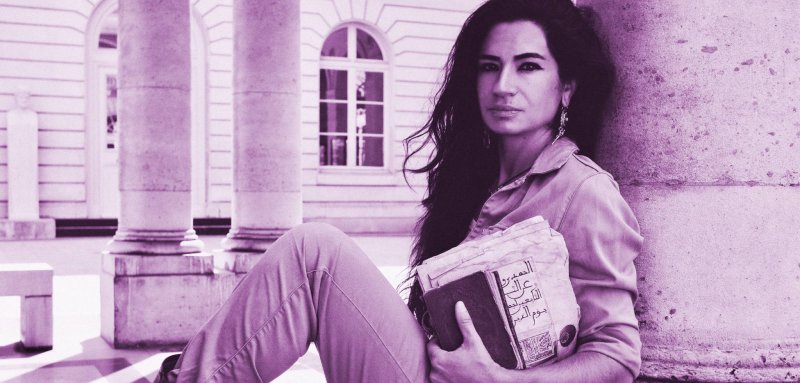

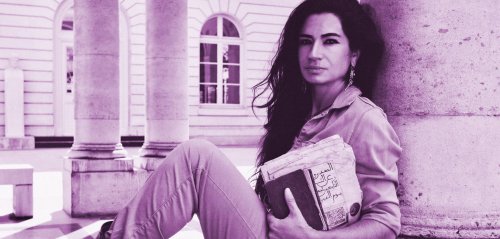

Dr. Eléonore Cellard is a specialist in Qur’ānic manuscripts. Before she started her research activities in 2008, under the supervision of François Déroche, she first studied Arabic Language and Literature. In 2015, she submitted her dissertation entitled “The written transmission of the Qur’ān. Study of a corpus of manuscripts from the 2nd H./8th CE”. Until 2018, she carried on her research at the Collège de France, as research assistant and post-doctoral researcher. Involved first in the French-German Coranica project, then in the Paleocoran project, she published Codex Amrensis 1, the first volume of the collection of facsimile and diplomatic editions of the earliest Qur’ans (Brill, 2018).

Her work incorporates fascinating Islamic scholarly traditions like traveling in search of knowledge "rihla fi talab al-‘ilm," and the spiritual power felt through working with relics and decoding what they symbolize.

In this article, Cellard shares with Raseef22 readers how her story with Qur’anic studies began, and offers an insight into the world of Qur'anic manuscripts.

How the Fascination with Kufic Script Led to Paleography and Codicology

Cellard studied first Arabic Language and Literature, before turning to Arabic paleography and codicology. About this background, she says, that even before studying Arabic at the university, she was already fascinated by Qur’anic manuscripts: "The startling aesthetic of the Kufic script on sheets of parchment. I spent hours collecting images to make reproductions, trying to give my paper the appearance of parchment and imitating every detail of the tracing of the letters. At the time, I had no idea that I was making observations that are part of scientific fields called, in academic jargon, paleography and codicology".

The startling aesthetic of the Kufic script on sheets of parchment led Eleonore Cellard, a specialist in Qur’anic manuscripts, to a trip of unfolding the mysteries of these ancient manuscripts

She continued these reproductions at “Langues’O” university in Paris, where she decided to study Arabic language and script: "Because the Qur’ān, as well as other literary monuments such as archaic poetry, are the origin of classical Arabic. Arabic language and literature are thus connected to the text of the Qur’ān, to its meaning and history. During eight years of university education, I had my first field experiences in Arabic countries (Syria, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco) in which the Qur’ān plays an important role".

It was only later that Cellard discovered the history of the Qur’ān and its manuscripts through two disciplines--paleography and codicology—that are considered “auxiliary to history", as she says, "I studied them with François Déroche, a great specialist of Qur’anic manuscripts. Paleography and codicology are essential methods for reconstructing the chronology of manuscripts that do not contain a written date, which is unfortunately the case in the early period of the Qur’ān".

As of today, there is no evidence of dated manuscripts from the first two centuries of Islam, says Cellard, "But paleography and codicology also open other perspectives for us by providing direct access to the world of the craftsmen, scribes, and readers of the Qur’ān. We are nevertheless forced to admit that our present-date knowledge of the early transmission of the Qur’ān, including scribes and scribal practices, the production and copying of manuscripts, and their circulation and transmission, is relatively superficial and merits far more extensive investigation".

Ancient Eastern Languages

While, regrettably, very few young Arabs are showing interest in the study of ancient eastern languages, Cellard has studied Arabic, Syriac and Akkadian languages, urged from the fact that "The Qur’ān is presently believed to be the first evidence of a written Arabic-language literary tradition, as well as the first book", she declares, "We therefore have to ask what pre-existing conditions made this act of writing possible. Was there parchment being produced and traded in Arabia? What writing practices circulated in the region? How were books assembled in that period?"

This is how she became interested in the writing practices of other Eastern cultures "to understand ways in which the Qur’ān is connected to the cultures that preceded it, and how this cultural and material heritage was transmitted to the craftsmen of the Qur’anic Book. Akkadian is among the most ancient Semitic languages, and we have access to an extraordinary documentary corpus in cuneiform script. With Egypt, it is one of the cradles of scribal practices. For Syriac, we are already in a time and a world that is closer to that of the Qur’ān, and the interactions between material cultures are clearer".

Eastern cultures and languages, like Akkadian and Syriac reveal ways in which the Qur’ān is connected to the cultures that preceded it, and how this cultural and material heritage was transmitted to the craftsmen of the Qur’ānic Book

Cellard believes that the earliest scribes of the Qur’ān benefited from this cultural and material heritage to produce their manuscripts: "Although they are fragmentary, the most ancient Qur’anic books that remain available certainly date from several decades after the Qur’ān was canonized. But even at the time, they exhibit advanced techniques of manufacturing books and scribal practices that could not have suddenly developed from one day to the next or without contact with other cultures".

What was the extent of interaction between these cultures? Were there privileged interlocutors, or did craftsmen directly intervene in the manufacture of Qur’anic manuscripts? "There is currently no material evidence of these processes", she says, "there was a period when it was thought that the horizontal format of copies of the Qur’ān reflected the necessity of distinguishing the Qur’ān from other books that were formatted vertically, particularly Christian books".

Cellard's research has shown that in reality, the invention of the horizontal format was first related to economic constraints: "In my view, the craftsmen of the Qur’anic book did not design the physical shape of the Qur’ān in opposition to other book cultures in the region. On the contrary, based on this regional heritage, craftsmen and scribes were incredibly dynamic in searching for new graphic expressions and exploring different materials. Clearly, the necessity of copying the Qur’ān enabled calligraphy and the craft of making parchment to reach their zenith".

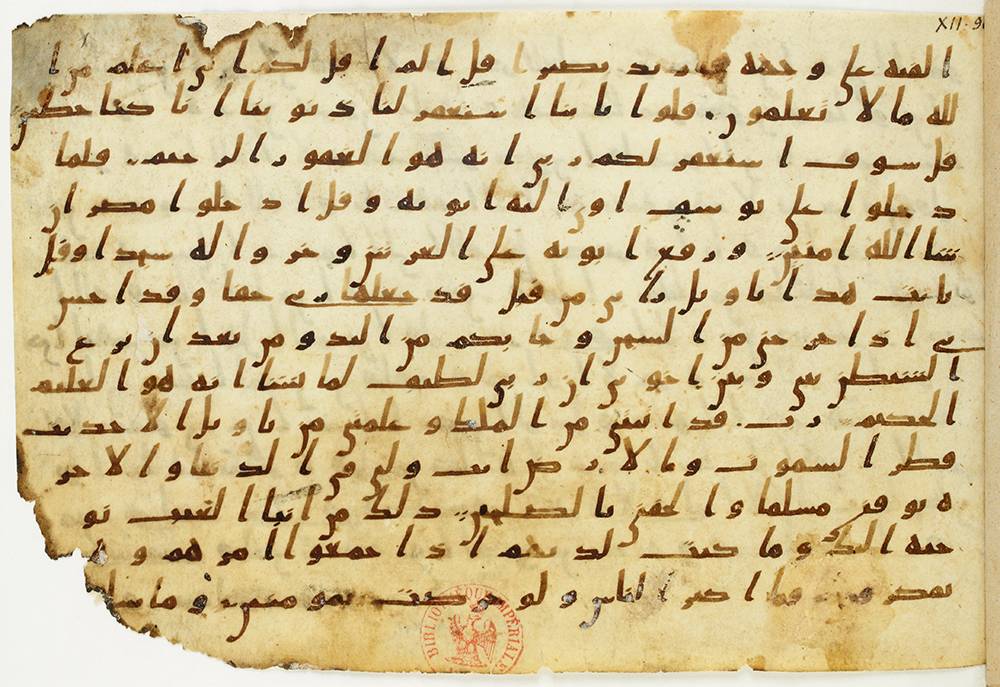

A page of the Codex Amrensis 1 (Paris, BnF Arabe 326. Source: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Codex Amrensis 1

The Codex Amrensis 1, once kept in in the ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ Mosque at Al-Fusṭāṭ, was among the examples that illustrate the existence of an ancient pattern of transmission whose characteristics closely resemble the Vulgate Qur’anic

Cellard's Codex Amrensis 1, the first volume of the series Documenta Qur’ānica, contains images and Arabic texts of four sets of fragments (seventy-five sheets) of the Qur'an codex, once kept in the ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ Mosque at Al-Fusṭāṭ, and raises the issue that this version varies from today’s reference editions of the Qur'an in verse numbering and has a different orthography: "I encountered particular variations with respect to today’s standard Qur’anic text", she denotes, "The Codex Amrensis 1 was among the examples that illustrate the existence of an ancient pattern of transmission whose characteristics closely resemble the Vulgate Qur’anic. The manuscript was probably produced in the first half of the 8th century by a professional copyist, although is small in size (which is related to its horizontal orientation) and bears evidence of an attempt to economize parchment".

Cellard mentions that only 20% of the manuscript remains, although its construction indicates that it originally constituted a complete, possibly several-volume Qur’ān: "Among its important textual features is that the order of Surats and Verses conforms precisely to the order of the standard edition of the Qur’ān. The text is also identical, with the exception of several copyists’ errors (which are common in any handwritten text). There are a number of orthographical variations, particularly linked to notations of long vowels that are indicative of an older version in the in-progress Arabic writing system. But this manuscript was clearly already part of a pattern of highly controlled written transmission of the Qur’ān".

One particularity of this volume, she denotes, "unlike the large volumes produced slightly before, and even during the same period, is the frequent use of diacritical marks. They are often used to specify the person in conjugated verbs of imperfect/present tense. I think this is direct evidence of the function of these smaller volumes as reading aids, almost certainly within the public context of the mosque. Other variations are also linked to the locations of separations between verses. In some cases, the separation is not noted, a potential omission by the scribe. But in other instances, there are more separations than in the standard edition. These novel separations often appear in places in which pauses are indicated. This suggestion that the symbol functioned to mark the verses' division merits further investigated, possibly involving other factors connected to reading practices".

Studying the Codex Amrensis 1 revealed different types of variations to Cellard. But she thinks that "it is crucial that we use these analytical methods to study all of the manuscripts that we have available, before addressing the question of the precise nature of these variations. Only this exhaustive work will enable us to have an overall view of the parameters of the fixation of the text of the Qur’ān".

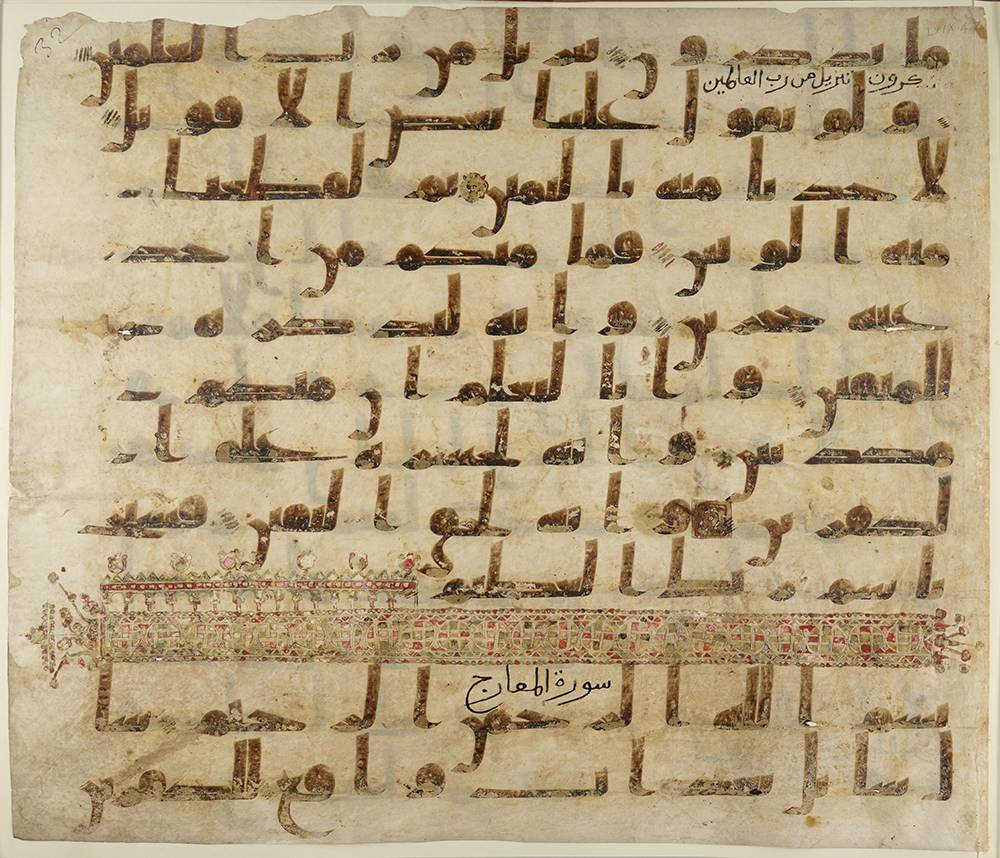

A page of the large Qur'an attributed to Uthman (Paris, BnF Arabe 324. Source: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The Transmission of the Qur’ānic Text

Cellard's research, not only helps to reach a new vision of the history of the transmission of the Qur’anic text, but also contributes to understanding Islamic history, as she puts it: "Studying manuscripts has already increased our understanding of the history of Islam. The existence of manuscripts whose age has now been proven using paleography or scientific dating techniques such as Carbon 14 has enabled the refutation of hypercritical arguments that surfaced in the 1970’s. These arguments specifically questioned the existence of a genuine Qur’anic corpus before the late 8th century CE".

The contemporary study of manuscripts to which she is attempting to contribute "reveals that the written transmission of the Qur’ān played an important role in the cultural and religious environment of early Muslims at least as early as the second half of the 7th century CE (it would be risky to venture more precise dates for the moment). There remain many unanswered questions, including more precise dates for copies, exactly where they were fabricated, and the identities of the scribes, as well as the circumstances of production and circulation of the manuscripts. I’m confident that we will shed light on some of these questions in the years to come".

Studying manuscripts has already increased our understanding of the history of Islam. The existence of manuscripts whose age has now been proven has enabled the refutation of hypercritical arguments that questioned the existence of a genuine Qur’ānic corpus before the late 8th century CE

It must be acknowledged that in the past six years, the study of manuscripts has significantly progressed, says Cellard, "Digital imaging has allowed a number of institutions that possess manuscripts to make available a growing number of images online. Special permissions are no longer needed to consult manuscripts that can now be consulted online from one’s sofa! The Internet and social networks have also facilitated access within the academic world.

This dynamism, which has been particularly remarkable in the context of ancient Qur’anic manuscripts, has, in Cellard's view, "encouraged institutions to conduct advanced studies such as Carbon 14 dating and ink analysis. Nevertheless, despite all of the benefits that we derive from these new approaches to research, it is important to remember that manuscripts are three-dimensional objects in different formats and composed of a variety of materials. Because these features are part of codicology, they are indispensable for a fuller understanding of manuscripts and their history. And unfortunately, exclusively manipulating digital images is causing this field to disappear despite the fact that it still has a great deal to say".

The Qur’ān Attributed to ‘Uthman

One of the most exciting Qur’anic manuscript Cellard examined is The Qur’ān attributed to ‘Uthman, she says: "It also comes from the ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ Mosque at Fusṭāṭ is among the most fascinating manuscripts I have encountered. The manuscript, which was probably produced sometime in the 8th century CE, was originally a colossal object weighing at least 50 kilograms. It clearly represented a considerable investment as well as a technical challenge in terms of book production (including adapting the dimensions of the script and binding), because each of its approximately 700 pages was of the maximum size that can be obtained from a single animal skin. The pages of the manuscript are currently dispersed among different collections, including fifty pages at the French National Library in Paris. In fact, it was with these pages that I began working on manuscripts 12 years ago. But the observations and hypotheses that I derived from studying them were limited.

New perspectives became available after I completed my dissertation with the Franco-German Paleocoran Project (2015-2018) in which I participated. The goal of the project was to assemble scattered fragments of manuscripts from the ‘Amr mosque and to reconstitute manuscripts to be able to study them in great detail. Despite our best efforts, however, we were not able to gain access to important collections that contain additional pages of this famous Qur’ān".

Cellard is currently engaged in a one-year individual project that is financed by the Ministry of the Interior: "Last February, I was able to gain access to a large portion of the manuscript located in the Egyptian National Library in Cairo (Dār al-Kutub al-miṣriyya), a place that remains difficult to access. There are other sites to visit before producing a truly large-scale, multi-dimensional study of this fascinating manuscript. But the project has also proven to be a human adventure. The times that I have spent in libraries have allowed me to have privileged contact with the conservators and restorers who transmit these testimonials to us and who watch over them".

One can not miss the passion that is profoundly inspiring in Cellard's work, and for her, "passion and enthusiasm are a true source of energy on my research. Research is not always easy: there is no straight, linear progression. It often happens that we invest ourselves completely in a project that yields no significant findings or results. We experience a number of difficult periods, including phases that cause us to question our professional choices..".

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!