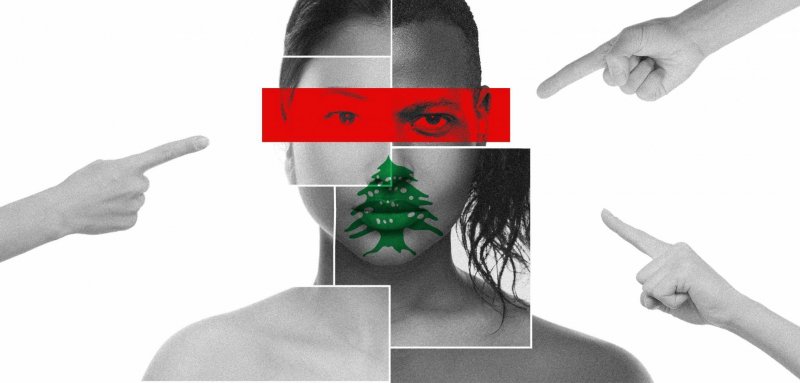

Zainab and her neighbor were in a taxi, sitting in the back seat. Ever since they got inside, the driver kept sneaking glances at her through the mirror. Then, addressing her neighbor, whose features look more “local”, and pointing to Zainab, he said, “They’re yummy.”

The word “yummy” here is a crude expression used to describe a lady as a “sexy” woman in Lebanese slang. As for the word “they”, the driver here is referring to black women in a racist stereotypical judgment that’s common in Lebanese culture.

Zainab Kanaan, 28, was born to a Lebanese father and a mother from Sierra Leone. That day, she felt twice as humiliated when the driver received a smile in response from her neighbor, instead of rising up to defend her. She felt like she was completely unable to defend herself or take on yet another new racist comment that’s been added to what she is used to encountering in her everyday life.

Zainab was born in Sierra Leone and came to Lebanon in 1997 when she was only four years old. She had moved to live with her paternal grandparents, and neither her mother nor her father had come with her, as they had been separated at the time. Zainab has siblings from her mother who she is in regular contact with, but has not yet been able to visit them.

George Floyd in Lebanon

In 2020, the American police killed a man named George Floyd in Minneapolis. His murder led to the start of a widespread popular campaign in the United States denouncing racism against black people and the discriminatory practices of the American government, under the title “Black Lives Matter”, or BLM for short.

Floyd’s case captured the attention of the entire world, as did the ensuing campaign condemning racism, and activists from all over the world were soon interacting with the cause, expressing their rejection of other forms of racism in their countries as well.

Zainab Kanaan, a journalist in her thirties, found herself standing in the shadow of this campaign of sympathy and compassion, faced with double standards: she, who has been subjected to racism without the support of even the people closest to her, is witnessing today sympathy for a victim on another continent.

It was then that she decided to express what she was experiencing in a long Facebook post. She wrote: “Ever since the events in the United States began, I have been silently watching the outpouring of posts and the Lebanese love for Africans and black people... These actions are provocative. They are provocative to us, and not as some simple provocation, but rather a hurtful provocation — a provocation that reminds us of painful events that we have carried with us from our childhoods and still remain within us to this day…”

In 1979, the United Nations designated the week of 21–27 March as an international week against racism. Dubbed the Week of Solidarity with the Peoples Struggling against Racism and Racial Discrimination, it is observed in memory of the Sharpeville massacre that was committed by the forces of the apartheid regime in South Africa and left dozens of victims dead and wounded.

In Lebanon, there is no apartheid, as was the case in South Africa. The authorities do not kill black demonstrators, and there are no laws that designate schools for whites and blacks, or prohibit the latter from taking a bus or visiting a café because of the color of their skin.

But racist practices continue to be very much present, and are protected from any punishment or deterrence. For instance, the owners of tourist resorts do not hesitate to forbid Africans from using their swimming pools, basing this on the horrid belief they have that they are only preventing domestic workers from going in. It seems that in their minds people with dark skin are only inside Lebanon to provide domestic work and service. Thus, caste distinctions intersect with racism and manifest in its most horrific forms.

That’s not even the worst part. The worst is the number of deaths of domestic workers of African and Asian nationalities that go without any prosecution or legally trying the kafeel (local sponsor). In 2008, Human Rights Watch (HRW) issued a report stating that a worker dies every week in Lebanon, from unnatural causes. Death by suicide and falling from high buildings while trying to escape from employers were at the top of the list of the causes of death.

Violations of the rights of domestic workers often take place without the abusive employers being held accountable. Speaking on the reasons for this, the Communications Specialist & Advocacy Officer at the Anti-Racism Movement (ARM) organization, Farah Baba, tells Raseef22 that according to the law, whoever precedes the other in filing the complaint would have his case considered. Often the employer goes first to file a complaint against the worker for theft, to pre-empt any thing she might say about her being beaten, sexually harassed, assaulted, or any other form of violence, knowing full well that it is difficult for the worker to leave the house of her employers. Most of them do not even have a weekly day off and do not have freedom of movement, in addition to the fact that sponsors are allowed to confiscate their identification papers.

And if the worker was able to go file a report against her abusers, she is usually met with mockery, and often, they do not believe her in the reporting centers and think that she is the culprit. Sometimes, they tell the plaintiff that if she does report and loses her sponsor, she will face a residency problem, and her stay in Lebanon will become illegal. Sometimes recruitment agencies or her employer even threaten her with her salary. All of these reasons prevent the violators from being held accountable, explains Baba.

Black Alienation

In January 2022, social media in Lebanon was awash with racist posts, within the context of a campaign launched by supporters of Hezbollah against media figure Dalia Ahmed. Twitter users directed hate speech towards her online because of the color of her skin, so she addressed them in a video message, where she said: “Who told you that I present myself as someone blonde with blue eyes? Who told you that I am not proud of my color that God gave me?”

Zainab experienced many incidents in her childhood that she still remembers. She heard children whispering about her looks and asking, “Why is she black?”, “Why is her hair like that (curly)?”. On one occasion, things went beyond these questions, so far as to reach the point of cruel insult, when a child of her same age called her a “negro” while fully aware that it was an offensive word.

It didn’t stop with her child friends. She used to hear insulting expressions coming out of the mouths of adults, some of whom were members of her extended family. Zainab tells Raseef22, “They used to say, ‘Her mother is a black ‘abdeh (slave)’. Maybe as a child, I did not understand the exact meaning of the word, but deep down, I felt that it was a derogatory term.”

The most difficult thing I experienced during my childhood was the feeling that I was invisible, since most of the students in the school did not approach me or play with me. I used to feel lonely, and sometimes they would beat me and call me Sri Lankan.

Zainab notes that it is common for Lebanese people to say that Africans are “slow as a people”. She says, “When I would get angry and object to such crude descriptions, they used to say that I had nothing to do with what they are saying, because I’m Lebanese.” Of course, such a reply would not convince her. In addition to being a justification that perpetuates the racist notion and intent in general, it also specifically and personally touches her, “My mother is African and I feel that I am part of these people — that is, Africans — and that I belong to them and identify with them, and this is something that cannot be denied or canceled by the fact that I grew up and lived my entire life in Lebanon.”

Of course, Zainab’s experience with being half-African did not stop at racism based on appearance, There’s an additional level of racism that comes with being a female born of an African woman. She found herself hearing statements like she should thank God that her father brought her to Lebanon to live and grow up there instead of living in Africa, because she would automatically become a whore there. The same people used to say, “The mothers of African children are whores. That is why they do not come to live with their kids, and this is the justification that drives the father to send his children to live with their relatives instead of keeping them with their mother.” In the eyes of the Lebanese family and in their account, “African mothers are always the guilty culprits,” she says.

Later on, throughout her teenage years, Zainab experienced being seen as someone who isn’t beautiful. She recounts, “I suffered for being seen as someone unworthy of love, rather I was only seen as a sexual object.” These stereotypical patterns, which intensify a young lady’s feeling of insecurity in an already conservative society, made her stay “in a constant state of defensiveness.”

Zainab, who used to hear comments that automatically criminalize her mother just because she’s African, wishes, “If only I had grown up by my mother’s side, I would have at least felt that there was someone I identified with and looked like. Things would have been easier for me as a child at the very least.”

Zainab’s story is not an isolated event. It’s the same story for every person whose skin color differs from that of the majority in Lebanon. Both Nasser Bazzi, a Lebanese young man, and his Ethiopian wife Aisha, are very well aware of the nature of society here. They have experience with racist practices on an almost daily basis from the time they fell in love till after the birth of their first son. Today, when they think about their son’s future, they feel that moving to another country would be the most appropriate solution.

Chinese/Japanese

Saeb Kayali, 32, was born in Lebanon to a Lebanese father and a Thai mother. His parents met in Lebanon, after his mother had run away from a marriage that was being imposed on her.

Saeb majored in the field of advertising and communication at the Lebanese International University, and in 2019 he moved to Dubai, where he now works in media.

The 30-something young man tells Raseef22 that he was at a very young age when “I discovered and felt that I was different from the rest of my friends, and the reason was the nickname they gave me: ‘Chinese (or the Chinese kid)’.” He remarks, “It was an upsetting nickname, simply because I'm not Chinese, and because I didn’t pick that nickname.”

He sees that what he has experienced in most cases reflects the ignorance and shallowness of those who are making the comments, and not just a feeling of superiority or racist intent. On this, he says, “What makes me angry about being called ‘Chinese (or the Chinese kid)’ is that my friends who were born to foreign mothers with white skin, blond hair, and colored eyes, have never been given nicknames by anyone based on their other nationalities. They were not called the ‘Swede’ or the ‘German’ for instance. On the contrary, everyone sees them as good-looking.”

Despite the comments he used to hear at school and amongst his friends, Saeb considers himself more fortunate than others because his family is from the middle class and he was able to attend a private school, “not because the poorer classes tend to be more racist, but because the classrooms at school were small, with each including only around 12 people, and the same students remain, unchanging from year to year, which helped me form friendships between me and them.” This prevented him from hearing too many racist comments.

In his opinion, “racism is not just directed towards color, but also towards social class. The poor encounter it far more than the rest, especially foreign workers in Lebanon.” He recalls a trick he and his friends used to play for fun when they were kids. They used to claim that he was the son of the Thai ambassador in Lebanon, and “as soon as we would mention this piece of information I would feel that attention and interest in me would double in a positive way. But let’s imagine what the response would be if I was just a worker.”

“I learned how to take advantage of society’s interest in my facial features and take advantage of the issue” he recounts, adding, “When I was looking for a job during my first days of university, I applied for a job in an Asian restaurant that serves Chinese food, and the man hired me right away even though I had no experience in this field. I continued to work in a number of Asian restaurants that would hire me right away,” before he traveled to Dubai to work in his field of specialization.

But Saeb’s private life was not without any upsetting comments. “My girlfriend’s mother used to express her concern that her daughter’s children would have ‘Chinese’ features. Although she had affection for me, this did not change her view of our relationship,” he recounts. The relationship did not continue anyway, and the reason they separated was not because of his features or identity.

Saeb remembers two stories really well because of how much they left an impact on him. They took place when he was working in a shopping mall in Beirut. He relates, “When the children would see me, they would pull their eyelids in order to mimic my features.” He then adds that “some customers didn’t even address me, as if I wasn’t there, and when I would try to interact with them, they would show surprise that I speak fluent Arabic, so I’d have to tell them that I was Lebanese.”

When she saw how the killing of George Floyd sparked everyone’s sympathy, Zainab felt the double standards. She, who has been subjected to racism without any support, witnessed sympathy for a victim on another continent

Having to prove his Lebanese identity has always created confusion for Saeb. These issues generated in him “great hatred towards Lebanon, for I do not belong to this country as a country, but rather to a small group of people I love, and to some places.” Even in these places, his memories in them conflict, and some of them anger him greatly, especially when it comes to the treatment of foreign workers in Hamra Street.

“I think that this is how my mother is treated too,” he says, adding that, “I feel great sympathy for them and try to take the initiative to help them if I feel that they are lost or are in need of someone in a foreign country.” He does not remember specific stories where his mother was subjected to racism, but he is absolutely certain that she encountered many looks of superiority, because she was a worker in Lebanon. He feels like she didn’t often go out with his father and his friends because of her nationality.

Today, Saeb lives in a city that embraces a wide diversity of nationalities and ethnicities. Despite this, he still hears surprised comments over how he is Lebanese and speaks Arabic, especially from the Lebanese people residing there.

Racism as a political phenomenon

Farah Baba sees that “racism is a social, cultural, and economic phenomenon, and it is a political phenomenon first and foremost. The overblown concept of the Lebanese identity and its advantages have exacerbated the feeling of superiority towards foreign workers.”

Speaking on the Lebanese identity and its roots, Lebanese researcher and feminist activist Farah Kobeissi considers that racism in Lebanon has roots that go back to the founding thought of the State of Greater Lebanon, which focused on the fact that the Lebanese people are very distinct from their neighbors, and this is something that is not true in her opinion.

Racism in Lebanon is rooted in the charter of the State of Greater Lebanon, which focused on the fact that the Lebanese people are very distinct from their neighbors, a fallacy at best.

“In the lens of the prevailing ideology, some of the neighbors were seen as ‘backward’, ‘bedouin’, or ‘rural’ people, and they were therefore considered less cultured and knowledgeable than the Lebanese people, and even inferior to them economically and politically as well... Lebanon’s founding thought formulated its standards on these social foundations,” Kobeissi tells Raseef22, adding that “this ideology still exists to this day, in political, institutional, and media discourse, which still has effects on foreign workers, migrants, and refugees in the form of daily racist practices.”

In Kobeissi’s opinion, “As a political tool, racism attempts to control the Lebanese interior as well, and not just draw an image of the other. It tries to limit any common progressive or libertarian aspirations between the people of Lebanon and their neighbors. It is also a class weapon against migrant workers to keep a stronger grip on their exploitation and control, in order to ensure the flow of money to the rich and the bourgeoisie, and this immigrant labor (workforce) is a tool for the continued flow of this money.”

She refers to some of the numbers and statistics she had reached during the course of her research work, which show that “more than 50% of the working class in Lebanon are immigrants, and most of them are there unofficially and work without any protection, and social or health security.” She adds that “what allows the continuation of this exploitation is the reinforcement of the idea that there is a surplus of immigrant workers that are not needed, and the aim is to reduce the value of their presence and the work they do.”

For her part, Farah Baba notes that racism has worsened after the economic crisis, “especially by political officials who have found it easy to blame all the country’s misfortunes on foreign workers and incite against them with statements like they have taken the jobs of the Lebanese people, and that they are paid more in dollars than the Lebanese citizen.”

She points out that “the actual change is not only through amending the laws that legalize racism, but also through education. Work has been previously done in this regard and has brought good results, as some young people and children have become more aware of the concept of racism.”

She speaks of the experience of training students around 16 years of age by the Anti-Racism Movement (ARM) where she works. The movement is aimed at eliminating all forms of racism and repealing unfair laws against foreign workers. She notes that “many of the participants were shocked by some information on the kafala system and began to ask themselves about things that had been previously self-evident to them,” and after learning about the prejudice and unfairness that domestic workers are subjected to, how they do not even get a day off, how no specified work shifts are set for them, and how some of them do not have their own bedrooms, they began to question their parents and families.

Baba concludes that “educating the young and raising them on some basic principles helps the community reduce racist practices.”

Forbidden from swimming

The stories of banning people of color from swimming with the rest in private pools is perhaps the practice that gets the most media coverage.

Rania Jamal, 22, is the daughter of an African mother and a Lebanese father. She does not know her parents, having grown up in the Islamic Orphanage. The true story of her parents and their nationalities is not even that clear to her. Everything she knows about her family is based on the assumption that she’s the product of a relationship between a Lebanese man and an African woman that led to her birth and her father’s refusal to officially recognize her.

Rania remembers that she was only 12 years old when she went with her friends to a private swimming pool, and as soon as she got into the water, an employee ran towards her screaming that she could not go in. This shocked her, so she asked, “Why?” The answer she got was, “(Domestic) workers are dirty because of the housework they do.” The employee assumed that the young child was a domestic worker because of the color of her skin, and did not hesitate to insult her and all other domestic workers along with her.

This form of racism was experienced by Zainab in the educational sphere. She remembers one time how a discussion about foreign workers was opened in a university class during her first year when she was studying journalism at the Lebanese International University in Tyre, in South Lebanon. Most of the students’ comments contained racial stereotyping that include things like, “They are dirty and smell bad, and they should not be allowed to swim with other people.”

On that day, “I blew up in anger at them, and in response, one just directed his racism to insult me, and said that I had been repressed for a long time and now exploded in anger because of this.” Zainab says that after receiving such a response, she felt that she was merely in a useless cycle of discussion, and that no matter how much she tried to tell them how harmful their comments were to people of her color, it did not really matter to them.

Rania studied nursing, and did professional training for three years in different hospitals in Lebanon, but today she is unemployed due to Lebanon’s economic situation. Throughout her professional training, she was exposed to many racist situations that prompted her to stop practicing the profession that she had specialized in, and move on to working on her hobby of dancing, which she aims to find a job in.

Some patients had been refusing that she help them and were asking that she be replaced by a white nurse. Others thought that she had come in to clean the room and would then be surprised that she was a nurse. Whereas some told her that he “has a Sri Lankan” like her at home who helps him with the housework, she tells Raseef22.

“These experiences made me stop practicing the profession of nursing and never go back to it,” she says. Before entering the work field and even before her teenage years, the most difficult thing she experienced during her childhood was “the feeling that I was invisible, since most of the students in the school did not approach me or play with me. I used to feel lonely, and sometimes they would beat me and call me a Sri Lankan.”

Rania’s struggle with racism in her childhood is manifested heavily in actions loaded with plenty of violence against her, “My classmate used to wash her hands after touching me, and when anything from the class went missing, I would be automatically accused without reason or justification, and this is something I never once did.”

“All of this made me not want to go out or mingle with the outside world. Even my freedom to be in public space was taken away from me.” This is how Rania explains her desire to isolate. When she would commute out in public, she used to face many questions and surprise that she speaks fluent Arabic.

On one occasion, “the taxi driver offered to secure me a job at a house through a recruitment agency he manages, and when I told him that I am not a domestic worker, he did not care and insisted on continuing his conversation,” Zainab recounts. She then comments angrily, “The majority do not believe that I am Lebanese, some think that I exaggerate when I talk about what I’ve been through, but all this, and more used to happen, and only people like me will know what I’m talking about.”

Today, when Rania sees dark-skinned children, she says that she feels sorry for them, because she already knows the hardships they currently face and will face later on.

In 2020, following the murder of George Floyd, Rania and a group of people tried to raise awareness against racism, so they organized a sit-in in front of the American University of Beirut in solidarity with Floyd, but they were mocked. Currently, she says, she has lost all hope of making a difference at this level. “Today I just want to leave Lebanon because I do not belong to it. I tried my best to stay, but staying is very difficult.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!