I think it’s true, even if I’m not the first to say it: it’s not enough to leave the geographical realm of a tyrant for his traces to vanish. That symbolic hegemony which for so long was exercised over our consciousness is deep below the surface, and almost feels natural. It is almost as if we constantly pronounce his name in a quiet voice without even realising.

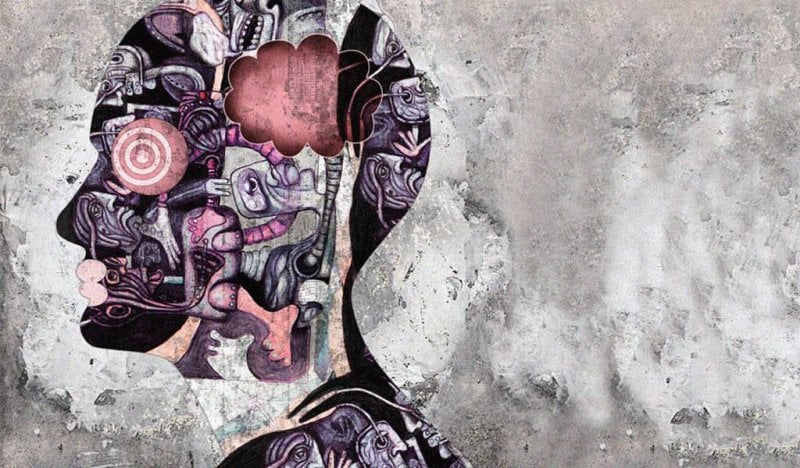

I think that the mental image I have of the world and how it works remains shaped by the tyrant, he who decreed acrobatic and illusory exercises against the “enemy”, and who taught us how to obey him in different contexts.

Even now, four years later in Paris and with restrictions over what I write or do having vanished, the ghost of the tyrant still follows in the wake of the ‘laws’ he decreed upon the world, threatening the ideas and frameworks that I work within and try to write about.

The first time I noticed this ghost was when I read something I had written a year earlier. I noticed how my explanations for some of the cultural phenomena I wrote about came from a single place, as if the symbolic configurations that I moved within all emanated from that one source, as if the entire world was prone to the same fundamental malfunction that had always been ignored.

And if, on the other hand, there was no principal flaw, then there was a mutating virus/tyrant, its symptoms differing from one victim to the other. In this world, these symptoms manifest themselves in different ways, and must always be observed and highlighted.

The same thing happened when I thought of the eternal and omnipresent tyrant – whether in symbolic or material form – in Syria and especially Damascus, where I once lived. Since I left the city, it has started to transform into a conceptual and often imagined morphology – one where everything was, I began to notice, the product of obedience and compliance.

To my mind, this was inseparable from the tyrant’s hegemony and his intentional and purposeful intervention in all of life’s details, whether the matter at hand happened to be a broken lamppost, or a massacre in some city.

This reference to the total power of the tyrant affected my understanding of the city. It is highly cohesive and tailored against its own population. My mental composition of Damascus started to transform everything within it to a set of calculated actions, ones that aim at achieving everlasting compliance with the tyrant’s will.

I faced the same issue in official transactions in France. Within me is this sort of paranoia, where all the decisions lie in the hands of one body which knows everything about me and records everything I do – as if it were personally invested in my daily routine, and where any recorded ‘mistake’ can be revisited later.

Of course, there is some truth in that, given the chilling effect that modern surveillance technologies have produced, and which obstruct the possibility of ‘disappearing’ (whether digitally or physically).

Nonetheless, there is this visualisation that I have of the domineering presence of the tyrant’s apparatuses and agencies. In fact, I’ve developed a theory that proclaims the existence of intelligence ties between Syria’s security apparatuses on the one hand, and France’s taxation, health insurance and internal affairs’ agencies on the other. After all, the detailed realities I experienced everyday in Syria are still taken into account here, and this has shaped my view of the law not as a humanitarian instrument, but as something directed against me: unforgiving, forged in a linguistic and material manner with the purpose of confronting me and throwing me onto the street.

The effects in this real world, which we were all deprived of in Syria, is reflected plainly in my daily life here. There is no seriousness when it comes to dealing with others. Many empty promises are made, and many fictitious appointments evaporate the moment my conversation with my counterpart ends. For as the tyrant never kept his promises, so too it seems have I developed the same propensity, particularly when it comes to those promises supposedly due in the long-term.

The effects in this real world, which we were all deprived of in Syria, is reflected plainly in my daily life here. There is no seriousness when it comes to dealing with others. Many empty promises are made, and many fictitious appointments evaporate the moment my conversation with my counterpart ends.

Everything that doesn’t have a current and immediate effect, I treat indifferently. My promises have come to resemble those of our parliament: its effects on the outside world evaporating the moment we finish announcing them. It is as if there is only one who can leave a trace, one who can change the world, one who can even take control of my own authority over myself, and do so at any moment.

Many of my relationships are in danger of dissipating and fading, for in case it hasn’t been evident enough or explicitly declared, I too defend my right to disappear: to be lost without a trace, like a fleeting tale.

I don’t know if the tyrant has a clear effect here, but the daily diet of performance and acting that I was trained on in Syria is still partially in force. It is as if ‘truth’ does not really exist, as if everything ‘visible’ now is at risk of fading away for no reason, much like the aftermath of an assassination or arbitrary arrest.

The deep corruption in Syria that seeps into our everyday lives is difficult to replicate in France – at least, not on the level of my personal transactions with authority and others. Still, there remains a form of distrust, especially at work. Here, a ghost moves in my head accusing everyone of shortcomings, of being unable to finish what’s required of them, because there must be someone corrupt among them, there must be someone not doing his job properly.

This mistrust in turn is reflected in my inability to work with a team; instead, I choose work where I alone can do all the tasks. Once I finish that work I lose my authority over it, and so this mistrust is mirrored in my ‘product,’ my written work. These themselves are again threatened with disappearance, and often end up incomplete (in my opinion at least) – something which can be noticed in some of the abruptly-ending sentences that I start and don’t finish.

Another observation: the coded language used in Syria, that stemming out of obedience and fear, gives everything said in my presence double meanings. Nothing that is said means what it means at face value.

More importantly, I have a firm belief that there is a permanent linguistic misunderstanding on the part of those who hear or read me. There is always some form of mix-up and thus a need to explain and clarify again what is said or written, even if is, in reality, patently clear.

This poor understanding I think stems from my upbringing, in which we were taught how to give our words multiple meanings. When those words, or noises, are written down, we discover the sheer sum of code and omitted content within them. It is almost as if there is a secret language, distinct from that ‘apparent’ and embellished one which keeps us out of trouble. It is necessary to comprehend these hidden linguistic blocs to explain how the world is analysed and realised.

The tyrant taught me to blame him for everything, to flog myself, to write long, nihilistic speeches about his deep effect. He removed my humanity from me, as if I was a product, controlled and pre-packaged. He forbade me to recognise my effect not only on the world – if it exists – but on myself too.

However, perhaps the tyrant taught me to blame him for everything, to flog myself, to write long, nihilistic speeches about his deep effect. He removed my humanity from me, as if I was a product, controlled and pre-packaged. He forbade me to recognise my effect not only on the world – if it exists – but on myself too.

But of course, it could be (and I jest) that the promises that I break and all this ‘nihilistic ordeal’ represent nothing more than a deep-seated cynicism, one which doesn’t even take the tyrant seriously, but only sees in him useful writing material.

A game, in other words, whose rules I pretend to be good at, so that I can fortify what I will write or have written before.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!