One question has haunted me since Israel resumed its genocidal war on Gaza: why are we dying?

Why does the blood of my people continue to spill across news screens? Why does a new mother cry for her lost children every day, why does a wife mourn her beloved live on air, and why does a “lone survivor” bid farewell to the departing ghost of his family with sorrow? Why are we still dying, as though it is our duty to die?

My family and I, my people, have the right to know why we are dying. We want just one reason for our death – so we can somehow endure it.

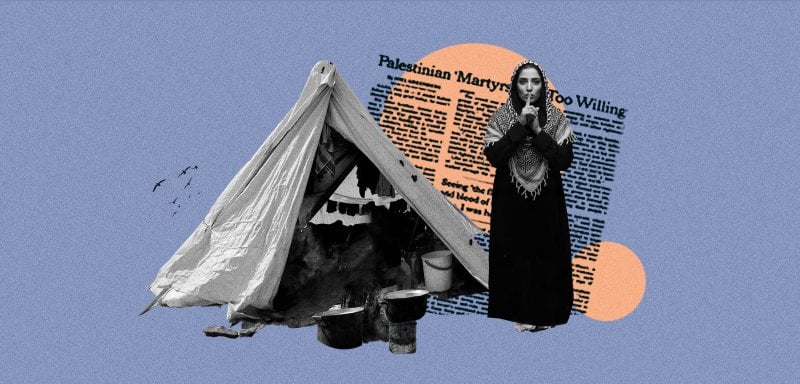

If it must happen, then let us at least know once and for all, before we go: why are we dying? For whom? On whose behalf? And in exchange for what? Will our deaths really result in a state? Or even a tent? If what our deaths will bring is a state, does it truly deserve all of this? And if it’s a tent, then can someone – anyone – please explain to me how any rational person would trade a house for a tent, and pay in blood to do so? Does a tattered tent deserve all this blood?

Why are we dying?

I might have been able to understand this death, if it were finite – if there had been a time limit, at least. For example, I could understand it if it were to end after a month, or two, or even two years, or when another 50,000 of us were killed. Its cruelty would still be immense, but maybe it would weigh a little less on those who are dying. Maybe people would say: “He wasn’t lucky. If he had been, he would’ve been one of the survivors.” And they wouldn’t say: “This is his fate,” or “he was destined to die.”

Is it written somewhere that my people are to die all at once and in such great numbers? Does this death mean that no one will ring the bell to end this massacre, and dismiss the remaining survivors from the classroom? That no referee will blow the whistle to signal the end of the slaughter?

Maybe we had to die so that our story could still be told – just as the world has become accustomed to it: always missing something – missing a death, a displacement, or a prison. I’ve never in my life met a Palestinian with a complete story.

If this must happen, then at the very least, my family and I, my people, have the right to know why we are dying. We want just one reason for our death – so we can somehow endure it.

Are we dying so the homeland may return? If so – what kind of homeland is it that feeds off a pool of blood? Have the rivers of blood that have flowed for 75 years ever restored a homeland? And if the homeland truly does return, after we’ve been killed, slaughtered, bombed, and burned – in our homes, in our tents, in our hospitals, in our streets – who will be left to live in this homeland?

Are we dying to win a round of war? If that’s the case, then defeat is better than a thousand victories.

He who has lost 50,000 of his children will never truly win. His defeat will haunt him forever. He’ll see it in his waking hours and in his dreams, in his long journey and in his brief rest, in his bombed-out house and while at work, in every visit to his favorite places – now turned deserts of blood and rubble.

So, our death neither restores a homeland, nor achieves victory. So, why are we dying, then?

Sometimes, I try to console myself by saying maybe we had to die so that our story could still be told – so that it would remain incomplete, just as the world has become accustomed to it: always missing something – missing a death, a displacement, a prison. I’ve never in my life met a Palestinian with a complete story. And so perhaps, we must die in the middle – before we get to know life well, before love and marriage, before we become doctors and engineers and entrepreneurs and thinkers, before giving birth to a little girl named Maryam. And before the idea of a homeland becomes complete in our minds – before it gives birth to sons and resisters.

Someone living in a tent doesn’t think about history. They think about how to make it through the long line for bread, how they will fill their empty jugs with water today. At night, they think about how to protect their children from the cold from outside and the fire from airstrikes. And in a moment of despair – or bombing – one question will cross their mind: why are we dying?

At other times, I wonder if this death of ours is nothing but a gamble. Like someone playing Russian Roulette in desperation, he stakes everything he owns: his money, his house, his children, even his future. Then he starts experiencing losses, bit by bit, but doesn’t stop. Those around him tell him to slow down, to turn back, to give up, to save what’s left. But he doesn’t stop – until he’s lost it all. Were we a losing bet in a game of roulette?

There’s no difference between a state and a tent

Don’t talk to me about patience, don’t tell me how Algeria sacrificed a million martyrs to liberate its land, and don’t mention how Vietnam defeated America. I don’t care what happened elsewhere in the world – I’m not thinking about that. Because someone living in a tent doesn’t think about history. They think about how to make it through the long line for bread, how they will fill their empty jugs with water today. At night, they think about how to protect their children from the cold from outside and the fire from airstrikes. And in a moment of despair – or bombing – one question will cross their mind: why are we dying?

Here, death doesn’t only mean physical extinction. Anyone who lives in a tent understands other meanings of death—ones that begin with blood and don’t end with hunger, thirst, or trembling. Those who lose their home and livelihood begin to understand additional meanings of death. And as for those who lose their entire family and become “the only survivor,” death becomes a constant companion.

Don’t talk to me about patience, and don’t look at my weakness, sadness, and tears over the rubble as “resilience.” They are of despair. I don’t want anything from you but a single answer — any answer — to the question: why all of this death? And if there is an end to it, what will this end be? And if it’s all going to lead to a state or to a tent, then there is no difference between the two banners.

Why don’t we just end the story?

I don’t care who wins and who loses. I don’t care whether victory signs are raised or lowered after the genocide. What matters to me is that the genocide ends. That, for once, we’d know why we are dying. That my people would stop dying every morning and every night. That they be given enough time to mourn their loved ones – those who were wrapped in plastic bags and departed this Earth with no funerals. Those whose bones were gathered from the streets and were buried missing a hand, or a foot, or a head – in mass graves.

Don’t talk to me about patience, and don’t look at my weakness, sadness, and tears over the rubble as “resilience.” They are of despair.

I don’t care about anything anymore. But I don’t want death to remain my people’s constant neighbor, for them to wake up and go to sleep seeing it. I don’t want a long time to pass before they can forget what happened – and I know they never will. Because who can forget that they were killed on Eid, while people outside were exchanging kisses and family visits?

Who can forget that while others were celebrating, they were hungry in their tent – or in their partially-bombed home? Who can forget that they died so many times, without ever knowing – just once – why they were dying? Why did they have to die?

Anyway, if we must die in the end, then why don’t we just die now – a final, eternal death – for the story to end? Let us no longer burden the world with our dying, or with our questions about what death is, and why it is happening so much to us. Or, let us be given one single chance to search for the graves of those we love, to stand before their remains in the soil, and try with all our might to find a single reason that could let them know: why did they die? why did they have to die? and why was there no other possible ending but their death?

Were their blood and bodies truly a lesson, an idea, or a path – or were they merely water, spilled into the river of history without anyone even looking back?

** The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Raseef22.

Raseef22 is a not for profit entity. Our focus is on quality journalism. Every contribution to the NasRaseef membership goes directly towards journalism production. We stand independent, not accepting corporate sponsorships, sponsored content or political funding.

Support our mission to keep Raseef22 available to all readers by clicking here!

Interested in writing with us? Check our pitch process here!