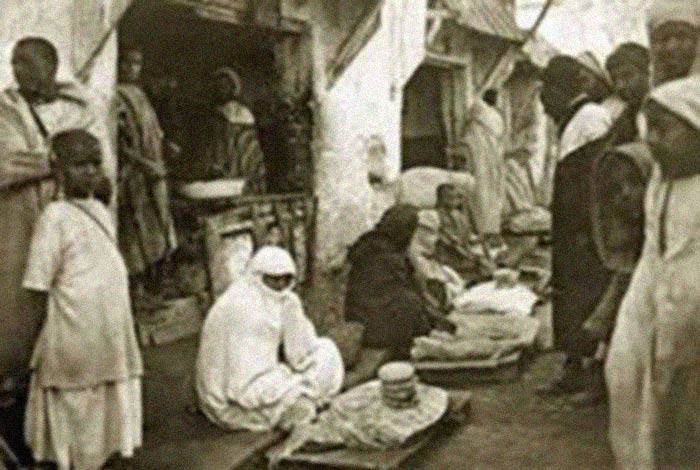

From different places and at different moments in history, Jews migrated to Morocco – attracted by everything from its cities and economic activities to the sense of security they provided.

In her book “Jews in Muslim Morocco During the 7 & 6th centuries (Hijri) - 14th & 15th (AD)”, Fatima Bu’amamah maintains that Jews in Morocco had utmost freedom in their daily lives. They lived in the largest cities and villages; they mingled freely with Muslims and had regular business with them via trade caravans; they loaned them money and even slaughtered cattle and prepared food for them.

Jews were permitted to live anywhere under the stipulation that their homes would not surpass mosques and the houses of Muslims in elevation. There was no restriction for them or for anyone else to own private property, and religious scholars granted them the right to build their own synagogues and houses of worship so long as they do not ring any bells.

The Rise of the Mallah

Later, specifically during the Marinid era (1269-1464), the kings of Muslim Morocco designated special neighborhoods for Jews near their own palaces in order to protect them. These places came to be known as the “Mallah”, which have different stories for its origin. Some owed their rise to the founder of the Marinid Empire, Sultan Abu Yusuf Yaqub ibn Abd al-Haqq, who might have moved the Jewish community in Old Fez to the Mallah neighborhood of New Fez –- or so does Mazahem Allawi al-Shaheri in his work “The Jews of Morocco in the Marinid Era (668-869h / 1269-1464): A political and Economic Study”.

This Mallah was established in 1275, after a Jewish man attacked a Muslim servant in his house and forced himself upon her in Old Fez (or ‘Fes el Bali’). The incident sparked a backlash against the Jewish community and a public outrage that would not let off until the Sultan personally intervened and moved them to their new neighborhood.

Al-Shaheri presents another account that states that Sultan Abu Sa’id Uthman Ibin Yaqub (1276-1331) built the city of Homs in New Fez, also known as the Mallah, and it was then taken as a neighborhood for the Jews, with a neighborhood for Christians nearby.

Yet, the most popular explanation is put forth by Bu’amamah, who provides that the first Mallah was built in 1438 – when the Jews of Fez were expelled from the city for “desecrating” a mosque and pouring wine in its lanterns. For their protection, Sultan Abd al-Haqq II of the Marinids was forced to move the Jews to the new capital. Eventually, similar neighborhoods began popping up elsewhere in the country in Taza, Badis, Nefza and Azemmour.

Bu’amamah mentions that Jewish references attribute the community’s relocation to the Mallah of New Fez to the discovery of the tomb of Sultan Idris I (who founded the Idrisid Empire and whose ancestry traces back to Prophet Muhammad). According to these texts, the Jews of Old Fez were expelled so “not to desecrate the pure and holy site that holds the tomb of the sultan.”

Bu’amamah adds that these Jewish sources describe the move as detrimental to the situation of the Jews who refused to abandon their shops and homes – effectively leading many of them to convert to Islam.

Security Measures to Protect the Jewish Neighborhood

The Mallah neighborhood of Fez had one point of entry attached to a two-pinned gate that was the most active one in southern New Fez. As was the case for the other Mallahs of the country, several security measures were put in place to protect it. It was equipped with two watch towers (that have since been lost), according to Hisham al-Rakik in his study “From the Vicinity of the Jew’s Hotel to the Mallah of New Fez: Manifestations of the Jewish Presence in the Urban Landscape of Fez.”

Jews lived in utmost freedom in Morocco. They mingled with Muslims and carried business with them. They lived anywhere as long as their homes would not surpass mosques and the houses of Muslims in elevation before setting up their neighborhoods known as Mallah

Additionally, a guard taskforce was appointed to the neighborhood. The Jewish community would fund it, while the state armed it with batons and rifles for days of unrest or chaos. The Mallah would close its doors at night and on Saturdays (Sabbath), as well as on Jewish religious holidays.

Despite these measures, Bu’amamah states that the Mallah of New Fez was attacked by a mob of Muslims in 1465, during which many Jews were killed after the body of a Muslim was found and Jews were accused of the murder.

Autonomy and Administrative Independence

Inside the Mallah, Jews enjoyed cultural and administrative autonomy under the stipulations of Islamic Sharia. They had their own system of jurisprudence and finance, as well as their rights to the lending system, services, education, and social welfare –according to Abdulaziz al-Saud in his book “Tétouan in the 18th Century (Power – Society – Religion)”.

Within this independence, the highest power was in the hands of the head of the Jewish community, called the Pparnas’, who spearheads a council called the ‘Khonteh’ or ‘Ma’Amad’ and enjoys complete authority.

The council consists of seven members, dubbed ‘parnassim’, who were elected under the supervision of the Supreme Pontiff. Four of the seven would be notables of the Mallah, while the remaining three would be rabbis and members of the clergy.

The council managed the day-to-day of the community from public work to cleanliness. It also controlled the financial resources derived from donations and Jewish endowments, as well as the “kosher” tax enforced on meat slaughtered according to Jewish Shariah. Moreover, the council would attend to matters of the ‘baya’ah’ (or allegiance), charity projects and education affairs. Each year, the head of the council would deliver the ‘jizyah’ (tax) to the city’s leader, according to al-Saud.

The ‘baya’ah’ represents the natural space of assembly for the community. In addition to being the site of communal prayer, it also played the role of school – as did the ‘kuttab’ in Muslim communities – and was run by three individuals.

Jurisdictionally, the supreme religious judiciary was represented by the “Supreme Rabbinical Court.” It was constituted of 3 supreme judges that looked into civic and property disputes between inhabitants of the Mallah. Meanwhile, criminal cases and disputes among Jews and non-Jews were left to a specialized judge.

Moreover, a person was appointed to the position of ‘Sheikh of the Jews’, or ‘nakid’, and was responsible for maintaining security and the overall rule of law within the Mallah. The ‘nakid’ is mainly a deputy of the chief and is appointed by the ‘Ma’Amad’ following the chief’s approval. According to al-Saud, his role resembles that of the “muqaddam” in Muslim communities, and he acts as a sheriff or policeman under the chief’s authority.

In his book “Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Morocco” (translated to Arabic by Ahmad Shahlan and Abdulghani Abu al-Azm), Haim al-Za’afarani provides that the Mallah contained a small prison reserved for the perpetrators of religious violations and for those sentenced to prison by Jewish religious authorities following the approval of state authority. The prison was guarded by an armed Muslim.

Within the Mallah, a special topographical collective was established for each trade or craft. For example, there was a “market for exchange,” whose members traded in gold, as well as a thread-making market for expensive metals like gold and silver, the Jewish community’s most successful endeavor. Members and laborers of this metal market were dubbed ‘sikliyeen’ (forgers). Moreover, Mallahs often entertained a leather market and yellow copper market, in addition to monopolizing distillation (perfume) industries and the beeswax trade.

Customs and Traditions

Jews of the Mallah would cultivate customs and engage in acts that seem to derive from the urge for self-preservation; acts like early marriage or marriage at puberty. According to al-Saud, these customs encouraged the Jewish minority to marry within and proliferate as a means of fending off its extinction.

Jews of the Mallah would cultivate customs and engage in acts that derive from the urge for self-preservation; like early marriage. These customs encouraged the Jewish minority to marry within and proliferate as a means of fending off its extinction

Al-Za’afarani, on the other hand, lends to the citizens of the Mallah a number of superstitious customs and traditions. For instance, a new purchaser of a house or shop would not sleep or use his property except after placing four pieces of ‘henna’ and lighting a candle over each one. Subsequently, he would ask the ‘jinn’ (spirits) of the place to welcome their new neighbors, before locking up and leaving the place for the night.

The following morning, the owner would return with a black rooster that he would slaughter on the spot and sprinkle its blood in the four corners of the property. The rooster’s meat would be used for a meal of ‘couscous’ intended for family members and given out to neighbors, while a little of the couscous would be thrown down the place’s wells and toilets. As for new houses, a rooster would be insufficient, and an additional slaughter of a black goat or cow of the same color is needed.

In cases of prolonged illness, or repetitive miscarriages or stillbirths for a woman, or any painful incident, Jews of the Mallah would prepare a meal for the jinn (spirits) and plead for their mercy in a ritual called “nesraa”. The meal consists of a dish of couscous prepared with black rooster meat and offered to each member of the family.

The household would eat the meal at sundown, while a large plate would be taken by certain women specialized in superstition and folklore magic to throw down slaughterhouses or the sewage waters of the city, according to al-Za’afarani.

Intellectual and Ideological Divergence

Despite all, the Mallahs were not marked by uniform intellectual or ideological homogeneity. According to Zubaidah Atallah in her book “Jews in the Arab World”, a large number of Spanish Jews migrated to Morocco between the years of 1391 and 1492, as a result of the Christian revival (following the fall of Andalusia). Having been subjected to death threats in Spain, around 150,000 Jews left Aragon, Castalla, Mallorca (Majorca), and other Spanish cities for Morocco, settling in places like Fez, Meknes, Tangier, Tétouan, Salé, Asilah, Rabat, Safi, and Tlemcen. The immigrants were more educated than the Jews of Morocco and acted arrogantly towards them, creating a cultural gap among the two.

The rift between the natives, dubbed “toshkim,” and the newcomers, called “makorshim,” grew due to the European immigrants’ intellectual and economic superiority. Public disputes concerning rituals and slaughter conditions ensued between the two communities. Ultimately, the European newcomers won the contests and were crowned leaders of the Jewish communities of Morocco.

Internal Migrations

In certain periods of history, different factors led Jews of the Mallah to move to other places. During revolts and rebellions, for instance, Jews were often forced to leave their homes by royal decree. The Jewish community were not the only victims of these abrupt orders; it was a common retaliation by the ruling class against rebellious Muslims groups.

Yet, the forced migration of Jews from areas of uprisings was often not oppressive in nature. In some instances, it was supplemented with special privileges and benefits that made the Jewish community’s life more fortunate.

Al-Za’afarani provides examples of these occurrences, such as when groups of Jews left the ‘Zaouia of Dila’ for Meknes and Fez in 1668 during the reign of Sultan al-Rashid Bin Ali al-Charif, or when Jewish citizens swarmed to Essaouira from Agadir in 1765 during the days of Sultan Muhammad Bin Abdullah.

Moreover, during times of disease and famine, Jewish groups and individuals migrated to less afflicted areas, seeking refuge with their more fortunate brethren. For instance, the Jews of Meknes fled the famine that hit the city in 1738, heading first towards Doukkala (situated between Casablanca and Marrakesh), then further south towards Dar’aa.

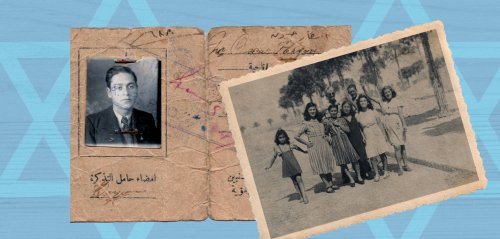

After 1956, the breakup of intricate Jewish communities began in Morocco, and a vast number immigrated. Erasure was the fate of a community that had inhabited the country for nearly two thousand years. How did the Jews of Morocco live?

According to al-Za’afarani, religious pilgrimage was another reason for the mass migrations through Morocco. Entire families would sometimes endure lengthy travel trips and expenses to reach the tomb of a saint and fulfill a pledge or prayer they had vowed before. Additionally, the travelers often disguised themselves as Muslims; men would don turbans, and women would wear headscarves to avoid bandits and harassment on the road.

Religious schools were another reason for Jewish travel within Morocco. Students would travel far and wide to receive proper devout Talmud-ian tutelage and a degree for their studies. Consequently, the students would either return to their Mallah of origin and carry on religious duties within the community or relocate to a new dwelling where their families would follow.

External Migrations

Jewish migration continued outside Moroccan borders. For many Jews coming from Spain, for example, Morocco was only a pitstop on the way to Palestine, the “promised land,” where they would go to establish Talmud schools and spend the rest of their lives. Moreover, migration persisted towards the Muslim East and other parts of the Ottoman Empire in search of better living conditions.

Additionally, persecution and an overall lack of security drove many authors and scholars to look for safer premises. Many found refuge in Western Europe, particularly in Italy and the Netherlands, while some travelled even farther west beyond the Atlantic.

Al-Za’afarani adds that communication with other Jewish communities was an integral part of the lives of Morocco’s Jews. Throughout the centuries, transnational Jewish communities maintained a steady line of communication via ‘fatwas’ (religious decrees) exchanged by the clergy, or through trade and cultural exchange, especially in the fields of literature.

Migration to Israel

After the Palestinian Nakba and the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, as well as Morocco’s independence from France in 1956, the Jewish community of Morocco began to break apart. A large majority of the community migrated. Exodus, thus, became the fate of community that had inhabited the country for nearly two thousand years.

Today, only about 20,000 Jews remain in Morocco out of the 250,000 that used to dwell in the Mallahs and elsewhere in the country. After having cohabitated with Muslims for centuries, as well as with Europeans in new neighborhoods during the 1950s, the Jews that remained now are mostly clustered in Casablanca.

While some groups took up France, Canada, and Latin America as their permanent residence, most Jews migrated voluntarily to Israel --where they set up with fellow Eastern Jews a different and separate community than that of the Ashkenazi Jews coming from eastern and central Europe.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!