Amirah Qureshi was at her university in Algiers when the first protests that would later morph into a revolution broke out against former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, and his bid for a fifth consecutive term in office.

Ever since her early youth, the 20-year-old Qureshi had been distinguished by a palpable passion for politics, which would not only drive her to join the marches but to also push her fellow female colleagues at the Faculty of Media and Communications to do the same– urging them to participate in the procession heading towards the presidential palace.

As they tried to leave the campus, however, they were met with the closed gates of their university, ordered shut by security personnel in the vain belief that it would stop the invigorated youth, the oldest of whom was 22, from getting involved. But the students started to scale the gates, with Qureshi and her friends in tow, eventually forcing university security to reopen them.

The students proceeded to gather outside of the university building before beginning a march towards the presidential palace. When they were 400 metres away, security forces fired tear gas to disperse the students, who headed towards Didouche Mourad Street in the centre of the capital to join the rest of the demonstrators.

Meanwhile, 425 kilometres south-east of Algiers, 18-year old Kawthar Uthmani was waiting for the end of Friday prayers in the province of Batna to join the first revolutionaries of post-independence Algeria streaming out of the mosques. However, unlike her counterparts in the capital she noticed the near-absence of women in her province’s protests, with Uthmani almost the only woman in the square.

It was, she said, a form of ‘first-day’ apprehension, fueled by concerns that the marches would not be peaceful or would be met with violence by security forces. On the following Friday, Batna’s women joined in.

Young feminists

Despite their youth, both Kureshi and Uthmani were already involved in feminist groups on the ground and on social media platforms. Algeria’s political reality before the revolution did not allow for feminists to go to the streets too often to demand their rights. In the post-Bouteflika era, however, things have changed.

During the first week of protests, Qureshi met up with her friends to prepare and discuss the banners and slogans they would use, before agreeing to a date on which they would go to the streets and the route their march would take.

The following week, Qureshi proceeded to raise her group’s feminist slogans and demands, calling for the abolition of the country’s Family Law and equality between the sexes in both rights and duties. However, the banners and slogans did not appeal to some of the male youth in the protest, who proceeded to tear them and attack the girls.

Among the most important feminist demands are the abrogation of Article 46 of the Family Law forbidding adoption; Article 11 requiring a woman to be present with her guardian when signing a marriage contract; Article 7 allowing a judge to sanction the marriage of a girl under the age of 19, for reason of benefit or necessity; and Article 61 that stipulates that a divorced or widowed woman cannot leave the family home for the first three months after separation.

Because of their experience, the women proceeded to organise feminist-specific demonstrations, but were often harassed by their male counterparts, who believed their demand to abolish the Family Law untimely. This led Qureshi to ask: “If now is not the time, then when is?”

“Our demands do not conflict with the public demand, which is that that we want a free, democratic Algeria,” she told Raseef22. “But this demand cannot be accomplished without liberating the Algerian women, and so we call for the abolition of the Family Law, because it oppressed Algerian women and is reactionary.”

Uthmani called for freedom and gender equality, in addition to changing the Family Law to accommodate Algerian women of the present day.

“Amending this law is a human right before being a feminist one, because it oppresses the woman and her freedom in the name of religion and authority,” she said. “We should participate in formulating laws that can protect us in a patriarchal society, and that will not be fixed between day and night.”

March 8 protests

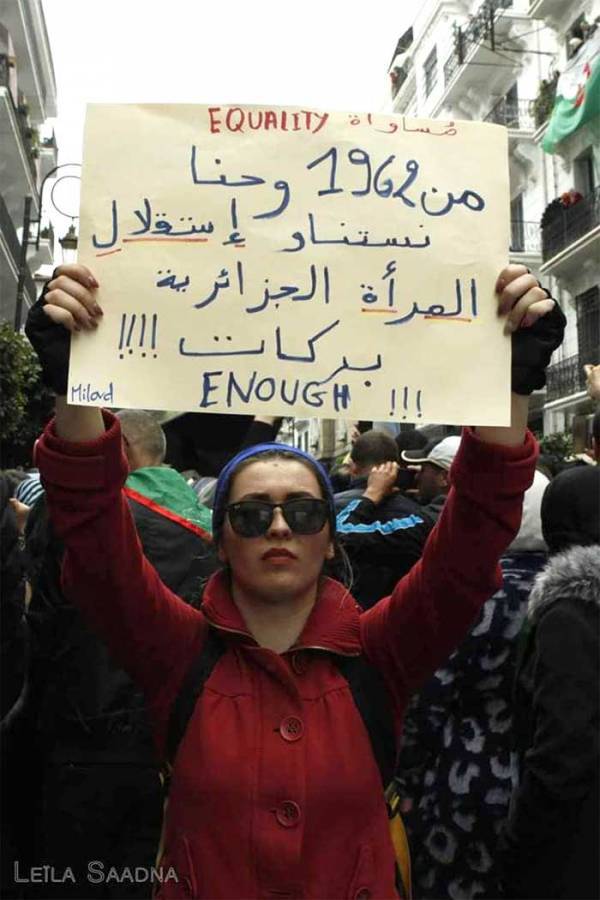

International Women’s Day on March 8 witnessed a very strong representation of women in the protests compared to the two preceding weeks. This led feminist activist Amal Hajaj and her feminist friends to focus their deliberations on what they wanted out of the popular movement, as women who lived in Algeria.

Hajaj subsequently convened, along with her friends, a feminist association in Algiers named Algerian Women Demanding Their Rights. An enlarged feminist collective composed of the different associations was subsequently established on the March 22, called Algerian Women For Change Towards Equality.

The new collective proceeded to release several statements condemning the regime and calling for their legitimate rights, encapsulated in the abolition of the Family Law and the enactment of civil laws which are fair to Algerian women, as well as translating their statements into four languages and sending them to the press.

Hajaj told Raseef22: “In addition to calling for a radical change in the regime and everything derived from it, we as feminists call for a democracy that encompasses our rights, for if we are partners in changing the regime, we have a right to decide what comes next.”

Hajaj added: “We have throughout history participated in revolutions for liberation, whether the uprising of October 1988, or the liberation of Algeria from Islamist terrorism during the black decade, but the prevailing patriarchy has betrayed the feminist strugglers and did not leave any room for them in political life after independence, and even the laws and Algerian customs and traditions did not do much justice to women, and so Algerian women should insist on their demands at this time and should not pay heed in any way or form to the phrase: ‘It’s not the right time.’”

Hajaj said that her movement’s demands are not solely confined to the full abolition of the Family Law, but also encompasses the enactment of laws that achieve justice and equality between all without exclusion or discrimination, in addition to laws that criminalise violence against women.

She called on Algerian feminists to work towards changing social conceptions which create a derogatory view of women, so that women across Algeria can determine their fate “without guardianship.”

Friday, March 29

Two other Algerian activists working in feminist circles since 2014 are Mellor and Hayat Mijbar, who previously administered the former Facebook page “Enough-DZ” (Enough Algeria) before it was taken down by the site due to being repeatedly reported by users, and which encouraged women to demand their rights.

The two women sought to take the struggle to the field, and agreed to meet in the last week of March with the feminists they knew to elucidate their demands. These included cancelling and amending twelve articles from the Family Law in the immediate future, followed by the abolition of the law altogether and its replacement with a new formulation that included the input of women after the end of the protests.

The current law was enacted on June 9, 1984, with the country then undergoing formidable economic challenges, and the presence of women in the political and social arena was much more diminished.

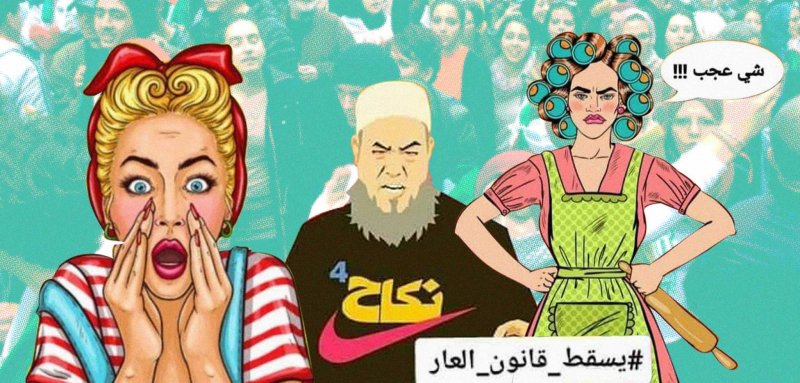

Mellor subsequently undertook the task of creating banners, often deploying the same slogans she had been using for years on her “Enough-DZ” page.

The young women proceeded to choose the morning of Friday, March 29, with the streets empty of protesters before Friday prayers, as the moment to go to the streets and put up their posters calling for the abolition of the Family Law, using the slogan “Down with the law of shame,” concentrating their activities in the capital Algiers and the city of Béjaïa 300 kilometres to the east.

Unlike the case in Algiers, however, the feminists were met by a different reaction in Béjaïa. The posters and stickers did not appeal to some of the protesting young men, such as one which portrayed a man and women on the verge of kissing while denouncing the legal article forbidding the marriage of a Muslim woman to a non-Muslim, as well as another flyer objecting to a legal article preventing a divorced mother from keeping her children. The protesters proceeded to beat up the women and tear the posters.

Mellor told Raseef22 that feminists in Algeria have been participating in the weekly Friday demonstrations against President Bouteflika since the start of the protests. Before the current movement, she said, they had been prevented from going to the streets as peaceful protest and assembly had been banned in Algiers since 2001. Nonetheless, she said that during this period feminists still attempted to organise several peaceful protests, only to be shut down by security forces.

Mellor recounted one such march taking place in August 2018, when the feminists attempted to organise a peaceful vigil and minute of silence commemorating the life of an eight-year old girl who had been kidnapped, raped and killed, only for police in central Algiers to ban the assembly and deal roughly with the protesters.

Mellor said: “We have been in the popular movement since the start on February 22, as well as many women and feminist figures who have participated in formulating it [the protests], since women have been struggling in the political arena over many long years, with some opposing the third and fourth presidential terms of Bouteflika. And so, the presence of women in general and feminists in particular in the political and popular movement in Algeria was not born yesterday.”

“We are Algerian citizens living in Algeria,” she added. “We care what happens in our homeland, for the course of these events will affect our lives and therefore we must affect it in turn.”

Feminist activists were part of the early protests, but felt that International Women’s Day demonstrations should have accorded greater importance to the situation of women in Algeria. Most feminists were subsequently subject to harassment, sexual and otherwise, and their banners were disparaged by many of their male counterparts.

Others called on them to put away the banners, arguing that the time was not right to call for women’s rights and that everyone should unite behind a single banner. Some feminist protesters were subjected to heavy beatings.

Ultimately even the prepared feminist chants were absent, with the voice of the crowd eclipsing that of the feminist activists, who were ultimately a minority compared to the thousands of men surrounding them.

Bouteflika’s resignation

After 20 years in power, Bouteflika tendered his resignation on the morning of April 3. Yet this hasn’t halted the ongoing demonstrations of the protesters, who have gone to the streets in record numbers on subsequent Fridays to demand the downfall of the “regime” in all of its symbols, and their exclusion from the transitional process.

Hajaj told Raseef22: “We did not go out in a revolution only against Bouteflika, for everyone knows that he has been inactive for years, but we went to the streets to uproot the regime along with all of its components.”

Meanwhile, feminist activist Mellor said that the feminists’ struggle was not only against Bouteflika, but against the prevailing patriarchal mentality in Algerian society. This meant that the struggle of the Algerian people writ large may be easier and shorter than the feminist struggle, which she said will not stop until all its demands are met.

Ultimately, the demands of Algerian feminists are many, Mellor said, elaborating: “We cannot specify our priorities accurately because [in] a country which has more than 20 million women with different backgrounds, cultures, patterns of living and mentalities, it is very difficult for its women to have the same demands.”

Nonetheless, she concluded: “Feminists north, south, east and west and from all age groups agree on one necessity that should be treated in the closest possible time, and that is the current Algerian Family Law which is unjust to Algerian women, both those living in Algeria and those abroad, and those married to Algerian citizens.”

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!