"Why do you deal with polygamy with such sensitivity when it is women's nature to accept it?" A sheikh once asked me. I was unsure how to answer this question, which seemed to have an obvious answer. Should I explain to him what polygamy means for women, or should I talk to him about the name of God, Al-'Adl (The Just)? I chose to remain silent because any explanation would be futile as long as men remained the opponent and the judge.

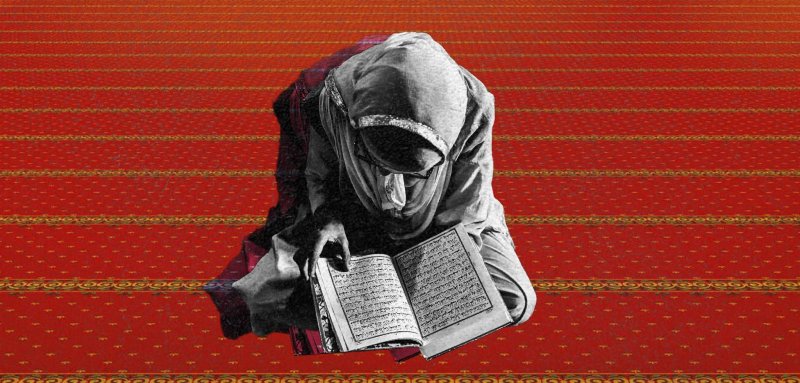

What if we took off the glasses, replaced the lenses, and read the Quran through women's lens? And what if we read the Quran as one unit, not as separate verses? How much would our understanding of the ethical system in the Quran differ then, especially since it has been overshadowed by millions of specific rulings and surface rituals?

This ijihad (legal reasoning) has already been done, and has been elaborated in detail by Nour Rafi'a, an Indonesian researcher and lecturer on Quranic interpretation methodologies at the Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University and the Institute of Quranic Studies in the Indonesian capital, Jakarta. She presents a whole chapter titled "Reading the Quran through Women's Experiences" as part of a recently published book by Dar al-Kutub Khan, titled "Justice and Ihsan in Marriage: Towards Ethical Values and Equitable Laws," edited by Ziba Mir-Hosseini, Malki al-Sharmani, Jana Raminger, and Sarah Marso. It is one of the outcomes of a research project conducted by the Musawah (Equality) Movement for several years, titled "Restoring the values of Justice and Ihsan in Marriage."

What if we replaced the lenses, and read the Quran through the lens of women? How much would our understanding of the ethical system in the Quran differ then, especially since it's been overshadowed by millions of specific rulings and surface rituals?

Rafi'a believes that reading the Quran through women's physical and social experiences is essential to achieving true justice. She provides examples from the verses that address breastfeeding and the responsibilities of parents, highlighting women's experiences and the pain and suffering they entail. Through these verses, the Quran aims to change the reader's perception of motherhood from a demeaning matter or a pretext for discrimination to a perspective that celebrates determination and perseverance.

Rafi'a explains to Raseef22 that this new perspective allows us to see that both spouses (not just the husband) are the true purpose of marriage and the criterion for its success, and that rights are mutual, with each spouse taking care of the other.

She adds, "If we apply this approach to family laws, for example, we would treat intimacy as a right for both parties, not just a right for the husband and an obligation or duty for the wife. This right should be exercised in a way that ensures peace and tranquility for both of them."

How revelation gave justice to women in three steps

Rafi'a emphasizes that one of the most important purposes of the Islamic revelation that took place over the course of 23 years was to rectify the status of women and girls. The Quran consistently reaffirms the full dignity and complete humanity of women. Like any path seeking social change, the Quranic approach had a starting point, an intermediate stage, and an end goal. Hence, we can identify three types of verses related to women's issues.

Researcher Rafi'a emphasizes that one of the most important purposes of the Islamic revelation that took place over the course of 23 years was to rectify the status of women and girls. The Quran consistently reaffirms the full dignity and humanity of women

The first type represents the starting point, which includes verses that depict a society where women are considered inferior and address those who live within this context, such as verse 2:223 of Surah Al-Baqarah: "{Your women are a tilth for you (to cultivate) so go to your tilth as ye will (approach them ˹consensually˺ as you please), and send (good deeds) before you for your souls}".

As for the second type, it reflects the intermediate stage, where we move a step forward, calling for social justice within a system governed by patriarchy and limited by political, economic, and social constraints. An example is verse 4:3 of Surah An-Nisa': "{If you fear that you might not treat the orphans justly, then marry the women that seem good to you: two, or three, or four. If you fear that you will not be able to treat them justly, then marry (only) one, or marry from among those whom your right hands possess. This will make it more likely that you will avoid injustice}".

Finally, the third type represents the ultimate goal of the Quranic path, establishing a model that ensures true justice for all humans, including women. Examples of such verses include verse 9:71 of Surah At-Tawbah: "{The believers, both men and women, are allies of one another. They enjoin good and forbid evil (command decency and forbid wickedness)..}"

The scholar believes reading the Quran through women's physical and social experiences is essential to achieving true justice, ie. the Quran aims to change the reader's perception of motherhood from a discriminatory matter to one that celebrates perseverance

A sales contract or a strong covenant?

On a daily basis we encounter religious and societal discourse about marriage, often filled with shouting, wailing, and severe threats. It is a recurring and monotonous discussion about marriage like it's a sales contract. And we continue to ask, generation after generation, how did we deviate from the Quran's moral message and arrive at such a highly demeaning formula for both parties and a relationship described by the Quran as a strong covenant?

This is the question that the three authors, Omaima Abou-Bakr, professor of English and comparative literature at Cairo University and a founding member of "The Women and Memory Forum" and a member of the "Knowledge Building Team" affiliated with the "Musawah" movement, Asmaa Lamrabet, a researcher in women's issues in Islam and former director of the Center for Women's Studies in Islam at the "Rabita Mohammadia des Oulémas (Mohammadía League of Scholars)" in Morocco, and Mulki Al-Sharmani, associate professor of Islamic Studies and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Helsinki in Finland, attempt to answer through another chapter of the same book.

Researcher Rafi'a emphasizes that one of the most important purposes of the Islamic revelation that took place over the course of 23 years was to rectify the status of women and girls. The Quran consistently reaffirms the full dignity and humanity of women

The three researchers present a critique of the interpretive methodologies that have not delved into the ethical system of the Quran, failing to connect the legislative aspects in the jurisprudential rulings with the moral and ethical obligations. They then discuss some interpretations that adopt a partial approach, moving from one verse to another without tracing the links in the meanings and purposes of the Quranic verses across different surahs (except for those linguistic or purely jurisprudential connections).

The authors propose a comprehensive interpretive methodology that studies the Quran from an ethical, linguistic, and historical perspective, linking the various relevant verses. Through this methodology, the Quran lays the foundations for human relationships based on several fundamental principles, the first of which is that human beings are equal in their human worth because they are created from the same source and are responsible for embodying piety and righteousness. The second principle is that the Quran defines marriage as a strong covenant between equal entities, in a special and strong bond of trust, commitment to the best interest of the other party, and mutual care. This bond holds the same importance that distinguishes the the bond between the prophets and the Creator. Thirdly, the Quran establishes three main pillars to maintain and preserve this bond: tranquility, affection, and mercy.

Here, Omaima Abou-Bakr believes that when both spouses live by the conviction that there is no superiority, priority, or unequal power relationship between husbands and wives, especially in the sense of imposed religious authority in managing affairs, this is reflected in healthy and equitable relationships within the family, characterized by mutual respect and understanding based on human equality, moral conduct and noble character, rather than who is stronger or who leads and who decides.

When I was young I wished I'd find a female religious scholar, even just once—a woman who can truly understand me, instead of the hundreds of men who constantly judge me based on their perception of what a woman's nature, clothing, and even emotions should be

Ethics and the law.. Is there a way to reconcile them?

The Quran calls for the establishment of marriage on foundations that go beyond natural emotional love, as that would not be enough for spouses in a marriage. It emphasizes the importance of them being committed to making this relationship flourish through compassion and empathy towards one another, especially in times of discord and crises. This leads us to focus on the concept of "Ihsan" (excellence – to do what is good and beautiful toward others) in the Quran, as explained by Amira Abou-Taleb, a fellow researcher in the doctoral program at the Faculty of Theology at the University of Helsinki, where her thesis is about the concept of "Ihsan" in the Quran's view of the world.

When reading the verses that address the concept of "Husn" (beauty and excellence) in a comprehensive manner, we can understand the complete cycle of the concept of "Ihsan", in the sense that "Husn" is encompassed in all creation, and "Ihsan" is required of humans in return. The word "Ihsan" is derived from the trilateral root "H-S-N", which combines the meanings of goodness and beauty, and appears 194 times in the Quran. This is evident in verse 90 of Surah An-Nahl, which emphasizes justice and excellence in a strong and decisive tone: "{Indeed, Allah commands justice, grace, as well as courtesy to close relatives. He forbids indecency, wickedness, and aggression. He instructs you so perhaps you will be mindful}".

Several sheikhs and scholars confirmed that it's not enough for sheikhs alone to practice ijtihad in family laws and women's rights. There must be a committee of men and women who specialize in religion and possess the necessary knowledge of women's realities

Abou-Taleb affirms to Raseef22 that "we have become accustomed to simplifying matters and imposing prevailing concepts on various situations and contexts, linking them to religion without considering the impact of these concepts on what the Quran asks of us. Ihsan, on the other hand, is an absolute and variable concept that makes us reflect on the meanings of goodness and beauty in every situation and avoid harming any party."

Undoubtedly, after all these moral messages, it becomes difficult for us to comprehend the vast gap between the values of Ihsan in the Quran and the ugliness of the living reality for Muslim families. This makes amending laws, in a way that ensures justice, a crucial step towards reclaiming the values of Ihsan.

While these early interpretive works are an important part of the interpretive heritage, we draw inspiration from them in terms of the interpreters' keenness to contemplate and reflect on the verses of God. However, the combination of reason and conscience is no longer a luxury, but a timely obligation. Understanding the moral message of the Quran and using it to derive more just judgments, rather than recycling old patriarchal interpretations, has become necessary.

When I was young I kept wishing to find a female 'sheikha' (religious scholar) or mufti (Islamic jurist), even if only once – a woman who can truly understand me, instead of the hundreds of men who constantly judge me based on their perception of what a woman's nature, clothing, and even emotions should be.

"I later realized that ijtihad (legal reasoning) and exerting effort in religious knowledge does not solely require male scholars but also those who possess the tools of research and analysis, and those who convey the lived – and living – reality to us"

Later, I realized that ijtihad (legal reasoning) and exerting effort in religious knowledge does not solely require male scholars but also those who possess the tools of research and analysis, and those who convey the lived – and living – reality to us.

When preparing my master's thesis, I spoke with four clerics, including sheikhs, religious scholars and academics, three of whom confirmed that if we want to make diligence and practice ijtihad in family laws and women's rights, it is not enough for sheikhs to practice ijtihad alone. There must be a committee consisting of men and women who specialize in religion, and also possess the necessary knowledge of the reality of women. I imagine that this is a vital foundation and that this is what confirms that change is inevitably coming.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!