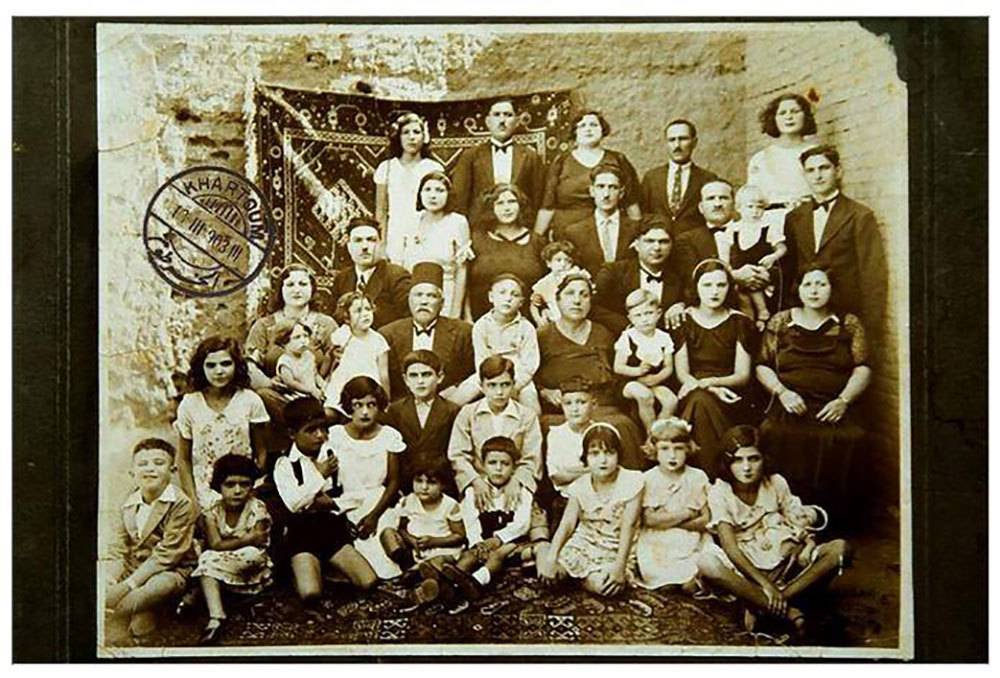

The Jews of Sudan were once known as "Binyamin", having arrived in Sudan as refugees in the late nineteenth century and settled in the city of Omdurman. They lived in the al-Musalama neighborhood of the city, and built the first Jewish synagogue in the capital Khartoum in the year 1889. It was during this period that the first association of the Jewish community emerged under the leadership of "Ben Costi", the son of a Jewish rabbi of Spanish origins. The majority of the community left the country in 1948 after the foundation of the State of Israel towards Nigeria and Tel Aviv. Today, 70 years after their exile from Sudan, the Minister of Religious Affairs and Endowments in the new Sudanese government, Nasr al-Din Mafrah, has invited Jews to return to Sudan.

The Sudanese minister – who has since been subject to many accusations, including flirting with Israel and calling for the normalization of ties with it – pledged to "reconstruct synagogues and Jewish places of worship." In a television interview with the Saudi Al-Arabiya TV channel conducted on the 6th of September, Mafrah called on Sudan's Jews who left the country to return home, affirming that citizenship is the basis of rights and obligations, and that "extremism lies not in calling on a citizen to return to their country; rather, extremism consists of refusing such an invitation." He added: "The new Sudan welcomes everyone under the purview of a civil state."

Several questions now arise: namely how will Sudan's former Jews respond to this invitation? Furthermore, what were their historical origins, and why did they leave the country in the first place?

On Sudan's "Binyamins"

In an interview with Raseef22, Khaled Fahmi, a researcher in African affairs argued that the Sudanese minister's call should not be considered as a form of flirtation with Israel, as some have argued, but an expression of the new Sudan, whose officials are attempting to construct a homeland that accommodates all of its citizenry across their various beliefs, religions and ideologies – an endeavor which if successful will make Sudan a special model in the region.

To understand Mafrah's intellectual and political background, it should be noted that he belongs to the Ansar Sufi religious movement in Sudan which the National Umma Party was born out of. Mafrah used to be a sermonizer in the Ansar mosque in the city of Rabak – the capital of the White Nile valley; in other words, the current minister is both a politician and religious figure at the same time.

Fahmi believes that it is unlikely for Jews to return to Sudan during the current period, noting that periods that follow revolutions and popular uprisings are often followed by times of chaos which often endanger religious minorities. Nonetheless, Fahmi believes that if Sudan stabilized in the next few years, Jews may start to consider returning to the country, if only for short visits to discover their roots. This Fahmi says is because the new generations of Jews of Sudanese origins now have their own lives in different countries, which are difficult to abandon in order to return to a country that is still experiencing the aftereffects of the popular uprising that brought down the former Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir.

How will Sudan's Jews respond to a recent invitation by the Minister of Religious Affairs to return to their country? Did they belong in Sudan in the first place?

The Jews of Sudan were "Sephardim": descendants of Jews once living in Spain before persecution and expulsion after the fall of the Granada, the last Muslim Kingdom in 1492

Fahmi adds to Raseef22 that before the year 1948, Jews had become a de facto reality of Sudanese society, and were not subject to any harassment – indeed, founding the "Jewish Sports Club of Khartoum" and additionally enjoying their own sports team – named "Maccabi" – which often achieved large victories. Furthermore, as with Egypt's Jewish community, Sudan's Jews were interested in the arts, establishing a theatre where performances starred Jewish actors, as well as founding a cinema that was frequented by Sudanese citizens of all beliefs and faiths – namely the 'Cinema Coliseum', which screened foreign movies, and was established in 1935 by two Jews Lycos and Anton. The cinema used to show two films in the same program.

However, in 2015 the historical cinema was demolished, after being purchased by an investor who decided to replace it with another project.

The Sephardim: from Spain to Sudan

Sudanese researcher and journalist Seham Saleh writes in an article that the Jews who arrived in Sudan were from the 'Sephardim' Jewish ethnic division, who were descendants of Jews who once lived in Muslim Spain before being subject to persecution and ultimately expulsion after the fall of the last Muslim Kingdom on the Iberian peninsula of Granada in 1492, thus fleeing to North Africa, from which they made their way to the Sudan, where they would reside for a long time.

Saleh estimates the number of the Jewish community at the time to be approximately a thousand individuals, most of whom lived in Omdurman, while others would later depart to other cities such as Nuri, Merowe, Al Dabbah, Port Sudan and Wad Madani.

According to Saleh, Sudan's Jews benefited from the tolerance they found in the population to the 'other' at the time, with the society being a forgiving one far removed from religious extremism, adding that Jews established huge commercial projects and worked in the field of imports and exports – especially agricultural products and the leather trade, dominating these fields. Furthermore, the Jewish community established important companies in the fields of finance, construction, hospitality (hotels) and medicine, with Saleh revealing that amongst the most famous Jewish merchants at the time in Sudan being "the sons of Murad Israel", "Habib Cohen", "Leon Tamam and brothers", the "Siroris" brothers, "Viktor Shalom", "Al Abudi" and others.

Saleh adds in her article that Sudanese society was inclusive of Jews until the year 1948, when hostility started to emerge against them following the establishment of the State of Israel and later tripartite aggression against Egypt in 1956. It was during this period that Sudan's Jews began to flee, at their forefront the "Adas family" which went to Nigeria, before the majority of other Jewish families followed suit with migrations to Europe, the United States and Israel.

The Moroccan, the Baghdadi and the Istanbuli

Saleh affirms that Sudan's Jews succeeded in integrating into Sudanese society, excelling in commercial and social activities, but nonetheless notes that some were fearful of displaying their Jewish faith and origins – noting that the majority gave themselves Arabized names that did not express their Jewishness: notably al-Maghrabi ('the Moroccan'), al-Baghdadi ('of Baghdad') and al-Istanbuli ('of Istanbul') – names that Saleh explains indicated the original lands from which they arrived or in which their ancestors resided for a certain period of their lives.

Saleh also reveals that Sudan's Jews used to speak Arabic in the Sudanese or Egyptian dialect, and were also proficient in English and some other languages, such as French and Spanish.

Some Jewish families, Saleh also notes, insisted on remaining in Sudan – with time converting to Islam and marrying their sons to Sudanese Muslim women; others however remained devoted to their Jewish faith, such as the members of the "Al-Dawik" family that worked in the trade of fabrics and textiles.

Ultimately, Saleh believes that the main underlying reason for the Jewish fear of remaining in Sudan during this later period was the decision of Colonel Gaafar Nimiery to nationalize and extensively confiscate the properties of Jews. Years later, specifically in 1987, the Jewish temple in Khartoum was demolished, and its land sold to a Sudanese bank.

The Jews of Sudan departed and the only remnants they left behind were the graveyards in the center of the commercial district of the Arab market in Khartoum – which remains a desolate land to this day, with many Sudanese not even aware that there lie the graves of their ancestors.

While awaiting the reactions of Sudanese-origin Jews to the call of Minister Mafrah, some voices of Sudanese-origin Jews have already begun to comment on his invitation. Accordingly, the BBC conducted an interview on the 9th of September with Dizi Aboudi, a daughter of a family of Sudanese Jews and the founder of the site "Stories of Sudan's Jews" – in which she expressed her belief that Khartoum's call for the return of Jews was a very positive invitation which was met by much happiness amongst the Sudanese Jewish community, while adding that the minister's invitation can lead to the improvement of relations between Sudan and Israel in the future.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!