As soon as Kemal (pseudonym) hears a police siren, the thin child trembles, rushes to slam open the front door of his house, and throws himself onto his mother's lap, weeping fearfully that the police will take him from his family. His mother, Alia (pseudonym), a Sudanese refugee in Egypt, is torn apart by pain – from the rape she suffered 14 years ago, and from the sadness she feels for her child, who is unable to prove his identity.

Alia lives in a state of constant fear that he could be taken away from her and, because she is unable to prove that she is his mother, does not let him leave home on his own.

According to The Egypt Response Plan for Refugees and Asylum-Seekers from Sub-Saharan Africa, Iraq & Yemen 2020, a report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Cairo with CARE International, the latest report covering this topic, there were 1,312 registered cases of sexual violence during the first ten months of 2019. Africans accounted for 90% of the survivors of these assaults.

Of all reported crimes involving sexual violence, rape is most common. Of the 142 cases of sexual violence – of which 89.4% involved women and girls and 10.6% men and boys during October 2019 – 85 (60.7%) of the total reported incidents were of rape.

This study reveals the failure of both the UNHCR in Egypt and the Ministry of Interior, represented by the police, to provide legal support to victims in establishing that rape had occurred, and in registering the resulting child victims of these incidents.

Multiple studies, investigations, and inquiries have reported sexual assault suffered by refugees in Egypt, but there is only sparse media information, with little detail, on the subsequent victims – those born as a result of such assaults.

Sexual violence haunts African refugee women in Egypt

Sexual violence haunts African refugee women in Egypt

Egypt does not send refugees to camps –as is the case in Jordan and Lebanon, for example– rather, it opens the doors for them to integrate into Egyptian society. The UNHCR is responsible for registering the migrants’ documents and determining their legal status, and they are all subject to the laws of the state.

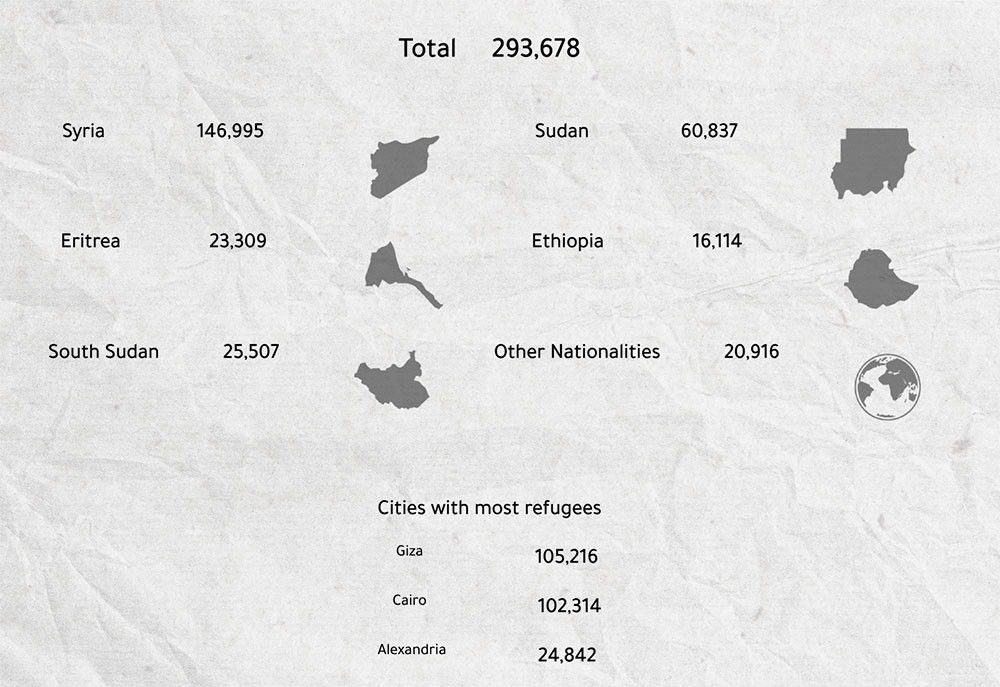

Despite the lack of accurate statistics on the number of refugees in Egypt, especially with the influx of those fleeing Sudan in its recent events, between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the Rapid Support Forces in April 2023, they have not yet been classified as immigrants, expatriates, or refugees. However, according to the periodic statistical report issued by UNHCR in April 2023, there are 293,678 refugees registered with UNHCR in Egypt, 50% of whom are Syrian, while Sudan and South Sudan rank second in terms of the percentage of refugees, followed by African countries such as Eritrea, Ethiopia and others. But there are no accurate figures on the number of women refugees in Egypt.

Alia sought refuge in Egypt with her family in 2005, after leaving Sudan to seek protection for herself and her two children from the war, and to provide them with a secure life. After the crisis in Darfur, she fled to the city of Nyala where she lived in a tent. But she found the living conditions unbearable and filled with danger that she saw women being raped in front of her. So she decided to move with her children to Egypt. But Alia had no idea what fate would have in store for her, just four years after she sought refuge in Egypt. In 2009, two men she did not know kidnapped her for a year and a half, during which she was repeatedly raped and, as a result, became pregnant with Kemal. She gave birth in Egypt and, as a result, the boy was unable to acquire any identification papers.

Countries and cities with the highest number of refugees

Countries and cities with the highest number of refugees

Gender-based violence

Gender-based violence is widespread in Egypt, particularly crimes involving sexual violence, like harassment and rape. Such crimes have become so normalized in Egyptian social culture that the victim is normally blamed and stigmatized, with society seeking to justify the perpetrator’s act, accompanied by the legal loopholes that undermine the rights of the victim.

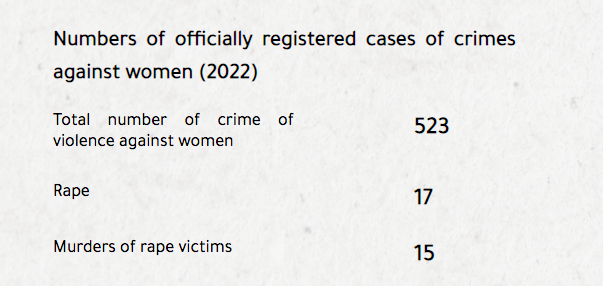

Number of officially registered cases of crimes against women (2022)

Number of officially registered cases of crimes against women (2022)

The Violent Gender-Based Crimes Observatory, which is part of the Edraak Foundation for Development & Equality, has recorded 523 officially registered crimes of violence against women, of which 17 involved rape. The real number is probably much higher, because victims – particularly victims of sexual violence - are fearful of reporting it and pursuing the legal route.

Figures and statistics on crimes of violence against women and girls in Egypt for the year 2022 – semi-annual report

Figures and statistics on crimes of violence against women and girls in Egypt for the year 2022 – semi-annual report

Refugee women suffer alongside Egyptian women, especially given their precarious situation and poor living conditions, which mean they often have to live in dangerous slum areas, or accept work that puts them at greater risk of rape.

When Alia showed signs of going into labor, she felt like the pain was tearing her apart. Her two kidnappers pushed her into a car and took her to the ‘6th of October Hospital’ in Giza Governorate. But the hospital refused to admit her in the absence of her husband or any identity papers, so the two men left her to suffer on a chair outside the hospital and fled. “When my pain reached its peak, I just gave birth on the ground,” says Alia sorrowfully.

Alia (audio transcription): "They took me to the 6th of October hospital, and told me that there was no one other than the reception staff at the hospital. Then they seated me outside the hospital and told me that they were going to bring my husband and come back, but they went and never returned. My pain intensified while I was outside the hospital after they deceived me, when they told me that the hospital would not admit me without my husband. After that, my fetus fell to the ground, and they kept asking me, 'Who brought you here?' but I didn't know them."

Given her psychological trauma, Alia doesn't remember much of her birth ordeal, but she remembers hospital staff insisting on knowing who was coming to take her home. After they had tried to contact her husband (who had been looking for his wife) they issued a notification of the child’s birth in his name, but he later denied being the father.

Alia (audio transcription):

Journalist: What did your husband do when he came to the hospital?

Alia: My husband claimed me because he was embarrassed in front of people.

Journalist: Does that mean the child was registered under your husband's name?

Alia: Yes, and after four days of giving birth, I went to the civil registry, and they asked me to close the report, saying they would follow up later. Then we went to the "Saint Andrew" institution with the hospital documents.

Journalist: What is the fate of the report?

Alia: Nothing. They asked my husband to register the child under his name, but he refused, considering the baby an illegitimate child.

Her husband threatened to kill Alia and the boy to “avenge his honor”, forcing her to flee with the child. She later went to the UNHCR and met one of the lawyers, the organization promised to follow up her case.

Four days later, Alia accompanied one of the Commission’s lawyers to prepare a report on the incident, after her husband refused to register the child in his name, but then the lawyer traveled after a while, and Alia does not know the fate of that report. Thirteen years after Kamal's birth, he has yet to obtain a birth certificate.

On 19th October 2021, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the UN Commission on the Rights of the Child issued the first report on babies born to victims of rape: “Armed Conflict: the Second Victim of the Crime.” The report showed that, because the mother has no right to register her child, it is deprived of citizenship and consequently of all its rights.

Because Alia wasn't able to register Kemal, he was deprived of neonatal healthcare and of childhood immunizations, which the state provides equally to both Egyptian and refugee children. Alia could not afford to pay for him to be immunized at a private hospital, and lived for years in fear that he would contract one of the diseases that other children are protected against.

“The fact that his skin is a different color creates problems with the neighbors and at his own house. My youngest son is always telling him ‘You’re white’, ‘You’re an Egyptian peasant’. Kemal’s light-coloured skin means his brothers discriminate against him and he’s an object of curiosity and suspicion outside the house,” says Alia. So she is forced to hide her child at home and stop him from going out, even if she or his brother is with him, in case a neighbor reports her, or a security officer, who usually patrol the streets of Egyptian cities, should suspect her.

“The worst thing is what was written in the child’s birth certificate, stating that he is illegitimate, born of adultery.” Maryam was angry because she has medical reports proving that the child was conceived as a result of rape, not sex outside marriage.

For the last 13 years, Alia has paid almost daily visits to the UNHCR office to ask for legal help to register her child, in order to safeguard his future by establishing his existence. All her requests have been met, however, with procrastination. “Up until last year I’ve been trying with the Commission to get my child registered, but they either say they don’t have a lawyer now, or that the lawyer on my case has left, and they will look for another one, or they just say, ‘Go home and we’ll be in touch later,’” she says.

On paper, Kemal does not exist in the eyes of the Egyptian state, nor with the UNHCR. Subsequently, he has no right to education, which forced Alia to enroll him unofficially in a private school and pay all his expenses, which amounts to approximately $350. This sum is beyond her means, as she either carries out domestic work or organizes henna parties for brides and earns a daily wage of no more than $10.

Moreover, her son is a “ghost” pupil at the school, and cannot sit any class exams alongside his peers, because his name is not on the official roll.

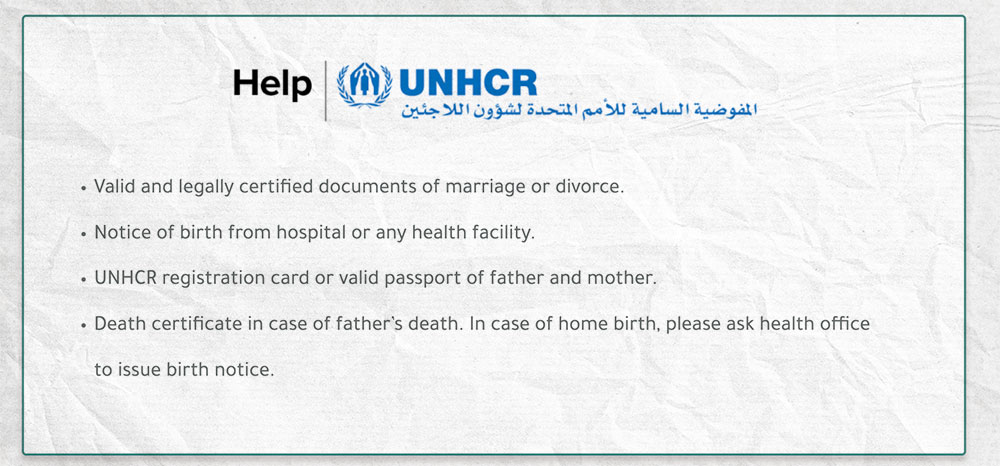

According to UNHCR conditions, a birth certificate proving the child’s existence and naming his parents is needed for him to obtain a refugee card. Kemal is therefore not eligible for services provided by UNHCR, whether they be paying part of the school fees, providing monthly aid, or even being given clothing. Nor can he take part in most of the activities organized by UNHCR’s support organizations for children, as he has no papers to prove who he is.

UNHCR required documents for birth certificates for newborns

UNHCR required documents for birth certificates for newborns

A psychologist at an institution partnering with the UNHCR (who asked to remain anonymous) says that she sometimes asks Kemal’s mother to bring him along and let him take part in some of their activities out of generosity, so as to ease the psychological burden of him feeling different from all the other children in his community. The same thing is usually done with cases like Kemal’s, though this is against the institution’s internal regulations. And they cannot include him in the main events, which require the identities of the participating children and their families.

Clear but ineffective legal measures

This delay and procrastination occur, even though Article 6 of Egypt’s Child Law No. 126 of 2008, states that “every child has the right to acquire nationality in accordance with Egyptian nationality law.”

Texts and articles of the Child Law in Egypt and the latest updates and amendments - Article 6

Texts and articles of the Child Law in Egypt and the latest updates and amendments - Article 6

Furthermore, Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Egypt signed in 1990, also stipulates the right of the child to be registered at birth, to acquire nationality and – as far as possible – to know its parents. States who are party to the Convention are obligated to ensure application of these rights, in accordance with their national law.

Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 - Article 7

Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989 - Article 7

A victim of lack of trust

Kemal is not the only child to be denied official registration in Egypt. Four-month-old Waad (pseudonym) is another case, who suffers the same problem over “color” and other issues.

Waad is also a victim of the criminal kidnapping and rape her mother suffered. In 2022, Sudanese refugee Maryam (pseudonym) was forced to leave her home on the first day of Eid al-Fitr. Because she works doing henna designs and domestic cleaning, she could not afford to rent a house temporarily, so was forced to sleep in a public garden with her four children.

A woman lured her, claiming to have a house where Maryam could stay in return for doing domestic chores. Maryam trusted her as a woman like her who would do her no harm. But there she was kidnapped with her children and subjected to repeated rape. A few days later she was able to escape with her four children, while the fifth was already growing in her womb.

This was not the first time Maryam had been raped. Six years before this incident, when she was newly arrived in Egypt, she was raped by a property agent, when she was looking for somewhere she and her children could live in. When she went to see a property, he attacked and raped her in front of her children. Three months later she realized she was pregnant.

Interview with African Sudanese refugee assaulted in Egypt - Audio Soundbite transcription translated

Interview with African Sudanese refugee assaulted in Egypt - Audio Soundbite transcription translated

Maryam (audio transcription): "Since I came to Cairo, and in the first days of trying to find an apartment for rent, the real estate agent said there was an apartment in 'Azbet El-Nakhl.' I went with my children, and as soon as we entered the apartment, I was attacked/raped and beaten.. I couldn't go to the police station because I didn't even know his name. There was a woman cleaning the stairs, but she was afraid to help me. She only opened the door for me and let me escape."

Difficulties at the police station

The Egyptian police lack gender-sensitive procedures and sympathetic ways of handling crimes of a sexual violence nature, and despite there being plenty of images of female police officers patrolling the streets during holidays, there are rarely any female police officers in police stations.

Maryam headed straight to the police department in Dokki, after she saw the perpetrator in the area the department covers. She tried to file a police report, but her complaint was met with skepticism. She tried to prove the truth of her claims, but was subjected to harassment by police officers, who refused to draft the police report until they had the full, three-part-name of the perpetrator.

“I tried to convince them that I knew the café where the perpetrator used to go, but they refused to help me write a police report,” Maryam says.

Interview with African Sudanese refugee assaulted in Egypt - Audio Soundbite transcription translated

Interview with African Sudanese refugee assaulted in Egypt - Audio Soundbite transcription translated

Maryam (audio transcription):

"Journalist: Did you know which police station was affiliated with the place?

Maryam: The Sudanese later told me it was Dokki Police Station... I didn't know initially.

Journalist: Did they refuse to file the report?

Maryam: They flat out refused, saying I must provide his full name, but all I know about him is that people call him "Rida."

Journalist: Did you know his whereabouts?

Maryam: Yes, I told them I know the location of the café he frequents. He took me from downtown and kept convincing me that the apartment was close to the place, but it was in 'Azbet El-Nakhl,' which is a considerable distance away.

Maryam went to the commission, which appointed a lawyer for her to help her register Muhannad (the child resulting from rape), and after several months of attempts to register him officially and legally, they ended up registering him with the help of a lawyer, and his lineage was traced back to the mother’s grandfather. Maryam felt that she had achieved an accomplishment, especially after she was able to get rid of her anger towards the child, and began having affectionate feelings for him. But soon things changed again. In the birth certificate, the marriage contract area said “an adulterine child”, carrying an eternal stamp that will continue to haunt her and her child, reminding her of what she suffered, and stigmatizing her child forever.

“The worst thing is what was written in the child’s birth certificate, stating that he is illegitimate, born of adultery.” Maryam was angry because she has medical reports proving that the child was conceived as a result of rape, not sex outside marriage.

Interview with African Sudanese refugee assaulted in Egypt - Audio Soundbite transcription translated

Interview with African Sudanese refugee assaulted in Egypt - Audio Soundbite transcription translated

Maryam (audio transcription): "The unfortunate thing at the police station is that they labeled my son as adulterine child and not a rape victim, and this saddened me deeply."

Maryam could not bring herself to go back to the police station to correct what was wrongly written in the report, and to present medical reports proving the rape. She was afraid she might again have to face the contempt and insults she faced before, and accusations of indulging in illicit relationships.

“If you go to the police, they will insult you and say rude things... They’re not polite… not respectful. They use bad words... very bad”

The police were not the only ones who let Maryam down and accused her of working in the sex industry. She faced the same accusation from one of the doctors at the El Shatby University Hospital in Alexandria, because the prevailing belief is that refugees make up sexual assault claims to speed up the process of resettling them in European countries.

In a despairing tone, Maryam says, “When I was seven months pregnant, the doctor at the El Shatby General Hospital in Alexandria refused to help me unless my husband was present. I told him my husband was not around, but he accused me of working as a prostitute. I explained what had happened to me, and the pain I was in and that I had medical reports. But he refused to help me.”

The police department again refused to file a report about her case, and asked her to bring a notification from UNHCR, and a lawyer so they could draft a report establishing that the incident had taken place. She had no option but to turn to the UNHCR for legal support. But the UNHCR refused to take responsibility and asked her to go back to the police department. Up to the date this report is published, the UNHCR has done nothing to help Maryam prove her child parentage.

But most refugees do not know

Ashraf Milad, a lawyer specializing in refugee cases, says, “If the police department refuses to draft a report to confirm what has happened, the lawyer representing the victim has the right to go to the public prosecutor to get them to write to the police department involved and force them to draft a report on the incident.”

Police officers are part of the Egyptian society, and are for the most part influenced by the culture of the society in their handling of victims of sexual assault, treating women’s claims with suspicion or blaming them.

Ashraf says: “Sometimes the approach of police stations is to not file reports confirming incidents of rape because they believe most victims are lying. There are rumors about the existence of directives related to reducing the number of reports of assaults on male and female refugees."

“A report on an incident of rape is not a pre-condition for establishing the resulting birth, because it is extremely difficult to conclusively prove the rape has taken place – even though it could be punishable by death. Sometimes the rape follows a kidnapping in some unfamiliar place, or the victim may know nothing of the perpetrator. In this case, a report is kept, and that is sufficient to establish officially that the victim is pregnant, and that she is the child’s mother. The birth is then registered in the health office in the normal way.”

Ashraf points out that the role of UNHCR is to refer the case to one of the lawyers in the legal team of the organizations it works with, because the UNHCR is the sole body that can take forward measures affecting the community of refugees.

“When I was 7 months pregnant, the doctor at El Shatby Hospital in Alexandria refused to help me unless my husband was present, accusing me of working as a prostitute. I explained what had happened to me, and that I had medical reports. But he refused to help”

Muhannad was more fortunate than his sister Waad. Even though he missed out on neonatal immunisations, he was still able to enroll at school and has an official birth certificate confirming his right to life. As for Waad, however, her mother is still trying, through the police and the UNHCR, to register her and establish that she is Waad’s mother.

A birth certificate – whatever the nationality – is the only way to prove that a child exists, and it allows for other official documents to be issued.

A “miracle” suspended

On paper, seven-month-old Mu’jiza ['miracle' in Arabic] (pseudonym) has two parents. But officially she is not registered as a living person. Although her mother obtained a fake marriage certificate, the little girl is living her first year without identification papers.

Etab (pseudonym) is a refugee from South Sudan. She began her story by telling us that she had tried to take her own life and that of her unborn child, after a Sudanese contractor of domestic workers kidnapped and raped her over a period of three days. She eventually managed to escape the apartment where she was held with the help of the landlord.

She subsequently showed signs of being pregnant and immediately approached the UNHCR for legal assistance and help in drafting a report. But the UNHCR asked her to find out the full name of the perpetrator, as he went by a nickname. She subsequently began to receive phone calls from him threatening her not to file a report.

Etab, barely 23 years old, could not cope with the responsibility of having another child, while also looking after her blind mother and the two children of her deceased sister. So she tried to abort the pregnancy herself, but was saved at the last moment. This time the UNHCR – through their partner organization CARE International– placed her in a psychiatric facility to receive treatment up to the time she gave birth.

“It is a miracle, she came despite all that’s going on around her, and despite me trying to abort her and commit suicide, and despite my bad health and unstable pregnancy, which meant I could have miscarried… despite my attempts to get rid of her, she clung to me.” Once Etab had gotten over the shock, she developed maternal feelings towards her daughter.

Etab (audio transcription): "We named her after what happened to her. I tried to abort her in various ways, but she insisted on coming. Once, I even swallowed pills to get rid of her."

Even though she knew all about the man who had raped her – as he was well known in the Sudanese community – Etab felt unable to report him, after hearing the experiences of other survivors, and particularly in view of the UNHCR being so slow in offering legal help and protection to these women. She opted instead for a traditional solution, and her mother interceded with the Council of Sultans (a traditional council of the South Sudan community in Egypt) to find a man who would be willing to become the father of the child. She did in fact find a man in her tribe who agreed to be registered as the father of the child.

The volunteer father, however, had accumulated a large debt from his university fees, £700 sterling pounds, which he could not pay. The university therefore refused to give him his official papers so he could renew his passport (the proof of identity under Egyptian law) and register the child. He asked Etab to pay off his debts, but she could not afford to pay the full amount. She approached all the aid agencies, but they did not give her the money she needed. Over time, her situation has become more difficult. She is now considering returning home or traveling to another country. But she cannot travel with a child unless she obtains a birth certificate.

“My baby and I could have been killed. Now I just want to close my file with the UNHCR and go back to my country. I'd rather die of hunger there, but at least I will not die here in another assault or lose my daughter.”

Etab is afraid to take her daughter out into the street, as she is haunted by the feeling that people will know that she does not have an official birth certificate for her daughter Mu’jiza and that they could separate them. She was once even physically assaulted. A passerby tried to verbally insult her and when she yelled at him, he threw fireworks at her, which got inside her clothes and caused superficial burns. Etab did not exercise her right to complain to the police, for fear that they would ask her for the child’s papers. She says in a painful tone, “We could have been killed… My baby was with me. Now I just want to close my file with the UNHCR and go back to my country. I'd rather die of hunger there, but at least I will not die here in an incident or lose my daughter.”

As of yet, the UNHCR hasn't published any statistics on the number of confirmed rape crimes it has on its books, or the number of children resulting from rape. Nor has it made any reference to this issue in its reports.

The author of the investigation sent several emails to the UNHCR press office and to CARE International requesting information on the number of complaints registered with them. The UNHCR responded by explaining its position on registering child victims of rape. She also contacted the Ministry of Interior, to clarify how African women victims of rape were treated in police stations. But up to the time this investigation was published, she had received no response.

This report was done in cooperation with ARIJ

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!