If the Caïd — a position in the central government's administrative apparatus and the inheritor of Amghar (Tamazight for Sheikh, locally known as a tribal chief) — is a Makhzanian (Makhzen, central government) invention, then the latter, when appointed by the Makhzen, is the co-optation and appropriation of an indigenous "gerontocratic" institution (the rule of sheikhs and elderly chiefs) by the central government. Imgharen (tribal chiefs) were appointed by the Jmaas (tribal gerontocratic councils) to carry out duties at the various levels of tribal hierarchy, where power was widely distributed within its structures.

The tribal confederation of Aït Atta gives us a remarkable example of this institution. Through the dual principle of “annual rotation and complementarity” [Hart, D. 1967; Gellner, E. 1976], tribal chiefs were elected by a council that represents all the factions, at the local and village level, to elect the 'Amghar n’Tmazirt', or the local chief, as well as the 'Amghar n’ufella', the top chief, at the head of the tribal confederation, for a period of one year.

Imgharen (tribal chiefs) were appointed by the Jmaas (tribal elder councils) to carry duties at the various levels of tribal hierarchy, where power was widely distributed within its structures

The principle of rotation implies that each year an Amghar is elected from a different faction at the local level, or a different Khoms* (fifth) of the tribe at the top level. As for the principle of complementarity, it means that Ajmu’, the council of electors and advisors, is composed of representatives of all factions (or fifths), except the one that the Amghar is elected from. A tribal chief is chosen from among the candidates of the remaining faction (or fifth), and has the power to impeach and replace them in case of misconduct. Other tribal chiefs are elected by the councils, or appointed by the elected Amghar, to supervise particular duties, such as 'Amghar n’tougga' or 'Amghar n’ou Agdal', whose duty is to supervise all matters related to pastures.

Although this institution continued to survive until the early 20th century among communities that lived beyond the reach of the Makhzen’s authority — such as the Aït Atta tribal confederation — local Sheikhs within the territories ruled by the Makhzen were appointed at the head of their tribes by the central government. Accompanied by Mukallifs, who serve as intermediaries between the community and its sheikh/Amghar, these Makhzanian Amghars coordinate the collection of taxes in their communities with the Oumana (or Amin), entrusted to supervise financial and tax dealings of the central authority. Thus, the role of an Amghar changed from serving and representing his community to representing the Makhzen’s authority within his community. Some ambitious Imgharen, representing strong lineages within their tribes, have been able to expand their territorial influence considerably, successfully positioning themselves in front of the Makhzen as indispensable allies, to become Caïds entrusted with even greater duties within the Makhzen apparatus. Some of them were appointed to positions such as ‘l-‘Allaf Lkbir’ (the chief of armies) or Sadr Al Aadam (the Grand Vizier serving as head of government).

Warlords.. Subjugating the tribes and hacking their institutions

During the nineteenth century, European military and financial intervention increased in the ‘Sharifian Empire’, and the European powers imposed colossal debts on it following the battles of Tetouan and Isly. Also, in a context of the inability of the weak Makhzanian guich — an army composed of warring tribes and exempt from the Naibeh tax in exchange for their military service — to impose and collect new taxes, amid the growing societal hostility towards central government, the Makhzen found refuge and support in this emerging rural elite of warlords, which was capable of exerting the new duties and enforcing its new fiscal tax policy that would confiscate all the surplus value from the gerontocratic social structures and eventually lead to their ruin.

The Caïds used the Makhzen’s legitimacy to subjugate the tribal communities by force of arms, taking advantage of the influx of supplies and spoils of war by conquering new territories and looting “Igoudar”, which are fortified collective storehouses

The Caïds used the Makhzen’s legitimacy to subjugate the tribal communities by force of arms, taking advantage of the influx of supplies and creating a flow of provisions and spoils of war as they conquered new territories, looting “Igoudar”, which are fortified collective storehouses used by local communities to store annual crops and precious savings, and pillaging “Igherman”, the fortified villages of oasis communities in the south and southeast along the valleys of Darâa, Daddes, and Toudgha, confiscating their grains and treasures. They also hijacked the tribal structures and traditions to fill their treasuries, turning the ‘Frida’ from a contribution paid by the members of a community to cover their collective expenses, into a special tax they impose on a regular basis, and the ‘Twiza’ from mutual aid between the members of the tribal community in their collectively decided activities, into a form of forced labor, forcing the communities to provide men to build their Kasbahs (fortified citadels), cultivate their estates and settlements called ‘Azibs’, and chop firewood and the like... The case of the family of Glaouis, who flourished in Marrakech and the Haouz region, starting from the High Atlas Mountains where their legacy began, and throughout the South, represented the apex of “Caïdalism", as Paul Pascon called it to distinguish it from European Feudalism (Pascon, P. 1983).

The Mezouari Glaoui: From petty chieftainship to the big game

The name "Mezouari'' is an Arabization of the Amazigh term Amezouar, which means first among peers. In the context of tribal structures, it refers to the person who inaugurates the collective activities of the community and blesses them with ‘Baraka’. The Mezouari's descend from sheikh Ahmed al-Mezouari, and claim their lineage to the Sufi Sheikh Abu Muhammad Salih al-Majiri.

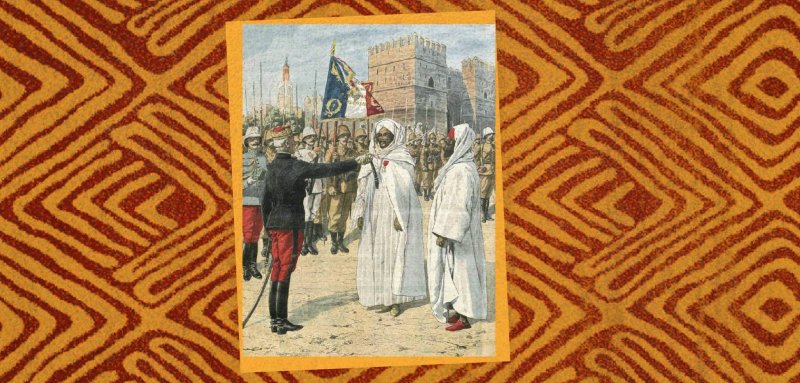

Thami el-Glaoui and other leaders played a pivotal role in the French invasion of Morocco and the campaign against the resisting tribes

The first step in integrating the Mezouari family into the Makhzen apparatus, was Sultan Abderrahman’s recognition of Mohamed Ibibat, the Amghar of Aït Ounila, as Sheikh of Aït Telouet, Aït Ounila, and Aït Toumjoujt in 1856, as an administrative subdivision under the rule of Caïd El Hachmi of Zemran, thus controlling the caravan route through Tizi n’Telouet, as well as the exploitation of a salt mine belonging to Zawya n’Taghenoust.

Satisfied with the fiscal revenues generated by Glaoui, the Makhzen of Mohamed B. Abderrahman would promote him to a Caïd and expand the territories under his Caïdat (leadership).

Satisfied with the fiscal revenues generated by Glaoui, the Makhzen of Mohamed B. Abderrahman would promote him to a Caïd and expand the territories under his Caïdat (leadership)

Ibibat would then mobilize harkat (military campaigns) against his neighbors in the south and further expand his sphere of influence as far as the Kasbah of Taourirt (present day city of Ouarzazate). After his death in 1886, his son Madani replaced him at the head of the Glaoua tribe. In 1893, while returning from a military campaign in Tafilalt, Sultan l-Hassan’s mehalla (army camp) was trapped in a snow storm in the territory of Glaoua. Everyone would have perished had it not been for the arrival of Madani and his brother Thami, who came for their rescue and hosted the Sultan and his armies in the Kasbah of Telouat for 25 days. The two brothers took advantage of the opportunity to strengthen their relationship with the palace’s influential men, especially Ba Hmad, then companion or ‘Hajib’ to the sultan.

This incident worked in favor of the Glaouis on many levels. Madani was named Khalifa (or representative) to the Sultan in the southern provinces, from Telouat to M’hamid l-Ghezlan (Bouzidi, A. 2009). After the death of Sultan l-Hassan, Ba Hmad would serve as regent and grand vizier to Sultan Abdelaziz, the young successor of l-Hassan, which reassured Madani of his position in the new hierarchy. On the military level, this meant they got to keep two cannons, two machine guns, and their munitions, as such weapons had never, until that moment, been under the control of a Caïd before. Madani would use this military advantage to consolidate and expand the Glaoui empire in the south. Beginning with his neighbors Aït Zineb of Tamdakht, he conquered the vast territories of Aït Ouaouzguit. He also carried out several attacks in the northern slope of the Atlas, reaching as far as Tazart, where he built a kasbah to cast his shadow on the eastern Haouz plain and pillage the tribe of Zemran whose Caïd once ruled the Glaoua tribe (Haouzali, A. 1992).

After the death of the powerful Ba Hmad, Sultan Abdelaziz appointed Madani Caïd of the Mesfioua tribe, which had been defeated in the 1899 insurgency. The latter built another kasbah in Imi n’Zat (present-day Aït Ourir), and the Glaoui’s access to the central Haouz plain and Marrakech was secured. The Haouz plain is a complex chessboard on which Madani and Thami will move their pawns cautiously, in a dangerous game of in fluence and power, and where other senior Caïds such as Goundafi, Layyadi and M’touggi have already secured their seats (Pascon,P. 1983).

The Glaouis’ support for the cause of the new sultan Abdelhafid opened the doors for them to hold important positions in the sultan’s Makhzen. Madani was appointed L‘Allaf Lkbir, or chief of armies, then Grand Vizier in 1909

The Glaouis would soon realize that they cannot count on the weak Sultan Abdelaziz to contain the spread of internal rebellions and counter European colonial ambitions in the country, especially after participating in a failed military campaign against the rebel Jilali Zerhouni (known as “Bou Hmara”), who defeated the Azizist armies. This also came after the Algeciras conference that granted substantial concessions to European colonial nations, as well as the French occupation of Oujda by Lyautey, the bombardment of Casablanca that caused thousands of civilian deaths, the landing of French troops and the ensuing rebellion of the Chaouia tribesmen who took up arms against the invaders. A series of moves and changing alliances in the Haouz chessboard would result in Sultan Abdelaziz being deposed by Abdelhafid, his brother and khalifa (representative) in Marrakech.

The Glaouis’ support for the cause of the new sultan Abdelhafid opened the doors for them to hold important positions in the new sultan’s Makhzen. Madani was appointed L‘Allaf Lkbir (chief of armies), then Grand Vizier in 1909. Thami held the position of Pasha of Marrakech, which gives him the authority to control the Guich tribes and their lands in the Haouz plain, one that he will keep until the end of the French colonization, aside from a brief period of time.

Allies to the colonists

The new Sultan, dubbed ‘Sultan of Jihad’, who was vocal in his hostile stance against the Algeciras treaty and the European occupation, failed to live up to his nickname and the conditioned Bay’ah (pledge of allegiance) of the religious scholars of Fes. Abdelhafid eventually signed the treaty of Fes in 1912, officially ending the country’s independence, before abdicating the throne under the pressure of the French Resident-General Lyautey. His brother Yusef was proclaimed sultan by the French and another ‘Sultan of Jihad’ would proclaim himself in the south.

After the death of his older brother Madani six years later, Thami replaced him as head of the Glaoua tribe. An ally to the French, he then helped them establish their control in the Haouz of Marrakesh

Ahmed al-Hiba was the son and successor of Maa al-’Aynayn, a Sufi Sheikh and leader of resistance against European colonialism in Trab el Beidan (the geographical area occupied by speakers of the Hassaniya dialect). Following the abdication of Abdelhafid, he considered the throne vacant and was proclaimed Amir al-Mu'minin in Tiznit, before marching on Marrakech. Al-Hiba had popular support and was seen as a savior in the Haouz and elsewhere, and so the Caïds found themselves in a weak position and had to play along; they all went to pledge their oath of allegiance to him before he entered Marrakech. Thami Glaoui, among others, was secretly coordinating with the French and kept them informed on the situation and developments in the city. French troops marched on the city under colonel Mangin, and a battle between them and the Hibist troops took place at Sidi Bou Othman, north of Marrakech. The French prevailed, and al-Hiba fled the city (Soussi, M. 1960). Mangin set up camp outside the city walls of Marrakech in Gueliz, where he received oaths of allegiance from the Caïds to the new Sultan Youssef.

Lyautey understood the importance of this alliance before he was a resident-general in Morocco, and in 1894 he wrote in one of his letters: “Instead of dismantling and disbanding the old ruling structures, rather, use them in our favor”

Thami was reinstated as Pasha of Marrakech. Then, after the death of his older brother Madani six years later, he replaced him as head of the Glaoua tribe. An ally to the French, he would help them establish their control in the Haouz of Marrakesh. The colonial powers, who in turn bear responsibility themselves for the emergence of “caïdalism”, due to the unfair and heavy taxation the Makhhzen imposed on the tribes in order to pay its debts to them, continued to collaborate with these warlords. Thami and the other Caïds will play a crucial role in the French military campaign against tribal resistance in Morocco.

Lyautey understood the importance of this alliance before he was a resident-general in Morocco, and in 1894 he wrote in one of his letters from Tonkin: “Instead of dismantling and disbanding the old ruling structures, rather, use them in our favor.” (Lyautey, H. 1920)

* Khoms: fifth; Aït Atta are composed of five fifths: Aït Wahlim, Aït Wallal, Aït Unbgi, Aït ‘Aisa Mzin, along with Aït Isful and Aït ‘Alwan, both of which compose a single fifth

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!