, anthems, and Saddam Hussein smiling all the time, we assumed that Iraq would become the new graveyard for Americans.

It was precisely during this period that I began trying to write poetry. However, my lack of knowledge and experience led me to struggle to write for more than seven days. Then came the moment when the tyrant's statue fell and toppled to the ground, decapitated, and it encouraged me to write a striking poem. I remember writing it in blank verse, and that one of its lines ended with "Let the statue fall."

The poem remained in my desk drawer for days. I repeatedly revised it until I found it worthy of being aired on television. I hid it, waiting for the right moment to broadcast it. At the time, I was only twelve years old, but the waiting went on, and the poem was neglected. Eventually, it joined a large number of my poems I threw into the fire as I entered a new phase of writing.

I'm happy to rewrite it today, but would that still be a meaningful poem? I mean, can a poet recover and revamp a piece of work, two decades after its moment had passed? I'm seriously considering rewriting it, so bring me a people toppling a statue, just for the sake of some present-day credibility.

I remember when the Americans visited us at school and gave us school bags, pens, and boxes of biscuits. When I brought the biscuits home, none of us liked them. My mother even said that they tasted unbearable.

The American biscuits are terrible but their bags are good

During my childhood, I didn't live a life that any child should bear. I didn't know what chips or fancy sweets were. My father didn't take me to parks. I didn’t even know what bananas tasted like—even when I saw them on TV, I’d deluded myself into thinking they were just any ordinary fruit. That's not an exaggeration. It was a cruel hand to be dealt to be born in 1990 Iraq, where the siege begins after the war and the war begins after the siege, where a land free of a tyrant becomes a land run by colonizers. No matter how kind the Americans were at first, they scared us because we didn't understand their language. I remember when they visited us at school and gave us school bags, pens, and boxes of biscuits. When I brought the biscuits home, none of us liked them. My mother even said that they tasted terrible.

The American biscuits were the worst biscuits I had ever tasted, even though they may have been among the finest biscuits in the world. As for their school bags, they seemed good and useful. Just like that, one could benefit from the Americans and be disgusted by them at the same time.

During my childhood, I didn't live a life that any child should bear. I didn't know what chips or fancy sweets were. My father didn't take me to parks. I didn’t even know what bananas tasted like. That's not an exaggeration. It was a cruel hand to be dealt to be born in 1990 Iraq, where the siege begins after the war and the war begins after the siege, where a land free of a tyrant becomes a land run by colonizers.

I later learned that Americans have offered the world things beyond soldiers, rifles, and brute force. I came to know Walt Whitman’s poetry and grew to love him. Whitman was the poet who made me regain the ability to love this nation. Whitman, not George Bush, is the one who we should discuss at length, so that the nations and the peoples can be in harmony. Conversely, in place of Saddam Hussein, we should celebrate Nazem al-Ghazali for his beautiful voice, suit, and thin mustache (even if his mustache is thin). A thin mustache is just more moderate—the world has been ruined by enough thick mustaches like Saddam’s or half-musctaches like Hitler’s.

My sister and my brother's wife no longer argue

As time passed, American atrocities grew and intensified. For most of us, the biscuits were extremely unpleasant, and we felt a need to get rid of their taste. We were divided into three groups: those who refused to eat their biscuits ; those who found their taste pleasant; and those, including my family, who ate the biscuits but did not enjoy doing so. However, we didn’t feel morally responsible to cleanse ourselves of the aftertaste of American biscuits, nor to cleanse everyone else's palettes of the unpleasant taste.

I later learned that Americans have offered the world things beyond soldiers, rifles, and brute force. I came to know Walt Whitman’s poetry and grew to love him. Whitman was the poet who made me regain the ability to love this nation. Whitman, not George Bush, is the one who we should discuss at length, so that the nations and the peoples can be in harmony.

Suddenly, the civil war broke out, and car bombs and fake checkpoints were appearing everywhere. Everyone started to threaten each other, and all were equally deemed traitorous collaborators and agents who were pushing Iraq into an abyss.

In these times, a person's name or tribe could be reason enough to end their life. If one’s name or tribe did not clearly indicate his acceptance of “the biscuits,” he faced questions and scrutiny from a particular sect, depending on who had set up the checkpoint. One time a Shia checkpoint stopped a Sunni man, asking him about Jaafari jurisprudence and about the Imams. He said he knew nothing about history. However, so they would let him pass, he said that he loved the imams more than God. Other versions of this story recount the same encounter but with the sects switched. There are numerous other tragic and bizarre stories from all sects during this period of Iraqi history.

The Americans had given us school bags, boxes of biscuits, and a governing council. Now, the American gifts total less than a single biscuit, school bag, or a “day of democracy” without bloodshed.

At home, my sister and brother’s wife still had their differences. Strangely enough, though, they both agreed when it came to the taste of American biscuits.

My brother's wife said, "[The biscuits] taste good." My sister agreed, "Especially with tea." The other added, "Or with milk," and they inevitably started to argue again. That Iraqi summer was brutal, and a dispute over bloodshed was no more important than a dispute over biscuits.

The time was marked by losses too painful for its people to forget. Perhaps nine out of every ten Iraqis were lost to the war—brothers, sons, husbands, fathers, or close relatives. This is not an exact statistic, but then again, are there any accurate statistics from that time?

That Iraqi summer was brutal, and a dispute over bloodshed was no more important than a dispute over biscuits. The time was marked by losses too painful for its people to forget. Perhaps nine out of every ten Iraqis were lost to the war—brothers, sons, husbands, fathers, or close relatives. This is not an exact statistic, but then again, are there any accurate statistics from that time?

The Americans had given us school bags, boxes of biscuits, and a governing council. Now, the American gifts total less than a single biscuit, school bag, or a “day of democracy” without bloodshed.

My sister married, and my brother's wife has no one to argue with anymore. As for American biscuits, they are no longer American. Now we can’t stand any biscuits packaged in a box.

* The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!