A woman living in the town of Idna noticed that her breasts were getting tender and swollen and began finding spots of blood in her underwear, but was ignorant of the significance of these signs. One day, she was encouraged to go to a breast cancer awareness campaign in her hometown of Hebron in the West Bank.

The secretary of the Higher Education institute in the town, Hind al-Tamezi, recounts the woman's story by saying, “We found out that she had breast cancer, along with 15 other women who had come to that campaign. I was shocked. I am sure that these diseases have spread due to ignorance and because of the burning of 'taqsh' (plastic-coated copper wires and electronic waste).”

The people of the Palestinian towns of Idna, Beit Awwa, Deir Sammit, and al-Kum have always relied on agriculture for their livelihood, but the construction of the apartheid wall on their lands in 2002 left them economically besieged. So they abandoned work on the land and unemployment spread among them, which exacerbated the number of those working in 'taqsh' without thinking about the dire environmental consequences that have hit the region, which al-Tamezi describes as bleak to this day.

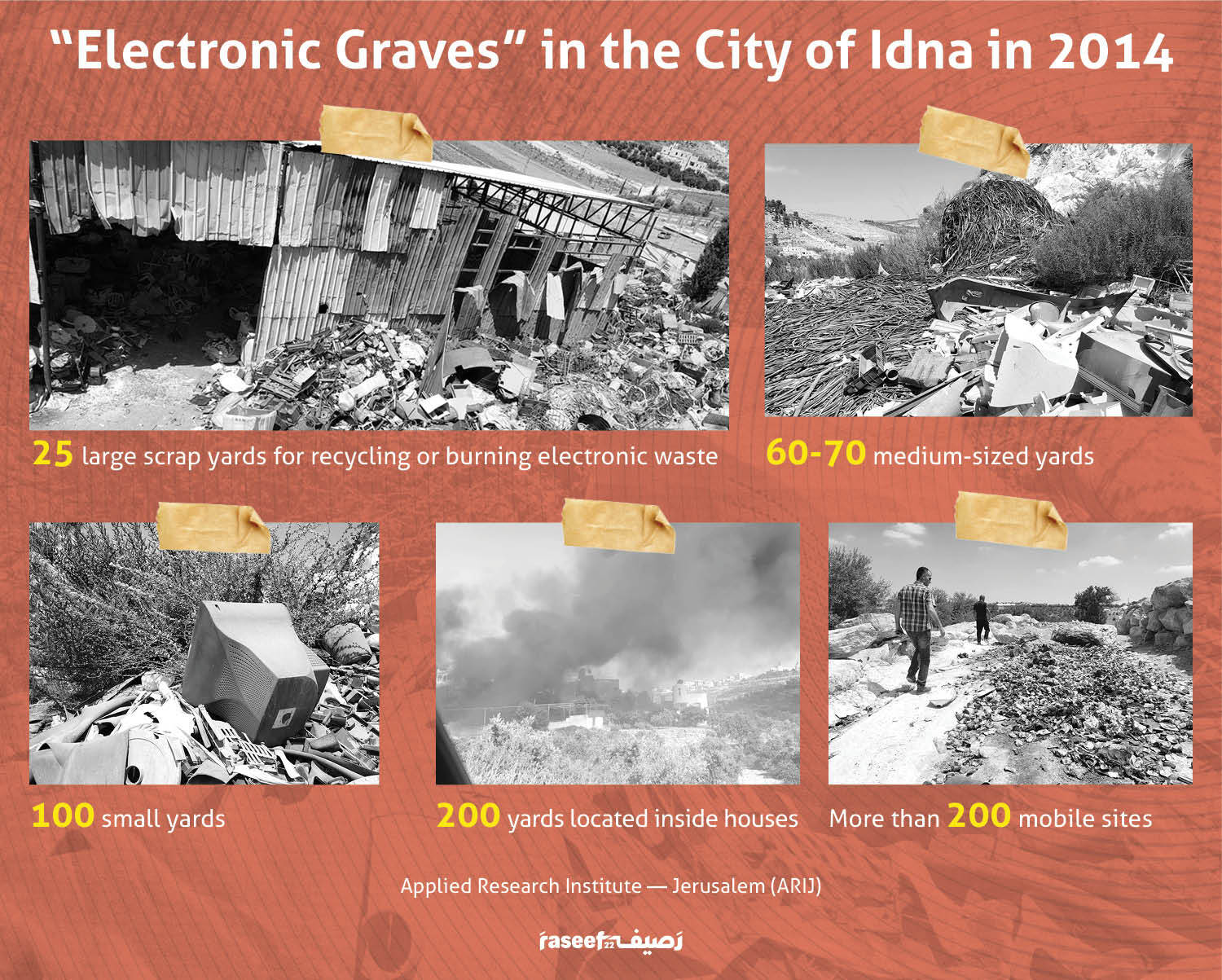

This photo and photos of subsequent fires are of the burning of electronic waste and copper cables, in the town of Idna in the Hebron district.

Those towns are pollution hotspots, with electronic scrap that come from factories, construction workshops, and home renovations in Israeli settlements. Its collection and supply are controlled by “Israeli and Palestinian mafias that enter it through the 'Tarqumiya' military checkpoint to these towns, which are essentially outside the control of the Palestinian authorities, as they are classified within Area C”, according to the mayor of Idna, Jaber al-Tamezi.

Area C constitutes 60% of the occupied West Bank, but Israel controls all aspects of life there, instead of the Palestinian Authority, according to the Oslo II Accord (aka the Second Oslo Agreement).

This report extends on the ground, to include the towns of Beit Awwa and Deir Sammit, and includes working women and housewives talking of their physical and psychological suffering with the daily burning of copper and plastic wiring along with all kinds of other scrap: refrigerators, washing machines, computers, etc. This has prompted some of them to leave for other areas in search of a clean environment.

On the other side of the Mediterranean, in Tunisia, 40-year-old Reem daringly searches with exposed hands for plastic inside garbage containers in the makeshift dumps that appeared in the capital Tunis following the 2011 revolution, in order to make a small amount of money to feed her family for the day.

Reem lives with her husband and two children, one of whom is autistic, in a house that lacks the most basic necessities of life, in a popular neighborhood where garbage and random dumps have piled up west of the capital.

These women, known as 'barbechas' (waste collectors who sort plastic from garbage and makeshift waste dumps) in Tunisia, share the same social and health plight as that of the Palestinian women of western Hebron, due to political and economic conditions they have no control over. They are unjustly affected by diseases from waste residue, in the face of official and social neglect and silence.

As if this was not enough, Reem has been competing for four years with other 'barbechas' to make a living; some use heavy carts to collect the largest possible amount of plastic, thus reducing Reem’s chances. There are thousands of men doing the work too, with rising unemployment rates due to the Covid-19 epidemic reaching 16.1% in 2022, according to the Tunisian National Institute of Statistics.

Blackened hands searching for food

Reem is not the only one. Lamia, Jamila, Haniyyah, and Souad also work in landfills and are beset by compound gender injustice. Haniyyah, 60, resorted to collecting plastic bottles after her children neglected her and her diseases multiplied. The streets of the southern suburbs of Tunis are a way for her to ensure her daily food.

Lamia, a mother of four, is perhaps a little more fortunate than the other women we met, as she collects plastic bottles set aside for her by the residents of her neighborhood. Despite this, the financial return remains small.

The same injustice applies to the women of the western towns of the West Bank in Palestine. The men have specialized in the trade and burning of 'taqsh' due to the complete absence of development projects in the area, making it the main financial resource for most local families, along with the 'zakhm' (used furniture) trade, a profession that the people of Beit Awwa has been practicing for the last fifty years.

As the women of 'barbecha' in Tunisia continue to work silently without masks, gloves, or any other means of protection, Palestinian women continue to work in 'taqsh' in "family workshops without protection and with tools that may cause death or mutilation"

In both countries, the authorities have not yet enacted laws that include environmental rights advocating or protecting women, even though Tunisia and Palestine are located on the Mediterranean, one of the regions most affected by climate change.

The average temperature is expected to rise by 2.2 degrees Celsius by 2040, according to a report by the Mediterranean Network of Experts on Climate and Environmental Change (MedECC). MedECC is an open, independent, and international network of 600 scientific experts from 35 countries that provides support and data to decision-makers and the public on the basis of sound scientific information.

These women, whether they live in popular neighborhoods in Tunisia or belong to economically and socially poor clans in Palestine, wonder about the role of the authorities in providing their most basic rights to social and health security that should guarantee them a decent life — one not spent digging through the garbage and suffering social stigma, or burning 'taqsh', polluting the environment, and harming people’s health.

Despite the environmental legislations, laws, and agreements enacted or adopted by Palestine and Tunisia, and despite the imposition of sanctions in this sector, the women of the 'barbecha' continue to work without masks, gloves, or any other means of protection. And Palestinian women continue to work in family 'taqsh' workshops “without protection and with tools that may cause disfigurement or death”, according to environmental and community activist Amina al-Batran. This work makes them vulnerable to heavy and radioactive elements such as lead and chromium, and to compound toxic gases such as dioxin, sulfur oxide, and carbon during burning, causing cancer and other diseases, as well as reproductive issues such as fetal abnormalities and miscarriage.

It is noteworthy that the relationship between these diseases and their causes has not been verified or proven, as the region lacks accurate scientific, health, and environmental studies by the Palestinian Ministry of Health and the Environmental Quality Authority.

'Tabarbish' and 'taqsh': Two worlds with their own special rules

In a dilapidated room behind her house, Reem stores her daily plastic harvest and then sells it at a collection point for 700-900 Tunisian millimes ($0.3 US dollars). In contrast to this pittance, the sale of copper extracted from burning 'taqsh' is linked to the global stock market. “The price of one kilo reaches nearly 37 shekels, or $11.38 dollars, while a ton of iron and lead reaches up to 1,400 shekels, or $430 dollars,” says the former mayor of the town of Beit Awwa, Abdallah Suwaiti.

"We don't know where these new smelly and transparent fumes are coming from. A neighbor or someone may be burning things next to your house, but it's difficult to determine its source after mixing in certain substances that turn the smoke transparent"

It has been necessary for workers to impose their own rules. The world of these professions, despite their marginality, is in fact governed by special laws. The 'barbechas' divide up the residential neighborhoods, containers, and landfills amongst themselves; Reem and a few others share the garbage containers with other 'barbechas' to ensure their place without any competition or intruders. Priority access to the place containing the garbage is a key 'barbecha' law.

Women are prompted by their social circumstances – such as having to support a husband, divorce, or poverty – to take up this work. Jamila, a 50-year-old woman whose husband was injured on a construction site that left him unable to work, covers the expenses of treatment, food, and rent by collecting plastic.

As for the world of 'taqsh', it is a complex one, in which there are no strict laws or deterrents. Sudden fires with pungent odors occur in unusual places, causing intoxicating smoke and suffocation. And even though the town’s anti- scrap committee — consisting of 13 members, and formed by the civil and security institutions of Idna in order to find radical solutions to combat 'taqsh' and find alternative solutions — hastens to extinguish them, they leave blackened areas in their wake with long-term effects.

Simply staying a few days in Idna reveals the extent to which this trade has invaded people's daily lives. Large open workshops next to each other burn, grind, and sort all forms of waste, private cars transport it without anyone stopping them, and agricultural land is polluted and poisoned by the effects of scrap burning.

The mayor of Idna, Jaber al-Tamezi, who has been active in the committee formed to combat scrap burning for eight years, describes the fires developing “gradually in agricultural lands near the separation wall, then between homes, and then large workshops, at an amount equivalent to 30 tons per day". He goes on to stress that, scrap "burning has turned into a worrying phenomenon that no one is able to combat, through which a group of individuals have made huge financial gains in exchange for polluting the air, water, and soil, as well as threatening livestock and the lives of the population with diseases that we have not seen before.” He then pauses and adds, “Everyone here knows that Idna has the highest cancer rates in the Hebron region.”

The big 'taqashin' (people who work in 'taqsh' burning) are called "mafias and gangs" in the region. They find ways to deceive and circumvent the customs police, and they deceive environmental agencies by burning near the apartheid wall, where these security agencies cannot intervene and arrest them, as stated by representatives of these agencies during a meeting with the mayors of Idna, al-Kum, and Deir Sammit held on August 15, 2022 that we attended during the preparation of this report.

Al-Tamezi explains, “The scrap is distributed to intermediaries, workers, and individuals who work alone in the burning process, in an attempt to thwart efforts to arrest them.” The enforcement of the Palestinian Environmental Law (1999) and the Hazardous Waste Management System Law No. (6) of 2021 is hampered in Idna and other towns, as a result of their security subordination to the ‘Israeli side’.

The council members of al-Kum village spoke of a new type of scrap burning. Council member Radhi Rajoub says, “We do not know the source of this new type of fumes. It is transparent and has a pungent smell. A neighbor or someone else might be burning next to your house, but it is difficult to determine the source of the smoke after mixing in certain substances that turn the smoke transparent.”

Most families who resort to 'taqsh' do so because of the ease of working in this illegal field. Despite attempts by the Palestinian Environmental Quality Authority to implement the international Basel Convention (which came into force in 1992 and aims to protect human health and protect the quality of the environment from hazardous waste, as well as treat it and regulate its transportation across borders) in the region, its efforts are “ineffective”, says Talib Hamid, Director of the Environmental Quality Authority in Hebron.

Hamid says, “We are in a real battle with the people and their source of livelihood, but we are trying to allocate work projects for the process of peeling copper wires coated with plastic, instead of burning them.”

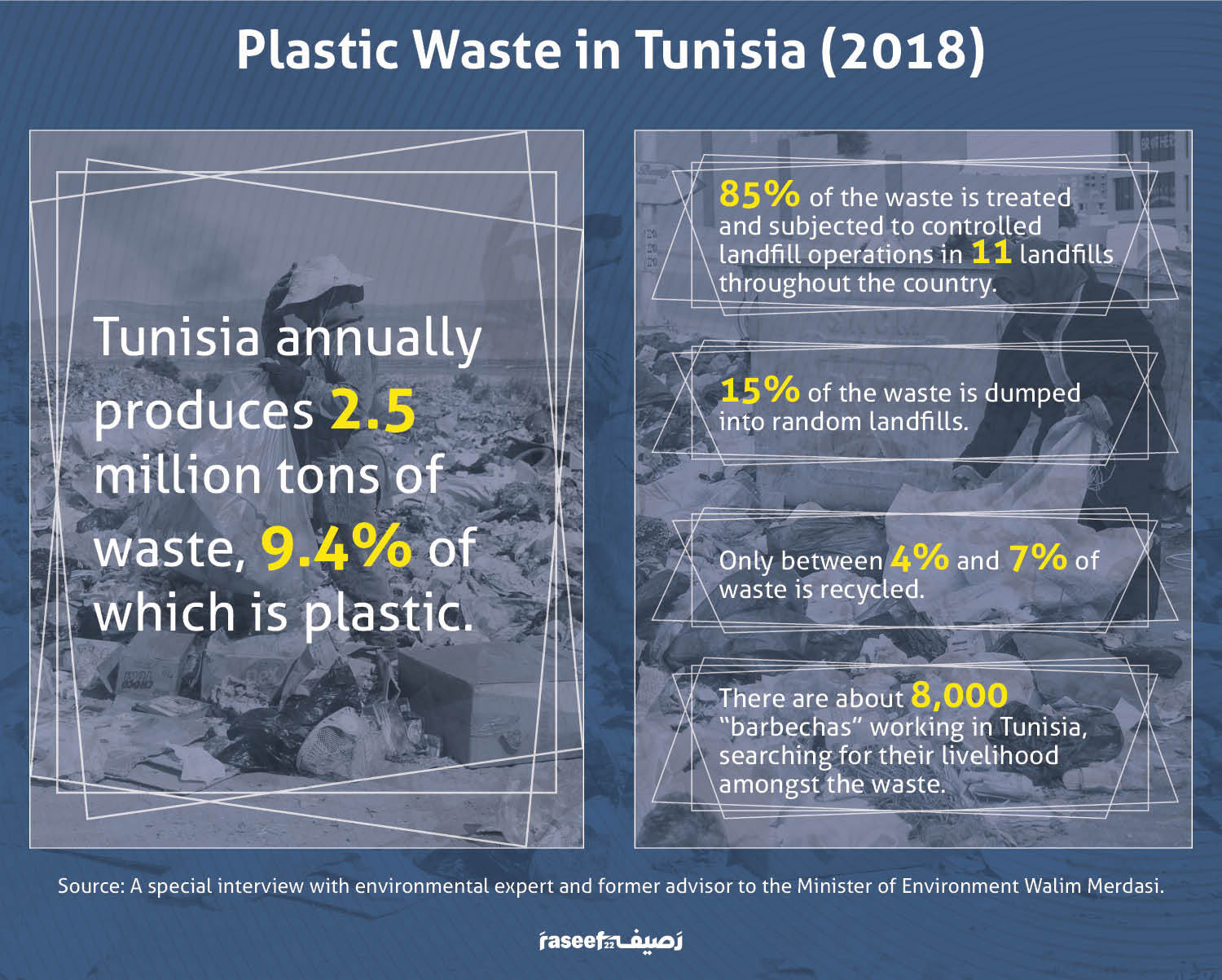

On the other hand, in Tunisia, thousands resort to sorting plastic waste due to the high consumption of mineral water bottles. Tunisia produces up to 2.7 billion plastic water bottles annually, according to the National Office for Mineral Water and Water Treatment.

The profession of sorting plastic waste expanded in Tunisia as an “economic activity at the beginning of the third millennium, after the policies of individual economic initiatives were encouraged”, says researcher Jihad Hajj Salem. He explains that this “created fragile popular classes that lack educational or material capital, that fell victim to these policies and work in fragile professions such as 'barbechas' in big cities, where the state implicitly encourages these professions and gives them flexibility to informally carry out their irregular activities.. These groups eventually adapt to the reality of the state’s withdrawal and its inability to provide job opportunities.”

Women looking for sustainable health and environment

The black fumes and the deadly smell made 55-year-old school teacher Maysoon Suwaiti, from the town of Beit Awwa, feel uneasy and unsafe. She says, “I was coughing like I was a chainsmoker, but I did not remain silent. I defended my right in life with all the strength I had. I spoke to our neighbor who was involved in the burning (of cables), and when he did not stop, we filed a case against him in court. They forced him to stop, but he went back to burning cables after a while. I began documenting, with my phone camera, every fire that was taking place as I passed through the streets of the town, and then I'd post the videos on Facebook to raise awareness, especially since academic researchers visited our area and we spoke of the dangers that threaten our existence in Beit Awwa. The air is polluted, and so is the soil, the water, and the food, but money is the most important thing for everyone, so I decided to leave with my family to the nearby town of Dura, where we currently live.”

Maysoon appealed to the ministries of Health and Environment but got no answer. She says that, before leaving, she “personally counted 70 patients in our neighborhood with various diseases." Even though the fires in Beit Awwa are on the verge of extinction, she and her family absolutely refuse to return.

Women in Palestinian towns face an unknown fate when it comes to their health due to the scarcity of medical seminars and awareness campaigns related to the dangers and effects of scrap burning. Activist Hind al-Tamezi describes the situation by saying, “We are oppressed and suffer socially, economically, and health-wise because of our lack of organization and the control of the unsustainable projects of the NGOs over our women’s associations. We lack intellectually qualified women to lead environmental awareness campaigns, due to the system of clan relations and traditions that restrict women, as well as looking at the issue of the environment as if there's no result from it.”

Women have not backed down, but rather they have tried to create change themselves by searching for sustainable solutions. Some of them joined the committee formed to combat scrap burning. One such person is community activist Amina al-Batran, whose neighbors tried to silence her complaints when she documented the fires after becoming seriously ill with sinus disease.

The sorting of plastic waste expanded in Tunisia as an “economic activity after the policies of individual economic initiatives were encouraged”, which “created fragile popular classes lacking educational or material capital that fell victim to these policies"

Al-Batran describes the phenomenon of burning as a “socially sensitive” one. Despite this, she joined the committee with the aim of preserving her country, “I stand with what's right. I take care of my disabled child, whose weak lungs are directly affected by any sort of smoke.” She adds, "Everyone prefers to cover up the burning and the 'taqsh', and do not report them. Women are afraid to get involved in the fight against burning scrap. I am the only woman in the committee so far."

Al-Batran continues her journey of recording and archiving the daily burning in the nine workshops surrounding her house, and in other places. However the results are “disappointing”, according to her, since the 'taqsh' burning has not stopped.

The secretary of Beit Awwa Elementary School, Ghada Suwaiti, describes how the backyard of the town's school is covered by black soot due to the burning. She says, “Smoke particles settle on the surfaces of benches, chairs, and everything else, and nothing prevents them from reaching the food and bodies of the students. In some cases we have to send the students home because of the intensity of the fires and the heavy air pollution.”

The effect of the 'taqsh' burning can be even viewed from space on Google Earth, appearing as large black spots staining the earth. This reflects the severity of the danger and the toxic environment in the region.

Environmental researcher John-Michael Davis, from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA, has lived with the problem of burning 'taqsh' for nearly ten years in those villages. He has previously participated in published studies, including one published in the International Journal of Cancer (IJC) in 2018, which indicated “the high risk of childhood cancer lymphoma, at a rate four times the average, at sites where scrap-burning is active" in those towns.

“Lymphoma is just one type of cancer,” Davis says in an interview with Raseef22, “The burning has been going on regularly for many years since then, and it is clear that there are other types of cancer, and the health complaints I hear from doctors and parents have been related to respiratory problems, such as kidney dysfunction, spontaneous abortions, congenital disabilities, and cancer (especially lung, colon, and blood cancers), whose high prevalence is a source of great concern in these villages.”

“This is not surprising,” he adds, “having measured the pollutants released by burning organic (carbon-based) materials especially out in the open, where burning is uncontrolled and incomplete and can release harmful compounds, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which can cause cancer.” He continues, “It gets worse when there are plastics in the burning material, which tend to form compounds similar to dioxins, which are highly toxic chemicals that do not easily break down and attach to the tissues of living organisms.”

He explains that "the open burning of electronic waste (e-waste) is even more dangerous when flame retardants are used in the manufacture of plastics to prevent them from igniting, such as bromide-based inhibitors of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), a substance very similar to highly toxic substances — and is now illegal — and is released and converted to similar toxins when burned.”

He points out that things get worse when electronics contain toxic metals such as lead, arsenic, copper or zinc, the latter two of which “react with organic compounds during combustion in a way that increases the production of organic toxins,” and that “incomplete combustion produces a toxic, variable mixture of substances that results in both acute and chronic health effects, including carcinogens.”

In addition to the negative impact on health, Davis warns that "burning old air conditioners and refrigerators releases freon, a gas that contains chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) that have been proven to harm the ozone layer."

To get an idea of the extent of the phenomenon in Idna in the past, the Applied Research Institute - Jerusalem (ARIJ) conducted surveys between 2012 and 2014, which showed that the town receives between 200 and 500 tons of e-waste on a daily basis, and there are hundreds of sites designated for the recycling and burning of this waste.

Hind al-Tamezi has indirectly contributed to sustainable projects, such as the construction of an emergency center that provides treatment for defects and deformities resulting from the burning, and an education institution to protect the future of the children of Idna.

A night watch and attempts at solutions

The health of the residents of these Palestinian towns is endangered, with everyone feeling that their areas have become infested, and that the municipalities need to stop the burning in response to the continuing complaints.

The mayors of Idna and Beit Awwa have thus put in place mechanisms to eradicate the phenomenon of 'taqsh', with great success in the second half of 2022 that saw them transform their towns into areas nearly completely devoid of scrap burning. The current mayor of Idna Jaber al-Tamezi says, “The fires have disappeared remarkably in recent months. We were suffering on a nightly and daily basis from the burning of scrap and copper cables.”

The former mayor of Beit Awwa, Abdallah Suwaiti, also decided in 2018 to end the phenomenon of scrap burning during his tenure. Among the mechanisms used was the cooperation of the Idna Municipal Council with local volunteers to form a night watch to monitor and stop scrap burning taking place at night, in cooperation with the Environmental agencies and the Environmental Quality Authority.

Suwaiti for his part, also formed an awareness committee in Beit Awwa made up of preacher sheikhs, teachers, and sports club members. He says, “Everyone worked hard to fight the 'taqsh' burning, and we chased the 'taqashin' ('taqsh' practitioners) and sent their names to the Public Prosecution Office, which put some of them in prison. We forced them to sign a pledge of 50,000 shekels ($15,035 US dollars) as a deterrent to e-waste burning.”

The heads of various municipalities have also developed a mechanism to fine those involved in scrap burning and confiscate their goods. The night watch tents are still up, particularly distributed atop Idna's hills.

These municipalities are still trying, with their limited resources, to combat scrap burning. This comes after the Palestinian Authority refused $3 million US dollars of direct funding from the Swedish embassy to work on the issue in 2018. The year ended with the dismissal of Suwaiti, who had once dreamed of changing the bitter reality in his town and improving it.

In Tunisia, plastic waste is just as dangerous as the sorting and burning of e-waste. The municipalities transport it through private cars or companies to transfer centers, then to dumps managed by the Tunisian National Agency for Waste Management.

Walim Merdasi, an environmental expert in waste management and advisor to the former Minister of Environment, suggests that, “Tunisia establishes waste treatment centers in order to integrate the 'barbechas' and ensure their health, especially since transporting, storing, and burying waste poses a great danger to them.”

Since the 1990s Tunisia has moved towards waste valuation programs such as Eco'Lav — a public system for the recovery of used wrapping bags and cans made entirely or partially of plastic or metal — providing new economic opportunities for vulnerable groups that depend on the collection of waste from the streets. However, according to Inas al-Abyad, Coordinator of the Environmental and Climate function department at the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), the nation “lacks a comprehensive, long-term vision, and vulnerable groups pay the tax for this pollution, since we are talking about cases of sterility and cancers that affect some women in the town of Agareb because it contains a waste dump”. The FTDES is an independent non-governmental organization established in 2011 that seeks to defend economic and social rights at the national level.

Also weighing in on this is "EARTH'na collectif", a Tunisian youth group supported by associations active in the fields of environment and human rights, that organizes awareness campaigns related to climate change, protecting biodiversity, and monitoring violations threatening the environment and heritage. Figures by the group revealed last July that Tunisia has Africa’s third worst level of environmental pollution, at a rate of 75.12%, according to estimates by the Heinrich Böll Foundation – North Africa Office. According to the report, Tunisia fell 25 places in the world rankings to occupy the 96th spot in 2022.

This places Tunisia in front of the challenge of reducing greenhouse gas and carbon dioxide emissions by 45% by 2030, a goal it has committed to when it signed the Paris climate agreement in 2015.

These indicators give a picture of the devastating future environmental impact of plastic waste in Tunisia, as well as the daily burning of electronic waste in Palestinian towns.

In the face of all these dangers, women are trying with their initiatives to make their voices heard by the official authorities in Tunisia and Palestine, and to urge them to find solutions to these environmental crises.

In this context, the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES) presented, according to al-Abyad, “a project to structure the work of 'barbechas' in a participatory manner with several ministries, including the Ministry of Social Affairs, the Ministry of Women and Children and the Ministry of Economy”, stressing “the importance of protecting this group from accidents it's exposed to on a daily basis”.

Al-Abyad adds, “The corruption of the Tunisian National Agency for Waste Management [a non-administrative public institution that enjoys financial independence, established in 2005 and subject to the supervision of the Ministry of Agriculture and Environment] plays a role in deepening the waste crisis and transforming it into a non-temporary structure. The agency is a black box, and we do not even know its policies, like what had happened in the Italian waste crisis, which caused a major scandal in 2020.”

The Italian waste crisis refers to the 2020 seizure of 282 containers of toxic plastic waste in the port of Sousse. The waste, coming from Italy, did not meet international standards for the import and export of waste. As a result, a large number of officials were dismissed, including the former Minister of Environment, Mustapha Aroui.

In Palestine, the Israeli occupation and the policies of the Palestinian Authority play a role in Palestine’s fumbling when it comes to managing its internal resources and systematically treating its waste, which means more injustice for women who work or live in polluted areas, and the continuation of dire health and social effects in the future.

*This investigation was carried out with the support of the German CANDID Foundation.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!