Every morning, Algerian photographer Emad Tabayba opens his eyes to a new and unfamiliar world: one in which former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s photos are replaced by new drawings and new colours. It is a world with cleaner streets and what he describes as a more relaxed demeanour in the populace.

Tabayba says that the young men of his neighbourhood in the eastern city of Sidi Mubarak share the financial costs, burdens and physical effort to clean and renovate their neighbourhood, part of a new “spirit of urgency” that he says has consumed Algerian society after toppling its dictator following a wave of protests earlier this year.

“In their pursuit of a new relationship with the public sphere, that which they used to previously violate by littering, or by neglect in their expression of resentment towards the ruling regime supervising it, Algerians are now taking off or expunging everything that symbolised the former ruling authority, such as pictures of the president and slogans of the ruling party, replacing them with new images and drawings that express their ideas, dreams and aspirations,” he says.

Every morning, Algerian photographer Emad Tabayba opens his eyes to a new and unfamiliar world: one in which former president Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s photos are replaced by new drawings and new colours. It is a world with cleaner streets and what he describes as a more relaxed demeanour in the populace.

“In the past this same young guy used to be forced to stand everyday to salute the flag in educational institutions, because this was a government order,” Tabayba adds. “As for today, he has stormed the headquarters of the municipalities and government institutions and recovered that flag, as he now sees it as a symbol of a nation that he is the owner of, not the property of the regime.”

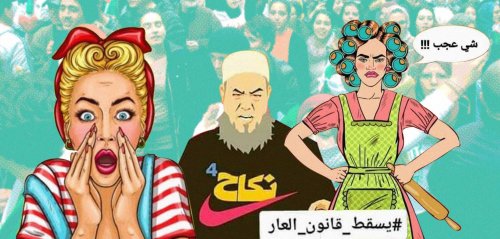

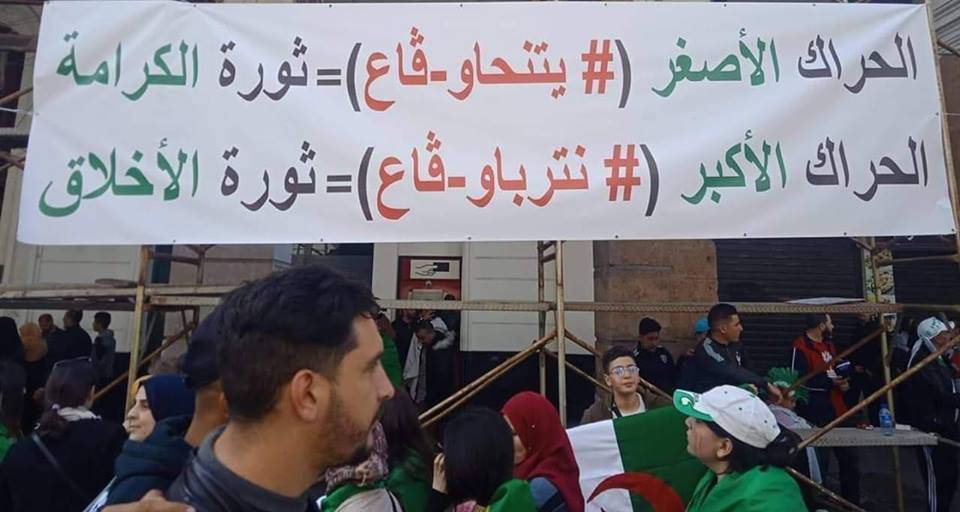

The public’s answering of the calls for social change made by civil society forces, starting on the third Friday of the protest movement which took down Bouteflika, now enjoys a broader acceptance within society. Here, the political slogan “Yetnaho Qaa’” – meaning “Let them all step down” – has been increasingly raised, while others have adopted the slogan “Netrabo Qaa’” meaning “Let us all have a [new] upbringing” – in what are two parallel scenes that define the current stage: calling for political change, and social reforms meant to consolidate social cohesion and improve the public sphere.

Philosophy professor Bechir Rabouh described the worst aspect of Bouteflika’s reign as the burying of the collective psyche and spirit of Algerians, forcing the abandonment of any social cause or attempt at building civil society.

“Whenever I asked anyone, ‘How are you doing?’, they would answer by saying ‘Nothing to hope for".

“Whenever I asked anyone, ‘How are you doing?’, they would answer by saying ‘Nothing to hope for,’” Rabouh says, a condition that he describes as a form of nihilism more destructive to society than occupation and terrorism, because it gives birth to a state of reclusion and heightened distrust of one’s environment.

This helps explain the spread of illegal migration amongst Algerian youth, which has reached the extent where some declare that they would, in Rabouh’s words, “prefer to be eaten by a whale in the sea, in the event that he boards a migration boat, than to be eaten by worms in the grave, if he stayed in Algeria.”

But Rabouh says this attitude has changed after Bouteflika’s ouster.

“As soon as the popular movement took off three months ago, the relevant authorities confirmed the decrease in the number of illegal migrants,” he says. |Indeed, some of the young men who were able to previously migrate have returned to Algeria, in order to share in the dream of a new Algeria with their fellow citizens.”

The Algerian government has long refrained from revealing the true number of migrants leaving Algeria, even though it does acknowledge the existence of the phenomenon. A few weeks before his resignation, Bouteflika’s government allocated a day for studying the causes of the migration and the solutions which can limit it. Algeria also hosted the international symposium on illegal migration in August 2018, having been asked to do so by the parliament of the African Union (AU).

According to a 2017 report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Algeria ranked fifth in the list of countries with the most number of refugees fleeing to Europe, after Syria, Morocco, Nigeria and Iraq.

Meanwhile, a statement by the Algerian Ministry of Defence on March 30 disclosed a decrease in illegal migration attempts from the shores of Algeria to Europe, with only 120 such attempts taking place during the protest movement, compared to “record numbers” in previous periods.

“Happiness Committees”

About 200 km east of the capital Algiers lies the city of Bordj Bou Arréridj, where a group of activists launched an initiative named “Happiness Committees in Residential Neighbourhoods” – following the example of the Happiness Committees in the United Arab Emirates – which aim to restore social cohesion and intimacy amongst the residents of a single neighbourhood, in the form of a collective solidarity tasked with fixing the area’s problems.

Mohammed Hanashi, one of the activists engaged in the initiative, said that Algeria’s residential neighbourhoods have come to resemble “graveyards” more so than human, social and cultural spaces.

This can be seen in the fact that most of the neighborhoods are given a number rather than a name, with the number denoting the sum of its units: so for example there is the ‘450 residences neighbourhood’ and the ‘1000 residences neighbourhood,’ Hanashi says, describing it as “an attempt to bury any taste in public life, whereby a neighbour doesn’t know anything of their neighbour, and does not interact with him except on the staircase of the apartment.”

Proposals by this ambitious initiative form the basis of debates on how best to achieve the Happiness Committees’ goals, which are many: cleaning and decorating the neighbourhood and planting trees, supervising security, dispatching sports, cultural and artistic delegations, fostering and sponsoring skills and talent, organising tourist, leisure and educational trips, holding classes to increase literacy, devising special programmes for the elderly and the retired, finishing the construction of a kindergarten for children, fixing neighbourhood facilities, increasing and maintaining street lighting, twinning programmes with other neighbourhoods in other cities, and improving rubbish-disposal.

This civilian initiative – which has adopted the motto “Citizenship, Humanity, Solidarity” – also works on spreading the culture of reading amongst residents, planting small libraries inside homes, cafés and the neighbourhood squares – while also working to revive the culture of visitations between neighbours, as is the customary practice of villagers. Other goals include taking care of the land once again, cultivating the culture of initiative-taking amongst residents, and escaping the mentality of waiting for everything to be provided by government institutions, and instead opening up to the role of private institutions in sponsoring certain initiatives that require funding.

The initiative also proposes coordinating with the Imam of the local mosque in order to ensure that weekly Friday sermons are in harmony with the pressing social need to adopt certain reforms in thought and behaviour. Initiatives offering real social utility are also proposed to the mosque committee: notably including funding the mosque from the Zakat (compulsory alms) fund, with such an effort taking place in parallel to efforts to reinforce coordination with the administrations of local schools and colleges in order to launch a rebirth of cultural and educational initiatives; and, finally, adopting ‘dialogue circles’ between families, teachers and students.

In short, the initiative seeks to exercise what the state used to perform socially and has long since neglected in favour for its own political interests – thus redirecting it to serving the people themselves, improving their social interaction and engagement, cohesion and solidarity, and their feeling of belonging.

Fears of division and the return of the regime

After the 16th protest Friday of the anti-Bouteflika movement, the poet Rachid Belmounne shared a post on his Facebook page saying: “I have started to fear for my country.”

I called him to try and find out what the reasons for this fear were – receiving the answer that the popular movement was no longer as unified as it was when it began.

“The struggle was between the people and the ruling gang,” Belmounne says, “It was able to destabilise its [the regime’s] junctures and give us the feeling of being able to change, but as for now, the struggle has begun between one segment of the people and another, in terms of supporting or opposing the proposals of the military establishment, which has refused a solution outside the constitution.”

I asked Belmounne if he considered the social initiatives that have grown out of the protest movement to be the source of any hope. He responded by expressing his fear of what he called a “political setback” within the protest movement.

“Were the Algerian youth going to engage themselves in initiatives and projects with public benefit if not for the first five Fridays that gave them a feeling of being able to achieve political change?” he says. “I fear that this new feeling will lead them to disappointment, in the midst of the civil and military authorities reassembling themselves, so that they relinquish the spirit of taking the initiative, and program themselves once again onto the dream of migration.”

He adds: “The intransigence of the ruling faces in dealing with the demands of the movement are not only due to wanting to remain in power, but also to break the new determination of the Algerian street, because this is the terrain on which change takes place.”

Meanwhile, in the city of Setif in eastern Algeria, my attention was drawn to a grouping of male youths who were decorating the walls with drawings of natural scenery, masses of people carrying the national flag, and faces of revolutionary figures including Che Guevara and Larbi Ben M'hidi – one of the most prominent martyrs of the national liberation revolution against the French colonial authorities.

Yet a certain tenseness seemed to dominate their words and movements, leading me to probingly ask what was going on. Here, I would discover that one of the members of the group refused to pay his share of the decoration costs as had been previously agreed. His justification? That he had lost the desire to stay in Algeria.

I asked him what the reason for his change in attitude was, and he responded by saying that his initial engagement in decorating his neighbourhood stemmed out of his feeling that the corrupt regime was on its way out.

Now, however, he was “assured that it will remain stronger than it was, as long as half the population is opposed to the other half, defending the same corrupt regime.”

At this point, he was asked by another member of the group: “Are we asked to decorate and clean our place of residence for us or for the regime?” But the young man responded: “I have lost trust in everything.”

The Algerian popular movement now stands at a crossroads, with the desire of the popular parties that helped overthrow Bouteflika to exclude the military establishment from having a role in the transitional period (as well as to ostracise former symbols of the regime) clashing with that of the ruling interim authorities.

In the face of such demands, Algeria’s temporary president Abdelkader Bensalah insisted last Thursday that the country’s current situation necessitated his remaining in place.

In the end, regardless of what the terminus of the Algerian popular movement will be, there has been a new spirit that has noticeably reanimated Algerians – and herein lies the question: can this spirit result in political parties or civil organisations that can have an effective political role, or is Algeria doomed to the fate of the countries that preceded it – the extinguishing of that spirit, and the transformation of the ‘Spring’ into a tyrannical ‘Winter’ once again?

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!