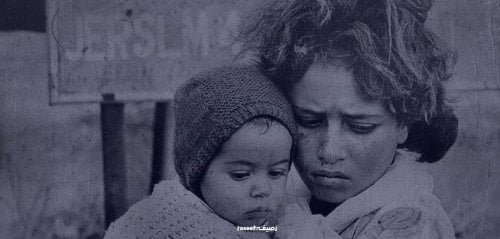

This article comes as part of our commemoration of the 76th anniversary of the Nakba, a collection of personal and collective archives from Nakba survivors. This year, we shed light on archives that have been obscured by time or that have lived on in the hearts of their owners, their children, and their grandchildren. We shed light on them as we lose the original souls who lived through the Nakba. Much of these stories exist due to their passing onto the next generations, who continue to honor their family and ancestors by preserving and sharing their tales and experiences as if it were one continuous narrative.

Read in English here and in Arabic here.

A few weeks after the start of this most recent Israeli aggression on the Gaza Strip, some families in the north began to evacuate southward, especially after Israeli threats and the declaration of northern Gaza as a military battle zone.

We, the people of the north, were forced to choose between staying in our homes, near our gardens and neighborhoods despite the looming danger, and going south, which was, at the time, less dangerous.

My family and I chose to stay in the north because we knew how difficult the conditions and consequences of displacement are, where there wouldn't be enough houses, clothes, beds, or books for the people.

I will never forget that attack. It was the most terrifying thing I had experienced in my life. Bombs rained down around us in the dozens. We were sitting and staring at the ceiling as we waited for the next bomb to drop on us. What if that actually happened?

On October 12, 2023, I was surprised to see my father, mother, and siblings pack their bags, leave our home in Beit Lahia, and head to Jabalia Camp, where my mother was born and raised. There, my grandfather and some of my uncles and aunts still live in the camp. My grandfather Talal would later pass away on April 14, 2024, in Jabalia Camp, where he refused to leave despite the bombing and complete destruction of his 70-square-meter house just a few months prior, in December.

We were not the only ones who carried all they could fit in their bags on their backs, bags filled with children's clothes, some bread, biscuits, identification papers, and a photo or two of the family.

We headed out on foot as particles of smoke from the bombing in the adjacent neighborhood covered our bodies and our bags.

It wasn't too long before the vicious bombing intensified in the area, targeting residential blocks in particular – I immediately thought of the bombing of the Taluli block in the camp late last October, which brought down an entire block in one instant, killing and wounding 400 people. So, my family moved to one of the shelter schools, just hundreds of meters away from the apartment we had first sought refuge in.

I will never forget that attack. It was the most terrifying thing I had experienced in my life. Bombs rained down around us in the dozens. We were sitting and staring at the ceiling as we waited for the next bomb to drop on us. What if that actually happened?

I will never forget the sight of that elderly man who survived the bombing. Most of the walls of his room were blown away, and his face was cut open. But he stood there watching us, with his cigarette lit. We try to defy death in any way, even with a cigarette, its smoke rivaling the smoke of the bomb.

I remember those moments in excruciating detail, how my father was gesturing at us with his eyes, to push some of us to go to the bedroom, while he gestured to others – with his steady hands despite the trembling that only a father like him would notice – to enter another room. As if the bomb, when it fell, would tear apart the ceiling over some of us but not others.

It was a day of horrors. I went out to search for the bombed area, only to find it just five hundred meters away from us. As I walked, I saw a paramedic trying to save a little girl inside an ambulance. There were two young men carrying a blanket wrapped around a body with no head. I started recording a video.

People were running, not knowing where to go. Dust and debris were still falling from the sky. A mother and her children were screaming. The mother called out and begged me, "My husband is under the rubble, get him out!" I looked at her daughter, who looked about 16 years old. She was crying but the shock of the event prevented her tears from falling. Blood covered the details in her eyes.

It was a day of horrors. I went out to search for the bombed area, only to find it just five hundred meters away from us. As I walked, I saw a paramedic trying to save a little girl inside an ambulance. There were two young men carrying a blanket wrapped around a body with no head. I started recording a video.

There was a young man distributing masks. There was no virus in the camp, only the smoke and fumes of death. I arrived at the destroyed block. When there's destruction, a person can see the wreckage, the rubble, the rocks. Thirty houses. I can't really say they were destroyed, but rather had disappeared under the sands they had been built on top of.

There was no trace of a single door, window, or ceiling. No picture frames, no notebooks, and no children's scribbles on the walls for survivors to stand on their remnants.

Do you know how the neighbors identified the location of the door of one of the houses when one of them heard the sound of a child under its rubble? One of them saw the electric wire of the water pump. The pump, in the camp, is always at the entrance of the house. This electric pump pushes the water to fill the water tank. I always imagined the water knocking on the walls of the tank when it heard the sound of the bomb falling from the warplane.

We started digging with our bare hands, while others removed rocks that had been blown from nearby houses.

There was a young man distributing masks. There was no virus in the camp, only the smoke and fumes of death. I arrived at the destroyed block. When there's destruction, a person can see the wreckage, the rubble, the rocks. Thirty houses. I can't really say they were destroyed, but rather had disappeared under the sands they had been built on top of.

I will never forget the sight of that elderly man who survived the bombing. Most of the walls of his room were blown away, and his face was cut open. But he stood there watching us, with his cigarette lit. We try to defy death in any way, even with a cigarette, its smoke rivaling the smoke of the bomb.

When I stood in the midst of the devastation, I couldn't tell if I was standing over a bedroom, a kitchen, or perhaps a clothesline. I felt like I was standing over souls still searching for their bodies that were snatched away as they slept.

I returned home to the camp, showing my mother and siblings pictures of the destruction. I was terrified and wanted my family to see what I had seen. This prompted everyone to head towards the nearby shelter school for refuge. We didn't have a classroom like the other families that had arrived before us. Instead, we divided ourselves among the neighbors. One of my brothers moved in with his wife's family, while the other decided to stay with relatives in another school.

I remember those moments in excruciating detail, how my father was gesturing at us with his eyes to push some of us to go to the bedroom, while he gestured to others to enter another room. As if the bomb, when it fell, would tear apart the ceiling over some of us but not others.

It was not just safety that was lacking. Since the UNRWA staff left Gaza, the conditions of displaced families worsened. There wasn't enough water or food for the children and their families. Sanitation was lacking in the bathrooms, and there were no nurses to tend to the sick. It was a catastrophe for all of us.

What does it mean for the residents of the north to flee their homes when we know that 70 percent of Gaza's population are refugees?

The harshest of all is the experience of living in a refugee tent inside the school.

Perhaps less harsh was setting up a refugee tent next to the rubble of your destroyed home.

Sometimes, I don't like to call it refuge or asylum. How can it be, when we're right next to our house?

*****

I remember the day when the sky poured black rain as it mixed with the dust from the bombings, the day the tents in the schoolyard where my family sought refuge were drenched. The children were running around in the schoolyard enjoying the water, while the new mattresses in the tents got wet.

What does it mean for the residents of the north to flee their homes when we know that 70% of Gaza's population are refugees? The harshest of all is the experience of living in a refugee tent inside the school. Perhaps less harsh was setting up a refugee tent next to the rubble of your destroyed home. Sometimes, I don't like to call it refuge or asylum. How can it be, when we're right next to our house?

On November 4, 2023, our names – my wife, our children, and I – appeared on the list of those approved to leave Gaza through the Rafah border crossing. Our son Mustafa holds American citizenship, so we were able to travel with him. Our journey south, towards the crossing, was delayed due to the danger on the roads.

But with the intensification of the bombing around us, we had no choice but to head south. I was heartbroken to leave my parents, my siblings, and their children behind.

I was also going to leave our destroyed home. I had always wanted the war to end so that I could return and salvage what I could of the books and clothes we had.

On the morning of November 19, my wife and I took our belongings and our children and headed south. There were no means of transportation, but we were fortunate to find a cart pulled by a donkey and driven by a boy. Our guide became the procession of families who had set out on foot before us. Little boys and girls carried white flags as they dragged their tired bodies among their family members.

Our only guide was the procession of families who had set out on foot before us. Little boys and girls carried white flags as they dragged their tired bodies among their family members.

The journey lasted about an hour until we reached the Kuwait Roundabout, where thousands of displaced people had gathered. Most of them were holding up their personal identification cards. I didn't understand the purpose of this. I followed suit and raised my ID card and American passport.

I could see dozens of soldiers to our left, aiming their rifles at us from behind a sand hill.

It was our turn to pass by the tank, which controlled the number of people crossing the road at a time, like a traffic officer.

We entered through a gate in the middle of Salah al-Din Road, and we heard the voice of an Israeli soldier speaking Arabic clearly: "Move slowly. One by one. Put down your ID. Just look in our direction."

I noticed he was calling out some people by describing their clothing and what they were carrying. It never occurred to me that he would call out to me, as my name and my family were on the list of travelers approved by Israel.

"The young man wearing a black jacket, with a black bag, carrying the boy with the red hair. Put down the boy and your belongings and come here."

That young man was me. I decided to approach carrying my three-year-old son towards the soldiers to clarify the situation, but the soldier shouted at me, "Put the boy and the bag down and come here and get down on your knees behind the other guys."

I was taken to an unknown location. Everything now is forever unknown. Perhaps there were ten of us in a tent somewhere. We sat for an unknown amount of time as the cold air tormented our bare bodies. The cannon behind us fired shells towards Gaza. Are my parents and family members okay in the north? Are my wife and children okay?

In the square, with the soldiers and the queue of displaced people, there were around two hundred people of all ages. A boy, perhaps 17 years old, asked me, "Do we read the ID number from right to left or the opposite?"

When it was my turn to read my ID number, the soldier ordered me to raise my hands and walk to the left, where a military jeep and three soldiers were waiting for me along with another young man. Two of the soldiers pointed their rifles at us, while the third soldier ordered us to take off our clothes. We remained in our underwear. Then he surprised us by asking us to take everything off and turn around.

Then the soldier asked us to put our clothes down and move towards two other soldiers who tied our hands behind our backs and blindfolded us with pieces of cloth before one of the soldiers dragged us to an unknown area.

Did my grandfather Hassan and my grandmother Khadra experience the same feeling when they looked back as they left Jaffa (Yafa)?

***

Everything is unknown now!

The soldier sat me in front of an Israeli officer who was going to interrogate me. I started speaking in English. I briefly talked about my life and what my daily routine was like on October 7th.

"You're a Hamas activist!" The officer threw this (figurative) bomb in front of my blindfolded eyes.

"I am not."

"We have information saying you are."

"Do you have proof? A photograph, video, satellite evidence?"

He punched me in the face.

"You're the one who will bring the evidence."

I won't forget the insults I was subjected to. I won't mention them here, of course.

We were thrown into a military vehicle. It started moving. Then it stopped. The intermittent sound of gunfire. Perhaps this is the end?

I was taken to an unknown location.

Everything now is forever unknown.

Perhaps there were ten of us in a tent somewhere. We sat for an unknown amount of time as the cold air tormented our stripped bodies.

The cannon behind us fired shells towards Gaza.

Are my parents and family members okay in the north?

Are my wife and children okay? Have they reached the south, or are they waiting for me just beyond the checkpoint?

We were thrown into a military vehicle. It started moving. Then it stopped.

The intermittent sound of gunfire.

Perhaps this is the end?

A soldier hits me from behind and orders me to lower my head. I'm blindfolded and my hands are tied.

The vehicle starts moving again.

The soldiers got us out of the vehicle after half an hour. I hear the sound of soldiers and female soldiers at a military site. Perhaps this is where the investigation will take place?

No.

A soldier kicks me in the stomach. I fly back, blindfolded and handcuffed, to the ground. My breath leaves my lungs for a couple of seconds. I didn't have a watch to count the time. I sit there, blindfolded.

A soldier pushes me to adjust my sitting position. He kicks me in the face. I am blindfolded. My nose bleeds. I am the unknown, the unidentified man on a land that my feet have never set foot on before today.

They throw us back into a military bus. I feel the rain seeping through the window.

After about two hours, the soldiers let us off the bus. We change our clothes and sleep on a very thin plastic sheet.

That was the end of the first day.

A soldier kicks me in the stomach. I fly back, blindfolded and handcuffed, to the ground. My breath leaves my lungs for a couple of seconds. I didn't have a watch to count the time. I sit there, blindfolded. A soldier pushes me to adjust my sitting position. He kicks me in the face. I am blindfolded. My nose bleeds. I am the unknown, the unidentified man on a land that my feet have never set foot on before today.

On the second day, I was interrogated in the evening. After leaving the interrogation room and before being transferred to the detention center with the others, a soldier surprised me by speaking to me in English, "We apologize for the mistake, you will go home."

I couldn't believe it. I felt like something was happening behind the scenes. On the third day, the soldier in charge called my name.

"What's your ID number?"

He stood with me at the door waiting for something I didn't know. Through the glass window, on the other side of the door, I could see two soldiers approaching, one holding a Palestinian identification card. I felt it was mine, while the other soldier placed a shirt in front of me to wear.

"You're released."

***

Then began the journey – the harshest one yet – back to the square. To Salah al-Din Road where I was abducted.

The soldiers only gave me my personal ID card.

It was the most brutal journey. The frantic search for my wife and children in Deir al-Balah. The journey to check on my large family in northern Gaza. Did I lose anyone?

I spent nearly two hours looking for my wife Maram and my children Yazan, Yafa, and Mustafa until a young man on the street directed me to the schools where the residents of Beit Lahia had evacuated, where Maram's uncles had preceded us weeks ago.

As we left Gaza. I looked back at the crossing gate that said, "Welcome to Palestine." Hundreds of images from Palestine, from Gaza, crossed my mind. The geography that is being erased every day. Did my grandparents look back too, as they left Jaffa (Yafa)? Does the dream of the Palestinian in Gaza still include the return to Jaffa (Yafa), Haifa, and Nazareth (Al-Nasirah), while dreaming of returning to a destroyed home? Who will promise the Palestinians a return to a homeland that has been stabbed a thousand times over?

When I reached the street overlooking the school, I met my daughter Yafa.

She yelled out in English, "Dad!"

Then she said in Arabic that her mother was looking for me.

Ten days later, we left Gaza. I looked back at the crossing gate that said, "Welcome to Palestine."

Hundreds of images from Palestine, from Gaza specifically, crossed my mind. The geography that is being erased every day. The cities where almost nothing remains except the names of their streets.

Did my grandfather Hassan and my grandmother Khadra experience the same feeling when they looked back as they left Jaffa (Yafa)?

Will families displaced towards the north be able to sneak across like the family of Mahmoud Darwish did from Lebanon to the Galilee?

Does the dream of the Palestinian in Gaza still include the return to Jaffa (Yafa), Haifa, and Nazareth (Al-Nasirah), while dreaming of returning to a destroyed home?

Who will promise the Palestinians, not a national homeland, but a return to a homeland that has been stabbed a thousand times over?

* The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!