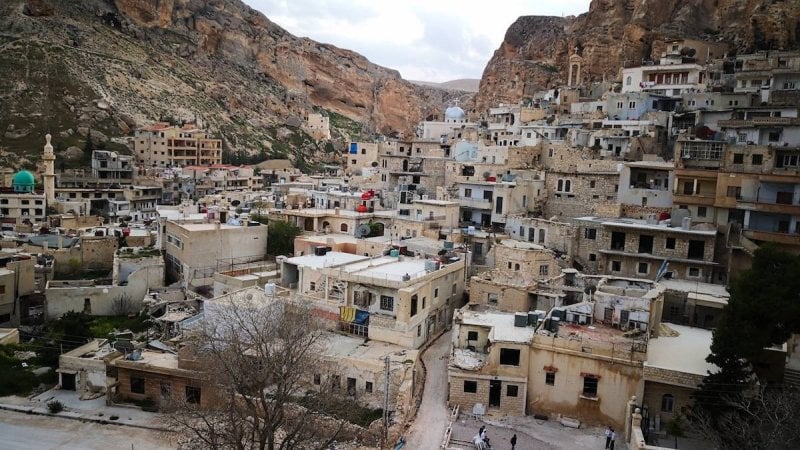

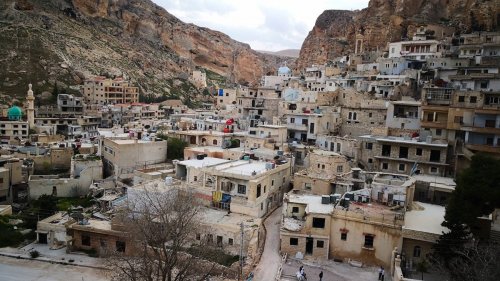

The church bells reverberate all around you; in the distance, the voice of children practicing the recitation of their religious rites. It’s six in the evening in Maaloula, a Christian town in the countryside of Damascus, and it’s time for the Good Friday prayer.

Hundreds of Maaloula’s residents rush to the two churches hosting the prayer services, exchanging greetings and anniversary wishes in their distinctive, colloquial Syrian accent interspersed with some words of Aramaic – one of the oldest surviving languages around the world, and still spoken in a number of Syrian regions to this very day.

In the Monastery of Saint Takla, which lies inside a rocky mountainous cavern on the outskirts of Maaloula, a number of mostly-elderly residents are assembled around some vocalists and nuns. A far larger number are assembled in the Monastery of Saint Elias in the middle of the mountainous town, coming from all over and encompassing men and women, young and old.

The prayers and exhortations of praise intertwine with the choirs and their hymns of the day – as on other Christian anniversaries mostly sung in Arabic but sometimes in Aramaic, a language that the people of Maaloula and some of its neighbouring towns insist on continuing to speak.

Aramaic is a Semitic language from the ancient dialects of the Levant, which prevailed as the official language in the region from the first millennium BC to approximately 700 AD, when it started to mesh with other languages in the region (notably Arabic). On a century-by-century basis, a gradual reduction in the number of proficient speakers occurred – eventually reaching a nadir of only 20,000 speakers today, according to estimates by UNESCO. The organisation now classifies Aramaic in the category of “Endangered Languages” – under threat of extinction.

“This is our language and the language of our parents and ancestors, but unfortunately it is no longer spoken as before,” says Abu George, a native of Maaloula, who is in his sixties. “In my generation and my father’s generation and his father before him, we used to go to school knowing only a little Arabic, but today the opposite is happening. Children go to school and can only speak a little Aramaic.”

Abu George points to a burnt section of his home, and a nearby broken window, as he laments the costs of the war that engulfed his country.

“Large parts of Maaloula were destroyed because of the war that passed through here about six years ago, when violent clashes broke out inside the town and at its outskirts,” he says. “More than half the population left and have not yet returned, especially the youth.”

“It does not appear that it will be easy to preserve our language today with everything we are going through,” he adds.

"In Damascus we speak Arabic but among each other we switch straight to Aramaic": Aramaic in Syrian Maaloula

"In my generation and my father’s generation and his father before him, we used to go to school knowing only a little Arabic, but today the opposite is happening": Abu George speaks to Raseef22 about language in Syrian Maaloula

One of the oldest languages still in circulation

Aramaic passed through several stages since its emergence to the present day, evolving from an informal and spoken dialect to a written and standardised one. Over the course of its progression, various forms of Aramaic would emerge, including Western Aramaic, Imperial Aramaic and Eastern Aramaic.

Eastern Aramaic can be further split into Syriac and Chaldean Syriac, Talmud Aramaic as well as Syrian-Palestinian Aramaic – the latter which prevailed as the lingua franca amongst the Jewish community during the era of Jesus Christ (while Hebrew was used in prayers and psalms).

In 600 BC, Aramaic would acquire its own alphabet after previously borrowing those of other languages for writing, allowing it to stand out and helping to facilitate its preservation. Furthermore, as well as serving as a conversational dialect, Aramaic would also be employed by various kingdoms and ruling regimes as their official, administrative and commercial language.

However, with the entry of Arabic into the region and its adoption by the inhabitants, Aramaic usage started to enter a period of gradual decline, eventually reverting to being a largely oral language, with the dwindling of the number of those versed in its written letters. It also declined in scope, with its spread retreating largely to a few geographical locations in Syria, Palestine and Iraq.

The generally-isolated geographical nature of these areas helped their inhabitants preserve its usage alongside their adoption of Arabic.

Indeed, colloquial Arabic dialects would also experience the borrowing of certain words from Aramaic that have no roots in classical (standard) Arabic. Thus in Syria for instance, the word “Shob” – meaning “free” – is derived from the Aramaic “Shoba”, while the commonly-used “bas” – “but” – is also sourced from Aramaic.

In particular, the different variants of Aramaic continue to be spoken in various regions of Syria today. Many inhabitants of the north-eastern Jazira region are versed in Syriac and Eastern Aramaic, while Western Aramaic, the variant commonly referred to simply as ‘Aramaic’, can be found in use amongst the natives of Maaloula, Jabadeen and Bakha’a (in the Qalamoun region in the countryside of Damascus).

Before the outbreak of the war, an estimated 30,000 inhabitants, Christians and Muslims, lived in the latter three towns; their population today has almost halved, following the repeated episodes of violence which plagued the region for several consecutive years.

Mary Haddad, a woman in her thirties who fled Maaloula in 2013 following the outbreak of violence in her town, said: “We have been speaking Aramaic ever since our youth, when we used to speak it at home with my father and mother. It was and remains the spoken language I use with my family and relatives in Maaloula.”

Her pride at preserving an important part of her heritage, as she describes it, is tangible. Haddad was displaced after 2013 to Damascus where she continues to live, visiting Maaloula regularly and insisting, despite considerable difficulties, to teach her son Aramaic.

“In Damascus we speak Arabic but among each other we switch straight to Aramaic, and we believe this to be part of our duty towards our language,” she says.

As with the rest of Maaloula’s inhabitants, Haddad only knows how to speak the language, but her love for it has prompted her to enrol in several writing courses in an Aramaic language institute that opened in Maaloula ten years ago.

But Haddad has arrived at the same disheartened conclusion as Abu George.

“It doesn’t appear that it will be easy to preserve the language today, especially after the displacement of the families and the town [language] institute shutting down its doors after the war,” she says.

Nevertheless, she simultaneously reaffirms her belief that the language’s cultural richness and vitality will see it through.

“Its links with all the details of our lives makes me certainly know that it is a language that will not die,” she says. “We have been imbued with it since our youth, we sing it in celebration and anniversary ceremonies and with the arrival of spring, and when we climb the mountains to practice the religious rites.”

“So how can we abandon it?” she adds, smiling.

No alternative but to preserve the language

In a house in Maaloula, George Zaarour, one of the few experts on the study of the language in Syria, can be found among his books and manuscripts. He spends his days reading and translating old Aramaic texts and even writes some Aramaic poems of his own.

He is also currently working on a comparative study of the different variants of what he terms the “holy” language spoken in Maaloula, Iraq, Palmyra and other places in the region.

Originally an Economics graduate, Zaarour explained the trajectory which led him to dedicate his life to the intensive study of Aramaic: “I worked a bit in the field of management but my realisation of the importance of the Aramaic language pushed me to devote my time to it and the study of its alphabet and its inscriptions throughout the stages of its development, since thirty years ago and until today.”

Zaarour, who is in his sixties adds: “I also teach it to those who are interested as well as academically to university students, in cooperation with Damascus University.”

In Zaarour’s view, Aramaic is far more than a simple language in isolation: he views it as inextricably tied to the land and is inherited successively from generation to generation.

“Whoever lives here and works the land is the only one able to preserve the vocabulary of the language,” he says. “Or shall I say, is the appointed incubator of the correct Aramaic in terms of its vocabulary and pronunciation.”

Unfortunately, Zaarour says “the numbers of those individuals are falling because of the displacement inside and outside of Syria, and the gradual disuse of the language.”

Ultimately, Zaarour warns that such a state of affairs carries the risk of the possible extinction of the language, thus necessitating the sounding of alarm bells to avoid such a fate.

“Half of those who are proficient in speaking Aramaic have passed the age of sixty,” he says. “Notwithstanding its importance, we should not suffice [only] with teaching Aramaic to the new generations, but should document the reserve [of knowledge] which is currently present, and strive to preserve and evolve the language and filter it from the Arabic terminologies that have entered it, and also to raise awareness amongst those who speak it of the importance of continuing to keep it alive and teaching it to children.”

The prayers eventually end and the families return home, yet certain Aramaic phrases still reverberate in the crowds. “Yen’at Alaikhon” – the Arabic equivalent of which is “Yena’ad Alaikom” (good wishes for the new year), “Aqbolsha Lokh Lishna” – “Al-Oqba Ly Kol Sana” (until next and every year) and “Meshikha Akam, Menjat Akam” – “Al-Maseeh Qam, Haqan Qam” (Christ has arisen, he truly has arisen), and the town finally goes to sleep to the well-wishes for peace, tranquillity and better days to come.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!