Headquartered at the front door of West House Hotel in Beirut’s Hamra Street, Maria answers the question of what had led her to this state with a smile: “I am not homeless, I am a nun answering my call. The Lord came to me asking me to perform my religious duties by roaming the streets and neighborhoods and spreading his teachings.”

Maria has always kept her face hidden behind her thick, curly hair. When she was still roaming the streets of Hamra and sleeping on its sidewalks, she would walk very slowly, repeating unintelligible phrases in a loud voice that would alarm any passers-by and make them avoid going anywhere near her.

Every homeless person has a story to tell, a story that recounts their suffering and what led them to the situation they are in now. In it, reality is often mixed with fantasy to involve contradictions that make it difficult to investigate the exact reasons that lead to the homeless state of each one of them, in a society that exaggerates the importance of family relations, and where belonging to the family, clan, and sect takes precedence over belonging to the state.

Solitude in the streets

Under Beirut’s Cola Bridge, right where the buses coming from the suburbs arrive, one can find the homeless scattered among a few fixed points, where they use “cardboard boxes” as mattresses and install their belongings near them. None of them would dare encroach on the space that the others have claimed for themselves, or else they will be considered trespassing. The boundaries there have been firmly drawn.

In 2019, Osama al-Ali, 36, moved to live under the Cola Bridge, after he lost everything he owned due to the economic crisis that befell Lebanon. He used to work in “painting furniture”, but “things have changed and the dollar skyrocketed,” Osama tells Raseef22.

Abu Ahmad (right) and Osama al-Ali (left), sitting under one of Beirut’s bridges

The thirty-something man details how he went from a craftsman to a homeless person practically overnight, “The never-ending power cuts kept interrupting and halting my work, and so when I ended up without any income, I decided to sell my house and move to Beirut to look for a job opportunity and make money, and since, I have been going from one failure to another.”

Osama is a father of three girls who live with their mother in her family’s home in the Ouzai region. In his opinion, “a man who is unable to provide for his family must leave so that he doesn’t become a burden on them”. He continues to look for a job with a good salary, but “the wages I was offered do not exceed three million Lebanese pounds (equivalent to 110 US dollars).” He further comments, “This amount is just about enough to cover the cost of the commute to work. In order to be able to return to my family, I must be more productive in order to secure a proper home for them.”

By his account, Osama would rather be homeless than appear weak and helpless in front of his family. He asserts that "my wife did not kick me out, I did that myself.” His inability to provide is not the only motivating factor for his decision, since his stay with his wife’s family isn’t acceptable from a religious point of view, “I cannot stay with them. In the house there are other women who I cannot live with,” meaning his wife’s sisters.

For his part, Abu Ahmad sleeps on a sidewalk in the Cola area, just a few meters away from the spot where Osama sleeps. In his story, it can also be seen how he would opt for homelessness over neglecting what is socially seen as a father’s duties.

Abu Ahmad, 66, refuses to live with his sons, “so that I will not be a burden” he tells Raseef22. He is a Syrian of Kurdish origin. He used to own a house in the city of Latakia in Syria, but today he refuses to return. He tells Raseef22, “I got all my children married, and I do not want to live far away from them. I visit them from time to time, but I keep my relationship with them formal.”

Abu Ahmad has been homeless for 15 years. At first he used to sleep in the Sabra area of Beirut. He looks back on that time and retells that, “there, everyone knew me and loved me”, without explaining what had prompted him to leave the streets of Sabra to the sidewalks of the Cola roundabout.

Samir, 54, is also living a story of homelessness that began in 2010, when he moved from Tripoli to Beirut. He says “At first, I used to sleep on the benches of the Ain Al Mraiseh Corniche at night, or would hide on the beach to escape being pursued by the municipal police.”

Samir uses a sidewalk in Beirut for a bed

Samir is a husband and father of two sons. He recounts that he used to live with his family in Kuwait in the past, and talks about “a Kuwaiti woman who framed me for the crime of drug trafficking by putting contrabands in my bag after I refused to get involved with her.”

According to his story, he was deported from Kuwait to Lebanon in 2008 after having spent a decade in Kuwaiti prisons. He adds, “When I arrived in Lebanon, I went to my brother’s house in Tripoli and stayed with him for a whole year, but his wife hated me, so I moved to live in the house of my younger brother, who never objected to my stay with him, except when my children stopped sending me money every month after I announced that I had converted to Christianity. That’s when he asked me to leave.”

At the time, Samir started a job cleaning the park at Horsh Beirut during the daytime, but he turned to begging for money after his health deteriorated. “Beggars are the richest people in Lebanon,” He explains, “I collect about 500 thousand Lebanese pounds per day, which I distribute upon the needy because Jesus has commanded us to do so.” Asked about state institutions, he says: “no one asks about me and only passers-by care about me,” he says.

Homelessness goes beyond the absence of adequate housing. It also means the loss of identity, emotional well-being, and physical and emotional safety, and this is a major social issue

About a year ago, Samir went from being “homeless at all hours of the day, to being homeless part-time,” as he put it. He goes from street to street during the day and then goes to the “Al-Saada Hotel”, which is a very simple hotel located at the beginning of Gemmayzeh Street. There, he rents a bed in one of their shared rooms for 50 thousand Lebanese pounds to spend the night in before leaving in the early hours of the morning.

He talks about a sharp decline in his mental state during the years he was imprisoned. On the other hand, he believes that his conversion to Christianity was the reason for “regaining my mind”. Accordingly, despite feeling lonely and despite his wish to have a “wife and daughter”, he refuses “to adhere to the condition that his family — his wife and children — placed so that he could go back to living with them, which is to return to Islam”. Hence, Samir chose to spend his days on the street. “This is the only way for me to connect with other people and maybe say hello to someone every once in a while,” he says.

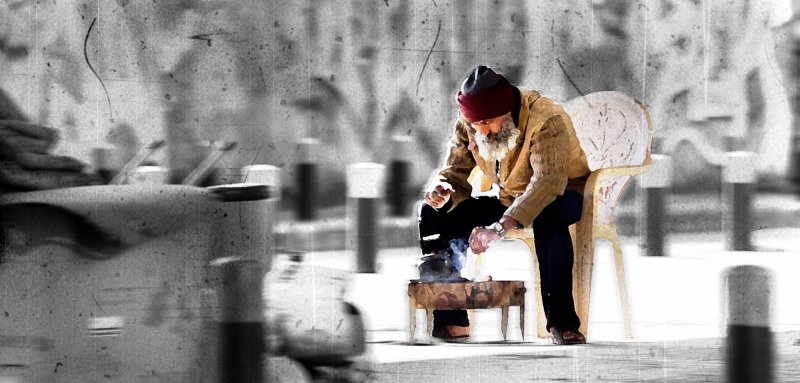

An elderly man begging in a street in Beirut

Abu Ahmad’s account, along with the stories of Osama and Samir, may have other aspects that haven’t been explored by this report, since it only details the accounts of homeless persons conditions, especially in terms of their families’ attitudes regarding their homeless state. However, the central question that remains is one regarding the role of the concerned authorities — whether they were official or non-governmental organizations — in dealing with the homeless conditions experienced by these people.

While Samir’s account of being afraid of sleeping on the benches of the Ain Al Mraiseh Corniche sheds some light on the approach that the Municipality of Beirut has made to combat homelessness, there is no known policy of treating homelessness as an issue that homeless people suffer from first and foremost.

Numbers on the rise

The director of the ‘Divine Providence Zgharta’ hospital (under the Couvent Mission De Vie Church in Adma), Mr. Boutros al-Rahi, indicates that the monastery aids the homeless and takes in the elderly who are at risk of becoming homeless. He says: “When a homeless person refuses to come to the shelter belonging to the hospital — and this is what usually happens — we secure his needs by providing him with food and medicine, giving him a specified amount of money, and visiting him on a regular basis.” As for those who go to the shelter, the director confirms that “We help them in every way in addition to providing them with mental treatment by professionals.”

“In the past, contracts were usually signed with the relevant ministries,” explains al-Rahi, “but at the present time, state assistance has stopped, and we now mostly depend on the donations that we receive.” In addition, the monastery “is in the process of communicating with the Ministry of Social Affairs with the aim of creating a new plan in light of the current situation.”

An elderly man sleeps on the street in Beirut

The monastery is currently assisting 250 people living outside, while the number of those residing in it is 37 elderly men and women, in addition to four beds that have been allocated for emergency cases.

Speaking on the increasing need for this service that’s provided by the monastery, al-Rahi says, “Before the economic collapse (2019), we used to receive about three calls per week, but today we receive four calls in just one day, and this is unfortunately beyond our actual capacities to help.”

Al-Rahi believes that the economic crisis, the COVID pandemic, and the migration of young people out of the country have left the elderly hanging in a weak link that exposes them to the risk of homelessness, especially women. He explains, “The number of women residing in the monastery is 23 out of the total 37. To this day, we do not know the main reason, perhaps because women become weaker socially over time and thus sadly get abandoned, and perhaps men are able to find a way to carry on with their lives.”

He explains, “We pick them off the street, where they have been exposed to physical and mental harm, and their mental illnesses have begun to appear, and here their trauma is treated and an attempt is made to reconnect them with their families.” He concludes with, “If we decide to provide 400 beds at the present time, I can say that this number will not be enough to receive and treat all the cases that come to us. We wish we could provide aid and assistance to everyone, but the (economic) collapse has imposed itself on us.”

Homelessness is not visible

Professor of Sociology at the Lebanese University, Layla Chamseddine, points out that homelessness is a growing phenomenon in all the countries of the world. She tells Raseef22, “The phenomenon of homelessness stems from many factors, and has no single definition for it, and this is the main problem. Homelessness goes beyond the absence of adequate housing. It also means a loss of identity, emotional well-being, and inner and outer physical safety, and this is a major social issue. And homelessness, if we want to define it in its broadest sense, is not only limited to the people who have lost their homes, but also to every person who is threatened with losing his/her place of residence whether for private or public reasons, or every person who does not have the financial capabilities to maintain his/her home.”

I moved to live in my younger brother’s house, who had welcomed me. When my children stopped sending money every month after I announced my conversion to Christianity, he asked me to leave

In Lebanon, Chamseddine attributes the increase in the numbers of the homeless to the exacerbation of “the factors that contribute to the spread of homelessness,” which are “poverty, unemployment, family fragmentation, a lack of services, displacement caused by war or conflict, disasters (for instance, the Beirut Port explosion in 2020), domestic violence, and addiction.” Together, these factors combine with “the lack of protection through social systems that must be provided by the state, most notably health care, social support, lowering unemployment rates, and policy-setting for the unemployed.” Consequently, “in the absence of reliable public policies, individuals are left in a weak position and become vulnerable to suffering — much more exponentially in the face of crises, doubling the likelihood of homelessness taking place, due to all of the aforementioned reasons.”

Between rent law and Beirut port explosion

Maya Saba Ayon, a legal researcher in Public Works Studio and the legal coordinator to the Housing Monitor (HM) project, explains that the Lebanese government does not guarantee the right to housing and does not implement the laws relating to it.

She tells Raseef22, “The conditions, standards, and controls are not in place, and there is a lack of criminalization of forced evictions, and no alternative solutions are provided to prevent people from being at risk of homelessness.” She adds, “The state of Lebanon does not play any role in regulating the housing sector, and it has handed this role over to real estate owners who make contracts and breach them whenever they want.”

She continues, “According to a report issued by the Housing Monitor (HM) on the last ten months, 180 cases of threats of forced eviction were recorded, 78% of which were accompanied by abusive practices by the owner that came in the form of physical or verbal aggression along with cutting off water and electricity from the apartment in order to have it evicted. “The main reason for these threats was the cost of rent, which has risen to more than two-thirds of the minimum wage, and which tenants can no longer pay.”

The problem of housing in Lebanon, according to Maya, is that “the Lebanese state intervenes, but without a comprehensive plan or a clear policy for housing. Rather, its intervention comes based on a response resulting from disasters and crises — that is, with the aim of patching up the aftermath.” In her view, what is worse are the changes that took place in the concept of housing itself during the past years due to the rental laws in particular, “The concept of housing changed from being an urgent social service, to a commodity subject to market fluctuations, and the first crisis began when the state liberated rent agreements in 1992, leaving any pre-requirements and conditions in the hands of citizens without any standards or controls that guarantee the rights of the tenant and the landlord, which thus has placed landlords and tenants in a cycle of permanent conflict.”

As for after the explosion of the port of Beirut, Maya says that “many of the tenants lost their homes, either because of the restoration process undertaken by non-governmental organizations that needed a long time to finish the work and could not match the urgent need of the tenants to repair their homes, or because the owners of the property refused to let the tenants return after completing the repairs with the aim of renting their houses at high prices.” The Housing Monitor had received 127 reports following the Beirut port explosion, and accordingly, “we prepared a report where we revealed that about 500 people were being threatened in one way or another with eviction and the loss of their residence,” explains Maya. Also, it was found that “about 29% complained of severe damage to the house after the explosion, 42% of them were threatened with eviction, and 21% were subjected to forced eviction.”

Although Law 194 issued after the port explosion on post-disaster recovery and the protection of affected areas and their residents from real estate speculation prevented raising the rental cost, changing the terms, or canceling the contract except by the tenant himself, most of the tenants were not aware of the existence of the law that had not even been implemented in the first place.

Maya concludes by saying, “We are witnessing a real crisis today. The owners want to make profit in light of the crisis, and the tenants are selling their furniture just to be able to pay the month’s rent and not end up on the street. Sometimes they are forced to go as far as to stop sending their children to school in order to save money. Whereas the situation is even worse for foreign workers and displaced Syrians who avoid going to the justice system for help so that they would not be subjected to deportation, especially if their residency is illegal.”

Even in the case of those holding legal residency permits, the Lebanese judicial system was paralyzed last year and would not have been able to bring them any justice.

Being homeless is better than living with abuse

In 2013, Maryam (pseudonym), 52, decided to put an end to the violence that her husband had been inflicting upon her since she was 20 years old. She filed for divorce and left her son and daughter in their father’s house, becoming, as she herself puts it, “without a home”.

Maryam tells us that her agony began when “I opposed my father’s wishes and married a man from another faith. At that time, my family cut off relations with me for two years, until I gave birth to my son. The physical abuse had already started by then, and my ex-husband was careful not to leave traces of any beatings on my body, but over the years, he stopped caring and stopped being afraid, and the main reason is that my family was not supportive of me and therefore I had nowhere to go.”

Maryam could not leave the house until she was sure that she would not lose her son and daughter, who were aged 21 and 18 when she left. She explains, “Whenever I would ask him for a divorce, he would threaten to take my children away from me, and I would back down. When they grew up and were able to understand what was happening, they encouraged me to leave, and they gave me a safe place of residence in an apartment for girls (dorm room), in the Tariq El Jdideh area.”

Maryam stayed in the same shared residence until 2019, when the economic crisis began, and “my son lost his job and his sister was unable to pay the rent, which cost 600 thousand Lebanese pounds, and was equivalent to 300 US dollars at the time.” She adds, “At the time, the only option available to me was to seek refuge in my sister’s house, who lives with her husband.”

Unlike Samir, who considered himself homeless only when he lost every house that he could turn to, Maryam considers herself homeless ever since she lost her privacy. “I can’t even move around comfortably inside or outside the house, and I have to obey the laws set by my brother-in-law and sister,” she says, and adds, “To this day, my children have been suffering financially, and they are helping me by providing food and drink, which leaves me with no option but to keep quiet and abide by the rules set by my sister’s family.”

“I cannot go back to my father’s house, he won’t welcome me,” says Maryam. “And I certainly cannot go back to the house of my abusive ex-husband. Because I am not, and have never been, economically independent, my options are limited: I must either stay in my sister's house, live on the street, or go back to the abuse.”

Maryam hopes that her situation will improve soon so that she will be able to return to her own bed, especially since her son is currently trying to secure a residence for her and her daughter so that they can return and live “as a family under one roof”.

Feminist activist and executive director of the Fe-male NGO Hayat Mirshad notes that “many battered women do not know how to access the services available to them from organizations working in the field of protection against domestic violence.”

While Mirshad refers to the cultural normalization of violence, the greatest evil that remains “in the absence of the implementation of laws that protect women, in addition to the fact that many abused women are not financially independent and do not have a safe home to turn to.” As for the cases where a safe dwelling is provided by women’s organizations, “the process may sometimes take a long time.”

A homeless person living under one of Beirut’s bridges

Mirshad tells Raseef22, “In many cases, society blames women and holds them guilty for being subjected to domestic violence, and this guilt, along with the factors we have already mentioned, may prevent them from searching for a safe haven.” She adds that “there is also the pressure that’s exercised against her in the case there are children, since women are afraid of being deprived of having custody, or of even seeing them.”

Mirshad believes that the solution to giving women the choice between being homeless or living in an unsafe home, under the weight of violence, lies “in informing women of their rights and how they can benefit from the laws in force.” In return, she calls for more “pressure for the enforcement and application of the domestic violence law, and especially activating the financial fund established by law and its aim is to support women who have been subjected to violence.”

“Currently, in the absence of the government, only rights organizations are providing safe shelters for women” confirms Mirshad, further pointing out that “they are not capable of replacing the state, and this is what we witnessed during the COVID pandemic and lockdown, during which there was a significant increase in reported cases of domestic violence without there being any safe shelters available for women.”

رصيف22 منظمة غير ربحية. الأموال التي نجمعها من ناس رصيف، والتمويل المؤسسي، يذهبان مباشرةً إلى دعم عملنا الصحافي. نحن لا نحصل على تمويل من الشركات الكبرى، أو تمويل سياسي، ولا ننشر محتوى مدفوعاً.

لدعم صحافتنا المعنية بالشأن العام أولاً، ولتبقى صفحاتنا متاحةً لكل القرّاء، انقر هنا.