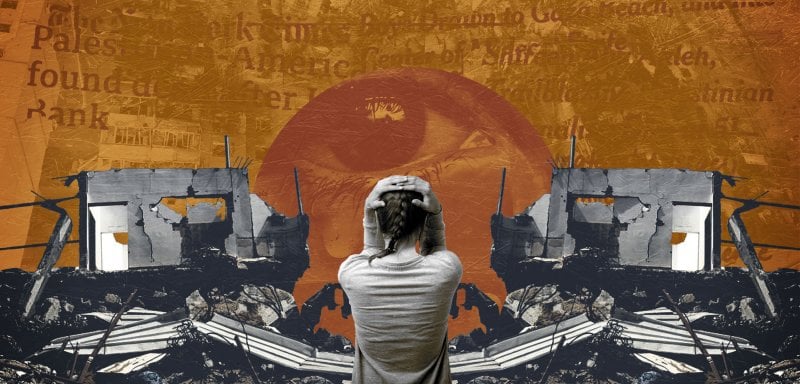

I try desperately to cry, but the tears won’t come. I turn to writing about the repeated loss of place, hoping it might offer a way to release the emotions stuck inside me.

During Israel’s last war on Lebanon, I lost my home in Dahieh, the southern suburbs of Beirut. I felt an urgent need to find a new house for my family, and I began a grueling search through the areas surrounding the capital, hoping I wouldn’t have to go too far from the city where I work, where I live, and where I spent my time with friends.

Since we moved to Beirut 26 years ago, we have never known stability. I continue to live in my imagination — somewhere between consciousness and dreams — within the walls of the homes I once lived and played in before Israel uprooted me from them or destroyed them completely.

I found myself trapped in a maze of searching for shelter during one of the most difficult times Lebanon had ever faced—when the demand for housing was so high that finding a place to live became a luxury, no matter the space’s condition.

After a month of searching, I found a new house for my family, the ninth in our series of homes in Beirut. Since we moved to this city 26 years ago, we have never known stability. We’ve moved from one home to another, as if trying to anchor our roots in a land that never stops trembling.

As for me, despite all the constant moving, I continue to live in my imagination — somewhere between consciousness and dreams — within the walls of the homes I once lived in, played in, and roamed through before Israel uprooted me from them or destroyed them completely.

My home disappeared beneath the rubble

A missile struck the building I lived in, in Dahieh’s Mrayjeh neighborhood. Our apartment, on the top floor, collapsed and disappeared beneath the rubble. In my imagination, I had thought if our home was bombed, the top floor would fall and gently settle on the ground, allowing me to enter through the balcony to retrieve my things. But reality was much harsher.

Concrete piled up on top of more concrete, and entire floors were reduced to rubble, while the belongings of our neighbors were scattered outside. Here lays a pot on the side, with children's clothes strewn across the debris; over there, the remnants of a couch, and a single orange high-heeled shoe.

The neighborhood cats were still roaming amid the rubble, as if they had found a new home in the ruins. Within this destruction, I spotted Afoufeh, my favorite cat. As if nothing had changed. She stood there, waiting for me as she always did, approaching with confident steps, demanding her usual share of petting.

To reach my home amid the rubble, I had to examine the site carefully, search painstakingly, and climb over the debris in hopes of finding a spot or vantage point from which I could glimpse our apartment. After several attempts, I found a way through a room on the ground floor of the neighboring building. Although that building hadn’t collapsed, it was devastatingly damaged, and the destruction of our building had left a gaping hole in its wall.

Through the gap, I stood facing what remained of our living room.

At the entrance to the destroyed building, the neighborhood cats were still roaming amid the rubble, as if they had found a new home in the ruins. Within this destruction, I spotted Afoufeh, my favorite cat. As if nothing had changed. She stood there, waiting for me as she always did, approaching with confident steps, demanding her usual share of petting. Spoiling her had been a constant part of my daily routine.

I still wander through my home in my imagination. I close my eyes and enter the house through its main door. I walk through the rooms as if everything is still in its place. In my mind, the house is clean, my room carefully arranged, and the mirror I hung on the wall is still waiting for me to strip off its brown paint and repaint it white. The living room is tidy, and the cane bookshelf adds a touch of beauty to the space — it’s one of the corners of the house I’m most proud of.

I keep thinking of the small things that made our house a home: a brass copper piece I bought from the Sunday market, the shelf carrying books I never got to read, our little vases, and several crochet pieces I had collected from various second-hand shops in the South, Tripoli, Hay el-Sellom, and Chiyah.

These seemingly marginal things made up my world. When I lost them, a part of me disappeared along with them.

From one room to the next

I close my eyes and enter the house through its main door. I wander through the rooms as if everything is still in its place. In my mind, the house is tidy, my room carefully arranged, and the mirror I hung on the wall is still waiting for me to strip off its brown paint and repaint it white. The living room is clean and orderly, and the cane bookshelf adds a touch of beauty to the space — it’s one of the corners of the house I’m most proud of.

I had always dreamed of our home being bright, free of the dark furniture that weighed heavily on my heart. I used to watch my father’s constant attempts to improve the space. Whenever circumstances allowed, he would buy random and mismatched pieces of furniture. But when it was my turn to decide, I chose light colors: blue couches, white curtains, accessories in red and green, and colorful antique vases. My choices were a clear rebellion against the dark brown that dominated our home’s furnishings — a color I could never stand.

I keep thinking of the small things that made our house a home: a brass copper piece I bought from the Sunday market, the shelf carrying books I never got to read, our little vases, and several crochet pieces I had collected from various second-hand shops in the South, Tripoli, Hay el-Sellom, and Chiyah. These seemingly marginal things made up my world. When I lost them, a part of me disappeared along with them.

I still wander through my home in my imagination. I step out onto the spacious salon balcony, where my mother’s plants once thrived: basil, aloe vera, and the miniature coleus plant. Beside them are pots filled with dry soil — remnants of a failed gardening project of mardakoush (marjoram), some flowers, and a few succulents. During our last visit, before our house was bombed, my mother had rushed to water the plants before we left. We hadn't been there for more than ten minutes; we'd come to gather a few necessities, unaware it would be our final glimpse of the place.

That day, my mother brought along whatever pantry goods she had prepared with her own hands, like zaatar (thyme) and kishk, while I rushed into my room and grabbed whatever clothes my hands fell upon in those frantic moments when my hands decided what to take, and I had no awareness of what I was leaving behind. I opened my closet, pulled out a large sheet, spread it on the floor, piled the clothes on top, tied it up, then ran down the stairs from the sixth floor.

The price of being uprooted from that place was steep for our family. In the late 1990s, my mother could no longer bear life under Israeli occupation, especially after the Lahad militia prevented my father from returning to Houla. The only option left for us was leaving.

That day, my mother had to leave behind the bag of dried local zaatar and the bag of sumac, realizing there would be no suitable place to grind and dry them as she was used to doing at home. The living room in our home would turn into a space for drying pantry goods, as our mothers usually do. My mother would spread sheets on the floor and lay out molokhia, zaatar, and sumac pods to dry.

That house doesn’t appear in my dreams anymore; as if my subconscious has already developed the coping mechanisms needed to deal with this loss.

A visit to my lost homes

In my dreams, my mind draws images of my village, Houla. It recalls the cypress trees and my grandmother’s house, which was demolished after the July 2006 War due to irreversible damage from Israeli shelling. A missile struck it and destroyed part of it, but instead of compensation going toward repairing it, the decision was made to tear it down, since restoring an old house built with rough stone and traditional craftsmanship would have otherwise cost a fortune. Building a new home was the less costly option. My grandmother built a new house, but this war destroyed that one, too.

In my dreams, I return to the house of my childhood — the home my grandfather built in 1942. It witnessed one of the most horrific Israeli massacres in 1948, when Haganah gangs killed dozens of our young men inside it and demolished two other houses on top of dozens of villagers. We lived in that house for years, and as I grew older, the more attached to it I became, as if a part of me remained trapped within its walls.

Even though more than 26 years have passed since we moved to Beirut, my mother still feels like a stranger living in exile, and I still live in the village in my dreams: playing in our home, chasing butterflies, crossing fields on my way to school, clinging to my mother’s dress as she takes me to buy a bucket of fresh milk.

In my dreams, I go back to this home over and over again, as if searching for something I had lost there. My mother, however, felt differently; she could never get past what she called the “haunting sense of desolation” that lingered in it.

I asked her many times why she decided to leave. One day, she responded.

“The thought of living in a house that witnessed a massacre never left me.”

The price of being uprooted from our homes has steeped itself into our family. In the late 1990s, my mother could no longer bear life under Israeli occupation, especially after the Lahad militia prevented my father from returning to Houla. The only option left for us was leaving.

We moved to Beirut, into a modest two-bedroom apartment in Hay el-Sellom, even though we were a family of nine. Ever since, we’ve known no stability, moving from one home to another between the neighborhoods of Hay el-Sellom, Tahwitat al-Ghadir, and Mrayjeh — as if trying to rebuild a small homeland in the heart of forced exile. And although over 26 years have passed since we moved to Beirut, my mother still feels like a stranger in the city, and I still live in the village in my dreams: playing in our home, chasing butterflies, crossing fields on my way to school, clinging to my mother’s dress as she takes me to buy a bucket of fresh milk.

In my dreams, I return to the house of my childhood — the home my grandfather built in 1942. It witnessed one of the most horrific Israeli massacres in 1948, when Haganah gangs killed dozens of young men inside. We lived in that house for years, and the older I grew, the more attached I became to it, as if a part of me remains trapped within its walls. In my dreams, I go back to it over and over again, as if searching for something I lost there.

I’m afraid the fire will devour my memories

After the ceasefire was announced last November, I couldn’t wrap my head around the idea that this house, too, had been burned. After much hesitation, I finally decided to return to Houla.

I went to my childhood home and stood in front of it, looking at it from the outside, but I couldn’t bring myself to go in. I turned back before the image of it, charred and black, could be etched into my memory. I just want to hold on to the image of the house I knew as a child, untouched by the fire.

I don’t want the occupation to once again rob me of what remains of the homes I carry in my memory, nor do I want scenes and images of destruction to distort the house that still lives on, full of life, in my dreams.

* The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!