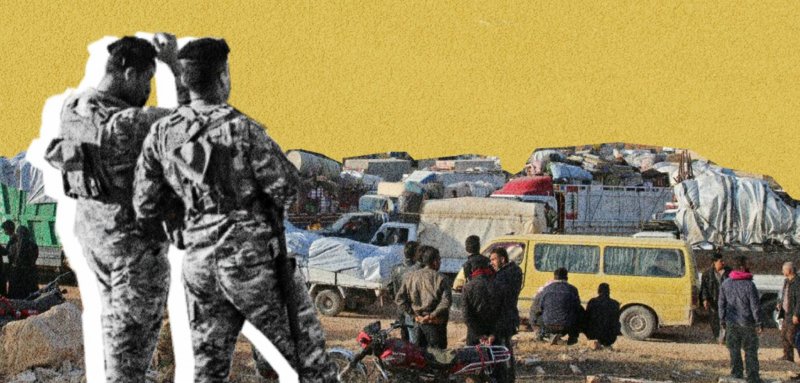

The recent campaign launched by the Lebanese authorities against Syrian refugees was not unexpected, but it was largely violent, direct, rapid, chaotic, and arbitrary at times.

The issue of returning to Syria is not new; it has been previously raised and discussed, and attempts have been made to experiment with different methods of implementing what is called "safe, voluntary return". However, the recent systematic campaign threw out all the "voluntary return" agreements that various Lebanese government entities, authorities, and influential parties had been working on for several years. This made immediate forced deportation the quickest solution due to Lebanon's inability to absorb the repercussions of Syrian refugee presence on its territory, which has entered its thirteenth year. Additionally, the Syrian regime's entry into the realm of re-establishing relations with Arab countries and its official recognition has become a reality. The presence of refugees has become a humanitarian problem that is no longer subject to a political game between the two neighboring parties, whose relationship has always been problematic.

The campaign was preceded by a clear and systematic process of inciting public opinion against the refugees, whether through statements by some authority figures or local media outlets. Since the beginning of the year, these outlets have focused their reports on the deterioration of the security and economic situation due to the presence of refugees, disseminating false information about their living conditions, such as their population count, birth rate, or the delivery of aid and assistance to them in US dollars.

There have been multiple campaigns aimed at the arrest and deportation of refugees in various forms. On April 10, a residential gathering inhabited by Syrian refugees was raided in the al-sakhra complex in the Jounieh district of Keserwan. Approximately 29 refugees were arrested according to the documentation of organizations, including the Access Center for Human Rights (ACHR), which monitors forced deportation operations and seeks to gain information and data on what is happening. The refugees were detained and taken to the Sarba barracks and then transported to the Masnaa Border Crossing, where they were deported and left in Syrian territories.

The campaign was preceded by a clear and systematic process of inciting public opinion against the refugees, whether through statements by some authority figures or local media outlets.

The fate of 11 refugees among those deported remains unknown to this day. Zahra (pseudonym), 29, the wife of one of those who were deported, says, "My husband entered the country legally before 2019, so the decision (Supreme Defense Council decision to deport those who entered after 2019) does not apply to him. He had a residency permit, but he couldn't renew it due to difficulties in obtaining a new one. We are registered with the UNHCR, but he was taken away by force in front of the children. Even my little daughter was so terrified she involuntarily wet her clothes."

Until today, Zahra knows nothing about her husband. She hears scattered news every day, but there is nothing certain. She just wants to know if he is in Syria or Lebanon.

Cross-border trafficking

Umm Ibrahim, a widowed woman in her forties living in the Qubbah area of Tripoli with her three children, recalls the abduction of her eldest son and the subsequent extortion she was subjected to by human smugglers to reach him. He was arrested while going to buy bread at the Qubbah checkpoint on May 2. He was directly deported through the Shahdara border crossing in the Wadi Khaled border area, known for its human smuggling activities and being under the control of smugglers and the Fourth Division of the Syrian army.

After the kidnapping, Umm Ibrahim was contacted by one of the human smugglers who claimed to be trying to help her. He said that her son had reached the Fourth Division along with five other refugees, and that she had to provide $200 per person so that her son would be returned to her.

According to the smuggler's audio recordings, he deals with the Fourth Division regarding deported refugees. Several witnesses and victims have also mentioned instances of blackmail and extortion on the Syrian border.

After several negotiations, the mother paid $200 in exchange for access to her son. However, the Lebanese Army intercepted the smuggling operation and re-arrested him, handing him over to the Fourth Division, which took him to the Military Security Branch in Homs, according to the mother's account.

After her son was kidnapped, Umm Ibrahim was contacted by a human smuggler claiming to help her. He said her son had reached the Fourth Division along with 5 other refugees, and that she had to provide $200 per person so that her son would be returned to her

"M. A", 35, a Syrian refugee who was forcibly deported despite legally entering Lebanon and possessing an asylum card, talks about the extortion and trafficking ordeal he and one of his relatives faced at the border. He was deported after a raid on the village of Al-Mazraa in the Kfardebian area of Keserwan district on April 11, along with 35 other refugees from the same area. They were left on the Syrian border after being handed over to members of the Fourth Division, who in turn placed them with some human smugglers at the border, and thus began the brokering operations that lasted for a full day.

The victim says that those who were able to pay sums of money ranging from $150 to $200 US dollars, by contacting their families to secure the amount, were returned illegally to Lebanon. It is worth noting that the exchange and delivery process took place within Lebanese territories and takes place in various regions inside Lebanon. There are a large number of refugees waiting on the border, with their fate hanging between the hands of human traffickers and the Fourth Division.

"M. A" tells Raseef22, "I don't want to spend my life in Lebanon. We know how bad Lebanon's economic situation is today. But after 12 years of asylum, I cannot return to Syria. I am wanted by the army because I failed to fulfill compulsory military service, and I belong to an area outside the control of the regime. I fear for my life and the lives of my family. None of us lead a comfortable life in Lebanon, but if the choice is between living in the most minimal conditions and death, I choose the former."

It is worth mentioning that in its report issued on May 19, the ACHR Center documented cases of deportees being handed over to smugglers. The report stated that "75 refugees among the deportees told the center that the Syrian authorities handed them over to human smugglers present on the Lebanese border, and negotiations were conducted with them to return to Lebanon in exchange for sums of money ranging from $150 to $300 per person, while the amounts reached approximately $3,000 for individuals facing direct security risks in Syria. Moreover, 51 refugees confirmed that they were directly handed over to the Syrian authorities by the Lebanese Army."

The smugglers and their greed

"A. S", a 27-year-old Syrian refugee working as a day laborer with an "electrician" in Lebanon and residing in Jounieh, was arrested while leaving work on April 23. He was taken to the Sarba station and then handed over to the Fourth Division, which, in turn, handed him over to the smugglers. He says, "I was taken with a group of about 45 people to a border village, where we were distributed among several houses that appeared to belong to the smugglers. Most of them are residents of border villages. We were offered meals in exchange for sums of money and were allowed to make phone calls to reassure our families, also in exchange for money."

The victim says that for those who were able to pay sums of money ranging from $150 to $200 US dollars, the smugglers would easily secure their illegal return to Lebanon through the cover of the Fourth Division

The victim mentions that the smugglers took around $7 for each meal and $2 for a phone call. After a short period, negotiations began while he was staying in one of the smuggler's houses, and he paid $200 in exchange for his return to Lebanon.

The extortion practiced by the smugglers relies on communicating with the families (mothers and wives, in particular). It is common for young men to be deported, and during the communication process, agreements are reached. Umm Ibrahim was subjected to significant psychological pressure during her communication with the smuggler to recover her son, which ultimately failed. Umm Ibrahim and other women are awaiting news about their deported sons and husbands. They never expected their fates to be left in the hands of human smugglers who openly engage in extortion and in trafficking them. The smugglers justify their actions by claiming that the amounts they receive are bribes for both the Syrian and Lebanese sides, and the smugglers' share does not exceed 20% of the total amount.

Human smugglers – or smugglers in general – have been present between the Syrian and Lebanese borders since before the Syrian revolution. Most of them come from border villages where families of both Syrian and Lebanese nationalities coexist. In the mentioned cases in the report, the smugglers communicate with the families and relatives of their "detainees" in order to obtain amounts of money for their return to Lebanon.

Hussein, 31, a smuggler who works in drug smuggling and sometimes human trafficking, claims, "Sometimes I provide a service to those in need by smuggling them, but I don't prefer this type of work." He talks about how smuggling has increased and changed after the Syrian refugee crisis, and he says, "New influential individuals have entered the business, and that's why I don't work in human trafficking a lot. It is an operation that has its own people and is fraught with risks. After the war in Syria and the spread of supported factions, the operation primarily adheres to influential individuals, and I don't want any problems with anyone."

Human smugglers have been present between the Syrian and Lebanese borders since before the Syrian revolution.

The journey beyond borders

After the fierce battles in the countryside of Qalamoun and Al-Qusayr and the Lebanese Hezbollah's control over the region in 2013, the Ba'ath Brigades forces spread and extended their influence to the villages whose residents were displaced. These brigades recruited their members from pro-Syrian regime villages in the Qalamoun. According to some people and smugglers, including Hussein, no one wants to mess with them. They are stationed in the border village of Rablah in Syria and receive huge sums of money for smuggling operations, and they have multiple routes.

The price in this trade varies depending on the method. There is smuggling done by car "from house to house", which is the most expensive method, ranging from $400 to $600 US dollars. It requires strong and direct connections with an influential smuggler, often carried out by one of the close associates of the top smugglers. There are other methods done through various crossings, including transportation, where the person may have to spend a night or several nights in a border village at the smuggler's house, for the most part. Then they continue their journey either by motorcycle and on foot for several kilometers, and then by microbus after reaching Lebanese territory, or by a car that transports them collectively.

Cars are changed at least once or twice, and the prices of this type of smuggling range from $200 to $400. Nothing is guaranteed, as it is possible for a person to pay $400 in the hope of reaching Lebanon by car, but then they're surprised to find themselves needing to spend a day in a house with a large number of people, then having to walk for hours, and riding a motorcycle. This is what happened to "M. R.", a 44-year-old Syrian refugee who had evaded military service in Syria. He decided to come to Lebanon with his family consisting of his wife and daughter to later travel to a third country.

After paying an amount of money to the smuggler and receiving promises that they would reach Lebanon by car, he was shocked to find that he and his family had to sleep with about twenty people in a makeshift shelter that seemed to have been a pen for animals. They had to walk a long distance and then ride motorcycles. He refused and returned to Syria. However, the smuggler did not refund the full amount, only deducting half of it, claiming them as fees and that he had missed a real smuggling opportunity.

Voluntary return and deportation

This phrase has been echoed in numerous official statements in Lebanon since the beginning of 2019, summarizing the position of the Lebanese state regarding the presence of refugees on its soil. These refugees fled from the grip of violence only to experience violence in various forms in the country of their asylum, and their fate became subject to a network of decisions, settlements, and reconciliations taking place within Syria and Lebanon and between the two countries.

The issue of "voluntary return" is a process of cooperation between the Syrian and Lebanese parties, implemented through various methods involving multiple actors. The Syrian side offers settlements for the status 0f Syrian refugees from specific areas and provides facilitations for their return to those areas, most of which are merely formal. Since the beginning of the return process, cases of arbitrary arrests and enforced disappearances of returnees in Syria have been recorded and documented by various entities, including Amnesty International, in its 2021 report titled "You're Going to Your Death". On the Lebanese side, several actors are involved in this process, and sometimes political parties and small groups intervene in the mechanisms of return operations in Lebanon, where Syrian refugees are used as fuel for conflicts between multiple Lebanese parties.

Refugees are living in deteriorating conditions, especially after the crisis and economic collapse in Lebanon. The violence against them has been increasing day by day. Since the beginning of the 'voluntary return' issue and before the campaign we are witnessing today, a policy of intimidation has been imposed against the refugees based on their economic, social, and legal status, as some are forced to register their names on settlement lists out of fear of deportation. Additionally, there are economic pressures and strict measures regarding Syrian employment, sometimes leading to the arrest of some individuals, closure of shops, and the issuance of laws that specify the number of Syrian workers compared to Lebanese workers.

"At times I provide a service to those in need by smuggling them. After the war in Syria, new influential people entered the business, and that's why I don't work in human trafficking a lot. It's an operation that has its own people and is fraught with risks"

As for legal residency, it is an ongoing problem in Lebanon. Some residency permits are impossible to obtain. The Supreme Defense Council issued a decision to deport Syrians who entered Lebanon illegally after April 24, 2019, and this decision has been implemented several times. It is the pretext currently used by the Lebanese government to justify the deportations being done, although according to monitoring and statistics from several institutions and interviews with witnesses, it has been confirmed that not all individuals subject to this decision meet its criteria. The cycle of violence they face does not end there; it continues to escalate to the extent of affecting school students. In 2021, the Ministry of Education banned Syrian students from taking exams for the preparatory and secondary certificates unless they possess legitimate residence permits.

Official statements discussing deportation and the ongoing campaign led by the army have been numerous. On May 2nd, the Ministry of Interior issued a decision requesting regional governors to instruct municipalities and mukhtars to launch a national survey campaign to enumerate and register refugees in order to regulate their work and determine their legal status. Despite human rights recommendations, the General Security Directorate of Lebanon announced that it resumed the voluntary return plan on May 4th, by settling the status of refugees who wish to return at the border centers.

On May 23rd, during a dialogue meeting at the Italian Society for International Organizations (SIOI) in Rome, the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates, Abdallah Bou Habib, stated that "the Syrians in Lebanon do not qualify as political refugees, as most of them are in Lebanon for economic reasons." He also mentioned that "there are two million Syrians in Lebanon, and this number threatens the composition of the Lebanese structure, as there has always been a balance between Christians and Muslims who feel equal without superiority of one over the other."

Despite these statements and others, the fate of the refugees remains at risk. In a widely circulated video on May 23rd, the father of the defected Syrian officer, Major S. N. S., who resides in Arsal, pleaded with international organizations to prevent the deportation of his son to Syria. His son had been arrested at the beginning of the month during his visit to the General Security center in the town of Labweh in the Bekaa region to settle his residence status.

Mustafa (pseudonym), 38, a defected army officer since 2015, expresses his fears of deportation and says, "The campaign does not discriminate against anyone. If they want to target those who can actually return to Syria, they should conduct a comprehensive census and survey. There are many like me. We cannot even think about returning. I am wanted and currently spend my time moving around, fearing to settle in one place in anticipation of any raids. I cannot obtain a passport to settle my status because I defected, and I do not have any identification papers. There is no institution supporting me to obtain my documents. I try to contact the Commission daily to demand the right to resettlement for myself and my family, but so far, it has been in vain. We are all living in danger."

As for Umm Ibrahim, she is still waiting for a solution that would allow her son to return to her. It seems that a solution has been delayed. She entered Lebanon with the hope of resettlement and had registered with the Commission, waiting for her and her children's cases to be studied in order to continue their lives in another country after she lost her husband in the war, and she and her children survived. She says, "I don't know what to do now. I have lost my eldest son. On the day of his arrest, I called the United Nations, and they told me that despite being registered as refugees, they are unable to do anything and will establish a specialized committee to contact me. To this day, this committee has not contacted me."

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!