"Israel is not my homeland. Israel’s government has, especially of late, tried to speak for international Jews, and I reject that. Israel does not speak for me.” So says Arab-American author of Jewish faith Massoud Hayoun, in conversation with Raseef22. “Before 1948, my family and my communities made pilgrimages to Jewish holy sites in Palestine. There are also Jewish holy sites in our own countries that are very important to our religious practice. Until Palestinian lives and dignity are internationally recognized and legally guaranteed, I must refrain from making the same pilgrimages as my ancestors.”

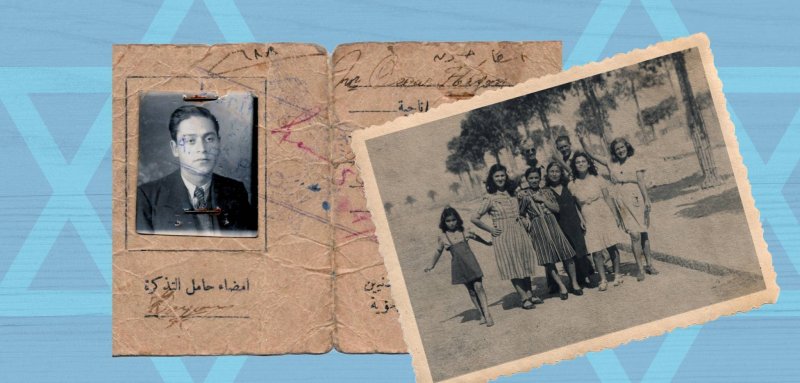

Hayoun recently published a book on his identity and its political implications entitled When We Were Arabs. In the book, he narrates his family history: the stories of his Jewish Moroccan-Egyptian grandfather Oscar, his Jewish Tunisian grandmother Daida, and the repercussions of the tumultuous 20th century, which forced their families to migrate separately to Paris, where Oscar and Daida met. Oscar and Daida would then move once again to Los Angeles, where Hayoun was born. The book uses their story to establish a political theory that acts as powerful roadmap for our times.

“The book isn’t only for my family or other Jewish Arabs,” Hayoun says. “The book is for all Arabs and all humans. The book should be taken a ‘fuck you’ to the anti-human tendencies we are seeing internationally, in the endless assault on Palestinian lives and in the intense fascism of the West.”

The book isn’t only for my family or other Jewish Arabs. The book should be taken as a ‘f*ck you’ to the anti-human tendencies we are seeing internationally, in the endless fascist assault on Palestinian lives.

Massoud Hayoun on his Jewish Arab grandmother: “Wherever I find Arab women who refuse patriarchy, imperialism, and so many other forms of oppression and degradation, I find Daida, still alive. Long after her death, Daida has become human indignation.

Massoud Hayoun: Although my parents are gone and I live alone, my family is actually quite large, when you count all the Arabs who choose that identity, from Marrakech to Manama.

Hayoun describes the book as "an unconventional, decolonial memoir of my grandparents and the worlds that died in large part with them. It is also a work of political theory and a call to experience solidarity across historical boundaries in these exceptionally dark times.”

The book seeks to deconstruct the effects of colonialism on his family, pointing to events and policy documents from colonial-era North Africa. “I look at the ways in which we were Arab, the ways in which we were colonized by Europe, and the ramifications of that colonialism,” he says. “You go a step further, and this book is about the Arab identity. It is about the complexity, the diversity, and the beauty of what Arabness could become (and is already becoming, if we choose it) in our modern times — the Arabness I describe is likely very different from the Arabness that exists in the minds of many other people, Arab and non-Arab. You go a step further, and the book is a work of political theory, very broad in scope. One man, an intellectual in Britain whom I consider a brother, read it and told me it is about human nature: We can have 1,000 things in common and focus on the one difference and learn to hate each other.”

On the research that he undertook to write the book, Hayoun says: "The resources used in the book are available all over the world. I didn’t have the resources to travel abroad for the book, so I’d say I was pretty frustrated at times to not be in Tunisia or Egypt or the West Bank at the Darwish Museum.”

“I consulted records and spoke with international people in Europe, North Africa, and the United States,” he continues. “I think, when I started this project, I imagined that it would require a lot more travel to my family’s hometowns and to the national archives of Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, and elsewhere. In reality, it wasn’t that much of a physical adventure. More so, I found myself making special requests to different institutions, requesting rare books and documents from UCLA and other Los Angeles-area libraries and universities, and speaking to international experts over Skype.”

Hayoun points out that he has since made many friends and new acquaintances during the writing of his book, as well as getting acquainted with many Arab women all over the world. On this, he says: “Where I find Arab women who refuse patriarchy, imperialism, and so many other forms of oppression and degradation, I find Daida, still alive. Long after her death, Daida has become human indignation. So she is everywhere, and she won’t rest until the world is much better.”

My Large Arab Family

Hayoun was raised by his grandparents and his grandmother became "a very close friend and intellectual colleague," he says. “For a long time, we worked together on the details of this project. Three months after we got the book contract from my publisher, she died.”

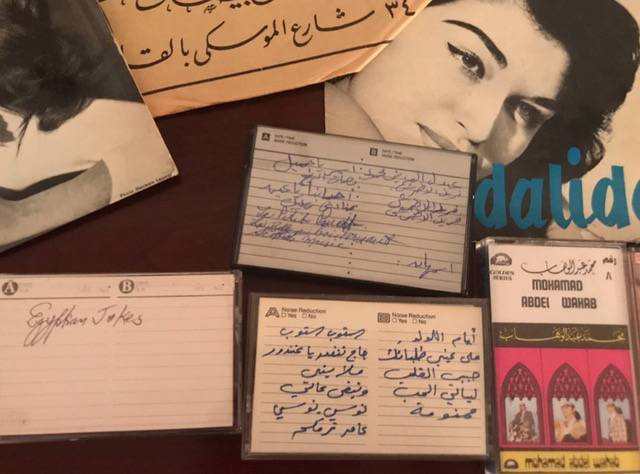

It was then that Hayoun realized that many of the intricate details of his grandparents' identities and words had faded with their passing, “but at the same time, I realized more than before that their Arabness is what remained, what was transmitted to me, and what ties me to so many other people and places internationally, in which I recognize my family,” he says.

According to Hayoun, “My grandmother is my co-author, my best friend, and my intellectual partner in this project. Since her death in 2017, I have been in a state of near-constant mourning. Life has lost all flavor. I anticipated, when we got the contract, that I would feel joy when the book was published. I have not felt any joy, because I am incapable of joy, since she died, in the way that Fairouz no longer smiles publicly. In the worst moments of that mourning, I wonder which of us — me or her — is the ghost.”

Hayoun spends a lot of time in the kitchen, preparing Moroccan, Tunisian and Egyptian foods – some of which are specific to the Jewish communities in those countries; however, most of what he prepares are dishes enjoyed by most Arabs. Hayoun did not used to cook before his grandmother's death, and she never taught him to cook either. He explains: "But I used to sit in the kitchen to do my household chores, watching her as she cooked. When thinking about it, I realized that this was the same way that Daida learnt to cook from her mother Kamouna: by watching in silence."

He continues: “I enjoy making gigantic lunches for friends (I tweet pics of the food on my twitter). So I invite your readers to make friends with me, if only for all the couscous and koshary.”

Ultimately, Hayoun notes: “Although Daida and Oscar are gone and I live alone, my family is actually quite large, when you count all the Arabs who choose that identity, from Marrakech to Manama.”

When asked whether he has any plans to publish his book in one of his original homelands – Egypt, Tunisia or Morocco – Hayoun expressed his interest and happiness to do so: "I would love to. But for that to happen, an Arabic-language publisher would need to buy the rights from my American publisher, The New Press. I love any excuse to be in any Arab country. When I go back to an Arab country, I return to the West afresh, with the feeling that I have a home and a family and that I belong in this world."

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!