A smile is the simplest way to say hello, it’s a greeting, a signifier of polite behavior and is often accompanied by pleasantries. Smiling is a form of communication that transcends languages, cultures and backgrounds. Authors from all over the world have written in praise of the smile, in Othello, William Shakespeare wrote, “the robbed that smiles, steals something from the thief” and Mark Twain said, “never regret anything that made you smile”.

In the Bible, “a cheerful look brings joy to the heart” (Proverbs 15:30), and in Islamic teachings, the smile is considered a form of worship, a sunnah of the prophet Muhammad, who said, “Smiling in your brother’s face is an act of charity”.

In the Bible, “a cheerful look brings joy to the heart” (Proverbs 15:30), and in Islamic teachings, the smile is considered a form of worship, a sunnah of the prophet Muhammad, who said, “Smiling in your brother’s face is an act of charity”

In popular culture, smiling is considered a form of flirtation and many songs and poems have been written in praise of the smile. People across an extremely wide diversity of views and positions have written about the smile. Most notably, renowned Lebanese poet Elia Abu Madi’s He said the sky is bleak and grim, where he writes, “Smile as long as a short span separates you from death; For once dead, you will not smile again” and Egyptian revolutionary, educator, author and poet Sayyid Qutb’s poem Smile, where he writes that “you are only created to smile”, and concludes with the uplifting instructions to, “smile how you want and rejoice”.

In cinema, several Arabic films have been centered around the smile, such as Dami wa Dumou’i wa Ibtisamati (My Blood, Tears and Smile), Edhak Elsoura Tetla’ Helwa (Smile, So the Picture Looks Good), and Alazab Fawq Shefah Tabtasem (Agony Over Smiling Lips).

Why then, is it rare to see smiles in the history of Arab art?

Smiles are rare in the history of art, “in the long history of portraiture the open smile has been largely, as it were, frowned upon,” as Nicholas Jeeves writes in his essay, ‘The Serious and the Smirk’, exploring the history of the smile from Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa to Carravagio and Alexander Garner’s photographs of Abraham Lincoln. He describes the mouth in the history of portraiture as a site of heated debate, “an ongoing conflict between the serious and the smirk”.

Julia Fiore offers an interesting perspective on this in her article ‘Why are smiles so rare in art history’, she writes, “we might at first think that Westerners of centuries past refrained from smiling for portraits to avoid showing off their bad teeth. In fact, poor dental hygiene was so common that it wasn’t considered a detractor of attractiveness”.

There is a belief that laughter precedes evil and superstitious people often follow their laughter with a prayer, hoping their laughs were not a bad omen

Julia Fiore’s article exploring the rarity of the smile in the Western canon via Nicholas Jeeves inspired me to look into possible reasons pertaining to the Arab world.

Laughing for no reason is a lack of good manners

A number of colloquial sayings frame laughter negatively, there’s a popular saying in Arabic that ‘laughing for no reason is a lack of good manners’. Children are scolded with this line for being rude; laughter and smiles can often be considered disrespectful, especially towards elders, or in formal settings.

There is also a belief that laughter precedes evil and superstitious people often follow their laughter with a prayer, hoping their laughs were not a bad omen. There’s no clear timeline for how long these beliefs have held true, but they can serve as an explanation for the attitude towards smiling and why a subject would opt not to smile for their portrait.

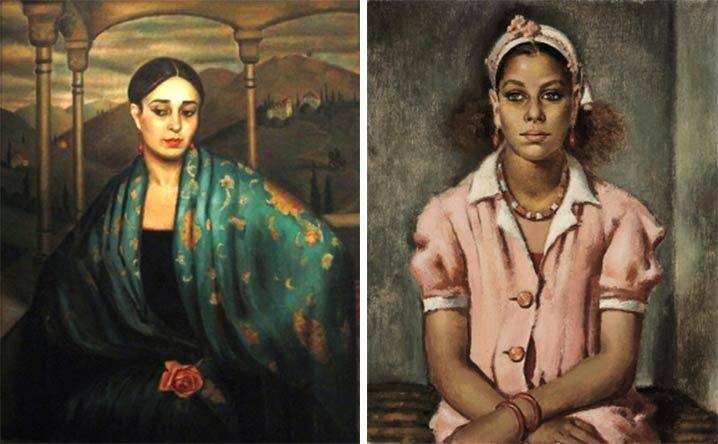

Mahmoud Said’s My Wife in a Green Shawl, 1924 and The Girl in the Pink Dress, 1945

In most of his portraits, Mahmoud Said (Egypt, 1897-1964) depicts deeply expressive, yet unsmiling subjects. My Wife in a Green Shawl, 1924 (in the Mahmoud Said Museum’s collection) and The Girl in the Pink Dress, 1945 (in Mathaf’s collection) are no exception.

Jewad Selim’s Portrait of a Girl, circa 1950s and The Gardener, 1950

Similarly, Jewad Selim (Iraq, 1919-1961) painted many striking subjects without smiles. His Portrait of a Girl portrays a young girl looking thoughtfully ahead of her, with an air of mystery and vague ennui, whilst his portrait The Gardener shows an emotive, more stylised figure, with deeply evocative eyes.

Sitting for a portrait is a long and strenuous process

Nowadays, it takes a few seconds to smile and snap a selfie, whereas posing for an artist to paint a portrait is a lengthy and strenuous process for everyone involved. The process differs based on the artist’s practice, but in most cases, it involves hours of sitting in relatively the same position and it would be impossible to hold a smile for the entirety of that time. More often than not, the subject chooses a pose they are comfortable with, in a natural setting to support the long hours of trying not to fidget.

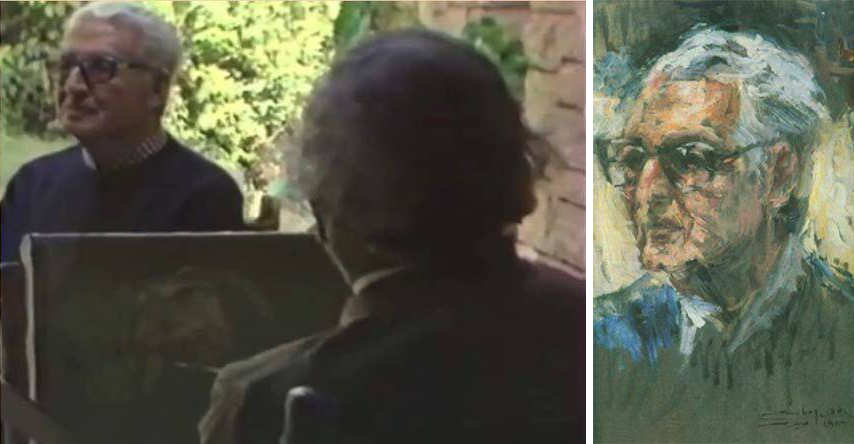

Still, Sabry Ragheb painting Ihsan Abdel Koddous, 1983, Portrait of Ihsan Abdel Koddous, 1986

In this still from a program that aired on Egyptian state television, Sabry Ragheb (Egypt, 1920-2000) paints a portrait of Ihsan Abdel Koddous, writer, novelist, journalist and editor at Egypt’s Al-Akhbar and Al-Ahram newspapers, in 1983. Throughout their session, you can see Ihsan Abdel Koddous smoking his cigar and moving around to an extent, all the while sitting comfortably in a natural pose. The finished portrait is dated 1986, implying that the artist may have taken his time finalising the work.

Hussein Bicar painting a portrait in 1983 and Untitled, 1973

In this still from a short film that aired on Egyptian state television, Hussein Bicar (Egypt, 1913-2002) paints a portrait in pastels. Throughout their session, the sitter is visibly restless, and appears to be strained as he attempts to sit still, it’s a wonder Bicar was able to capture his likeness. Hussein Bicar’s practice involved experimenting with a variety of styles, he painted many portraits, many of which depicted grave faces.

A portrait without a smile offers more opportunities for creative expression

When you see a portrait of someone smiling, you’re immediately drawn to the smile. It can capture a sinister expression, a smirk, or a demure demeanor, but there are limits to the depth of personality that can be portrayed with a smiling sitter. A straight face or vague expression can offer an air of mystery, and can allude to many different aspects of a subject’s personality that can be open to interpretation.

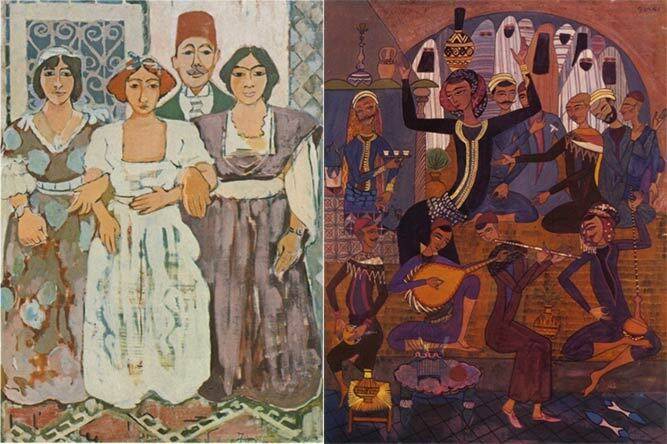

Zoubeir Turki’s Family Portrait, 1962 and Abdelaziz Gorgi’s Moorish Cafe, 1964

In these colourful scenes from Tunis, Zoubeir Turki (Tunisia, 1924-2009) offers a bleak-faced family portrait that captures the characters of each member of the family in the slightest details, whilst Abdelaziz Gorgi (Tunisia, 1928-2008) depicts a vibrant musical gathering where all in attendance seem entranced and lost in their own worlds. At first glance, one of them may appear to be smiling, for the angle of his moustache, but along with his companions, his eyes are fixed in a captivated stare ahead.

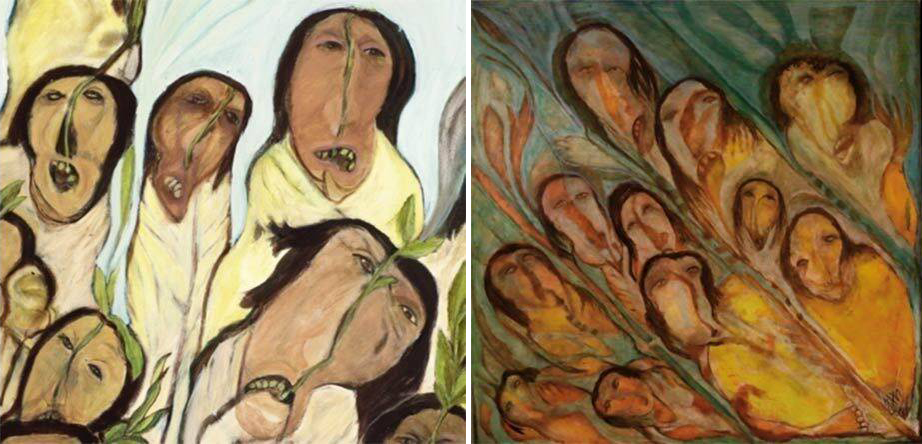

Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq, Preparation of Incense - Zar Ceremony, 2015 (detail), and Untitled, 2015

In this detail of Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq’s (Sudan, b. 1939) Preparation of Incense - Zar Ceremony and this Untitled work, the women’s faces are distorted, their mouths twisted into a variety of expressions to reflect a multitude of emotions and mental experiences, in a style characteristic of Ishaq’s practice.

Serious subjects and somber expressions

The regions of the Arab world have long been sites of political upheaval, wars, conflicts, and revolutions; resulting in serious subject matter that many artists from the region have grappled with. As a result, many subjects are portrayed with pensive and somber expressions to reflect their various contexts and surroundings.

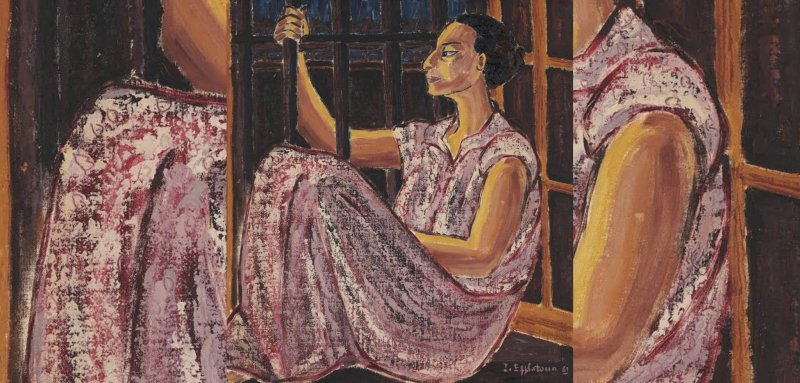

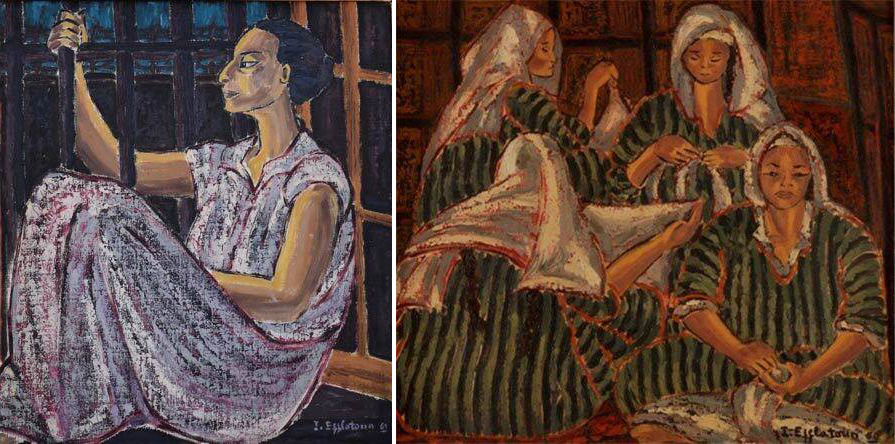

Inji Efflatoun’s Dreams of the Detainee, 1961 (in the Barjeel Art Foundation collection) and In the Women's Prison, 1960

In these paintings from her prison series, Inji Efflatoun (Egypt, 1924-1989) depicts the miserable conditions of her incarceration. Efflatoun’s paintings often portrayed political themes and struggles in Egypt’s society, and as a result most of her subjects appear burdened and unsmiling.

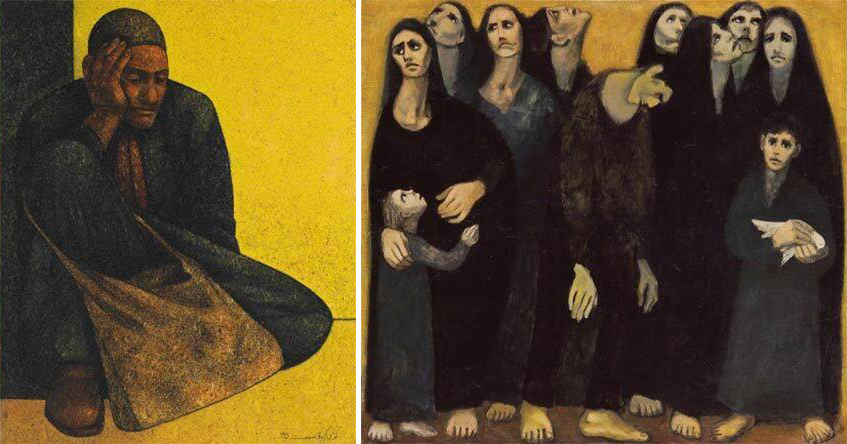

Louay Kayyali’s The Resting Beggar, 1974 and Then What, 1965

Similarly, Louay Kayyali (Syria, 1934-1978) was inspired by the social and political aspects of his surroundings. He painted many solitary figures, like this resting beggar, who looks weary; asleep with a furrowed brow. In an earlier composition depicting Palestinian refugees titled Then What, the subjects appear miserable and anguished, barefoot and disjointed.

To be taken seriously

Unlike the academies of the western canon, academies of fine art were only established in the Arab world by the mid 19th to early 20th Century. Prince Yusuf Kamal, patron, arts enthusiast and a member of the Egyptian royal family opened the School of Fine Arts in Cairo in 1908, during which time painting in the wider region remained within the Ottoman traditional style.

Unlike the academies of the western canon, academies of fine art were only established in the Arab world by the mid 19th to early 20th Century

Art in Tunis was the first art school to open in North Africa in 1923, while in the early 19th century, artists in Iraq, Jordan and Palestine were largely self-taught due to the circumstances of their occupation. Most countries of the Arab world gained their independence from French and British colonial rule in the mid 20th Century and this paved the way for the development of modern Arab arts movements. As these movements developed, it was difficult to be taken seriously as an artist. To be taken seriously, artists would paint serious subjects.

Untitled, 1967, My First Teacher George Aliyev, 1960

Muhanna Durra (Jordan, 1938-2021) experimented with many artistic styles, throughout his oeuvre, he painted works that reflected his mood. His portraits are brimming with emotion, and most of his subjects appear deep in thought and unsmiling.

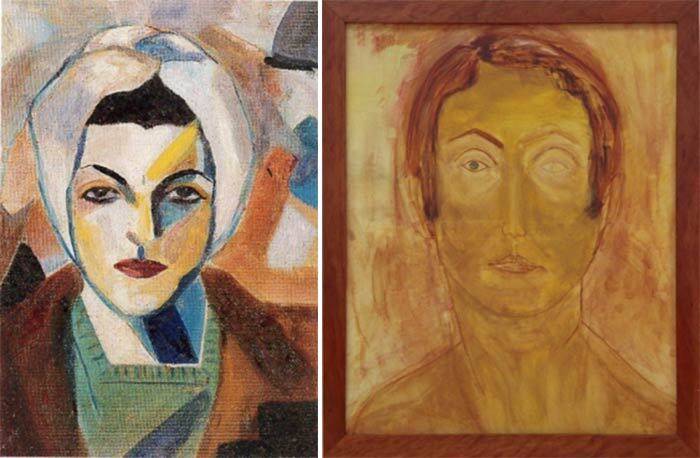

Saloua Raouda Choucair, Self Portrait, 1943 and Huguette Caland, Self-Portrait, 1967

These self portraits by leading Lebanese ladies Saloua Raouda Choucair (Lebanon, 1916-2017) and Huguette Caland (Lebanon, 1931-2019) depict the serious gazes of these artists. Throughout art history, few women artists were successful and gained recognition during their lifetimes, compared to their male counterparts. Choucair and Caland’s serious faces can be seen as a reflection of their determination and resolve.

The advent of photography and the emergence of the smile

With the advent of photography in the mid-19th century the smile became an easier feature to include in portraiture, in fact Julia Fiore writes that it “became a standard part of the portrait”. In the Arab world however, it took some time for the smile to be a preferred feature in a photograph. People posed with serious expressions to appear respectable. In the historical fiction series Aho Da Elli Sar (Once Upon a Time), several characters in mid-19th century Alexandria are eager to be photographed at their local studio, with a straight face, explaining that they shouldn’t smile in their photographs so that when they are no longer around and people find their photos, they would think they were serious and important (as opposed to silly and unimportant).

The Yasser Alwan Collection, Akkasah: Center for Photography, AD-MC-002_ref85 (1926), ref99, and ref118 (undated)

In these images from the Yasser Alwan Collection, at NYU’s Akkasah: Center for Photography, the subjects all appear unsmiling, dressed up and dapper, looking off towards the distance, in the typical fashion of photography during this time.

Later on however, this attitude gradually shifts - a shift captured in the film Edhak Elsoura Tetla’ Helwa, where Ahmed Zaki’s character Sayed takes his job as a photographer very seriously. People from all backgrounds and classes would get their photographs taken at his studio. He felt a great sense of responsibility to always make them look their best, and would ask them to smile to get a good photo. As this attitude shifted with photography, the smile started to appear in portraiture as well, though still not so frequently, in rare instances.

The Woman with Golden Locks, 1933 (in Mathaf’s collection), Louay Kayyali, Aysha Kayali, 1952 and Mahmoud Said, Mr. Ahmed Mazloum’s Wife, 1936,

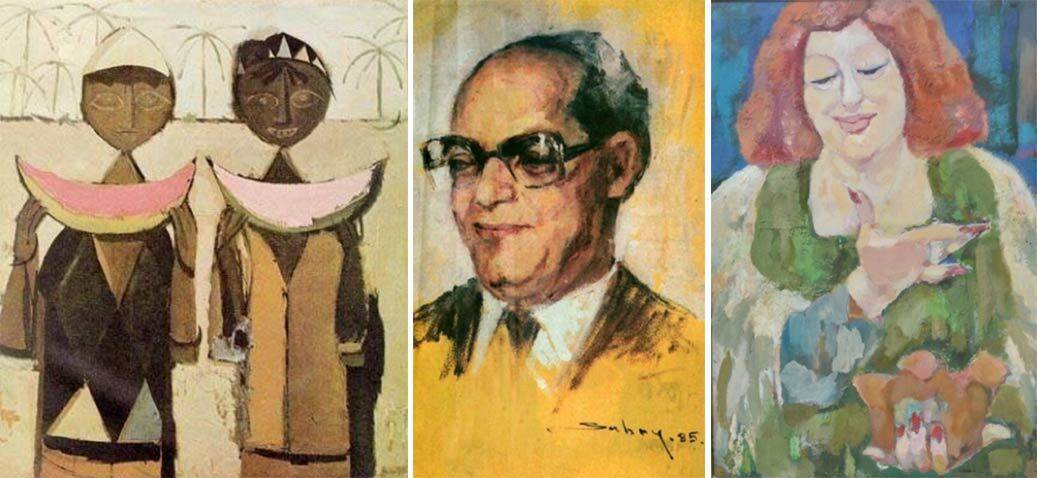

Jewad Selim, Untitled (Boys with Watermelons), Sabry Ragheb, Louis Awad, 1985, and Zoubeir Turki, Hôtesse, 1995

The same artists who mostly painted unsmiling portraits also painted a range of gleaming smiles; from Mahmoud Said’s portraits of Egyptian women, to a rare smiling portrait by Louay Kayyali, Jewad Selim’s smiling boys with watermelons, Zoubeir Turki’s gracious hostess and Sabry Ragheb’s portrait of Louis Awad’s polite smile.

It’s interesting to see that throughout art history, the smile is a rare feature of portraiture, regardless of social and cultural backgrounds. Perhaps this offers an explanation as to why it can be at times intimidating for some people to step into a museum or gallery. However, a closer look reveals many hearty laughs, smirks, grins, and smiles that brighten up the Arab art historical canon.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!